Advocacy Toolkit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House Committee on Insurance Minutes of Meeting 2016 Regular

House Committee on Insurance Minutes of Meeting 2016 Regular Session May 10, 2016 I. CALL TO ORDER Representative Kirk Talbot, chairman of the House Committee on Insurance, called the meeting to order at 9:07 a.m. in Room 3, in the state capitol in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The secretary called the roll. II. ROLL CALL MEMBERS PRESENT: Representative Kirk Talbot, chairman Representative Mark Abraham Representative John F. "Andy" Anders Representative Chad Brown Representative Paula P. Davis Representative Cedric B. Glover Representative Mike Huval Representative Vincent J. Pierre Representative Alan Seabaugh Representative Major Thibaut, vice chairman MEMBERS ABSENT: Representative Robby Carter Representative Gregory Cromer Representative Paul Hollis Representative Jerome Richard STAFF MEMBERS PRESENT: David Marcase, attorney Theresa H. Ray, legislative analyst Christie L. Russell, secretary ADDITIONAL ATTENDEES PRESENT: Beverly Hurst, sergeant at arms Hunter Sikaffy, clerk Page 1 Insurance May 10, 2016 III. DISCUSSION OF LEGISLATION House Bill No. 854 by Representative Huval Representative Huval presented House Bill No. 854, which provides relative to types of motor vehicles that are required to be covered by an automobile liability policy pursuant to the Compulsory Motor Vehicle Liability Security Law. Witness cards submitted by individuals who did not speak are as follows: 1 for information only. Witness cards are included in the committee records. Representative Thibaut offered amendments in the form of a substitute bill to House Bill No. 854 Representative Thibaut offered a motion to adopt the substitute bill. Without objection, the motion passed by a vote of 9 yeas and 0 nays. Representatives Abraham, Anders, Chad Brown, Davis, Glover, Huval, Pierre, Seabaugh, and Thibaut voted yea. -

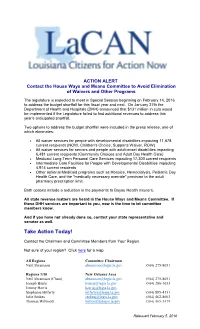

ACTION ALERT Contact the House Ways and Means Committee to Avoid Elimination of Waivers and Other Programs

ACTION ALERT Contact the House Ways and Means Committee to Avoid Elimination of Waivers and Other Programs The legislature is expected to meet in Special Session beginning on February 14, 2016 to address the budget shortfall for this fiscal year and next. On January 27th the Department of Health and Hospitals (DHH) announced that $131 million in cuts would be implemented if the Legislature failed to find additional revenues to address this year's anticipated shortfall. Two options to address the budget shortfall were included in the press release, one of which eliminates: All waiver services for people with developmental disabilities impacting 11,678 current recipients (NOW, Children's Choice, Supports Waiver, ROW) All waiver services for seniors and people with adult-onset disabilities impacting 6,481 current recipients (Community Choices and Adult Day Health Care) Medicaid Long Term Personal Care Services impacting 17,300 current recipients Intermediate Care Facilities for People with Developmental Disabilities impacting 4,914 current residents Other optional Medicaid programs such as Hospice, Hemodialysis, Pediatric Day Health Care, and the "medically necessary override" provision to the adult pharmacy prescription limit. Both options include a reduction in the payments to Bayou Health insurers. All state revenue matters are heard in the House Ways and Means Committee. If these DHH services are important to you, now is the time to let committee members know. And if you have not already done so, contact your state representative and senator as well. Take Action Today! Contact the Chairmen and Committee Members from Your Region. Not sure of your region? Click here for a map. -

C:\TEMP\Copy of 13RS

OFFICIAL JOURNAL SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 127— BY SENATOR LONG OF THE A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION To commend Colonel Mike Edmonson, Superintendent of State SENATE Police, on receiving the 2013 Buford Pusser National Law OF THE Enforcement Award. STATE OF LOUISIANA _______ Reported without amendments. THIRTY-THIRD DAY'S PROCEEDINGS SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 128— _______ BY SENATORS GALLOT, KOSTELKA, LONG, RISER AND THOMPSON AND REPRESENTATIVES SHADOIN AND JEFFERSON Thirty-Ninth Regular Session of the Legislature A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Under the Adoption of the To commend and congratulate Terry and Rosy Bromell on their Constitution of 1974 fiftieth wedding anniversary. _______ Senate Chamber Reported without amendments. State Capitol Baton Rouge, Louisiana SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 25— BY SENATOR GALLOT Tuesday, June 4, 2013 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION To urge and request the Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State The Senate was called to order at 10:20 o'clock A.M. by Hon. University and Agricultural and Mechanical College and the John A. Alario Jr., President of the Senate. governor to keep the Huey P. Long Medical Center open and viable. Morning Hour Reported without amendments. CONVENING ROLL CALL SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 57— BY SENATORS MARTINY, APPEL, CORTEZ, CROWE, GUILLORY, The roll being called, the following members answered to their JOHNS, LONG, MILLS, NEVERS, PEACOCK, PERRY, THOMPSON, names: WALSWORTH, WARD AND WHITE AND REPRESENTATIVES STUART BISHOP, BURFORD, HENRY BURNS, CARMODY, CHANEY, CONNICK, FANNIN, GUINN, HARRIS, HENRY, HILL, HODGES, HOFFMANN, PRESENT HOWARD, IVEY, LOPINTO, MACK, ORTEGO, PEARSON, POPE, PUGH, RICHARD, SCHRODER, SIMON, STOKES AND TALBOT Mr. President Erdey Peacock A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Allain Gallot Riser To urge and request the various departments to take certain actions Amedee Johns Smith, G. -

Louisiana Legislative Women's Caucus Foundation

Louisiana Legislative Women’s Caucus 2016 Election of Officers January 12, 2016 CHAIR VACANT During this past legislative session, the Women's Caucus voted to postpone SENATE VICE CHAIR their elections until after the 2016 Organizational Legislative Session. All Sen. Yvonne Dorsey-Colomb seats are open for nominations. Baton Rouge, District 14 HOUSE VICE CHAIR VACANT This will be a shortened term of office, which will last from February 8, 2016 to June 30, 2016, unless the membership votes to extend the term to June 30, IMMEDIATE PAST CHAIR Sen. Karen Carter Peterson 2017. (Note: As required under Article 14, Section 1 of the Women’s New Orleans, District 5 Caucus’ Bylaws, elections shall be held at a general membership meeting SECRETARY within the last month of the regular legislative session. After this election, the Rep. Katrina Jackson Monroe, District 16 next scheduled election will be the Women's Caucus general election in the TREASURER last month of the 2016 Regular Session for the 2016-2017 term, which will run VACANT from July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2017. PARLIAMENTARIAN Rep. Nancy Landry Lafayette, District 31 The interim chair until elections are held on February 5, 2016 is the Senate Vice-Chair of the Women's Caucus, Sen. Yvonne Dorsey-Colomb. According MEMBER AT LARGE Rep. Barbara Norton to the bylaws Article 5, Section 1, “In the absence of the Chairperson who is a Shreveport, District 3 member of the House, the Senate Vice-Chairperson, shall exercise the power SENATORS and carry out the responsibilities of the chairperson.” Regina Ashford Barrow Baton Rouge, District 15 Sharon Hewitt Nominations for the Women’s Caucus’ election of officers are to be received Slidell, District 1 no later than Wednesday, January 20, 2016 by 12:00 p.m. -

Legislative Recipients

Tulane University Legislative Scholarship Recipients 2017‐2018 Name City District Nominating Legislator Hannah Adams Franklinton Senate District 12 Beth Mizell Zachary Aucoin Morgan City Senate District 21 R.L. Allain Alanna Austin Gretna Representative District 87 Rodney Lyons Grace Authement Baton Rouge Representative District 66 Rick Edmonds Ayanna Baker Alexandria Senate District 29 Jay Luneau Gabrielle Ball Metairie Representative District 89 Reid Falconer Alexis Bell‐Pierce Saint Francisville Representative District 62 Kenny Harvard Kristin Bembenick Delhi Senate District 34 Francis Thompson Jared Bertrand Covington Representative District 74 Scott Simon Christopher Bolton Baton Rouge Representative District 6 Thomas Carmody Nicholas Bonin New Iberia Representative District 48 Taylor Barras Maarten Bravo Lafayette Representative District 31 Nancy Landry Catherine Broussard Saint Gabriel Representative District 60 Chad Brown Danielle Broussard New Iberia Representative District 96 Terry Landry Juanae Brown Baton Rouge Senate District 15 Regina Barrow Mackenzie Brown Shreveport Representative District 5 Alan Seabaugh Meghan Bush Sunset Senate District 26 Jonathan Perry Anne Caffery New Iberia Senate District 22 Fred Mills Joanna Calhoun West Monroe Representative District 15 Frank Hoffmann Caroline Campbell Baton Rouge Representative District 69 Paula Davis Christopher Carter Geismar Representative District 59 Tony Bacala Shelby Chandler Ponchatoula Repsentative District 81 Clay Schexnayder Jordan Charpentier Monterey Senate District -

Weekly Legislative Digest

Louisiana Federation of Teachers Weekly Legislative Digest May 1, 2015 Steve Monaghan, President * Les Landon, Editor 2015 Regular Legislative Session Now available on the Web at http://la.aft.org Panel votes to silence public employees Despite the best arguments of teachers, firefighters, police officers and other public servants, the House Labor and Industrial Relations Committee approved a bill that will make it inconvenient for employees to join and maintain membership in the union or association of their choice. The purpose of HB 418 by Rep. Stuart Bishop (R-Lafayette) is to weaken unions like the Louisiana Federation of Teachers and Louisiana Association of Educators. These are the groups that have raised questions about, and led the opposition to, so-called “reforms” backed by big business that all too often result in the privatization of education and diminution of the teaching profession. HB 418 would revoke the right of public employees to pay their union or association dues through payroll deduction. Since local governments currently have the authority to grant payroll deduction, the bill is seen by school boards and others as legislative meddling in their prerogatives. The bill is the brainchild of the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry, which has been twisting the arms of lawmakers to force its passage. The big business lobby recruited the Koch brothers backed Americans for Prosperity to publicly promote the bill. It is an example of what columnist Stephanie Grace, in another context, called “an ugly yet ascendant strain in American politics, a willingness to use any means necessary, no matter what chaos ensues or who gets hurt.” The vitriol motivating the bill’s supporters was on full display when an amendment was proposed to exempt the teacher unions from its prohibitions. -

The 2016 Legislature: Boomsday

Volume 42, Number 8 04/08/16 THE MISSION THE CORE VALUES of the LDAA is as follows: of LDAA members include: We believe that the Louisiana Constitution To improve Louisiana's justice system and the requires, and Louisiana citizens favor, locally- office of District Attorney by enhancing the elected, independent prosecutors. we believe that effectiveness and professionalism of Louisiana's prosecutor discretion must be protected from district attorneys and their staffs through interference through manipulative funding or education, legislative involvement, liaison and legislative restrictions. Finally, we believe that information sharing. prosecutors are the best and most trustworthy resource for legislative improvements to the criminal justice system. THE 2016 LEGISLATURE: BOOMSDAY The Governor's FY 16-17 budget is due to be released next Tuesday, April 12. When the numbers are available, we will know how the boom will be lowered concerning the DA line- item. Remember, this budget will be a worst-case scenario and will assume no additional revenues prior to July 1. The Louisiana Indigent Defender Board would be reorganized under a compromise version of HB 818. The Criminal Justice Committee approved a substitute bill, which will get a new number on the House floor. It reduces the number of Board members from 15 to 11; removes the four law professors; gives local PDs more input; and mandates that 65% of the appropriated funds be spent on local PDs. Look for LACDL and the boutique law firm, anti- death penalty gang to try to kill this in the Senate. Changing the Age of Juvenile Jurisdiction to include 17-year-olds is a major piece in the Governor's legislative agenda. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93493316048040 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code ( except black lung 2009 benefit trust or private foundation) Department of the Treasury • . Internal Revenue Service 0- The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements A For the 2009 calendar year, or tax year beginning 01 -01-2009 and ending 12 -31-2009 C Name of organization D Employer identification number B Check if applicable Please Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of fl Address change use IRS of America 53-0241211 label or Doing Business As E Telephone number F Name change print or PHRMA type . See (202) 835-3400 F Initial return Specific N um b er and st reet (or P 0 box if mai l is not d e l ivered to st ree t a dd ress) R oom/suite Instruc - 950 F Street NW G Gross receipts $ 366,684,746 F_ Terminated tions . F-Amended return City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 Washington, DC 20004 1Application pending F Name and address of principal officer H(a) Is this a group return for Billy Tauzin affiliates? fl Yes F No 950 F Street NW Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 H(b) Are all affiliates included ? fl Yes F_ No If "No," attach a list (see instructions) I Tax - exempt status F 501( c) ( 6 I (insert no ) 1 4947(a)(1) or F_ 527 H(c) Group exemption number 0- 3 Website : 1- www phrma org K Form of organization F Corporation 1 Trust F_ Association 1 Other 1- L Year of formation 1958 M State of legal domicile DE urnmar y 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities PhRMA's mission is winning advocacy for public policies that encourage the discovery of life-saving and life-enhancing new a, medicines for patients by pharmaceutical/biotechnology research companies 2 Check this box if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets 3 Number of voting members of the governing body (Part VI, line 1a) . -

Joint Meeting of the House Committee on Appropriations and the Senate Committee on Finance

Joint Meeting of the House Committee on Appropriations and the Senate Committee on Finance Minutes of Meeting 2016-2017 Interim November 18, 2016 I. CALL TO ORDER Representative Cameron Henry, Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, called the meeting to order at 12:57 p.m. in Room 5, in the state capitol in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The secretary called the roll. II. ROLL CALL MEMBERS PRESENT: Representative Cameron Henry, Chairman Representative Mark Abraham Representative Beryl A. Amedée Representative Tony Bacala Representative Lawrence A. "Larry" Bagley Representative John A. Berthelot Representative Robert E. Billiot Representative Gary M. Carter, Jr. Representative Charles R. Chaney Representative Rick Edmonds Representative Franklin J. Foil Representative Lance Harris Representative Bob Hensgens Representative Katrina R. Jackson Representative Jack G. McFarland Representative Blake Miguez Representative Dustin Miller Representative John M. Schroder, Sr. Representative Patricia Haynes Smith Representative Jerome "Zee" Zeringue MEMBERS ABSENT: Representative James K. Armes, III Representative Valarie Hodges Representative Walt Leger, III Page 1 Jt. Appropriations and Finance November 20, 2015 Representative Steve E. Pylant Representative Jerome Richard Representative Scott M. Simon Representative Julie Stokes SENATE MEMBERS PRESENT: Senator Eric LaFleur, Co-Chairman Senator R.L. Bret Allain, III Senator Conrad Appel Senator Regina Ashford Barrow Senator Norbert N. "Norby" Chabert Senator Jack Donahue Senator James R. "Jim" Fannin Senator Sharon Hewitt SENATE MEMBERS ABSENT: Senator Wesley T. Bishop Senator Ronnie Johns Senator Dan W. "Blade" Morrish Senator Gregory W. Tarver, Sr. Senator Francis C. Thompson Senator Michael A. Walsworth Senator Mack A. "Bodi" White, Jr. STAFF MEMBERS PRESENT: Ms. Katie Andress, House Committee Secretary Ms. -

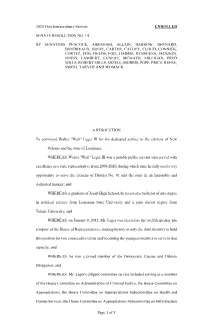

2020 First Extraordinary Session ENROLLED SENATE

2020 First Extraordinary Session ENROLLED SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 14 BY SENATORS PEACOCK, ABRAHAM, ALLAIN, BARROW, BERNARD, BOUDREAUX, BOUIE, CARTER, CATHEY, CLOUD, CONNICK, CORTEZ, FESI, FIELDS, FOIL, HARRIS, HENSGENS, JACKSON, JOHNS, LAMBERT, LUNEAU, MCMATH, MILLIGAN, FRED MILLS, ROBERT MILLS, MIZELL, MORRIS, POPE, PRICE, REESE, SMITH, TARVER AND WOMACK A RESOLUTION To commend Walter "Walt" Leger III for his dedicated service to the citizens of New Orleans and the state of Louisiana. WHEREAS, Walter "Walt" Leger III was a notable public servant who served with excellence as a state representative from 2008-2020, during which time he fully used every opportunity to serve the citizens of District No. 91 and the state in an honorable and dedicated manner; and WHEREAS, a graduate of Jesuit High School, he received a bachelor of arts degree in political science from Louisiana State University and a juris doctor degree from Tulane University; and WHEREAS, on January 9, 2012, Mr. Leger was elected as the twelfth speaker pro tempore of the House of Representatives, making history as only the third member to hold this position for two consecutive terms and becoming the youngest member to serve in that capacity; and WHEREAS, he was a proud member of the Democratic Caucus and Orleans Delegation; and WHEREAS, Mr. Leger's diligent committee service included serving as a member of the House Committee on Administration of Criminal Justice, the House Committee on Appropriations, the House Committee on Appropriations Subcommittee on Health and Human Services, -

2010 Elected Officials Guide

2011 ELECTED OFFICIALS GUIDE Beauregard Parish Louisiana Federal Officials United States President http://www.whitehouse.gov/ Barack H. Obama http://www.barackobama.com/ The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20500 202/456-1111 United States Senate United States House of Representatives 4th Congressional District Mary Landrieu http://landrieu.senate.gov/ John Fleming http://fleming.house.gov/ 724 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 1023 Longworth House Office Building 202/224-5824 Washington, DC 20515 Lake Charles Office: 202/225-2777 One Lakeshore Drive, Suite 1260 Leesville Office: Lake Charles, LA 70629 Southgate Plaza Shopping Center 337/436-6650 1606 South Fifth Street Leesville, LA 71446 David Vitter 337/238-0778 http://vitter.senate.gov/public/ 503 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 202/224-4623 Lake Charles Office: 3321 Ryan Street, Suite E Lake Charles, LA 70601 337/436-0453 State Officials Louisiana Governor http://www.gov.state.la.us/ Bobby Jindal www.bobbyjindal.com/ P.O. Box 94004 Baton Rouge, LA 70804 225/342-7015 Louisiana Lieutenant Governor Louisiana Attorney General http://www.crt.state.la.us/ltgovernor/ http://www.ag.state.la.us/ Jay Dardenne Visit this address for more details on how to contact the Capitol Annex Building Attorney General’s office. 1051 North Third Street http://www.ag.state.la.us/Article.aspx?articleID=28&catID=0 Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70802 PO Box 44243 Baton Rouge, LA 70804-4243 James D. “Buddy” Caldwell [email protected] P.O. Box 94005 Phone: (225) 342-7009 Baton Rouge, LA 70804 Fax: (225) 342-1949 225/326-6000 Louisiana Treasurer Louisiana Secretary of State http://www.treasury.state.la.us/ www.sos.louisiana.gov/ John Neely Kennedy Jay Dardenne P.O. -

74 Senate Concurrent Resolution No

OFFICIAL JOURNAL SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 123— BY SENATORS PEACOCK, ALARIO, ALLAIN, APPEL, BARROW, OF THE BISHOP, BOUDREAUX, CARTER, CHABERT, CLAITOR, COLOMB, CORTEZ, DONAHUE, ERDEY, FANNIN, GATTI, HEWITT, JOHNS, LAFLEUR, LAMBERT, LONG, LUNEAU, MARTINY, MILKOVICH, SENATE MILLS, MIZELL, MORRELL, MORRISH, PERRY, PETERSON, RISER, GARY SMITH, JOHN SMITH, TARVER, THOMPSON, WALSWORTH, OF THE WARD AND WHITE AND REPRESENTATIVES STEVE CARTER, FOIL, STATE OF LOUISIANA JAMES, EDMONDS, DAVIS AND HOFFMANN _______ A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION To commemorate the lifetime achievements of publisher and entrepreneur, Robert G. "Bob" Claitor Sr. THIRTY-FIFTH D__A__Y__'S_ PROCEEDINGS Forty-Third Regular Session of the Legislature Reported without amendments. Under the Adoption of the Constitution of 1974 SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 124— _______ BY SENATOR PEACOCK AND REPRESENTATIVES CARMODY, CREWS AND HORTON Senate Chamber A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION State Capitol To express the sincere condolences of the Legislature of Louisiana Baton Rouge, Louisiana upon the passing of Coach John Thompson, renowned football Wednesday, June 7, 2017 coach, teacher, and mentor and to celebrate his sports legacy that has spanned the greater portion of five decades. The Senate was called to order at 10:40 o'clock A.M. by Hon. John A. Alario Jr., President of the Senate. Reported without amendments. Respectfully submitted, Morning Hour ALFRED W. SPEER Clerk of the House of Representatives CONVENING ROLL CALL Message from the House The roll being called, the following members answered to their names: DISAGREEMENT TO HOUSE BILL PRESENT June 7, 2017 Mr. President Erdey Morrell To the Honorable President and Members of the Senate: Allain Fannin Morrish Appel Gatti Peacock I am directed to inform your honorable body that the House of Barrow Hewitt Perry Representatives has reconsidered to concur in the proposed Senate Bishop Johns Peterson Amendment(s) to House Bill No.