Rescuing Childhood: Representing the Orphan Trains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kristen Connolly Helps Move 'Zoo' Far Ahead

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad We’ve got you covered! June 23 - 29, 2017 waxahachietx.com U J A M J W C Q U W E V V A H 2 x 3" ad N A B W E A U R E U N I T E D Your Key E P R I D I C Z J Z A Z X C O To Buying Z J A T V E Z K A J O D W O K W K H Z P E S I S P I J A N X and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad A C A U K U D T Y O W U P N Y W P M R L W O O R P N A K O J F O U Q J A S P J U C L U L A Co-star Kristen Connolly L B L A E D D O Z L C W P L T returns as the third L Y C K I O J A W A H T O Y I season of “Zoo” starts J A S R K T R B R T E P I Z O Thursday on CBS. O N B M I T C H P I G Y N O W A Y P W L A M J M O E S T P N H A N O Z I E A H N W L Y U J I Z U P U Y J K Z T L J A N E “Zoo” on CBS (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Jackson (Oz) (James) Wolk Hybrids Place your classified Solution on page 13 Jamie (Campbell) (Kristen) Connolly (Human) Population ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad Mitch (Morgan) (Billy) Burke Reunited Light, Midlothian1 xMirror 4" ad and Abraham (Kenyatta) (Nonso) Anozie Destruction Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Dariela (Marzan) (Alyssa) Diaz (Tipping) Point Kristen Connolly helps Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it move ‘Zoo’ far ahead 2 x 3.5" ad 2 x 4" ad 4 x 4" ad 6 x 3" ad 16 Waxahachie Daily Light Cardinals. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

Hit the Road

FINAL-1 Sat, May 25, 2019 6:09:43 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of June 2 - 8, 2019 Hit the road Ashleigh Cummings stars in “NOS4A2” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 Artist Vic McQueen (Ashleigh Cummings, “Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries”) has supernatural powers that allow her to see across space and time in “NOS4A2,” which premieres Sunday, June 2, on AMC. These powers lead her to a nefarious and immortal soul sucker named Charlie Manx (Zachary Quinto, “Hotel Artemis,” 2018), and the two square off for an epic battle between good and evil. The horror series is based on the best-selling novel by Joe Hill, son of the legendary Stephen King. WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS To advertise here GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL please call ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES (978) 946-2375 We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC INSPECTIONS CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, May 25, 2019 6:09:44 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 CHANNEL Kingston Sports Highlights Atkinson Londonderry 10:00 p.m. -

FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini

Pat McCorkle, CSA Jeffrey Dreisbach, Casting Partner Katja Zarolinski, CSA Kristen Kittel, Casting Assistant FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini. Starring: William Shatner, Christopher Lloyd, Jean Smart. THE MURPHYS (Independent Feature; Producer(s): The Murphy's LLC). Director: Kaitlan McGlaughlin. BERNARD & HUEY (In production. Independent Feature; Producer(s): Dan Mervish/Bernie Stein). Director: Dan Mervish. AFTER THE SUN FELL (Post Production. Independent feature; Producer(s): Joanna Bayless). Director: Tony Glazer. Starring: Lance Henriksen, Chasty Ballesteros, Danny Pudi. FAIR MARKET VALUE (Post Production. Feature ; Producer(s): Judy San Romain). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Jerry Adler, D.C. Anderson, Michael J. Arbouet. YEAR BY THE SEA (Festival circuit. Feature; Producer(s): Montabella Productions ). Director: Alexander Janko. Starring: Karen Allen, Yannick Bisson, Michael Cristofer. CHILD OF GRACE (Lifetime Network Feature; Producer(s): Empathy + Pictures/Sternamn Productions). Director: Ian McCrudden. Starring: Ted Lavine, Maggy Elizabeth Jones, Michael Hildreth. POLICE STATE (Independent Feature; Producer(s): Edwin Mejia\Vlad Yudin). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Sean Young, Seth Gilliam, Christina Brucato. MY MAN IS A LOSER (Lionsgate, Step One Entertainment; Producer(s): Step One of Many/Imprint). Director: Mike Young. Starring: John Stamos, Tika Sumpter, Michael Rapaport. PREMIUM RUSH (Columbia Pictures; Producer(s): Pariah). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. JUNCTION (Movie Ranch; Producer(s): Choice Films). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. GHOST TOWN* (Paramount Pictures; Producer(s): Dreamworks SKG). Director: David Koepp. Starring: Ricky Gervais, Tea Leoni, Greg Kinnear. WAR EAGLE (Empire Film; Producer(s): Downstream Productions). Director: Robert Milazzo. Starring: Brian Dennehy, Mary Kay Place, Mare Winningham. -

Original Wile~ Rein & Fielding

ORIGINAL WILE~ REIN & FIELDING 1776 K STREET, N. W. WASHINGTON, O. c. 20006R~" "',"",,-~-.~ !,~ (202) 429-7000 .. DON NA COLEMAN GREGG J L"1'1. FACSIMILE (202) 429-7260 (202) 429-7049 July 18, 1997 Mr. William F. Caton, Secretary Federal Communications Commission 1919 M Street, Northwest Washington, D. C. 20554 Re: Notification Q/Permitted Ex Parte Presentation ion in MM Docket No. 95-176 Dear Mr. Caton: Lifetime Television ("Lifetime''), by its attorneys and pursuant to Section 1.206{a){I) of the Commission's rules, hereby submits an original and one copy ofa notification ofex parte contact in MM Docket No. 95-176. Nancy R. Alpert, Senior Vice President ofBusiness and Legal Affairs and Deputy General Counsel at Lifetime, Gwynne McConkey, Vice President ofNetwork Operations at Lifetime, along with Donna C. Gregg ofWiley, Rein & Fielding, met with Anita Wallgren, Legal Advisor to Commissioner Susan Ness, and Marsha MacBride, Legal Advisor to Commissioner James Quello, to discuss issues related to the above-cited docket and summarized in the written materials attached hereto. Kindly direct any questions regarding this matter to the undersigned counseL Respectfully submitted, \A \...!/~-u:t- Donna C. Gregg Counsel for Lifetime Television Enclosures Lifetime Closed Captioning - July 18, 1997 • Since it was established in 1984, Lifetime Television has become the premier network of "television for women." Lifetime currently reaches over 68 million households (over 90% of all cable homes) and is ranked fifth among all basic cable services in -

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GEM Sun Apr 10, 2011 06:00 IT IS WRITTEN HD WS PG Touch Of Freedom: He Saved Me From The Sidelines Religious programme. 06:30 ON THE FIDDLE 1961 G On the Fiddle Two London con artists enlist in the Army, one to avoid going to jail and the other for a rest cure. Army life is a series of hilarious misadventures for them until they are posted overseas, where they become heroes. Starring: Sean Connery, Alfie Lynch, Cecil Parker, Stanley Holloway, Alan King 08:30 SEA DEVILS 1953 Repeat WS G Sea Devils Gilliatt, a fisherman-turned-smuggler on the isle of Guernsey, agrees to transport a beautiful woman to the French coast in the year 1800. Gilliatt finds himself falling in love and so feels betrayed when he later learns this woman is a countess helping Napoleon plan an invasion of England. Starring: Rock Hudson, Yvonne De Carlo, Maxwell Reed 10:30 JULES VERNE'S ROCKET TO THE MOON 1967 Repeat WS G Jules Verne's Rocket To The Moon Having narrowly escaped the clutches of an outraged army of creditors, the great showman Phineas T Barnum, with only the smallest of his assets, General Tom Thumb, arrives in England to start a new life. He soon finds something fresh to exploit in the shape of 'Bulovite', a new explosive which its ebullient German inventor, Von Bulow, claims would be powerful enough to propel a projectile to the moon. Starring: Burl Ives, Troy Donahue, Gert Frobe, Dennis Price, Lionel Jeffries 12:55 THE YELLOW ROLLS-ROYCE 1964 WS G The Yellow Rolls-Royce Three stories about the lives and loves of those who own a certain yellow Rolls-Royce. -

WAB Wisconsin Arts News

May 25, 2018 In The News | When You Go | Opportunities | Subscribe/Unsubscribe Please “like” the Arts Board on Facebook and follow us on Twitter. The Wisconsin Arts Board will be closed Monday, May 28, in observance of Memorial Day. QUOTE(S) OF THE DAY “The defining function of the artist is to cherish consciousness.” – Max Eastman “Acting is a very big part of what human beings do. A dog is always a dog, but we're always changing.” – Ian Mckellen “I'm not an optimist. I'm a realist. And my reality is that we live in a multifaceted, multicultural world. And maybe once we stop labeling ourselves, then maybe everyone else will.” – Octavia Spencer “Even if you're on the right track, you'll get run over if you just sit there.” – Will Rogers “Swimming is a confusing sport, because sometimes you do it for fun, and other times you do it to not die. And when I'm swimming, sometimes I'm not sure which one it is.” – Demetri Martin “Sing out loud in the car even, or especially, if it embarrasses your children.” – Marilyn Penland VIDEO(S) OF THE DAY The Arts Page Program #608 Theater Is for Everyone The Arts Page | Milwaukee PBS Young Conductor Keeps Oldest German Men’s Choir Singing Wisconsin Life The NSO Performs "The Armed Forces Medley" Capitol Concerts Wisconsin artists and arts organizations, do you have video that you’d like us to consider sharing as the Wisconsin Arts News Video of the Day? Send the link to [email protected]! TOP WISCONSIN NEWS FROM THE WISCONSIN ARTS BOARD Associate Academy Director/Director of Next Steps First Stage -

Movies That Will Get You in the Holiday Spirit

Act of Violence 556 Crime Drama A Adriana Trigiani’s Very Valentine crippled World War II veteran stalks a Romance A woman tries to save her contractor whose prison-camp betrayal family’s wedding shoe business that is caused a massacre. Van Heflin, Robert teetering on the brink of financial col- Alfred Molina, Jason Isaacs. (1:50) ’11 Ryan, Janet Leigh, Mary Astor. (NR, 1:22) lapse. Kelen Coleman, Jacqueline Bisset, 9 A EPIX2 381 Feb. 8 2:20p, EPIXHIT 382 ’49 TCM 132 Feb. 9 10:30a Liam McIntyre, Paolo Bernardini. (2:00) 56 ’19 LIFE 108 Feb. 14 10a Abducted Action A war hero Feb. 15 9a Action Point Comedy D.C. is the takes matters into his own hands About a Boy 555 Comedy-Drama An crackpot owner of a low-rent amusement Adventures in Love & Babysitting A park where the rides are designed with Romance-Comedy Forced to baby- when a kidnapper snatches his irresponsible playboy becomes emotion- minimum safety for maximum fun. When a sit with her college nemesis, a young young daughter during a home invasion. ally attached to a woman’s 12-year-old corporate mega-park opens nearby, D.C. woman starts to see the man in a new Scout Taylor-Compton, Daniel Joseph, son. Hugh Grant, Toni Collette, Rachel Weisz, Nicholas Hoult. (PG-13, 1:40) ’02 and his loony crew of misfits must pull light. Tammin Sursok, Travis Van Winkle, Michael Urie, Najarra Townsend. (NR, out all the stops to try and save the day. Tiffany Hines, Stephen Boss. (2:00) ’15 1:50) ’20 SHOX-E 322 Feb. -

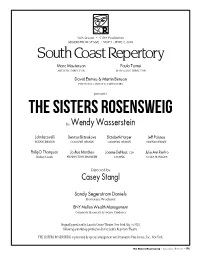

The Sisters Rosensweig Program

SC 54th Season • 519th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / MAY 5 - JUNE 2, 2018 Marc Masterson Paula Tomei ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR David Emmes & Martin Benson FOUNDING ARTISTIC DIRECTORS presents THE SISTERS ROSENSWEIG by Wendy Wasserstein John Iacovelli Denitsa Bliznakova Elizabeth Harper Jeff Polunas SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Philip D. Thompson Joshua Marchesi Joanne DeNaut, CSa Julie Ann Renfro Dialect Coach PRODUCTION MANAGER CASTING STAGE MANAGER Directed by Casey Stangl Sandy Segerstrom Daniels Honorary Producer BNY Mellon Wealth Management Corporate Honorary Associate Producer Originally produced by Lincoln Center Theater, New York City, in 1992, following a workshop production by the Seattle Repertory Theatre. THE SISTERS ROSENSWEIG is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc., New York. The Sisters Rosensweig • South CoaSt RepeRtoRy • P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Tess Goode ............................................................................................... Emily James Pfeni Rosensweig ...................................................................................... Betsy Brandt Sara Goode ............................................................................................... Amy Aquino Geoffrey Duncan .................................................................................. Bill Brochtrup Mervyn Kant .......................................................................................... Matthew Arkin Gorgeous -

Download Full

Jill Eikenberry Award-winning actress Jill Eikenberry is perhaps best known for her portrayal of Ann Kelsey on NBC's long-running hit series L.A. Law. In addition to appearing in numerous television movies and feature films, Eikenberry has earned four Emmy nominations, two Golden Globe nominations and a Golden Globe Award. Upon graduating from Barnard College in New York and Yale Drama School in Connecticut, Eikenberry embarked on an extensive theater career on and off Broadway, including roles in "Beggars Opera," "All Over Town" directed by Dustin Hoffman, Wendy Wasserstein's "Uncommon Women," in which she also appeared opposite Meryl Streep in the PBS TV version, Tennessee Williams' "The Eccentricities of a Nightingale," "Watch on the Rhine," and "Onward Victoria." For her performances in Lanford Wilson's "Lemon Sky" and in Richard Greenberg's "Life Under Water," she was recognized with Obie Awards. Eikenberry made her feature film debut in 1976 in Between the Lanes opposite John Heard and Jeff Goldblum. She then starred in Rich Kids with John Lithgow; Butch and Sundance: The Early Days, Hide in Plain Sight, with James Caan; Arthur, where she played Dudley Moore's jilted fiancée, and again opposite John Lithgow in The Manhattan Project. Having conquered theater and film, Eikenberry turned to television, starring first in ABC's Swansong, then in CBS' Orphan Train and later, to many other popular programs including Hill Street Blues. Most recently she completed an independent feature film entitled Manna from Heaven, and has guest-starred on television series' such as Strong Medicine, Judging Amy, and performed on stage in "The Vagina Monologues." After adding breast cancer survivor to her extensive resume, Eikenberry co-produced a one- hour documentary for NBC entitled Destined to Live, which focused on the emotional aspects of breast cancer, from diagnosis to recovery. -

ROYALE THEATER, 242-250 West 45Th Street, Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission December 15, 1987; Designation List 198 LP-1372 ROYALE THEATER, 242-250 West 45th Street, Manhattan. Built 1926-27; architect Herbert J. Krapp. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1016, Lot 55. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Royale Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 68). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty-two witnesses spoke or had statements read into the record in favor of designation. One witness spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indica ted that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Royale Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in 1926- 27, the Royale was among the half-dozen theaters constructed by the Chanin Organization in the mid-1920s, to the designs of Herbert J. Krapp, that typified the development of the Times Square/Broadway theater district. Founded by Irwin S. Chanin, the Chanin organization was a major cons true tion company in New York. During the 1920s, Chanin branched out into the building of theaters, and helped create much of the ambience of the heart of the theater district. -

On Film: a Social History of Women Lawyers in Popular Culture 1930-1990

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 14 Number 1 Article 3 9-1-1993 On Film: A Social History of Women Lawyers in Popular Culture 1930-1990 Ric Sheffield Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ric Sheffield, On Film: A Social History of Women Lawyers in Popular Culture 1930-1990, 14 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 73 (1993). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol14/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON FILM: A SOCIAL HISTORY OF WOMEN LAWYERS IN POPULAR CULTURE 1930 TO 1990 Ric Sheffield I. INTRODUCTION The year 1929 remains indelibly imprinted in the minds of millions of Americans as the year of the great stock market crash. To most, American society would never again be the same. 1929 was also an important year in the history of popular culture in that the Academy Awards were presented for the first time; Station WGY in Schenectady, New York, was the first to broadcast a regular television schedule; the infamous but popular Amos N' Andy radio show made its national premiere; and American cinema began production of its first portrayal of a fictional woman attorney. A crash of another sort, the introduction of the motion picture industry's first big-screen "lady lawyers," irreversibly changed the face of the lawyer-courtroom film genre.