The Case of Lexington's Town Branch Commons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAIN MAP HORSE INDUSTRY + URBAN DEVELOPMENT Aboutlexington LANDMARKS

MAIN MAP HORSE INDUSTRY + URBAN DEVELOPMENT ABOUTlexington LANDMARKS THE KENTUCKY HORSE PARK The Kentucky Horse Park is a 1,200 acre State Park and working horse farm that has been active since the 18th century. The park features approximately 50 breeds of horse and is the home to 2003 Derby Winner Funny Cide. The Park features tours, presentations, The International Museum of the Horse and the American Saddle Horse Museum as well as hosting a multitude of prestigious equine events. In the fall of 2010, the Kentucky Horse Park hosted the Alltech FEI World Equestrian Games, the first time the event has ever been held outside of Europe attracting and attendeance of over 500,000 people. The Park is also the location of the National Horse Center. that houses several equine management asso- ciations and breed organizations, The United States Equestrian Federation, The Kentucky Thoroughbred Association, The Pyramid Society, the American Hackney Horse Society, the American Hanoverian Soci- ety, U.S. Pony Clubs, Inc., among others. http://www.kyhorsepark.com/ image source: http://www.kyforward.com/tag/kentucky-horse-farms-white-fences/ MARY TODD LINCOLN’S HOME Located on Main Street in downtown Lexington, the Mary Todd Lincoln House was the family home of the future wife of Abraham Lincoln. Originally built as an inn, the property became the home of politician and businessman, Robert S. Todd in 1832. His daughter, Mary Todd, resided here until she moved to Spring- field, Illinois in 1839 to live with her elder sister. It was there that she met and married Abraham Lincoln, whom she brought to visit this home in the fall of 1847. -

Along I-64 Drive, There's a Blue and Red Buzz

Time: 03-26-2012 22:20 User: rtaylor2 PubDate: 03-27-2012 Zone: KY Edition: 1 Page Name: C6 Color: CyanMagentaYellowBlack C6 | TUESDAY,MARCH 27, 2012 | THE COURIER-JOURNAL SPORTS | courier-journal.com/sports KY NCAA MEN’S TOURNAMENT Along I-64 drive,there’sablue and redbuzz SOMEWHERE IN KENTUCKY Mike Street. that all fall into it.” way mark between the two New Year’sEve, all rolled into — OK, the dateline can’tbefound Lopresti “Youshould »10:30 a.m., Frankfort: schools, but the only signs of life one,” Mickey says. on MapQuest. But Monday was see the bank,’’she Driving into the state capital, I at this DMZ are two truck stops. As Ileave, they’re arguing the day to hit the Final Four answers. dial up the governor’soffice to »12:15 p.m. Shelbyville: with customer Keith Owens over Trail; Interstate 64, starting with United Bank is see if he might comment. “You “Fifteen miles up the road, which coach has more baggage, the University of Kentucky and the old train de- want to talk to the most conflict- you’re on the blue side,’’Tommy and Iwonder if maybe there ending with the University of pot, and there ed man in America?’’awoman Hayes explains at the Main should be no sharp objects Louisville. might be green in asks over the phone. Street Barber Shop. “Fifteen around. But how would they cut It was like driving 70-odd the cash drawers Gov.Steve Beshear is in a miles the other way,you’re on anybody’shair? miles from Lee’scamp to but blue on the budget meeting, but he has is- the red side. -

Distillery District Lexington, Ky

MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY 10 ACRES – DISTILLERY DISTRICT LEXINGTON, KY February 2019 GREYSTONE REAL ESTATE ADVISORS JEFF STIDHAM Where People Matter [email protected] 859.221.1771 PROPOSED APARTMENTS APPROX. 250 UNITS “For Illustrative Purposes Only” MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY IN THE DISTILLERY DISTRICT OF LEXINGTON, KY PROPOSED SELF-STORAGE MIXED-USE COMPONENT OFFICE | RETAIL | SELF-STORAGE “For Illustrative Purposes Only” MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY IN THE DISTILLERY DISTRICT OF LEXINGTON, KY GREYSTONE REAL ESTATE ADVISORS DISTILLERY DISTRICT MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT Lexington, KY OPPORTUNITY LEXINGTON CONVENTION CENTER CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT TOWN BRANCH PARK DISTILLERYDISTILLERY COORDINATED PUBLIC SPACE DISTRICTDISTRICT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT TOWN BRANCH TRAIL RUPP ARENA KRIKORIAN PREMIERE MANCHESTER THEATRE & BOWLING DEVELOPMENT 34 TOWNHOMES - UNDER CONSTRUCTION SUBJECT SITE 524/525 ANGLIANA STUDENT HOUSING THE LEX STUDENT HOUSING 3 MILE AERIAL SNAPSHOT RED MILE THOROUGHBRED HORSE UNIVERSITY OF RACING KENTUCKY 1.5 MILES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A Mixed-Use Development Opportunity on Approx. 10 Acres Located In Lexington, Kentucky’s Historic Distillery District. The Proposed Mixed-Use Development Will Contain A 250 Unit (Approx.) Apartment Community With Surface Parking, As Well As An Office And Retail Component. The Site Is Also Home To The Historical William McConnell House, One Of Lexington’s Most Important And Oldest Buildings. It Was Home To William McConnell, Who Was One Of Lexington’s Original Founders. This -

2018-2019 KENTUCKY HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION SPORTS SEASON REFERENCE CALENDAR (As of 3/19/19 - Tentative and Subject to Change)

2018-2019 KENTUCKY HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION SPORTS SEASON REFERENCE CALENDAR (as of 3/19/19 - tentative and subject to change) Sport First First Max # of District Regional Dates State Championship State Championship Site Practice Contest Regular Dates Dates Date Contests Leachman/ July 15 July 27 20 n/a Sept. 24 (Girls) Oct. 1-3 (Girls) Bowling Green CC, KHSAA Golf Sept. 25 (Boys) Oct. 4-6 (Boys) Bowling Green Field Hockey July 15 Aug. 13 24 n/a Oct. 15-18 Oct. 20 (QF), Oct. 22 (SF) Christian Acad.-Lou., Oct. 24 (Finals) Louisville Volleyball July 15 Aug. 6 35 Oct. 8-13 Oct. 15-20 Oct. 26-28 Valley High School, Louisville Soccer July 15 Aug. 13 21 Oct. 8-13 Oct. 15-20 Oct. 22 (Girls Semi-State) Host Sites (Semi-State), Oct. 23 (Boys Semi-State) Various Fayette County Schools Oct. 27, 31, Nov. 3 (Girls) (QFs, SFs, F) Oct. 27, Nov. 1, 3 (Boys) Lexington Cross Country July 15 Aug. 20 13 n/a Oct. 26-27 Nov. 3 Kentucky Horse Park, Lexington Football July 10 Aug. 17 10 Nov. 2-3 Nov. 16-17 (3rd Rd.) Nov. 30-Dec. 2 Kroger Field, Univ. of Kentucky, (helmet (Week 1) Nov. 9-10 Nov. 23-24 (4th Rd.) Lexington only) Aug. 1 (full gear) Competitive July 15 n/a n/a n/a Nov. 3 and Nov. 17 Dec. 8 Alltech Arena, Ky. Horse Park, Cheer Lexington Dance July 15 n/a n/a n/a Nov. 17-18 Dec. 15 Frederick Douglass HS, Lexington Bowling Oct. -

The Lexington Division of Fire And

Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government Request for Proposal The Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government hereby requests proposals for RFP #25-2016 Town Branch Commons Corridor Design Services to be provided in accordance with terms, conditions and specifications established herein. Sealed proposals will be received in the Division of Central Purchasing, Room 338, Government Center, 200 East Main Street, Lexington, KY, 40507, until 2:00 PM, prevailing local time, on August 5, 2016. Proposals received after the date and time set for opening proposals will not be considered for award of a contract and will be returned unopened to the Proposer. It is the sole responsibility of the Proposer to assure that his/her proposal is received by the Division of Central Purchasing before the date and time set for opening proposals. Proposals must be sealed in an envelope and the envelope prominently marked: RFP #25-2016 Town Branch Commons Corridor Design Services If mailed, the envelope must be addressed to: Todd Slatin - Purchasing Director Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government Room 338, Government Center 200 East Main Street Lexington, KY 40507 Additional copies of this Request For Proposals are available from the Division of Central Purchasing, Room 338 Government Center, 200 East Main Street, Lexington, KY 40507, (859)-258-3320, at no charge. Proposals, once submitted, may not be withdrawn for a period of sixty (60) calendar days. Page 1 of 47 The Proposer must submit one (1) master (hardcopy), (1) electronic version in PDF format on a flashdrive or CD and nine (9) duplicates (hardcopies) of their proposal for evaluation purposes. -

Members Headshots & Bios

Task Force on Neighborhoods in Transion Meet the Task Force Councilmember James Brown, 1st District – Task Force Chair James Brown is in his second term as 1st District Councilmember. A native of Lexington, KY, James is a graduate of Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. James’ previous employment include stints at Lexmark and GTE, before beginning a career in the automotive industry, working for 13 years at the Toyota Motor Manufacturing plant in Georgetown, KY. After that, James made a career change becoming a full-time real estate professional, selling both residential and commercial property for United Real Estate. James is extremely passionate about service to neighborhoods and the local school system. He has served as the President of the Radcliffe–Marlboro Neighborhood Association and helped initiate several neighborhood programs. In the past he served as the President of the 16th District PTA and chaired the Douglass Park Centennial. Currently, he serves as the Vice Chair of the Planning & Public Safety Committee and is on the city’s Affordable Housing Governing Board. Vice Mayor Steve Kay, At-Large Steve Kay is in his second term on Council and his first term as Lexington’s Vice Mayor. He chaired the Mayor’s Commission on Homelessness, whose recommendations informed the creation of the Office of Homelessness Prevention and Intervention, the complementary Office of Affordable Housing and the Affordable Housing Fund. He has served on the boards of the Lexington Transit Authority (LexTran), LFUCG Planning Commission, the Martin Luther King Neighborhood Association and Good Foods Co-op. While on Council, Steve continues his work as a partner of Roberts & Kay, a research and organization development firm Steve co-founded in 1983. -

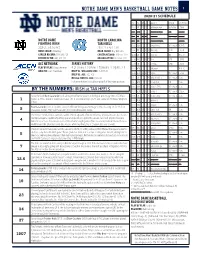

Notre Dame Men's Basketball Game Notes 1 2020-21 Schedule

NOTRE DAME MEN'S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES 1 2020-21 SCHEDULE Date Day AP C Opponent Network Time/Result 11/28 SAT 13 12 at Michigan State Big Ten Net L, 70-80 12/2 WED Western Michigan RSN canceled 12/4 FRI 13 14 Tennessee ACC Network canceled NOTRE DAME NORTH CAROLINA 12/5 SAT Purdue Fort Wayne canceled FIGHTING IRISH TAR HEELS 12/6 SUN Detroit Mercy ACC Network W, 78-70 2020-21: 3-5, 0-2 ACC 2020-21: 5-4, 0-2 ACC HEAD COACH: Mike Brey HEAD COACH: Roy Williams 12/8 TUE 22 20 & Ohio State ESPN2 L, 85-90 CAREER RECORD: 539-290 / 26 CAREER RECORD: 890-257 / 33 12/12 SAT Kentucky CBS W, 64-63 RECORD AT ND: 440-238 / 21 RECORD AT UNC: 472-156 / 18 12/16 THU 21 23 * Duke ESPN L, 65-75 ACC NETWORK SERIES HISTORY 12/19 SAT ^ vs. Purdue ESPN2 L, 78-88 PLAY BY PLAY: Doug Sherman 8-25 | Home: 3-5 | Away: 1-7 | Neutral: 4-13 | ACC: 3-8 12/23 WED Bellarmine W, 81-70 ANALYST: Cory Alexander BREY VS. WILLIAMS/UNC: 4-10/4-10 BREY VS. ACC: 102-106 12/30 WED 23 24 * Virginia ACC Network L, 57-66 ND ALL-TIME VS. ACC: 169-212 1/2 SAT * at North Carolina ACC Network 4 p.m. Full series history available on page 5 of this notes package 1/6 WED * Georgia Tech RSN 7 p.m. 1/10 SUN 24 * at Virginia Tech ACC Network 6 p.m. -

History of Kentucky Basketball Syllabus

History of Kentucky Basketball Syllabus Instructor J. Scott Course Overview Covers the history of the University of Kentucky Men’s basketball program, from its Phone inception to the modern day. This includes important coaches, players, teams and games, [Telephone] which helped to create and sustain the winning Wildcat tradition. The course will consist of in-class lectures, including by guest speakers, videos, and short Email field trips. The class will meet once a week for two hours. [Email Address] Required Text Office Location None [Building, Room] Suggested Reading Office Hours Before Big Blue, Gregory Kent Stanley [Hours, Big Blue Machine, Russell Rice Days] The Rupp Years, Tev Laudeman The Winning Tradition, Nelli & Nelli Basketball The Dream Game in Kentucky, Dave Kindred Course Materials Course materials will be provided in class, in conjunction with lectures & videos. Each student will receive a copy of the current men’s basketball UK Media Guide Resources Available online and within the UK library ! UK Archives (M.I. King Library, 2nd Floor) ! William T. Young Library ! University of Kentucky Athletics website archives: http://www.ukathletics.com/sports/m- baskbl/archive/kty-m-baskbl-archive.html ! Big Blue History Statistics website: http://www.bigbluehistory.net/bb/Statistics/statistics.html Fall Semester Page 1 Course Schedule Week Subject Homework 1 Course Structure & Requirements (15 min.) Introductory Remarks – The List (15 min.) Video: The Sixth Man (90 min.) 2 Lecture: Kentucky’s 8 National Championship Teams Take home -

Bob Watkins' Sports in Kentucky

Page 12, The Estill County Tribune, November 18, 2015 has a slightly different view. isville, the buzz is that there “Last year I saw that tent might not be enough fans at UK basketball is under grow. Commonwealth Stadium Isaac Humphries It was a huge tent. At the end Saturday to fill Rupp Arena. “The kid is really skilled. of the year, everybody was in I doubt UK fans will bail that He makes 15-footers, makes that tent. Anybody who wrote much — after all, they have free throws. Anything around about college basketball, or endured years of misery. But the goal he makes,” the UK wrote period, was trying to the loss at Vanderbilt last coach said. “When he shoots get something from this team week certainly soured the fan it, you just think it is going or staff. There were a lot of base and should have. in.” people hoping they would What would quarterback Humphries says going lose,” Pratt said. Patrick Towles say to fans? against Labissiere and Lee “I watched this team keep “We got two chances to daily have made him quickly its composure. They did not go to make the postseason. improve. get rattled. They had TV Charlotte next week and then “They are both different people go to class with them. Louisville comes to town. I players and both such good They hounded these young can tell you this every person players. It’s very good for me guys. But until the NCAA in that locker room is go- to go against them and learn Tournament, I never saw it ing to give everything they Larry Vaught how to play against that style bother them. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

E1584 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks September 5, 2001 Her ability to communicate the University’s Mr. Speaker, I ask my colleagues to join me described as one of the great radio broadcasts agenda and issues, through her remarkable in honoring the 65th Anniversary of the in the history of American horse racing. writing ability, translating complex issues to George Khoury Association of Baseball Those broadcasters who were able to un- accessible language for internal and external Leagues and to honor the many past, present, derstand and tap into the power of the human audience, helped advance many projects and and future participants in their programs. imagination are now considered the titans of initiatives. f radio’s ‘‘Golden Age’’. With the careful turn of Her advocacy of the University has resulted a phrase or the emphasis of a single word, in great gain for UMDNJ, the state of New Jer- IN MEMORY OF CAWOOD LEDFORD their listeners were as instantly transported to sey, and the health and welfare of our citi- OF HARLAN, KENTUCKY (1926–2001) another time or another place. Cawood zenry. She has played instrumental roles in Ledford, who was picked by his peers numer- the creation of the Child Health Institute of HON. HAROLD ROGERS ous times as one of the finest sports announc- New Jersey, the Cancer Institute of New Jer- OF KENTUCKY ers in the nation, was blessed with the special sey, and in working with us here in Wash- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES gift. ington to secure critical funding for AIDS/HIV, Wednesday, September 5, 2001 Those of us who vividly remember his work minority health education, environmental will have one special memory. -

Of Your Community

CELEBRATING THE ENERGY OF YOUR COMMUNITY The Voice of the Wildcats FLIP THE SWITCH for electric reliability BLUEGRASS MUSIC HALL OF FAME & MUSEUM OPENS AWARD WINNERS Beautify the Bluegrass OCTOBER 2018 • KENTUCKYLIVING.COM Dancingfrequently KENTUCKY COUNCIL www.artscouncil.ky.gov 201810 KY Arts Council.indd 1 9/6/18 11:50 AM OCTOBER 2018 VOL 72 • NO 10 2018 ENERGY ISSUE Dancingfrequently 16 30 The Voice of the Wildcats DEPARTMENTS KENTUCKY CULTURE 4 KENTUCKYLIVING.COM 38 WORTH THE TRIP COVER STORY Tom Leach may have predicted his 16 Bluegrass revival own future, but hard work and preparation played a bigger 6 YOUR COOPERATIVE COMMUNITY 43 UNIQUELY KENTUCKY role in his success. Make our communities shine Fine funeral boxes 7 COMMONWEALTHS 44 EVENTS A bench for David, pumpkins Fleming County Court Days, Beautifying Kentucky for everyone, the complex life Carter Caves Haunted Trail, a 24 Our state is more beautiful because of 23 teams of Irvin S. Cobb and more barn affair in Campbellsville, Taste of Monroe and more that put time and effort into their communities.Kentucky ON THE GRID Living and Gov. Matt Bevin’s office are recognizing the top 46 SMART HEALTH 10 FUTURE OF All about Alzheimer’s projects and cooperative participants. ELECTRICITY 47 GARDEN GURU Sun-Light Solar powers up Healthy houseplants 12 CO-OPS CARE 48 CHEF’S CHOICE The Flip of a Switch Giving back—hook, line and High-tech chocolate pie 30 Every day your lights come on, your cellphone sinker 49 GREAT OUTDOORS charges and your air (or heat) has the power to run— 13 GADGETS & GIZMOS Standing on the edge of beauty reliable electricity doesn’t “just happen.” Learn about the Pet project 50 KENTUCKY planning and precautions behind the scenes. -

BARCLAY EAST APARTMENTS LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 521 E Main St

BARCLAY EAST APARTMENTS LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 521 E Main St. Lexington, KY 40508 CONFIDENTIAL OFFERING MEMORANDUM 2 BUILDINGS | 30-UNIT CONFIDENTIALITY & DISCLAMER The information contained in the following Marketing Brochure is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from Marcus & Millichap and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Marcus & Millichap. This Marketing Brochure has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Marcus & Millichap has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB's or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant's plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. The information contained in this Marketing Brochure has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, Marcus & Millichap has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has Marcus & Millichap conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided.