Arctic Research Collaborations Among Agencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arctic!Sea!Ice!

! ! ! ! Study!of!Environmental!Arctic!Change!(SEARCH)! Knowledge!Exchange!Workshop!on!the!Impacts!of!Arctic!Sea!Ice!Loss! September(14+15,(2016( Arctic(Research(Consortium(of(the(U.S.((ARCUS)(DC(Office/( Consortium(for(Ocean(Leadership,(1201(New(York(Avenue,(Washington,(DC(20005( ( Summary! ( Effective(responses(to(diminishing(Arctic(sea(ice(require(effective(communication(as(well(as( collaborative(and(actionable(science.(In(this(workshop,(scientific(experts,(decision+makers,( Arctic(residents,(industry(specialists,(NGO's,(and(other(stakeholders(will(define(and(address( important(societal(questions(raised(by(diminishing(Arctic(sea(ice,(and(explore(new( approaches(and(partnerships(for(advancing(awareness(and(understanding(of(the(associated( impacts.(( ( This(workshop(is(an(activity(of(the(Study!of!Environmental!Arctic!Change!(SEARCH)!Sea! Ice!Action!Team((SIAT;(https://www.arcus.org/search+program/sea+ice),(which(is( developing(a(coherent(source(of(accessible,(comprehensive,(and(timely(information( that(synthesizes(the(connections(between(the(science(of(Arctic(sea(ice(loss,(key(societal( issues,(and(stakeholder(needs.(( ( Agenda!! ! Wednesday,!Sept!14! 8:00–8:30(AM( Arrival((Light(refreshments(&(coffee(provided)( 8:30–8:50(AM(( Welcome(and(Introductions(–"SIAT"Leadership"&"Bob"Rich,"ARCUS( 8:50+9:05( ( Overview(of(the(Study(of(Environmental(Arctic(Change((SEARCH)( –(Brendan"Kelly,"SEARCH( 9:05–9:20(AM(( Overview(of(the(SEARCH(Sea(Ice(Action(Team’s(mission(to(foster( collaborative(science,(community(engagement,(and(effective( communication(( -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

Charter Constitutionalism: the Myth of Edward Coke and the Virginia Charter*

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers 7-2016 Charter Constitutionalism: The yM th of Edward Coke and the Virginia Charter Mary Sarah Bilder Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Legal History Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Mary Sarah Bilder. "Charter Constitutionalism: The yM th of Edward Coke and the Virginia Charter." North Carolina Law Review 94, no.5 (2016): 1545-1598. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 94 N.C. L. REV. 1545 (2016) CHARTER CONSTITUTIONALISM: THE MYTH OF EDWARD COKE AND THE VIRGINIA CHARTER* MARY SARAH BILDER** [A]ll and every the persons being our subjects . and every of their children, which shall happen to be born within . the said several colonies . shall have and enjoy all liberties, franchises and immunities . as if they had been abiding and born, within this our realm of England . .—Virginia Charter (1606)1 Magna Carta’s connection to the American constitutional tradition has been traced to Edward Coke’s insertion of English liberties in the 1606 Virginia Charter. This account curiously turns out to be unsupported by direct evidence. This Article recounts an alternative history of the origins of English liberties in American constitutionalism. -

Norse America

BULLFROG FILMS PRESENTS NORSE AMERICA Study Guide by Thomas H. McGovern NORSE AMERICA 56 minutes Produced & Directed by T.W. Timreck and W.N. Goetzmann in association with the Arctic Studies Center at Smithsonian Institution VHS videos and DVDs available for rental or purchase from Bullfrog Films® ©1997 Bullfrog Films, Inc. Guide may be copied for educational purposes only. Not for resale. NORSE AMERICA Study Guide by Thomas H. McGovern North Atlantic Biocultural Organization Anthropology Department Hunter College, CUNY 695 Park Ave., New York, N.Y. 10021 SYNOPSIS Norse America introduces the viewer to the latest findings on the Viking-Age voyages across the North Atlantic to North America. It places these medieval transatlantic travels in the wider context of prehistoric maritime adaptations in North Atlantic Europe, and illustrates the continuity of seafaring traditions from Neolithic to early medieval times. The remarkable Norse voyages across the North Atlantic were part of the Scandinavian expansion between AD 750-1000 that saw Viking raids on major European monasteries and cities, long distance trading ventures into central Asia, and the settlement of the offshore islands of the North Atlantic. The impact of Viking raiders on the centers of early medieval literacy are comparatively well-documented in monastic annals and contemporary histories, but the Norse movement westwards into the Atlantic is recorded mainly by modern archaeology and by the semi-fictional sagas produced by the Norsemen themselves. While many of the sagas describe events of the 9th and 10th centuries (complete with memorable dialog and very specific descriptions of scenery), they werefirst written down in the 13th-14th centuries in Iceland. -

Facts and Myths About Misperceptions Brendan Nyhan Brendan Nyhan Is Professor of Government, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New

Facts and Myths about Misperceptions Brendan Nyhan Brendan Nyhan is Professor of Government, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. His email is [email protected]. Abstract Misperceptions threaten to warp mass opinion and public policy on controversial issues in politics, science, and health. What explains the prevalence and persistence of these false and unsupported beliefs, which seem to be genuinely held by many people? Though limits on cognitive resources and attention play an important role, many of the most destructive misperceptions arise in domains where individuals have weak incentives to hold accurate beliefs and strong directional motivations to endorse beliefs that are consistent with a group identity such as partisanship. These tendencies are often exploited by elites, who frequently create and amplify misperceptions to influence elections and public policy. Though evidence is lacking for claims of a “post-truth” era, changes in the speed with which false information travels and the extent to which it can find receptive audiences require new approaches to counter misinformation. Reducing the propagation and influence of false claims will require further efforts to inoculate people in advance of exposure (e.g., media literacy), debunk false claims that are already salient or widespread (e.g., fact-checking), reduce the prevalence of low- quality information (e.g., changing social media algorithms), and discourage elites from promoting false information (e.g., strengthening reputational sanctions). On August 7, 2009, former vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin reshaped the debate over the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act when she published a Facebook post falsely claiming that “my parents or my baby with Down Syndrome will have to stand in front of [Barack] Obama’s ‘death panel’ so his bureaucrats can decide.. -

Summer 2014 E G D I R B M a C

The James Caird Society Newsletter Issue 20 · Summer 2014 e g d i r b m a C f o y t i s r e v i n U , e t u t i t s n I h c r a e s e R r a l o P t t o c S f o y s e t r u o C . y e l r u H k n a r F y b e r u t c i P Bi-weekly ablutions of The Ritz . Wordie, Cheetham and Macklin scrubbing the floor So many celebrations, so much to be done... 2014 marks the centenary of the start of the Endurance tributes will take many different forms, but all are united Expedition. Like the expedition itself, an enormous by a common theme, namely that of honouring the amount of hard work and preparation has gone, and remarkable feats of discovery in the Antarctic and continues to go, into the celebration of this momentous commending the qualities of leadership associated with Sir anniversary. Expeditions, dinners, boat restorations, Ernest. Before you turn the page to read more about what theatrical productions, publications – events galore are is planned for the anniversary, spare a thought for all those planned in honour of Sir Ernest Shackleton and the other who will be working tirelessly behind the scenes to make members of his team whose achievements will never be sure that everything for the Centenary celebrations is forgotten. As you will see in the following pages, these shipshape! Registered Charity No. -

Nauigatio Sancti Brendani 'The Voyage of Brendan'

Nauigatio Sancti Brendani ‘The Voyage of Brendan’: Landscape and Paradise in Early Medieval Ireland Dr Elva Johnston (UCD School of History & Archives) I. Introduction to the Nauigatio Nauigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis, the Voyage of St Brendan the Abbot, is one of the most famous of all early medieval Irish texts.1 It is a Hiberno-Latin narrative which was probably written in Ireland by the second half of the eighth century (Dumville 1998) or during the ninth (Esposito 1961; Carney 1963). It describes how St Brendan, a sixth- century early Irish abbot, is called to go on a journey to the Promised Land of the Saints which, the text tells us, can be found in the Atlantic Ocean to the west of Ireland. He is accompanied by a crew of monks on a voyage lasting seven years. The travellers must pass various tests before reaching their goal. Brendan visits islands in the north Atlantic, encounters monks, celebrates Easter on the back of a giant sea creature and meets Judas Iscariot. After reaching the Promised Land of the Saints, Brendan and the remaining monks return home. The text draws on a rich literary heritage which may stretch back into the early seventh century (Carney 1963). It is widely believed in popular culture that it describes an actual voyage to the Americas, undertaken by early medieval Irish monks (Ashe 1962; Severin 1978). Most scholars, however, interpret it as a symbolic religious text which should not be read literally (Bourgeault 1983; O’Loughlin 1999; O’Loughlin 2005). This paper will highlight the different landscapes described in the Nauigatio, exploring how they provide the tale with interpretative depth. -

Brendan Reilly [email protected] College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences T: 1-201-315-1866 Oregon State University Last Update: March 12, 2019

Brendan Reilly [email protected] College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences T: 1-201-315-1866 Oregon State University Last update: March 12, 2019 EDUCATION Oregon State University, College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences Ph.D. Ocean, Earth, and Atmospheric Sciences (Geology & Geophysics), June 2018 Thesis: Deciphering Quaternary geomagnetic, glacial, and depositional histories using paleomagnetism in tandem with other chronostratigraphic and sedimentological approaches Graduate Certificate in College and University Teaching, December 2016 Advisor: Joseph Stoner Montclair State University, Department of Earth and Environmental Studies M.S. Geoscience, May 2013 Thesis: Climate evolution of the Antarctic Peninsula over the last 1,000 years: An environmental magnetism analysis of two high resolution sediment cores Advisor: Stefanie Brachfeld Boston College, Carroll School of Management B.S. Management (Marketing), Environmental Studies Minor received May 2008, Magna Cum Laude RELEVENT EXPERIENCE 2019 (start Dec. 1) Institutional Postdoc, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego Topic of Focus: Southern Ocean paleomagnetic stratigraphy and Antarctic glacial history 2018-2019 Research Associate (Postdoc), Oregon State University Topic of Focus: Arctic and Subarctic Sediment Paleosecular Variation 2013-2018 Research Assistant, Oregon State University Topic of Focus: Sediment Magnetism and Non-Destructive Analysis of Arctic, North American, and Indian Ocean Holocene – Quaternary Sediments 2014-2015 Teaching -

Researching North America: Sir Humphrey Gilbert's 1583

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History History, Department of 5-2013 Researching North America: Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s 1583 Expedition and a Reexamination of Early Modern English Colonization in the North Atlantic World Nathan Probasco University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the European History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the United States History Commons Probasco, Nathan, "Researching North America: Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s 1583 Expedition and a Reexamination of Early Modern English Colonization in the North Atlantic World" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 56. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Researching North America: Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s 1583 Expedition and a Reexamination of Early Modern English Colonization in the North Atlantic World by Nathan J. Probasco A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Carole B. Levin Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2013 Researching North America: Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s 1583 Expedition and a Reexamination of Early Modern English Colonization in the North Atlantic World Nathan J. Probasco, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Advisor: Carole B. -

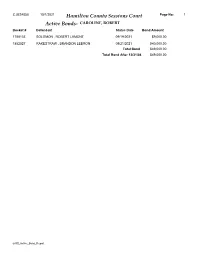

Active Bonds- CAROLINE, ROBERT Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount

CJUS4058 10/1/2021 Hamilton County Sessions Court Page No: 1 Active Bonds- CAROLINE, ROBERT Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount 1788133 SOLOMON , ROBERT LAMONT 09/19/2021 $9,000.00 1852527 RAKESTRAW , BRANDON LEBRON 09/21/2021 $40,000.00 Total Bond $49,000.00 Total Bond After 12/31/04 $49,000.00 arGS_Active_Bond_Report CJUS4058 10/1/2021 Hamilton County Sessions Court Page No: 2 Active Bonds- A BONDING COMPANY Docket # Defendant Status Date Bond Amount 1768727 LEE , KAITLIN M 06/30/2019 $12,500.00 1792502 WAY , JASON J 01/11/2020 $3,000.00 1796727 FERRY , MATTHEW BRIAN 02/21/2020 $2,500.00 1804712 VILLANUEVA , ADAM LOUIS 05/25/2020 $3,000.00 1809034 SINFUEGO , NARCIAN LYNET 07/12/2020 $2,000.00 1817402 PETER , DALE NEIL 08/14/2021 $0.00 1830111 HAZLETON , SAMUEL T 02/14/2021 $2,000.00 1830122 HILL , JARED LEVI 02/14/2021 $500.00 1831701 TEAGUE , PAMELA KAYE 03/01/2021 $5,000.00 1831702 TEAGUE , PAMELA KAYE 03/01/2021 $2,000.00 1835471 SHROPSHIRE , EDWARD LEBRON 04/06/2021 $1,500.00 1839064 CHESNUTT , ALAN ARNOLD 05/06/2021 $2,500.00 1839968 SAARINEN , NICHOLAS AARRE 05/15/2021 $1,500.00 1844159 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $3,000.00 1844160 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $2,000.00 1844161 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $0.00 1844162 WATSON , JONATHAN M 06/26/2021 $0.00 1846317 SMALL II, AARON CLAY 07/20/2021 $2,000.00 1846876 GIARDINA , MICHAEL N 07/24/2021 $3,000.00 1847003 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $1,500.00 1847004 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $1,000.00 1847006 SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK 07/26/2021 $500.00 1847417 -

Some Landmarks in Icelandic Cartography Down to the End of The

ARCTIC VOL. 37, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 198-4) P. 389-401 Some Landmarks in.keland-ic. Cartography down to the End of the Sixteenth Century HARALDUR. SIGURDSSON* Sometime between 350.and 310 B.C., it is thought, a Greek Adam of Bremen,and Sax0 ,Grammaticus both considered navigator, F‘ytheas of Massilia .(Marseilles), after a sail of six Iceland and Thule to be the same country. Adam is quite ex- daysfrom the British Isles, came to anunknown country plicit on the point:“This Thule is now named Iceland from the which hemmed Thule. The sources relating.to this voyageare ice which bind the sea” (von .Bremen, 1917:IV:36; Olrik and fragmentary and less explicit than one might wish. ‘The infor- Raeder, 1931:7). When the ,Icelanders themselves.began to mationis taken from its original contextand distorted in write about their country (Benediktsson, 1968:31) they were various ways. No one knows what country it wasthat F‘ytheas quite certain that Iceland was the same country as that which came upon farthest from his native shore, and most of the the Venerable Bede called by the name of Thule. .North Atlantic countries have been designated as .candidates. Oldest among .the maps on which Iceland is shown is the But in the.form in which it has come downto us, Pytheas’sac- Anglo-Saxon map, believed to have been made somewhere count does not, in reality, fit ,any of them. His voyage ‘will around the year 1OOO. If that dating is approximatelyright, this always remain one of the insoluble riddles of geographical is the first knownOccurrence in writing of the name history. -

St Brendan the Navigator

St Brendan the Navigator By Daniel Sullivan Maps from the time of Columbus, included a small island called St. Brendan’s Isle that existed somewhere west of Europe. It was also mentioned in a Latin text dating from the 9th Century titles Navigation Santi Brendani Abatis (Voyage of St. Brendan the Abbot) It describes the voyage as having taken place in the 6th Century. Several copies of this text have survived in monasteries in Europe. It was an important folk lore in medieval Europe and may have influenced Columbus. Historians relate that Brendan was born about 484 A.D. near Tralee Co Kerry in Ireland. He was ordained by Bishop Erc and sailed about northwest Europe, spreading the Christian faith and founding monasteries, the largest at Clonfert, Co. Galway where he was buried in 577 A.D. at the age of 93. The account of Brendan’s voyage contained a detailed description of the construction of his boat which was not unlike currachs still made today. Skeptics could not accept that such a small vessel could possibly sail in the open sea let alone accomplish such a voyage. Several passages in the legend also seemed incredible. They were raised up on the back of sea monsters, they passed crystals that rose up to the sky and were pelted with flaming foul smelling rocka by the inhabitants of a large island on their route. They finally arrived at a beautiful land they called the Promised Land of the Saints. They explored till they came to a great river that divided the land.