South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

RIGHT to COHABIT: a HUMAN RIGHT Sparsh Agarwal*And Abhiranjan Dixit**

© 2020 JETIR March 2020, Volume 7, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) RIGHT TO COHABIT: A HUMAN RIGHT Sparsh Agarwal*and Abhiranjan Dixit** * B.A.LL.B. (Hons.), 5th year, Law College Dehradun, **Assistant Professor, Law College Dehradun, Uttaranchal University. “WITH CHANGING SOCIAL NORMS OF LEGITIMACY IN EVERY SOCIETY INCLUDING OURS, WHAT WAS ILLEGITIMATE IN THE PAST, MAY BE LEGITIMATE TODAY.” ABSTRACT India is a country which is world known for its unique cultural diversity and cultural variation. This article works an attempt to sort out and find out why cohabitation have to face legal and cultural issues, even when, it is a right of every person to cohabit whether heterosexually or homosexually. It clears the idea that cohabitation is a human right and is nothing for which a separate demand is to be made. Human rights are natural rights and are vested into a person by Mother Nature and may not require a backbone of any statute. The article has been divided into seven major heads starting with Introduction to the topic which gives the statement of problem and object of the study. Further the article explains the concept of human rights and relationship of human rights with other existent rights. The article proceeds with the concept of cohabitation and legal provisions which support cohabitation in India. There are no any explicit provisions which legalize cohabitation but judicial interpretation is done in such a way that it has become legal and have been said to be human right of every person. Now, cohabitation is not only about living together of heterosexual people but also of homosexuals which is elaborated upon in the article. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

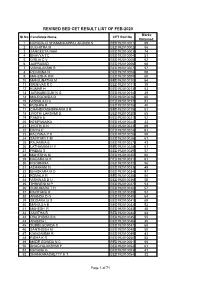

Revised Bed Cet Result List of Feb-2020

REVISED BED CET RESULT LIST OF FEB-2020 Marks Sl.No Candidate Name CET Roll No Obtained 1 NATARAJU SHANMUKAPPA LAKUNDI S BED192010001 59 2 SUCHITRA M BED192010002 56 3 SANGEETA NAIK BED192010003 74 4 BHAVYA TC BED192010004 51 5 GIRIJA C V BED192010005 62 6 JAIPRASAD BED192010006 68 7 VISHALAKSHI R BED192010007 57 8 REVANNA N BED192010008 68 9 MAHESHA M K BED192010009 60 10 MANJUNATHA M BED192010010 54 11 SRINIVAS R C BED192010011 39 12 KUMAR H BED192010013 53 13 JARINABEGUM N G BED192010014 39 14 MALEGOWDA D BED192010016 60 15 VISHALA D U BED192010017 51 16 PUSHPA R BED192010018 40 17 CHANDRASHEKHARA S E BED192010019 61 18 JYOTHI LAKSHMI D BED192010020 65 19 RAMYA N BED192010021 52 20 KEMPANAIKA BED192010022 33 21 JYOTHI B N BED192010023 69 22 DIVYA P BED192010024 61 23 KALPANA P R BED192010025 58 24 SAVITHRI T M BED192010026 61 25 RAJAMMA E BED192010027 43 26 LATHAMANI H V BED192010028 51 27 PREMA S BED192010029 57 28 MAHESHA M BED192010030 60 29 NAGARAJA K BED192010031 61 30 POORNIMA BED192010032 56 31 ASHARANI N BED192010033 49 32 BHASKARA M D BED192010034 97 33 KOMALA R BED192010035 50 34 VISHWAS D U BED192010036 58 35 THRIVENI M P BED192010037 53 36 SUKUMARA T H BED192010038 57 37 PAVITHRA R BED192010039 52 38 ANANDA D G BED192010040 64 39 SIDDARAJU S BED192010041 68 40 MANJULA B BED192010042 53 41 MAHESH R BED192010043 48 42 SAVITHA R BED192010044 64 43 PRATHIBHA B K BED192010045 55 44 ANANDA L BED192010046 45 45 SUBBEGOWDA S BED192010047 68 46 SANTHOSH M BED192010048 50 47 GANGAMMA R BED192010049 43 48 RISHA K R BED192010050 55 -

Courtesans in Colonial India Representations of British Power Through Understandings of Nautch-Girls, Devadasis, Tawa’Ifs, and Sex-Work, C

Courtesans in Colonial India Representations of British Power through Understandings of Nautch-Girls, Devadasis, Tawa’ifs, and Sex-Work, c. 1750-1883 by Grace E. S. Howard A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Grace E. S. Howard, May, 2019 ABSTRACT COURTESANS IN COLONIAL INDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF BRITISH POWER THROUGH UNDERSTANDINGS OF NAUTCH-GIRLS, DEVADASIS, TAWA’IF, AND SEX-WORK, C. 1750-1883 Grace E. S. Howard Advisors: University of Guelph Dr. Jesse Palsetia Dr. Norman Smith Dr. Kevin James British representations of courtesans, or nautch-girls, is an emerging area of study in relation to the impact of British imperialism on constructions of Indian womanhood. The nautch was a form of dance and entertainment, performed by courtesans, that originated in early Indian civilizations and was connected to various Hindu temples. Nautch performances and courtesans were a feature of early British experiences of India and, therefore, influenced British gendered representations of Indian women. My research explores the shifts in British perceptions of Indian women, and the impact this had on imperial discourses, from the mid-eighteenth through the late nineteenth centuries. Over the course of the colonial period examined in this research, the British increasingly imported their own social values and beliefs into India. British constructions of gender, ethnicity, and class in India altered ideas and ideals concerning appropriate behaviour, sexuality, sexual availability, and sex-specific gender roles in the subcontinent. This thesis explores the production of British lifestyles and imperial culture in India and the ways in which this influenced their representation of courtesans. -

6Th Entrance Examination -2020 Allotted List

6TH ENTRANCE EXAMINATION -2020 ALLOTTED LIST - 3rd ROUND 14/07/21 District:BAGALKOT School: 0266- SC/ST(T)( GEN) BAGALKOTE(PRATIBANVITA), BAGALKOTE Sl CET NO Candidate Name CET Rank ALLOT CATEG 1 FB339 PARWATI PATIL 131 GMF 2 FA149 PARVIN WATHARAD WATHARAD 13497 2BF 3 FM010 LAVANYA CHANDRAPPA CHALAVADI 17722 SCF 4 FP011 ISHWARI JALIHAL 3240 GMF 5 FM033 SANJANA DUNDAPPA BALLUR 3329 GMF 6 FK014 SHRUSTI KUMBAR 3510 GMF 7 FU200 BANDAVVA SHANKAR IRAPPANNAVAR 3646 GMF 8 FV062 SAHANA SHRISHAIL PATIL 3834 GMF 9 FM336 BIBIPATHIMA THASILDHAR THASILDHAR 4802 2BF 10 FD100 SUNITA LAMANI 53563 SCF 11 FH140 LAXMI PARASAPPA BISANAL 53809 STF 12 FL414 VARSHA VENKATESH GOUDAR 5510 3AF 13 FE285 RUKMINI CHENNADASAR 67399 SCF School: 0267- MDRS(H)( BC) KAVIRANNA, MUDHOL Sl CET NO Candidate Name CET Rank ALLOT CATEG 1 FM298 PRAJWALAGOUDA HALAGATTI 1039 GMM 2 FS510 VISHWAPRASAD VENKAPPA LAKSHANATTI 1109 GMM 3 FM328 LALBI WALIKAR 16027 2BF 4 FF038 SWATI BASAVARAJ PATIL 1743 GMF 5 FX194 RAHUL BAVALATTI 22527 STM 6 FL443 SHREELAKSHMI B KULAKARNI 2894 GMF 7 FR225 GEETAA SHIVAPPA KADAPATTI 3292 2AF 8 FU054 KAVYA DODDAVVA MERTI 53654 SCF 9 FT283 PUJA KOTTALAGI 64514 STF 10 FX248 SAMARTH SHIVANAND HALAGANI 883 GMM School: 0268- MDRS(U)( SC) MUCHAKHANDI, BAGALKOTE Sl CET NO Candidate Name CET Rank ALLOT CATEG 1 FE505 SHREEYAS SIDDAPPA GADDI 19156 STM 2 FP158 CHETAN LAMANI 33481 SCM 3 FB165 LOKESH V LAMANI 34878 SCM 4 FH101 PREM GANGARAM LAMANI 35697 SCM 5 FC321 SHRIKANTH BASAVARAJ LAMANI 35928 SCM 6 FD200 BHAGYASHREE SEETARAM LAMANI 54723 SCF 7 FE525 VAISHALI DHAKAPPA -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 15 March Final.Pdf

INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE 2015-2016 INDIA INTERNATIONAL CENTRE Board of Trustees Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, President Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna Prof. M.G.K. Menon Mr. Vipin Malik Dr. (Smt.) Kapila Vatsyayan Dr. R.K. Pachauri Mr. N.N. Vohra Executive Committee Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, Chairman Mr. K.N. Rai Air Marshal Naresh Verma (Retd.), Director Mr. Suhas Borker Cmde. Ravinder Datta, Secretary Smt. Shanta Sarbjeet Singh Mr. Dhirendra Swarup, Hony. Treasurer Dr. Surajit Mitra Mr. K. Raghunath Dr. U.D. Choubey Finance Committee Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna, Chairman Air Marshal Naresh Verma (Retd.), Director Dr. U.D. Choubey Cmde. Ravinder Datta, Secretary Mr. Rajarangamani Gopalan Mr. Ashok K. Chopra, CFO Mr. Dhirendra Swarup, Hony. Treasurer Medical Consultants Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. Mohammad Qasim Dr. Gita Prakash IIC Senior Staff Ms Omita Goyal, Chief Editor Ms Hema Gusain, Purchase Officer Dr. S. Majumdar, Chief Librarian Mr. Vijay Kumar Thukral, Executive Chef Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance & Accounts Officer Ms Premola Ghose, Chief, Programme Division Mr. Rajiv Mohan Mehta, Manager, Catering Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief, Maintenance Division Annual Report 2015–2016 This is the 55th Annual Report of the India International Centre for the year commencing 1 February 2015 to 31 January 2016. It will be placed before the 60th Annual General Body Meeting of the Centre, to be held on 31 March 2016. Elections to the Executive Committee and the Board of Trustees of the Centre for the two-year period, 2015–2017, were initiated in the latter half of 2014. -

Ujjwal Supa.Pdf

GramPanchayatName TownName Name FatherName Mothername CasteGroup AKHETI Akheti SARASWATHI ARUNA LOHARA TUKARAMA LOHARA ANANDI LOHARA OTHER AKHETI Karambal RAMAYI PANDURANGA GAVADA OTHER AKHETI Anamod PARVATHI MAHADEVA NAIK GOVINDA ANUSHA OTHER KALAMBULI(CASTLEROCK) Kalambuli SHRIMATHI MILAN SAHADEVA GONKAR BABALI MAHADEVA SAVANTHA GANGA BABALI SAVANTHA ST KALAMBULI(CASTLEROCK) Kalambuli ASHWINI PRAKASHA KAMBALE PRAKASHA BABU KAMBALE GEETHA PRAKASHA KAMBALE SC KALAMBULI(CASTLEROCK) Kalambuli SUMANA PRAKASHA KAMBALE PRAKASHA BABU KAMBALE GEETHA PRAKASHA KAMBALE SC KALAMBULI(CASTLEROCK) Kalambuli SONALI PRAKASHA KAMBALE PRAKASHA BABU KAMBALE GEETHA PRAKASHA KAMBALE SC KALAMBULI(CASTLEROCK) Kalambuli SUMANA PRAKASHA KAMBALE PRAKASHA BABU KAMBALE GEETHA PRAKASHA KAMBALE ST KALAMBULI(CASTLEROCK) Kalambuli SONALI PRAKASHA KAMBALE PRAKASHA BABU KAMBALE GEETHA PRAKASHA KAMBALE ST AKHETI Devulli(Tinai) DAKKI NAVALU GAVALIK BABU MALI OTHER AKHETI Devulli(Tinai) GODI BANU GAVALI BAIRU SAGGI OTHER AKHETI Devulli(Tinai) pinky n.g n.g d.g OTHER AKHETI Devulli(Tinai) SARASWATHI ATHMARAMA HANABARA RAMA SEETHA OTHER AKHETI Devulli(Tinai) PARVATHI SONI HANABARA SUBNA LAXMI OTHER ASU Chandawadi RADHIKA KRISHNA ANMODAKARA TUKARAM JEEJA OTHER ASU Chandawadi SHILPA KRISHNA ANMODAKARA KRISHNA NAGO ANMODAKARA RADHIKA KRISHNA ANMODAKARA OTHER ASU Chandawadi SHAILA KRISHNA ANMODAKARA KRISHNA NAGO ANMODAKARA RADHIKA KRISHNA ANMODAKARA OTHER ASU Chandawadi SUJATHA KRISHNA ANMODAKARA KRISHNA NAGO ANMODAKARA RADHIKA KRISHNA ANMODAKARA OTHER ASU Chandawadi SUPRIYA KRISHNA -

Admn. No.5422/2019 Office of the Prl. District & Sessions Judge, Hassan

Admn. No.5422/2019 Office of the Prl. District & Sessions Judge, Hassan, Dated: 20.11.2019 NOTIFICATION NO.01/2018, DATED:17.12.2018 QUALIFYING TEST INTIMATION LETTER The following applicants who have applied for the post of Typist- Copyist in Hassan unit in pursuance to the Notification No.01/2018, dated: 17.12.2018 are hereby directed to appear for the qualifying test at their own costs, in the SERIATE Manifold Solutions, (KEONICS Examination Center) VG complex, 1 st floor, 5 th cross, Shankarmatt road, KR Puram, Hassan from 11.12.2019 to 13.12.2019 . Further, the candidates are required to produce all the relevant original certificates/ documents regarding qualifications, category (if claimed), proof of date of birth, proof of identify (i.e., Aaadhar Card/ Driving License/Election ID etc.) and two character Certificates (general) (within six months) and another one character certificate issued by School authorities for verification and one set of xerox copies of documents with a passport size photo for verification before test. If the same is not produced, the candidature of the applicant is liable to be rejected and they shall not be allowed to take the qualifying test. They are also directed to bring the Hall ticket down loaded from the below mentioned website and produce the same to enter the examination hall. Website: https://districts.ecourts.gov.in/hassan-onlinerecruitment The candidates are required to transcript the dictated passage in Kannada and English on Computer. The candidates shall be present to the venue well in advance. The candidates coming late to venue after commencement of test will not be permitted to attend test. -

SEXUAL HEALTH and REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH RIGHTS in INDIA April 2018

Status of human rights in the context of SEXUAL HEALTH AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH RIGHTS IN INDIA April 2018 Country assessment undertaken for National Human Rights Commission by: Partners for Law in Development SAMA Resource Group for Women and Health Partners for Law in Development F-18, First Floor Jangpura Extension New Delhi- 110014 Tel.: 011- 24316832/41823764 pldindia.org cedawsouthasia.org SAMA Resource Group for Women and Health B-45, Second Floor Shivalik Main Road Malviya Nagar New Delhi – 110017 Tel: 011-26692730/65637632 samawomenshealth.in FINAL REPORT CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................... 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 13 Sexual health and well-being ........................................................................................................ 13 Reproductive health and rights ..................................................................................................... 15 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 17 PART I COUNTRY ASSESSMENT ON HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE CONTEXT OF SEXUAL HEALTH AND WELL-BEING .................................................................................................................................... -

Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-24-2015 12:00 AM "More or Less" Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema Sarbani Banerjee The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Prof. Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Sarbani Banerjee 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sarbani, ""More or Less" Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3125. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3125 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i “MORE OR LESS” REFUGEE? : BENGAL PARTITION IN LITERATURE AND CINEMA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Sarbani Banerjee Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Sarbani Banerjee 2015 ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I problematize the dominance of East Bengali bhadralok immigrant’s memory in the context of literary-cultural discourses on the Partition of Bengal (1947). -

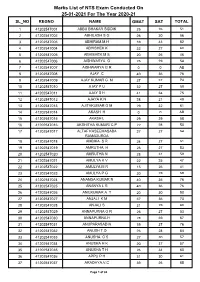

Marks List of NTS Exam Conducted on 25-01-2021 for the Year 2020-21 SL NO REGNO NAME GMAT SAT TOTAL

Marks List of NTS Exam Conducted On 25-01-2021 For The Year 2020-21 SL_NO REGNO NAME GMAT SAT TOTAL 1 41202547001 ABBU BHAKAR SIDDIK 25 26 51 2 41202547002 ABHILASH S G 26 30 56 3 41202547003 ABHIRAM.M.H 39 43 82 4 41202547004 ABHISHEK K 33 27 60 5 41202547005 ABHISHEK M S 20 26 46 6 41202547006 AISHWARYA G 25 29 54 7 41202547007 AISHWARYA G R 0 0 AB 8 41202547008 AJAY C 40 36 76 9 41202547009 AJAY KUMAR G M 37 37 74 10 41202547010 AJAY P U 32 27 59 11 41202547011 AJAY S H 41 34 75 12 41202547012 AJAYA K N 28 21 49 13 41202547013 AJITHKUMAR G M 29 32 61 14 41202547014 AKASH H 0 0 AB 15 41202547015 AKASH L 29 29 58 16 41202547016 AKSHITHA KUMARI C P 22 28 50 17 41202547017 ALTAF KASEEMASABA 27 27 54 RAMADURGA 18 41202547018 AMBIKA S R 24 27 51 19 41202547019 AMRUTHA H 26 27 53 20 41202547020 AMRUTHA N 28 31 59 21 41202547021 AMULYA K V 22 25 47 22 41202547022 AMULYA M R 15 26 41 23 41202547023 AMULYA P G 30 29 59 24 41202547024 ANANDA KUMAR R 40 36 76 25 41202547025 ANANYA L R 40 36 76 26 41202547026 ANILKUMAR A T 20 30 50 27 41202547027 ANJALI K M 37 36 73 28 41202547028 ANJALI S 31 29 60 29 41202547029 ANNAPURNA G R 26 27 53 30 41202547030 ANNAPURNA H 28 39 67 31 41202547031 ANUPARASAD N 39 37 76 32 41202547032 ANUSH T.D 26 28 54 33 41202547033 ANUSHA C S 27 30 57 34 41202547034 ANUSHA H K 20 37 57 35 41202547035 ANUSHA T H 26 34 60 36 41202547036 APPU P H 31 30 61 37 41202547037 ARADHYA.V.C 39 26 65 Page 1 of 82 Marks List of NTS Exam Conducted On 25-01-2021 For The Year 2020-21 SL_NO REGNO NAME GMAT SAT TOTAL 38 41202547038 ARBASKHAN