Being Metric-Wise: Heterogeneity in Bibliometric Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unnormalized and Normalized Forms of Gefura Measures in Directed and Undirected Networks*

Guns et al. / Front Inform Technol Electron Eng 2015 16(4):311-320 311 Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering www.zju.edu.cn/jzus; engineering.cae.cn; www.springerlink.com ISSN 2095-9184 (print); ISSN 2095-9230 (online) E-mail: [email protected] Unnormalized and normalized forms of gefura measures in * directed and undirected networks Raf GUNS1, Ronald ROUSSEAU‡1,2 (1Institute for Education and Information Sciences, University of Antwerp, Venusstraat 35, Antwerp B-2000, Belgium) (2Department of Mathematics, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200B, Leuven B-3001, Belgium) E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Received Dec. 9, 2014; Revision accepted Mar. 12, 2015; Crosschecked Mar. 13, 2015 Abstract: In some networks nodes belong to predefined groups (e.g., authors belong to institutions). Common network cen- trality measures do not take this structure into account. Gefura measures are designed as indicators of a node’s brokerage role between such groups. They are defined as variants of betweenness centrality and consider to what extent a node belongs to shortest paths between nodes from different groups. In this article we make the following new contributions to their study: (1) We systematically study unnormalized gefura measures and show that, next to the ‘structural’ normalization that has hitherto been applied, a ‘basic’ normalization procedure is possible. While the former normalizes at the level of groups, the latter normal- izes at the level of nodes. (2) Treating undirected networks as equivalent to symmetric directed networks, we expand the defini- tion of gefura measures to the directed case. -

The Overseas Chinese Phenomenon1

Published in: Proceedings of the ISSI 2007, D.Torres-Salinas & H.F. Moed (eds.) CSIC, Madrid, pp. 427-436 The role of ethnic ties in international collaboration: 1 the Overseas Chinese Phenomenon Bihui Jin [1] Ronald Rousseau[2] Richard P. Suttmeier[3] Cong Cao[4] [1][email protected] National Science Library of the Chinese Academy of Sciences 33 Beisihuan Xilu, Zhongguancun, Beijing, 100080 (P.R. China) [2] [email protected] KHBO, Industrial Sciences & Technology, Zeedijk 101, B-8400 Oostende (Belgium) & University of Antwerp, IBW, Universiteitsplein 1, B-2610 Wilrijk (Belgium) [3][email protected], [4] [email protected] University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA Abstract The term ‘Overseas Chinese Phenomenon’ is used here to refer to the fact that scientists of Chinese descent play an important role in international collaboration between mainland China and the rest of the world. In this paper, we review international collaboration between ethnic Chinese scientists in eight countries – USA, England, Germany, France, Japan, Canada, Australia, and South Korea – and colleagues in China itself. Our analysis shows that while ethnic ties play an important role as a bridge between China and the country of residence, policies of the Chinese government with respect to international collaboration and overseas Chinese reinforce the growth of ethnically based co-authorship. Keywords international S&T collaboration; overseas Chinese scholars; ethnic ties; government policy; ethnic collaboration index (ECI), knowledge transfer 1 The authors thank Zhang Wang, Zhou Qiuju, Yang Liying, Yang Liangbin and Wang Dan for collecting and counting data. Research for this article has been funded by a Major State Basic Research Special Program China under grant (No 2004CCC00400) and by the US National Science Foundation (OISE-0440422). -

A Multi-Metric Approach for Research Evaluations Ronald Rousseau 1,2,3 * and Fred Y

1 A multi-metric approach for research evaluations Ronald Rousseau 1,2,3 * and Fred Y. Ye 4 1VIVES (Association KU Leuven), Faculty of Engineering Technology, Zeedijk 101, 8400 Oostende, Belgium 2 Universiteit Antwerpen (UA), IBW, Stadscampus, Venusstraat 35, 2000 Antwerpen, Belgium 3 KU Leuven, 3000 Leuven, Belgium e-mail: [email protected] 4 School of Information Management, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Background information is provided related to the Web 2.0 related term altmetrics. This term is placed in the context of the broader field of informetrics. The term influmetrics is proposed as a better term for altmetrics. The importance of considering research products and not just scientific publications is highlighted. Issues related to peer review and making funding decisions within a multi-metric approach are discussed and brought in relation with the new metrics field. Keywords: altmetrics, influmetrics, multi-metric approach, informetrics, research evaluation Informetrics, a term first proposed by Nacke [1], was defined by Jean Tague-Sutcliffe [2] as follows: Informetrics is the study of the quantitative aspects of information in any form, not just records or bibliographies, and in any social group, not just scientists. Thus it looks at the quantitative aspects of informal or spoken communication, as well as recorded, and of information needs and uses of the disadvantaged, not just the intellectual elite. Since then this definition has been accepted and its use supported by many workers in the field, (so-called informetricians) such as Wilson [3], Ingwersen and Björneborn * Corresponding author 2 [4], Bar-Ilan [5] and Rousseau [6]. -

COLLNET 2019 Program.Pdf

The 15th International Conference on Webometrics, Informetrics, The 15th International Conference on Webometrics, Informetrics, & Scientometrics (WIS) & the 20th COLLNET Meeting & Scientometrics (WIS) & the 20th COLLNET Meeting Finally for Friday, 8 November we have scheduled three plenary talks: Welcome to COLLNET 2019 Lin Zhang (Wuhan University, China) Gender, age and broader impact • Tao Jia (Southwest University, China) Science knows no country, but citations do: the west and east of science community • Zhigang Hu (WISELab in Dalian University of Technology, China) The 15th International Conference on Webometrics, Informetrics and Scientometrics & 20th COLLNET Meeting Four pitfalls in normalizing citation indicators: An investigation of ESI’s selection of highly cited papers (COLLNET2019) will be held on 5-8 November 2019 in Dalian (China). The meeting is hosted by the WISE Lab at Dalian University of Technology (DUT). Parallel sessions of paper presentations COLLNET2019 is a major event attended by about 100 registered participants from more than ten countries and Full papers and research-in-progress papers have been assigned to the following five topics: regions all over the world. 1. Altmetrics (5 papers) The conference includes a special virtual presentation of science mapping organized in collaboration with the 2. Science of science (7 papers) “Cyberinfrastructure for Network Science Center”at Indiana University. 3. New indicators (7 papers) After two rounds of reviewing by the program committee only 45 out of the 120 previously submitted papers 4. Patent and technology innovation (10 papers) were retained as full paper for oral presentation, while authors of further 30 submissions were invited for poster 5. Country and regional studies (9 papers) presentation. -

A Comprehensive Analysis of the Journal Evaluation System in China

RESEARCH ARTICLE A comprehensive analysis of the journal evaluation system in China Ying Huang1,2 , Ruinan Li1 , Lin Zhang1,2 , and Gunnar Sivertsen3 1School of Information Management, Wuhan University, China 2Centre for R&D Monitoring (ECOOM) and Dept. MSI, KU Leuven, Belgium an open access journal 3Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education, Tøyen, Oslo, Norway Keywords: bibliometrics, journal evaluation, peer review, science journal ABSTRACT Citation: Huang, Y., Li, R., Zhang, L., & Journal evaluation systems reflect how new insights are critically reviewed and published, and Sivertsen, G. (2020). A comprehensive analysis of the journal evaluation the prestige and impact of a discipline’s journals is a key metric in many research assessment, system in China. Quantitative Science Studies, 2(1), 300–326. https://doi.org performance evaluation, and funding systems. With the expansion of China’s research and /10.1162/qss_a_00103 innovation systems and its rise as a major contributor to global innovation, journal evaluation has DOI: become an especially important issue. In this paper, we first describe the history and background https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00103 of journal evaluation in China and then systematically introduce and compare the most currently Received: 30 April 2020 influential journal lists and indexing services. These are the Chinese Science Citation Database Accepted: 18 September 2020 (CSCD), the Journal Partition Table (JPT), the AMI Comprehensive Evaluation Report (AMI), the “ ” Corresponding Author: Chinese S&T Journal Citation Report (CJCR), A Guide to the Core Journals of China (GCJC), Lin Zhang the Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI), and the World Academic Journal Clout [email protected] Index (WAJCI). -

22-Ronald Rousseau.Indd

Research Paper Equalities between h-type Indices and Definitions of Rational h-type Indicators Leo Egghe1, Yves Fassin2, Ronald Rousseau3,4† 1University of Hasselt, Belgium 2Department of Marketing, Innovation and Organisation, Faculty of Economics and Business Citation: Leo Egghe, Administration, Ghent University, Tweekerkenstraat, 2, 9000 Gent, Belgium Yves Fassin, Ronald 3 Rousseau (2019). University of Antwerp, Faculty of Social Sciences, Middelheimlaan 1, 2020, Antwerpen, Equalities between h-type Belgium indices and definitions of 4KU Leuven, Facultair Onderzoekscentrum ECOOM, Naamsestraat 61, 3000 Leuven, rational h-type indicators. Belgium Vol. 4 No. 1, 2019 pp 22–31 DOI: 10.2478/jdis-2019-0002 Abstract Received: Nov. 24, 2018 Revised: Dec. 8, 2018 Purpose: To show for which publication-citation arrays h-type indices are equal and to Accepted: Dec. 11, 2018 reconsider rational h-type indices. Results for these research questions fill some gaps in existing basic knowledge about h-type indices. Design/methodology/approach: The results and introduction of new indicators are based on well-known definitions. Findings: The research purpose has been reached: answers to the first questions are obtained and new indicators are defined. Research limitations: h-type indices do not meet the Bouyssou-Marchant independence requirement. Practical implications: On the one hand, more insight has been obtained for well-known indices such as the h- and the g-index and on the other hand, simple extensions of existing indicators have been added to the bibliometric toolbox. Relative rational h-type indices are more useful for individuals than the existing absolute ones. Originality/value: Answers to basic questions such as “when are the values of two h-type indices equal” are provided. -

Basic Independence Axioms for the Publication- Citation System

JSCIRES RESEARCH ARTICLE Basic independence axioms for the publication- citation system Ronald Rousseau a,b,c and Fred Y Ye d,e *aKHBO (Association KU Leuven), Faculty of Engineering Technology, Zeedijk 101, B-8400 Oostende, Belgium bKU Leuven, Dept. Mathematics, Celestijnenlaan 200B, B-3000 Leuven (Heverlee), Belgium cUniversiteit Antwerpen, IBW, Venusstraat 35, B-2000 Antwerpen, Belgium dDept. Information Resources Management, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027, China eSchool of Information Management, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China ABSTRACT Following the idea of the Bouyssou-Marchant independence axiom, a basic independence axiom for an indicator is introduced. It is shown that the average number of citations nor the h-index satisfy this basic axiom. Among the indicators considered here only the number of publications and the number of citations satisfy the requirements of this axiom. Weaker forms of the basic independence axiom are considered. The number of citations of the most-cited article satisfies these weaker forms. When studying the h-index the notion of an h-critical publication is introduced. Keywords: Independence; consistency; publications; citations; indicators; h-index. INTRODUCTION This independence axiom for an indicator f (any!) can be formulated as follows. Let f(S) ≤ f(T), where f(S), resp. f(T), In recent years it has come to the attention of informetri- denotes the value of the indicator f derived from sets of cians that basic indicators used for research evaluation do articles written by scientist S, resp. scientist T. If one adds not always have the properties one might expect. A well- now to both sets an article with n (a natural number) cita- known example is the discussion between ratios of averages tions, then the axiom requires that the relation f(S) ≤ f(T) and averages of ratios (or in other words, between the origi- must still hold. -

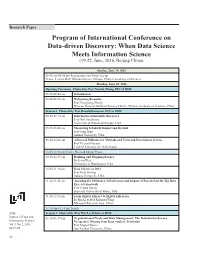

Program of International Conference on Data-Driven Discovery: When Data Science Meets Information Science (19-22, June, 2016, Beijing China)

Research Paper Program of International Conference on Data-driven Discovery: When Data Science Meets Information Science (19-22, June, 2016, Beijing China) Sunday, June 19, 2016 08:30 am-08:30 pm Registration and Poster Set-up Venue: Lecture Hall, National Science Library, Chinese Academy of Sciences Monday, June 20, 2016 Opening Ceremony Chaired by Prof Xiaolin Zhang, EIC of JDIS 08:30-08:40 am Introduction 08:40-08:50 am Welcoming Remarks Prof Xiangyang Huang Director General, National Science Library, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China Session 1 Chaired by Prof Ronald Rousseau, EIC of JDIS 08:50-09:15 am Informatics of Scientific Discovery Prof Neil Smalheiser University of Illinois at Chicago, USA 09:15-09:40 am Measuring Scholarly Impact and Beyond Prof Ying Ding Indiana University, USA 09:40-10:05 am Advanced Bibliometric Methods and Tools and Information Science Prof Everard Noyons Leiden University, the Netherlands 10:05-10:30 am Coffee Break & Group Photo 10:30-10:55 am Ranking and Mapping Science Dr Jevin West University of Washington, USA 10:55-11:20 am Data Science in 2021 Prof Kyle Stirling Indiana University, USA 11:20-11:45 am Assessing the Efficiency, Effectiveness and Impact of Research in the Big Data Era: A framework Prof Cinzia Daraio Sapienza University of Rome, Italy 11:45-12:10 am From Digital Library to Digital Librarian Dr Rui Li & Prof Kuansan Wang Microsoft Research Asia, China 12:10 am-01:10 pm Lunch JDIS Session 2 Chaired by Prof Wei Lu, Editor of JDIS Journal of Data and 01:10-01:35 pm Organizational Needs and Data Management: The Information Science Information Science Perspective Missing from Data Analytic Textbooks Vol. -

Understanding Patterns of International Scientific Collaboration Ronald Rousseau

Journal of Scientometric Res. 2021; 10(1):126-129 http://www.jscires.org Research Note Going Back in Time: Understanding Patterns of International Scientific Collaboration Ronald Rousseau University of Antwerp, Faculty of Social Sciences, B-2020 Antwerp, Belgium and KU Leuven, Facultair Onderzoekscentrum ECOOM, Naamsestraat, Leuven B - 3000, BELGIUM. Correspondence ABSTRACT Ronald Rousseau We study the interpretation of the observed/expected ratio as an indicator of international University of Antwerp, Faculty of Social scientific collaboration. This indicator cannot be considered as representing the affinity for collaboration, in the sense of ‘the more the better’, between two countries. Sciences, B-2020 Antwerp, Belgium and KU Leuven, Facultair Onderzoekscentrum Keywords: International collaboration, Observed/expected ratio, Indicators, Activity index, ECOOM, Naamsestraat 61, Axiomatic approach. Leuven B 3000, BELGIUM. Email id: [email protected] INTRODUCTION Received: 20-01-2021 Revised: 13-02-2021 Accepted: 21-02-2021 In 1992 Luukkonen, Persson and Sivertsen published a well- DOI: 10.5530/jscires.10.1.15 known article entitled “Understanding patterns of international scientific collaboration” in the journal Science, Technology, and [1] Human Values. Nowadays (January 2021) it is cited 326 times CCXY,,XY in the Web of Science (WoS). This places the article in the top CCXY OER(,) X Y == (1) position of articles published in this journal in 1992, and at the CCYX th 11 place of all articles in this journal published since 1980. TT Luukkonen .[1] noted that international scientific et al where C denotes the number of collaborations between collaboration has increased both in volume and importance, a X,Y countries X and Y (whole counting); CX the total number point that holds even more nowadays. -

Chemical Engineering Science

CHEMICAL ENGINEERING SCIENCE AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 0009-2509 DESCRIPTION . Chemical Engineering Science has an open access mirror Chemical Engineering Science: X which has the same aims and scope, editorial board and peer-review process. To submit to Chemical Engineering Science: X visit https://www.editorialmanager.com/CESX/default.aspx. Chemical Engineering Science (CES) has been publishing papers on the fundamentals of chemical engineering since 1951. CES is the platform where the most significant advances in the discipline have ever since been published. Chemical Engineering Science has accompanied and sustained chemical engineering through its development into the vibrant and broad scientific discipline it is today. We welcome manuscripts presenting cutting-edge research, of either an experimental or a theoretical nature. While centered in chemical engineering, manuscripts will often have scope that cuts across disciplines, ranges across scales, from the molecular level to the plant level, with impact not only on specific research questions but also in global issues. Critical reviews of cutting-edge developments are also considered. Papers submitted to Chemical Engineering Science are assessed by the editorial board via a thorough peer-review process only with regard to their quality and potential for fundamental and long-lasting contribution to chemical engineering. Chemical Engineering Science classifies research into the following main fields: Biochemical engineering, Materials synthesis and processing, Particle technology, Process systems engineering, Reaction engineering and catalysis, Separation processes, Thermodynamics and Soft Matter, and Transport Phenomena including Fluid Mechanics. -

AN OUTGROW INDEX Vol

Annals of Library and Information Studies ROUSSEAU & HU: AN OUTGROW INDEX Vol. 57, Sept 2010, pp. 287-290 287 An outgrow index Ronald Rousseau 1,2,3 and Xiaojun Hu4,5 1 KHBO (Association K.U.Leuven), Industrial Sciences and Technology, Zeedijk 101, B-8400 Oostende, Belgium 2University of Antwerp, IBW, Venusstraat 35, B-2000 Antwerpen, Belgium 3 K.U.Leuven, Dept. Mathematics, Celestijnenlaan 200B, B-3000 Leuven (Heverlee), Belgium, E-mail: [email protected] 4College of Public Administration, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China 5Medical Information Centre, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China, E-mail: [email protected] Proposes a relative index measuring the amount by which an article outgrows, in terms of citations, the publications on which it is based. The study involves citations collected from Web of Science during the last week of April 2010 along with the number of citations received (also in WoS) by each of the references. Introduction To do this, we stand on the shoulders of Eugene Garfield’s We define citation analysis as that subfield of life work (actually a part of, as his realizations go far informetrics where patterns and frequencies of citations, beyond the one used here), namely the Web of Science given as well as received are analyzed. Such an analysis (WoS). is performed on the level of authors, journals, scientific disciplines and any other useful unit or level. Citation Methodology analysis further studies relations between cited and citing units (documents, authors, countries etc.). From We consider articles, mainly published in journals included an application point of view citation analysis may be in the JCR subject category Medical, General & considered as a collaborative peer effort to analyze and Internal, collected the number of received citations, with promote the quality of scholarly publication and and without author self-citations (data were collected from research1,2. -

22-Ronald Rousseau.Indd

Research Paper Equalities between h-type Indices and Definitions of Rational h-type Indicators Leo Egghe1, Yves Fassin2, Ronald Rousseau3,4† 1University of Hasselt, Belgium 2Department of Marketing, Innovation and Organisation, Faculty of Economics and Business Citation: Leo Egghe, Administration, Ghent University, Tweekerkenstraat, 2, 9000 Gent, Belgium Yves Fassin, Ronald 3 Rousseau (2019). University of Antwerp, Faculty of Social Sciences, Middelheimlaan 1, 2020, Antwerpen, Equalities between h-type Belgium indices and definitions of 4KU Leuven, Facultair Onderzoekscentrum ECOOM, Naamsestraat 61, 3000 Leuven, rational h-type indicators. Belgium Vol. 4 No. 1, 2019 pp 22–31 DOI: 10.2478/jdis-2019-0002 Abstract Received: Nov. 24, 2018 Revised: Dec. 8, 2018 Purpose: To show for which publication-citation arrays h-type indices are equal and to Accepted: Dec. 11, 2018 reconsider rational h-type indices. Results for these research questions fill some gaps in existing basic knowledge about h-type indices. Design/methodology/approach: The results and introduction of new indicators are based on well-known definitions. Findings: The research purpose has been reached: answers to the first questions are obtained and new indicators are defined. Research limitations: h-type indices do not meet the Bouyssou-Marchant independence requirement. Practical implications: On the one hand, more insight has been obtained for well-known indices such as the h- and the g-index and on the other hand, simple extensions of existing indicators have been added to the bibliometric toolbox. Relative rational h-type indices are more useful for individuals than the existing absolute ones. Originality/value: Answers to basic questions such as “when are the values of two h-type indices equal” are provided.