Case Study: Distington Big Local, Cumbria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distington Parish Plan 2005

Voluntary Action Cumbria DISTINGTON CP Distington Parish Council Distington Parish Development and Action Plan 2005-2010 Prepared by Distington Parish Council The Parish Of Distington The Parish of Distington is situated four miles from Workington and Whitehaven, and ten miles from Cockermouth, and is made up of the villages of Distington, Gilgarran and Pica plus the surrounding area. The population of 2247, recorded in the 2001 census, shows a decrease of 270 on the 1995 figures which was already down 107 on the 1991 figure, making a total reduction of 377 or 10.3% in just 10yrs. This is a trend, which may have turned around since 2001, as the housing association now report that there is a waiting list for housing in the Parish. In the past, the Parish was largely dependent upon farming, coal mining, iron making and High Duty Alloys for its income. All of these industries have declined over the years. There is now no coal mining or iron making, and High Duty Alloys and farming are much reduced in the number they employ. Most of the Community now has to travel to the neighbouring towns and further a field for employment, which is made difficult for some by the scarcity of public transport, especially for those who cannot drive, and in particular the school leaver. The 1995 census showed that of the 972 households in the Parish 295 did not own a car, which is 34% a reduction of 4% on the 1995 figure of 38%. The census also showed that 19% of the residents were over 65, with a further 27% over the age of 45, statistics which many believe will have increased considerably over recent years, meaning that there will be a greater need for better public transport, and a greater demand for recreational activities. -

Copeland Unclassified Roads - Published January 2021

Copeland Unclassified Roads - Published January 2021 • The list has been prepared using the available information from records compiled by the County Council and is correct to the best of our knowledge. It does not, however, constitute a definitive statement as to the status of any particular highway. • This is not a comprehensive list of the entire highway network in Cumbria although the majority of streets are included for information purposes. • The extent of the highway maintainable at public expense is not available on the list and can only be determined through the search process. • The List of Streets is a live record and is constantly being amended and updated. We update and republish it every 3 months. • Like many rural authorities, where some highways have no name at all, we usually record our information using a road numbering reference system. Street descriptors will be added to the list during the updating process along with any other missing information. • The list does not contain Recorded Public Rights of Way as shown on Cumbria County Council’s 1976 Definitive Map, nor does it contain streets that are privately maintained. • The list is property of Cumbria County Council and is only available to the public for viewing purposes and must not be copied or distributed. -

Applications Received by Copeland Borough Council for Period

Applications Received by Copeland Borough Council for period Week ending 3 July 2020 App No. 4/20/2232/0F1 Date Received 29/06/2020 Proposal SINGLE STOREY REAR EXTENSION Case Officer Chloe Unsworth Site 3 WINDSOR COURT, WHITEHAVEN Parish Whitehaven Applicant E Graham Address 3 Windsor Court, WHITEHAVEN, Cumbria CA28 6UU Agent Address App No. 4/20/2233/0F1 Date Received 29/06/2020 Proposal ERECTION OF PORCH TO FRONT OF PROPERTY Case Officer Chloe Unsworth Site 13 SCREEL VIEW, PARTON, WHITEHAVEN Parish Parton Applicant Mr Geoffrey Brown Address 13 Screel View, Parton, WHITEHAVEN, Cumbria CA28 6NH Agent Address App No. 4/20/2234/0F1 Date Received 29/06/2020 Proposal ERECT BEDROOM, STUDY AND DINER EXTENSIONS Case Officer Chloe Unsworth Site BURNEY, THE GREEN, MILLOM Parish Millom Without Applicant Mr Sam Moore Address Burney, The Green, MILLOM, Cumbria LA18 5JB Agent Mr A Walker Address Rockland, Lady Hall, MILLOM, Cumbria LA18 5HR Applications Received by Copeland Borough Council for period Week ending 3 July 2020 App No. 4/20/2235/0F1 Date Received 30/06/2020 Proposal TWO STOREY SIDE EXTENSION TO PROVIDE A GARAGE AT GROUND FLOOR LEVEL AND BEDROOM Case Officer Sarah Papaleo AND BATHROOM AT FIRST FLOOR LEVEL Site 4 KEEKLE COTTAGES, CLEATOR MOOR Parish Weddicar Applicant Mr G Kennedy Address 4 Keekle Cottages, CLEATOR MOOR, Cumbria CA25 5RG Agent Calva Design Studio Address 2 Calva House, Calva Brow, WORKINGTON, Cumbria CA14 1DE, FAO Mr Richard Lindsay App No. 4/20/2238/TPO Date Received 02/07/2020 Proposal CROWN LIFTING OF A SYCAMORE TREE SITUATED WITHIN A CONSERVATION AREA Case Officer Chloe Unsworth Site 3 CORKICKLE, WHITEHAVEN Parish Whitehaven Applicant K P Arborists Address Hollydene, Harras Moor, WHITEHAVEN, Cumbria CA28 6SG, FAO Mr Paul Cottier Agent Address App No. -

THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION for ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW of COPELAND Final Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in T

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF COPELAND Final recommendations for ward boundaries in the borough of Copeland August 2018 DISTINGTON, LOWCA & PARTON Sheet 1 of 1 LOWCA CP DISTINGTON CP Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. PARTON CP This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. MORESBY The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2018. CP N LAMPLUGH N E ARLECDON AND CP V L A A MORESBY FRIZINGTON CP H R E T T I N G H E KEY TO PARISH WARDS W C D HILLCREST LOWSIDE QUARTER CP S O E WEDDICAR L H L CP A BRAYSTONES E K F B NETHERTOWN WHITEHAVEN L CP I WEDDICAR CP CORKICKLE M C KEEKLE SNECKYEAT D WEDDICAR NORTH C WHITEHAVEN K SOUTH J WHITEHAVEN CP ARLECDON & P MOOR ROW ENNERDALE E CORKICKLE NORTH & BIGRIGG F CORKICKLE SOUTH CLEATOR MOOR CP G HARRAS H HILLCREST I KELLS CLEATOR MOOR J MIREHOUSE EAST K MIREHOUSE WEST L SNECKYEAT NORTH M SNECKYEAT SOUTH ENNERDALE AND N WHITEHAVEN CENTRAL NORTH KINNISIDE CP O WHITEHAVEN CENTRAL SOUTH P WHITEHAVEN SOUTH ST. BEES CP EGREMONT CP ST BEES EGREMONT HAILE CP B LOWSIDE QUARTER CP BECKERMET WASDALE CP PONSONBY A CP BECKERMET CP GOSFORTH GOSFORTH & SEASCALE CP SEASCALE CP ESKDALE CP IRTON WITH SANTON CP DRIGG AND CARLETON CP ULPHA MUNCASTER CP CP BLACK COMBE & SCAFELL WABERTHWAITE CP BOOTLE CP MILLOM WITHOUT CP WHICHAM CP 01 2 4 MILLOM Kilometres MILLOM 1 cm = 0.4340 km CP KEY BOROUGH COUNCIL BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PARISH BOUNDARY PROPOSED WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH PROPOSED PARISH WARD BOUNDARY CORKICKLE PROPOSED WARD NAME SEASCALE CP PARISH NAME. -

Howgate/ Distington Partnership Community Plan 2012

Page 1 of 23 Howgate/ Distington Partnership Community Plan 2012 1 Introduction 1.1 In the early part of 2001, a steering group was formed from members of the three parishes who make up the old county council division of Howgate. The parishes are Lowca Moresby and Parton. The group worked with Voluntary Action Cumbria, now known as Action with Communities in Cumbria (ACT), under the Countryside Agency Vital Villages programme and received grant aid from that body. The result was the Howgate Ward Plan published in 2003. 1.2 In 2004, the Parish Council at Distington took a decision to produce what they described as a Development and Action Plan. A group was formed which met on a monthly basis through 2004. In addition to parish councillors, the local Vicar, the head teacher of the Distington Community School and the leader of the club for young people in Distington were members of the group. In 2005 they published this plan to cover the period 2005 to 2010. They were assisted by ACT and grant aid was obtained from the Vital Villages fund. 1.3 Both documents can be viewed and downloaded from the ACT website (www.cumbriaaction.org.uk) following the links to Community Plans. 1.4 The plan can also be viewed on the Copeland Borough Council website (www.copeland.gov.uk) following the links from Community and Living and on both the Moresby Parish Council (www.moresbypc.org.uk) and Parton Parish Council (www.partonpc.co.uk) websites 06 August 2012 Page 2 of 23 2 Progress of the Groups 2.1 The Howgate Steering Group resolved to meet on a quarterly basis to progress matters included in the Action Plan and to produce a newsletter. -

Board Meeting Minutes 13-02-2019

Distington Big Local Distington Community Centre, Church Road, Distington CA14 5TE Distington Big Local Ltd /Partnership Board Meeting 13 February 2019, 1pm Distington Community Centre Present: Rhoda Robinson (Chair), Julia Powley, Norma Pritt, Josephine Greggain, Alison Boyd, Annette Whitehead, Karen Hodgson, Sue Hunter, Paul Tharagonnet, Margaret Hildrop, Alan Hunter, Pete Duncan, Ingrid Morris (Minutes), Lindsay Bodman, Ronnie Hewer Apologies: Vic Askew, Elaine Ismay, Shelley Hewitson 149.19 Welcome The chair welcomed everybody. 150.19 Conflict of Interests Alan Hunter, Board nomination 151.19 Minutes of Previous Meeting Were passed as a true record 152.19 Land Development The meeting started with a presentation from housing consultant Damian Southworth. He talked us through the financial side of our proposal, alternative costings, tenures, delivery options and practical next steps to ensure that our project is viable. We are in the process of getting the access road to land (from Church Rd) either transferred to us or passed to Cumbria County Council Highways for adoption through a Section 38 Agreement. We are also hoping for the freehold of the access road to be transferred to us which will enable us to get a Section 106 agreement in place with United Utilities to access the main drains on Church Road. Dodd & Co are working on getting charitable status for DBL Ltd and looking at the tax implications of transferring the land to a new company. Our final grant payment from Copeland Community Fund of £2,610 to help pay for the Feasibility Study and Community Consultation will hopefully be received soon. Home England are still carrying out their ‘due diligence’ checks. -

Applications Received by Copeland Borough Council for Period

Applications Received by Copeland Borough Council for period Week ending 23 February 2018 App No. 4/18/2078/0F1 Date Received 19/02/2018 Proposal CHANGE OF USE FROM FORMER BANK TO HOT FOOD TAKEAWAY Case Officer Christie M Burns Site 29 MARKET PLACE, EGREMONT Parish Egremont Applicant Cemal Altun Address 29 Market Place, EGREMONT, Cumbria CA22 2WY Agent Day Cummins Architects Address Unit 4 Lakeland Business Park, Lamplugh Road, COCKERMOUTH, Cumbria CA13 0QT, FAO Mr Michael Dawson App No. 4/18/2079/0F1 Date Received 19/02/2018 Proposal PERMANENT RETENTION OF A 46.75m LONG PALISADE FENCE Case Officer Christie M Burns Site NEWTON MANOR, GOSFORTH Parish Gosforth Applicant NDA Properties Ltd Address c/o agent Agent GVA Address Norfolk House, 7 Norfolk Street, MANCHESTER M2 1DW, FAO Miss Alice Routledge App No. 4/18/2080/0F1 Date Received 20/02/2018 Proposal PRIOR NOTIFICATION OF PROPOSED DEMOLITION OF A TWO WING TIMBER FRAMED MODULAR Case Officer Heather Morrison BUILDING Site SELLAFIELD SITE, SEASCALE Parish Beckermet with Thornhill Applicant Sellafield Limited Address Sellafield, SEASCALE, Cumbria CA20 1PG, FAO Mr P Foster Agent Sellafield Limited Address Sellafield, SEASCALE, Cumbria CA20 1PG, FAO Mr David Harris Applications Received by Copeland Borough Council for period Week ending 23 February 2018 App No. 4/18/2081/0E1 Date Received 20/02/2018 Proposal LAWFUL DEVELOPMENT CERTIFICATE FOR PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT - DORMER TO REAR Case Officer Christie M Burns Site 10 MOOR TERRACE, MILLOM Parish Millom Applicant Mr J Wearing Address 10 Moor Terrace, MILLOM, Cumbria LA18 5EN Agent M&P Gadsden Consulting Engineers Address 20 Meetings Industrial Estate, Park Road, BARROW IN FURNESS, Cumbria LA14 4TL App No. -

070019 02 First Issue

Commercial in Confidence Executive Summary As part of the National Air Quality Strategy (NAQS), local authorities are required to undertake a Progress Report of air quality in their areas in years when they are not carrying out their three yearly Updating and Screening Assessment or carrying out a Detailed Assessment. The 2006 Updating and Screening Assessment and the 2007 Progress Report both concluded that it was unlikely that the air quality objectives for any of the seven pollutants would be exceeded within Copeland Borough. The results of the current pollutant monitoring programme within Copeland are presented in this report and are compared with previous years. The current pollutant monitoring programme, using diffusion tubes, began in the spring of 2000 at numerous locations throughout Copeland. The pollutants monitored were nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulphur dioxide (SO2), benzene (C6H6) and ozone (O3). If the current monitoring campaign highlights areas of elevated concentrations of any of these pollutants, it may be advisable to consider more detailed monitoring in these areas. Ozone was also monitored due to a lack of emission source data and monitoring data in Copeland. Ozone is assessed at a national level, rather than by local authorities, with the UK having to meet the requirements of the 2nd Daughter Directive by 31st December 2005. The results of the air quality monitoring programme in the Borough of Copeland show that, in general, the concentrations of three of the four pollutants monitored are below the NAQS objectives (NO2, SO2 and benzene). It is therefore considered that these three pollutants are present in concentrations at which adverse health effects are either not observed or, in the case of benzene, represent a very small risk to health. -

West Cumbria: Opportunities and Challenges 2019 a Community Needs Report Commissioned by Sellafield Ltd

West Cumbria: Opportunities and Challenges 2019 A community needs report commissioned by Sellafield Ltd February 2019 2 WEST CUMBRIA – OPPORTUNITIES & CHALLENGES Contents Introduction 3 Summary 4 A Place of Opportunity 6 West Cumbria in Profile 8 Growing Up in West Cumbria 10 Living & Working in West Cumbria 18 Ageing in West Cumbria 25 Housing & Homelessness 28 Fuel Poverty 30 Debt 32 Transport & Access to Services 34 Healthy Living 36 Safe Communities 42 Strong Communities 43 The Future 44 How Businesses Can Get Involved 45 About Cumbria Community Foundation 46 WEST CUMBRIA – OPPORTUNITIES & CHALLENGES 3 Introduction Commissioned by Sellafield Ltd and prepared by Cumbria Community Foundation, this report looks at the opportunities and challenges facing communities in West Cumbria. It provides a summary of the social needs and community issues, highlights some of the work already being done to address disadvantage and identifies opportunities for social impact investors to target their efforts and help our communities to thrive. It is an independent report produced by Cumbria We’ve looked at the evidence base for West Community Foundation and a companion document Cumbria and the issues emerging from the statistics to Sellafield Ltd’s Social Impact Strategy (2018)1. under key themes. Our evidence has been drawn from many sources, using the most up-to-date, Cumbria Community Foundation has significant readily available statistics. It should be noted that knowledge of the needs of West Cumbria and a long agencies employ various collection methodologies history of providing support to address social issues and datasets are available for different timeframes. in the area. -

Allerdale Borough Council

APPENDIX A Consultation on proposals for care services in Allerdale and Distington areas November 2011 – February 2012 Report by Fran Branfield & Jenny Willis On behalf of Cumbria County Council Consultation report on proposals for care services in Allerdale and Distington areas 1 Contents Page Acknowledgements 3 Overall Summary 4 1. Introduction and background 6 2. Responses to public questionnaire 9 3. Conversations with residents 42 4. Responses by letter and email 56 Park Lodge 57 Richmond Park 69 Woodlands 74 General letters 77 5. Public Meetings 80 6. Drop in session feedback 90 7. Staff views 100 Appendix 1: Copies of full responses from: Age UK 106 Alzheimer’s UK 108 Copeland Borough Council 113 Allerdale Borough Council 115 Cumbria LINKS 121 122 Adult Social Care comments on LINk response to consultation 148 Appendix 2: Petitions about Park Lodge and Richmond Park 161 Appendix 3: Public questionnaire 162 Appendix 4: Public meeting/drop in questionnaires 167 Consultation report on proposals for care services in Allerdale and Distington areas 2 Acknowledgements We would like to thank all the residents of the homes we visited who shared their thoughts about where they live and on the Councils plans for their future, as well as relatives, staff and members of the public who took the time to contribute to the consultation. Consultation report on proposals for care services in Allerdale and Distington areas 3 Overall summary This report by Cairn Community Partnerships is based on the views and opinions of people living in the Allerdale and Distington areas of West Cumbria. This includes present residents of three Cumbria Care homes which have been proposed for closure in the consultation document, Park lodge (Aspatria), Richmond Park (Workington) and Woodlands (Distington); the voices of relatives and friends and of other community stakeholders, as well as staff and people attending ‘drop-ins’ and public meetings run by the Council. -

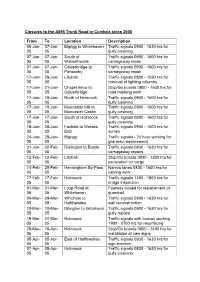

05 07-Jan- 05 Bigrigg to Whitehaven T

Closures to the A595 Trunk Road in Cumbria since 2005 From To Location Description 06-Jan- 07-Jan- Bigrigg to Whitehaven Traffic signals 0900 - 1630 hrs for 05 05 gully cleaning 07-Jan- 07-Jan- South of Traffic signals 0900 - 1600 hrs for 05 05 Waberthwaite carriageway repair 07-Jan- 07-Jan- Calderbridge to Traffic signals 0900 - 1600 hrs for 05 05 Ponsonby carriageway repair 17-Jan- 28-Jan- Lillyhall Traffic signals 0800 - 1530 hrs for 05 05 removal of lighting columns 17-Jan- 21-Jan- Chapel Brow to Stop/Go boards 0800 - 1530 hrs for 05 05 Calderbridge road marking work 17-Jan- 18-Jan- North of Holmrook Traffic signals 0900 - 1600 hrs for 05 05 gully cleaning 17-Jan- 18-Jan- Muncaster Mill to Traffic signals 0900 - 1600 hrs for 05 05 Muncaster Castle gully cleaning 17-Jan- 17-Jan- South of Holmrook Traffic signals 0900 - 1600 hrs for 05 05 gully cleaning 18-Jan- 28-Jan- Foxfield to Wreaks Traffic signals 0900 - 1600 hrs for 05 05 End survey 24-Jan- 28-Jan- Bigrigg Traffic signals - 24 hour working for 05 05 gas main replacement 31-Jan- 02-Feb- Distington to Bootle Traffic signals 0830 - 1630 hrs for 05 05 carriageway repairs 12-Feb- 12-Feb- Lillyhall Stop/Go boards 0830 - 1200 hrs for 05 05 excavation on verge 14-Feb- 25-Feb- Hensingham By-Pass Narrow lanes 0800 - 1600 hrs for 05 05 cabling work 17-Feb- 17-Feb- Holmrook Traffic signals 1300 - 1800 hrs for 05 05 bridge inspection 01-Mar- 31-Mar- Loop Road at Footway closed for replacement of 05 05 Whitehaven guardrail 09-Mar- 09-Mar- Whicham to Traffic signals 0900 - 1630 hrs for 05 05 -

Copeland Area Plan 2012-14 Cumbria County Council

Cumbria County Council Copeland Area Plan 2012-14 Cumbria County Council Cumbria County Council - Serving the people of Copeland What we have done in Copeland The County Council has: • Invested over £250,000 in grants across the area; • Put £57,000 in to fund a Money Advice service in Copeland; • Invested an additional £10,000 to trial an extended Money Advice outreach service, installing five remote kiosks for people in rural parts of the district; • Spent over £16,000 in 2011-12 to support the ongoing work of local credit unions in Copeland; • Managed the Intensive Start Up Support (ISUS) programme providing advice and guidance to new businesses, resulting in 67 new starts and 77 jobs in Copeland in 2011/12; • Supported the development of social enterprises including providing 13 business assists to the sector in West Cumbria; • Promoted the inward investment opportunities available in West Cumbria, as well as supporting a number of manufacturing companies through the aftercare programme resulting in two more international companies in the nuclear and related field in 2011 being attracted to Westlakes Science Park; • Assisted 57, 18-24 year olds in Copeland and Allerdale into work for a minimum of 6 months. The council assisted 102 long term incapacity benefit claimants in West Cumbria into jobs and 110 into training through the Return to Work programme in 2010. Our priorities for Copeland • Improve the local economy; • Tackle inequalities in relation to poverty and health needs; • Improve transport connections; • Deliver customer focused