A Momentous Leap in Handgun Power Occurred with the Advent of the .44 Magnum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dick” Casull (Part 2 of 2) by John S

Newsletter of the Utah Gun Collectors Association February 2014 PLEASE HELP! UGCA desperately needs someone to be Treasurer! The current treasurer has a great system of records in place, mostly automated using Quick Books, so this involves recording and report- ing ongoing operations, not start- ing something from scratch. If you have some Quick Books or basic accounting skills, PLEASE contact Nick at 801-495-xxxx for details on this important job. Like all UGCA leadership jobs, this is an unpaid volunteer job. March Show with March 8-9, 2014 Ruger Collectors again... The Ruger Collectors have asked to be included in our March show. We look forward to them returning with their great displays. It is always fun to see what “the other guys collect” just in case you are getting tired of BEST your current collecting interest. UTAH SHOW! Is that old gun loaded? A surprising number ARE loaded! Don’t trust those muzzle loaders! At the January show, a visitor brought in a muzzle loading swivel barrel pistol, which was sold to a member. Although our security folks do a great job with cartridge arms, it is a bit harder to check muzzle loaders. UGCA Board of Directors This one had Officers BOTH barrels President Gary N. loaded, even Vice President Jimmy C. though there Treasurer Nick W. were no caps on Secretary Linda E. the nipples. ALWAYS run a Directors 2013-2014 rod down the Jimmy C. barrel and make Gary N. sure it reaches Gaylord S. all the way to Don W. Nick W. the breech! Two powder charges and bulles from “unloaded gun.” Watch those tubular magazine guns! Directors 2014–2015 Jim D. -

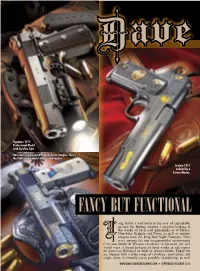

Fancy but Functional BBQ Guns!

the Handguns of Dave signature 1911 professional Model with sureFire light. dave does regular work with the texas rangers. Here’s the professional model with custom touches. custom 1911 ordered by a former Marine. Fancy But Functional BBQ Guns! ong before I had much in the way of expendable income for buying sixguns I enjoyed looking at the works of such past gunsmiths as O’Meara, Houchins, Sedgely and Eimer as well as custom L sixguns from the King Gun Sight Company. They were among the top sixgunsmiths customizing Colt and Smith & Wesson revolvers in between the two world wars. I found pictures of their works in old copies of American Rifleman as well as several books. Today we are blessed with a wide range of revolvers, semi-autos, and single shots in virtually every possible chambering, as well 52 WWW.AMERICANHANDGUNNER.COM • SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 Lauck a blued, retro-1911 made for a client who wanted a 95 percent retro-look, but also built to be “shooter” he could use in pike-style matches. dave’s handy with single actions too! John taFFin Fancy But Functional BBQ Guns! Photos: chuck Pittman, inc. d &l’s centennial model, serial no. 101, for the 101st as being offered in not only the traditional blued steel but year of the 1911. stainless steel, polymers, titanium, scandium and possibly even un-obtainium. Our choices are almost endless; in fact so much so one might think there would be no need for custom sixgunsmiths today — but think again. The greatest pistolsmiths who ever lived are practicing their creative art right alongside all the factory offerings. -

Gun Digest 6-Shooter Special Revolver Compilation Download

Think the Colt 1873 Single Action Army won the West? Think again! When Bulldogs Ruled olt, Remington, Smith & Wesson and Merwin & Hulbert didn’t manufacture them, but during the late nineteenth century they were Camong the Old West’s most well-known pocket revolvers. Though the second “…a small, short-barrel pistol of large caliber…” the genuine British Bulldog nineteenth century-produced, double- action, stubby short-barreled revolvers chambered for medium to large calibers.” At the end of the Civil War, many ex-soldiers, civilians, and city folk took their chances on a new life in the yet unsettled and lawless areas of the Amer- ican West. Those who dared the long trek prepared themselves with every- thing from general supplies to reliable These future Westerners were a sophisti- cated lot when it came to choosing their the 1870s, many Western townships This close-up of a Belgian-made British were beehives of activity, chock-full of many had to conceal their arms to Bulldog (maker unknown) shows the gold-seekers, gamblers, homesteaders, circumvent the restriction. By 1875, both quality of the simple engraving pattern and other opportunists. The market was the Midwest and the California coast common to these imported revolvers. ripe for a small size, large-caliber revolver that was concealable but powerful enough for a armed dispute. Most of all, the revolver had to be affordable in price. Though Remington brought out a number of pocket revolvers to include a double action by 1870, as well as Smith & Wesson’s Baby Russian, a competitor from abroad surprised U.S. -

Accurate Arms Company, Inc

Smokeless Powders LOADING GUIDE Number Two ® iii DISCLAIMER Accurate Arms Company, Inc. disclaims all possible liability for damages, including actual, incidental and consequential, result- ing from reader usage of information or advice contained in this book. Use data and advice at your own risk and with caution. Copyright © 2000 by Accurate Arms Company, Inc. ACCURATE ARMS COMPANY, INC. 5891 Highway 230 West McEwen, Tennessee 37101 Designed and Printed by: Wolfe Publishing Company 6471 Airpark Drive, Prescott, AZ 86301 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following individuals contributed to the preparation of this loading guide: Doyle Nunnery Joe White Lane Pearce Randy Brooks Allan Jones Randy Craft Bob Palmer J.D. Jones Jay Postman Tom Griffin Kevin Thomas Carroll Pilant Mike Wright Ken French Dave Scovill The following companies have been helpful in the preparation of this loading guide: Action Arms Barnes Bullets Blount Industries Bull-X Bullets Clements Casting C. Sharps Arms CP Bullets Cooper Arms Douglas Barrels Eldorado Cartridge Freedom Arms Hornady Bullets HS Precision Lee Precision Lyman Products Magnum Research Miller Arms McGowan Barrels Nosler Bullets Penn's Casting Penny's Casting Precision Machine Remington Arms Company Redding-SAECO Sierra Bullets Speer Bullets Sinter Fire, Inc. Starline Thompson/Center Arms Ultra Light Arms White Rock Tool & Die Bill Wiseman Wolfe Publishing Company v LEGEND AF A-Frame N/R No Recommendation BAR Barnes OAL Overall Length BRG Berger PART Nosler Partition BT Ballistic Tip PMC PMC/Eldorado Cartridge CCI CCI, Division of Blount PSPCL Pointed Softpoint Core Lokt FA Freedom Arms RAN Ranier Bullet Co. FC Federal Cartridge REM Remington FIO Fiocchi RN Roundnose FMJ Full Metal Jacket RPM Rock Pistol Manufacturing FN Flatnose S1000 Solo 1000 FP Flat Point S1250 Solo 1250 FPJ Flatpoint Jacket S&W Smith & Wesson FS Fail Safe SAAMI Sporting Arms and Ammunition GC Gas Check Manufacturers' Institute, Inc. -

Gun Digest 2010 Revolver Compilation Download

Think the Colt 1873 Single Action Army won the West? Think again! When Bulldogs Ruled ÅÅ Å olt, Remington, Smith & Wesson and Merwin & Hulbert didn’t manufacture them, but during the late nineteenth century they were Camong the Old West’s most well-known pocket revolvers. Though the second definition of “bulldog” in Webster’s is “…a small, short-barrel pistol of large caliber…” the genuine British Bulldog may further be defined as “any of the nineteenth century-produced, double- action, stubby short-barreled revolvers chambered for medium to large calibers.” At the end of the Civil War, many ex-soldiers, civilians, and city folk took their chances on a new life in the yet unsettled and lawless areas of the Amer- ican West. Those who dared the long trek prepared themselves with every- thing from general supplies to reliable firearms for hunting and self-defense. These future Westerners were a sophisti- cated lot when it came to choosing their rifles, pistols and shotguns, and did so according to their financial means. By the 1870s, many Western townships forbade carrying firearms openly, thus This close-up of a Belgian-made British were beehives of activity, chock-full of many had to conceal their arms to Bulldog (maker unknown) shows the gold-seekers, gamblers, homesteaders, circumvent the restriction. By 1875, both quality of the simple engraving pattern and other opportunists. The market was the Midwest and the California coast common to these imported revolvers. ripe for a small size, large-caliber revolver that was concealable but powerful enough for a serious gunfight or other armed dispute. -

Gun Notes: a Common Sense Look at Handgun Hunting by John Linebaugh

Gun Notes: A Common Sense Look at Handgun Hunting by John Linebaugh My first sixgun was an old 3-screw .357 Ruger Blackhawk, 6 1/2" bbl. I shot this for about 1 year and then traded it to my brother and bought an identical gun 4 5/8" length. I was about 15 or 16 then and considered myself somewhat of a sixgunner. In my native state of Missouri I probably was. But in the eyes of real sixgunners I was plenty wet behind the ears. I read everything I could in the magazines about shooting and game shooting. To take a deer with a sixgun seemed an enormous task, one requiring exceptional skill and ability. I did not feel I was up to it. I continued to pack a sixgun for the years to come but never put it to use on anything bigger than rabbits and a few treed coon. In 1976 I moved to Wyoming and was fortunate enough to meet two gentlemen who had over the several previous years taken nearly 100 head of big game between them - with sixguns! From what they taught and showed me I began to plan for some "sixgun only" hunts. I had reams of material, and each "expert" had his idea and method. However, none of them seemed to fit comfortable on me. Many used the short, underpowered rifles but I wasn’t fooled by that approach. I was too deeply engrained with theories of Elmer Keith. I had a .44 Mag Super Blackhawk but planned to use a gun of equal power but with less noise and recoil. -

Handgun Roster Board

The following is a list of handguns manufactured after January 1, 1985 that have received final approval by the Handgun Roster Board. HANDGUN ROSTER January 2020 Rachel Rosenberg Handgun Roster Board Administrator Maryland State Police PREFACE Be advised that the Handgun Roster is a live, electronic document and that this publication represents only those firearms that appeared on the roster as of January 2, 2020. Current roster listings can be found on the Licensing Division’s portal of the Maryland State Police, https://licensingportal.mdsp.maryland.gov/MSPBridgeClient/#/home. Questions regarding this publication or the roster as it appears on the portal can be directed to the Handgun Roster Board Administrator, Ms. Rachel Rosenberg. Ms. Rachel Rosenberg Handgun Roster Board Administrator 1201 Reisterstown Road Baltimore, MD 21208 410-653-4247 Maryland Department of State Police Official Handgun Roster July 1, 2020 Make (Importer) Model Model Number Caliber Accuracy X, Inc. Frame N/A 9 mm, 38 Spl, 40 S&W, 45 ACP, 10 mm Adler (Chiappa Firearms) 301 Honcho N/A 410 Gauge, 20 Gauge, 12 Gauge Advanced Armament MPW 102869 300 BLK Advanced Weapon Systems (AWS) Trench 12 N/A 12 Gauge Agrozet National CZ -83 N/A 380 ACP AKAI Custom Guns, LLC 1911 & 2011 Frame 9mm, 40 S&W, 45 ACP, 10mm Alchemy Arms Spectre N/A 9 mm, 40 S&W, 45 ACP Alchemy Custom Weaponry Anomaly N/A 45 ACP Adler (Chiappa Firearms) 301 Honcho N/A 410 Gauge Aldo Uberti & Co. 1851 Richards Conversion N/A 38 Spl, 38 Colt, 44 Colt Aldo Uberti & Co.