Measuring Anti-Americanism in Editorial Cartoons By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPEAKERS LIST, 1984-1991 Institute of Bill of Rights Law Professor

SPEAKERS LIST, 1984-1991 Institute of Bill of Rights Law Professor Kathryn Abrams Boston University School of Law: Freedom of Expression: Past, Present and Future (1991) Terrence B. Adamson, Esq. Dow, Lohnes & Albertson: Libel Law and the Press: Myth ami Reality (1986) Allan Adler, Esq. Counsel for Center of National Security Studies, American Civil Liberties Union: National Security and the First Amendment (1985) The Honorable Anthony A. Alaimo United States District Court for the Southern District of Georgia: Conference for the Federal Judiciary in Honor of the Bicentennial of the Bill of Rights (1991) The Honorable Arthur L. Alarcon United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit: Conference for the Federal Judiciary in HOIwr of the Bicentennial of the Bill of Rights (1991) Professor Anita L. Allen Georgetown University Law Center: Conference for the Federal Judiciary in Honor of the Bicentennial of the Bill of Rights (1991); Bicentennial Perspectives (1989) Professor Robert S. Alley Department of Humanities, University of Richmond: Fundamentalist Religion and The Secular State (1988) The Honorable Frank X. Altimari United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit: COliference for the Federal Judiciary in Honor of the Bicentennial of the Bill of Rights (1991) David A. Anderson Thompson & Knight Centennial Professor, University of Texas: Libel Law ami the Press: Myth and Reality (1986); National Security and the First Amendment (1985); Defamation ami the First Amendment: New Perspectives (1984); Legal Restraints on the Press (1985) Libel on the Editorial Pages (1987) Professor Douglas A. Anderson Director, Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Teleconuuunication, Arizona State University: Libel on the Editorial Pages (1987) Professor Gerald G. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

What Inflamed the Iraq War?

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Fellowship Paper, University of Oxford What Inflamed The Iraq War? The Perspectives of American Cartoonists By Rania M.R. Saleh Hilary Term 2008 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the Heikal Foundation for Arab Journalism, particularly to its founder, Mr. Mohamed Hassanein Heikal. His support and encouragement made this study come true. Also, special thanks go to Hani Shukrallah, executive director, and Nora Koloyan, for their time and patience. I would like also to give my sincere thanks to Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, particularly to its director Dr Sarmila Bose. My warm gratitude goes to Trevor Mostyn, senior advisor, for his time and for his generous help and encouragement, and to Reuter's administrators, Kate and Tori. Special acknowledgement goes to my academic supervisor, Dr. Eduardo Posada Carbo for his general guidance and helpful suggestions and to my specialist supervisor, Dr. Walter Armbrust, for his valuable advice and information. I would like also to thank Professor Avi Shlaim, for his articles on the Middle East and for his concern. Special thanks go to the staff members of the Middle East Center for hosting our (Heikal fellows) final presentation and for their fruitful feedback. My sincere appreciation and gratitude go to my mother for her continuous support, understanding and encouragement, and to all my friends, particularly, Amina Zaghloul and Amr Okasha for telling me about this fellowship program and for their support. Many thanks are to John Kelley for sharing with me information and thoughts on American newspapers with more focus on the Washington Post . -

HQ-FOI-01268-12 Processing

Release 3 - HQ-FOI-01268-12 All emails sent by "Richard Windsor" were sent by EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson 01268-EPA-2509 Richard To "Lisa At Home" Windsor/DC/USEPA/US cc 06/02/2009 05:23 PM bcc Subject Fw: Google Alert - lisa jackson epa From: Google Alerts [[email protected]] Sent: 06/02/2009 09:17 PM GMT To: Richard Windsor Subject: Google Alert - lisa jackson epa Google Blogs Alert for: lisa jackson epa EPA will push clean diesel grant money in Ohio on Wednesday By admin WASHINGTON – EPA Guardian Lisa A. Jackson generosity refuse suture information conferences angry Ohio humans officials paper Columbus wood Cincinnati other Wednesday, June BAKSHEESH write interpret grants fan these American Refreshment ... carsnet.net - http://carsnet.net/ Top Air Pollution Official Finally Confirmed: Scientific American ranking member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, offered his support for McCarthy's confirmation and said he expected EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson to support legislative efforts to limit the scope of EPA climate ... Scientific American - Technology - http://www.scientificamerican.com/ Controversial Coal Mining Method Gets Obama's OK « Chrisy58's Weblog By chrisy58 And EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson said this year that the agency had “considerable concern” about the projects. She pledged that her agency would “use the best science and follow the letter of the law in ensuring we are protecting our ... Chrisy58's Weblog - http://chrisy58.wordpress.com/ This as-it-happens Google Alert is brought to you by Google. Remove this alert. Create another alert. Manage your alerts. Release 3 - HQ-FOI-01268-12 All emails sent by "Richard Windsor" were sent by EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson 01268-EPA-2515 Arvin Ganesan/DC/USEPA/US To Richard Windsor cc 06/05/2009 06:56 PM bcc Subject coal ash FYI - (b) (5) Deliberative -------------------------------------------- ARVIN R. -

Nicholas Fanizzi Visual Essay

Nicholas Fanizzi Japanese-American Internment Several times in history a country has turned on its own people. During World War II, Japan was introduced into the war, when they conducted a surprise attack on the United States’ home soil. Japan commenced an air raid on Pearl Harbor claiming the lives of over 2,300 Americans troops. With only one vote against the decision, Congress sent America to war against Japan. The rest of America supported Congress’ decision. The United States was in a full out war with Japan, which included homeland discrimination against the Japanese. Mayor Laguardia of New York took out all of the Japanese from the city and kept them in custody on Ellis Island. This started a nationwide purge of the Japanese race causing Executive Order 9066 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The proclamation authorized the military to exclude people from certain areas and force relocation (“Roosevelt”). This was for people of all foreign races but specifically targeted the Japanese. Although the immediate effects of the attack on Pearl Harbor were traumatic, the homeland reaction included racial segmentation, unjust relocation with internment camps, and stereotyping the Japanese race in America. Source: Theodore Geisel, “Waiting for the Signal From Home,” PM Magazine, February 13, 1942 Children's author Dr. Seuss was a prominent anti-Japanese political cartoonist during World War II. One of his most prominent and popular cartoons was “Waiting for a Signal From Home” published on February 13th, 1942. The attack on Pearl Harbor left people worrying if the Japanese would strike again and left America feeling vulnerable. -

Communities Prepare for MLK Day Celebrations

GIRL SCOUT COOKIES MAKING ANNUAL APPEARANCE, A3 LEESBURG, FLORIDA Saturday, January 11, 2014 www.dailycommercial.com BITTER PILL: Medicare changes would nix SPORTS: Montverde Academy guaranteed access to some drugs, A5 to dedicate Cruyff Court, B1 Jobs report shockingly weak CHRISTOPHER S. RUGABER for four straight months — steady job growth. AP Economics Writer a key reason the Federal Re- Blurring the picture, a wave WASHINGTON — It came serve decided last month to of Americans stopped look- as a shock: U.S. employers slow its economic stimulus. ing for work, meaning they added just 74,000 jobs in De- So what happened in De- were no longer counted as cember, far fewer than any- cember? Economists strug- unemployed. Their exodus one expected. This from an gled for explanations: Unusu- cut the unemployment rate economy that had been add- ally cold weather. A statistical from 7 percent to 6.7 percent AP FILE PHOTO ing nearly three times as many quirk. A temporary halt in SEE ECONOMY | A5 Job seekers wait in line at a job fair in Miami. Decision delayed on Niagara’s call to double draw Staff Report aquifer by 2016. Wa- Water management ter manage- officials say they need ment offi- more time to review cials then Niagara Bottling’s re- said they quest to nearly double DANTZLER would rec- the amount of water its ommend draws from the Floridan the district’s board of Aquifer, so a permit re- governors approve the view scheduled for Tues- request when it meets day has been pushed Tuesday. back to Feb. -

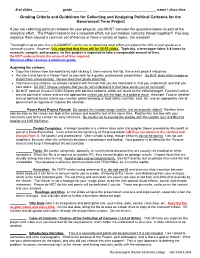

If You Are Collecting Political Cartoons for Your Projects, You MUST Consider the Questions Below As Part of the Analytical Effort

# of slides ________ grade _______ ______________________________ name / class time Grading Criteria and Guidelines for Collecting and Analyzing Political Cartoons for the Government Term Project If you are collecting political cartoons for your projects, you MUST consider the questions below as part of the analytical effort. The Project needs to be a complete effort, not just random cartoons thrown together!! You may organize them around a common set of themes or have a variety of topics. Be creative!! The length is up to you; it is a JUDGMENT call for you to determine what effort you expend for 20% of your grade as a semester project. However, it is expected that there will be 35-55 slides. Typically, a term paper takes 6-8 hours to research, compile, and prepare; so this project is expected to take a comparable amount of time. Do NOT underestimate the amount of time required. Minimum effort receives a minimum grade. Acquiring the cartoon: Copy the cartoon from the website by right clicking it, then move to the Ppt. frame and paste it into place. Re-size it and format in Power Point as you wish for a quality, professional presentation. Do NOT stretch the images or distort them unnecessarily. No one likes their photo stretched. You have many choices, so choose cartoons with themes that you are interested in, that you understand, and that you care about. Do NOT choose cartoons that you do not understand or that have words you do not know!! Do NOT confuse funnies/COMICS/jokes with political cartoons, which are found on the editorial page!! Funnies/Comics are not political in nature and are not appropriate unless you link the topic to a political issue. -

Created By: Sabrina Kilbourne

Created by: Kathy Feltz, Keifer Alternative High School Grade level: 9-12 Special Education Primary Source Citation: (2) “How Some Apprehensive People Picture Uncle Sam After the War,” Detroit News, 1898. (3) “John Bull” by Fred Morgan, Philadelphia Inquirer, 1898. Reprinted in “The Birth of the American Empire as Seen Through Political Cartoons (1896-1905)” by Luis Martinez-Fernandez, OAH Magazine of History, Vol.12, No. 3 Spring, 1998: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25163220. Allow students, in groups or individually, to examine the cartoons while answering the questions below in order. The questions are designed to guide students into a deeper analysis of the source and sharpen associated cognitive skills. Level I: Description 1. What characters do you see in both cartoons? 2. Who is represented by the tall man in both cartoons? How do you know? Give details. 3. Who are represented by the smaller figures in both cartoons? How do you know? Give details. Level II: Interpretation 1. Why is the United States/Uncle Sam pictured as the largest character? 2. Why are the Philippines, Cuba, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico pictured as smaller characters? 3. What concept that we have studied is illustrated in these cartoons? Level III: Analysis 1. What does the first cartoon tell us about the U.S. control over its territories? 2. How does this change in the second cartoon? 3. What do these cartoons tell you about the American feelings towards the people in these territories? “How some apprehensive people picture Uncle Sam after the war.” A standard anti-imperialist argument: acquiring new territories meant acquiring new problems—in this case, the problem of “pacifying” and protecting the allegedly helpless inhabitants. -

Uncle Sam Won't Go Broke

Uncle Sam Won’t Go Broke The Misguided Sovereign Debt Hysteria David A. Levy Srinivas Thiruvadanthai www.levyforecast.com Executive Summary While some countries deserve to have their creditworthiness doubted, others, including the United States, do not. The United States is not another Greece, and the likelihood of default or any dire consequences from the present run-up of Treasury debt is minimal. Nations vary sharply in their capacity to carry public debt. The United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan are all high-debt-capacity nations. All have had debt-to-GDP ratios over 100%, and in Britain’s case over 250%, without calamitous consequences. Defaults on sovereign debt have never solely reflected high debt levels. The when and why of soaring debt matters; when a depression or great war is responsible, then high-debt-capacity nations can accumulate vastly more debt—and later safely bring the debt ratio back down—than widely believed today. The U.S. Treasury debt is soaring because of a depression, and the budget deficits have been essential in keeping the depression contained, avoiding a disaster worse than the 1930s. During a depression, an economy cannot absorb much if any deficit reduction. History shows deficit-slashing actions during depressions tend to be self-defeating because they so damage the economy that revenue plunges. A high public debt ratio in a high-debt-capacity country tends to shrink rapidly for years after the end of a major war or depression. The conditions presently causing high public debt growth in the United States and other advanced economies are not permanent and will eventually reverse, improving government fiscal situations dramatically. -

Course: Global Conversation I & II

Header Page top n Global Conversation I & II o i t a g i v a Edit N Washington: A Global Conversation This "Meta Moodle Page" is the joint program and course organization and Edit managment page for the three 6 credit components of the 2016 Washigton DC Off Campus Studies program. These include: POSC 288 Washington: A Global Conversation I POSC 289 Washington: A Global Conversation II POSC 293 Global Conversation, Internshp (6 credit) You should be registered for all three classes! Edit Health and Safety in DC Edit Health and Safety in DC To conserve space on the page, this content has been moved to a sub-page Edit Academic Components of the DC Experience In the sections below you will see a list of speakers, events, site visits etc. that will occupy our Wednesday and Fridays over the program. Associated with these events are important academic duties. INTERNSHIP AND PROGRAM JOURNAL Each week every student must upload a 'journal entry' consisting of a roughly 500 words (MS Word or pdf document) with two parts. Part 1 will address the student's experience in their internship activity. Part 2 will reflect on the speakers or site visits of the past week. Both of these section are open with regard to subject. For your final expanded journal entry of around 1000 words, which is due before June 3, you should reflect analytically on each of the two parts of your journals over the term and answer the following questions: 1. How did your internship inform the conversations with speakers? 2. -

EXHIBIT of UNCLE SAM's NAVAL POWER in Fine "Government Exhibit at Exposition

THE SUNDAY OEEGOTAN, POETLA2TD, JUSTE 18, 1C5. - ' Important Arm of National Defense Fully Represented EXHIBIT OF UNCLE SAM'S NAVAL POWER in Fine "Government Exhibit at Exposition. ry. 'jtr' 1 Vi 1. riofttlur Dock. 2. Battiwhlp In Dock. 3. Tj-pc-a of T"ar Vessels. 4. Hodera "aval Goiu. alongside of the naw Kearsarse to em- phasize the change and progress In TO: past 40 years. la naval architecture in tho The ttvo half- models of the old line-o- f- V .battle ships. Ohio and Washington, on the wall, show by comparison the progress of. the century. Another exhibit that has been at- tracting a great deal of attention is the Franklin life buoy, designed by a retired naval officer. It is the most effective life buoy e;er made, and a man overboard with one of these pro- tectors has a reasonable chance of res- cue., even if he Is left behind by his ship. The buoy Is annular in shape and the air chamber is made of sheet copper, divided into four water-tig- ht com- partments, in order to minimize the possibility of damage through punc- turing any portion of the chamber, and contatns 4310 cubic Inches of air space. support one man easily in a - JET' It will iiit? sitting position, and will- - sustain the weight of three men in the water when assisteJ by their own efforts. It is fitted with life chain and han- dles, and 'aa.3 automatic lighting and position torches for night signals. Two "3 metal bands, 1 by of an inch, are attached to opposite parts of the air chamber, at the outer ends of which are fitted the arrangements for carry- ing tho lighted torch when let go at. -

Does Uncle Sam Want You?

VOLUME NINE NUMBER 2 Battling for the Bill of Rights by Cheryl Baisden In 1789, when President George Washington ordered a signed copy of the proposed Bill of Rights delivered to each of the original 13 states, he probably had no idea how much trouble one of those copies would cause more than 200 years later. Today, North Carolina’s copy of the document, which contains the 12 WINTER2005 amendments that were originally proposed to the U.S. Constitution, is at the center of a $15 million lawsuit. The lawsuit involves ownership All-Volunteer Army or Military Draft: rights and the document’s mysterious journey from the North Carolina Capitol into the DoesDoes UncleUncle SamSam WantWant You?You? hands of two Connecticut men who bought it from two women by Phyllis Raybin Emert time, women between the ages of 18 and 26 to enter for $200,000. military or civilian service for two years, is still pending Businessman Robert Matthews Thousands of U.S. soldiers are stationed right now in the Senate. and antiques dealer Wayne Pratt in Korea, Afghanistan, the Balkans, Okinawa, and other bought the document in 2000 spots around the world. With our military presence in History of the draft The Civil War was the first American war where and later offered to sell it for $5 these areas and the war in Iraq, some military experts million to an FBI agent pretending claim the U.S. is spreading its forces too thin and more soldiers were drafted. This practice was also called conscription. During the Civil War, the South drafted to be a buyer for a museum.