Severe Weather

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Are We Doing with (Or To) the F-Scale?

5.6 What Are We Doing with (or to) the F-Scale? Daniel McCarthy, Joseph Schaefer and Roger Edwards NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center Norman, OK 1. Introduction Dr. T. Theodore Fujita developed the F- Scale, or Fujita Scale, in 1971 to provide a way to compare mesoscale windstorms by estimating the wind speed in hurricanes or tornadoes through an evaluation of the observed damage (Fujita 1971). Fujita grouped wind damage into six categories of increasing devastation (F0 through F5). Then for each damage class, he estimated the wind speed range capable of causing the damage. When deriving the scale, Fujita cunningly bridged the speeds between the Beaufort Scale (Huler 2005) used to estimate wind speeds through hurricane intensity and the Mach scale for near sonic speed winds. Fujita developed the following equation to estimate the wind speed associated with the damage produced by a tornado: Figure 1: Fujita's plot of how the F-Scale V = 14.1(F+2)3/2 connects with the Beaufort Scale and Mach number. From Fujita’s SMRP No. 91, 1971. where V is the speed in miles per hour, and F is the F-category of the damage. This Amazingly, the University of Oklahoma equation led to the graph devised by Fujita Doppler-On-Wheels measured up to 318 in Figure 1. mph flow some tens of meters above the ground in this tornado (Burgess et. al, 2002). Fujita and his staff used this scale to map out and analyze 148 tornadoes in the Super 2. Early Applications Tornado Outbreak of 3-4 April 1974. -

Squall Lines: Meteorology, Skywarn Spotting, & a Brief Look at the 18

Squall Lines: Meteorology, Skywarn Spotting, & A Brief Look At The 18 June 2010 Derecho Gino Izzi National Weather Service, Chicago IL Outline • Meteorology 301: Squall lines – Brief review of thunderstorm basics – Squall lines – Squall line tornadoes – Mesovorticies • Storm spotting for squall lines • Brief Case Study of 18 June 2010 Event Thunderstorm Ingredients • Moisture – Gulf of Mexico most common source locally Thunderstorm Ingredients • Lifting Mechanism(s) – Fronts – Jet Streams – “other” boundaries – topography Thunderstorm Ingredients • Instability – Measure of potential for air to accelerate upward – CAPE: common variable used to quantify magnitude of instability < 1000: weak 1000-2000: moderate 2000-4000: strong 4000+: extreme Thunderstorms Thunderstorms • Moisture + Instability + Lift = Thunderstorms • What kind of thunderstorms? – Single Cell – Multicell/Squall Line – Supercells Thunderstorm Types • What determines T-storm Type? – Short/simplistic answer: CAPE vs Shear Thunderstorm Types • What determines T-storm Type? (Longer/more complex answer) – Lot we don’t know, other factors (besides CAPE/shear) include • Strength of forcing • Strength of CAP • Shear WRT to boundary • Other stuff Thunderstorm Types • Multi-cell squall lines most common type of severe thunderstorm type locally • Most common type of severe weather is damaging winds • Hail and brief tornadoes can occur with most the intense squall lines Squall Lines & Spotting Squall Line Terminology • Squall Line : a relatively narrow line of thunderstorms, often -

Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....……………

MAY 2006 VOLUME 48 NUMBER 5 SSTORMTORM DDATAATA AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION noaa NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE NATIONAL CLIMATIC DATA CENTER, ASHEVILLE, NC Cover: Baseball-to-softball sized hail fell from a supercell just east of Seminole in Gaines County, Texas on May 5, 2006. The supercell also produced 5 tornadoes (4 F0’s 1 F2). No deaths or injuries were reported due to the hail or tornadoes. (Photo courtesy: Matt Jacobs.) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Outstanding Storm of the Month …..…………….….........……..…………..…….…..…..... 4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....……………...........…............ 5 Additions/Corrections.......................................................................................................................... 406 Reference Notes .............……...........................……….........…..……........................................... 427 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Climatic Data Center Editor: William Angel Assistant Editors: Stuart Hinson and Rhonda Herndon STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events -

Probable Maximum Precipitation Estimates, United States East of the 105Th Meridian

HYDROMETEOROLOGICAL REPORT 'N0.53 L D ..... 'C..,p "\ ..u o tM/ 'A1 ws/t.d/M 'b !>"'"'"' , , 1 1 ~, 5 E.~..~t:-west J/.,e; h~ s,J~ ..s, .... ~ ,41'b ~·qto Seasonal Variation of 10-Square-Mile Probable Maximum Precipitation Estimates, United States East of the 105th Meridian ,_ U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, , -- NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOS~HERIC ADMINISI'RATION U.S. NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION - , - Silver Spnng, Md , , Apn11980 U.S. Department of Commerce U.S. Nuclear Regulatory National Oceanic and Atmospheric Commission Administration NUREG/CR-1486 Hydrometeorological Report No. 53 SEASONAL VARIATION OF 10-SQUARE-MILE PROBABLE MAXIMUM PRECIPITATION ESTIMATES) UNITED STATES EAST OF THE 105TH MERIDIAN Prepared by Francis P. Ho and John T. Riedel Hydrometeorological Branch Office of Hydrology National Weather Service Washington, D.C. April 1980 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract. 1 1. Introduction . 1 1.1 Authorization. 1 1.2 Purpose. 1 1.3 Scope ••... 1 1.4 Definitions .. 2 1.5 Previous study 2 2. Basic data . 2 2.1 Background • • • • • . 2 2.2 Available station rainfall data •• 3 2.2.1 Storm rainfall • • • • • 3 2.2.2 Maximum 1-day or 24-hour values, each month ••••••• 3 2.2.3 Maximum 6-, 12- and 24-hr values, each month . 3 2.2.4 11aximum recorded rainfall at first-order stations. 3 2.2.5 Data tapes, selected stations. 3 2.2.6 Data tapes, 1948-73 •. 5 2.2.7 Canadian data. 5 3. Approach to PMP. • ••. 5 3.1 Summary. 5 3.2 Selected major storm values •. 5 3.3 Moisture maximization. -

A Preliminary Investigation of Derecho

7.A.1 TROPICAL CYCLONE TORNADOES – A RESEARCH AND FORECASTING OVERVIEW. PART 1: CLIMATOLOGIES, DISTRIBUTION AND FORECAST CONCEPTS Roger Edwards Storm Prediction Center, Norman, OK 1. INTRODUCTION those aspects of the remainder of the preliminary article Tropical cyclone (TC) tornadoes represent a relatively that was not included in this conference preprint, for small subset of total tornado reports, but garner space considerations. specialized attention in applied research and operational forecasting because of their distinctive origin within the envelope of either a landfalling or remnant TC. As with 2. CLIMATOLOGIES and DISTRIBUTION PATTERNS midlatitude weather systems, the predominant vehicle for tornadogenesis in TCs appears to be the supercell, a. Individual TCs and classifications particularly with regard to significant1 events. From a framework of ingredients-based forecasting of severe TC tornado climatologies are strongly influenced by the local storms (e.g., Doswell 1987, Johns and Doswell prolificacy of reports with several exceptional events. 1992), supercells in TCs share with their midlatitude The general increase in TC tornado reports, noted as relatives the fundamental environmental elements of long ago as Hill et al. (1966), and in the occurrence of sufficient moisture, instability, lift and vertical wind “outbreaks” of 20 or more per TC (Curtis 2004) probably shear. Many of the same processes – including those is a TC-specific reflection of the recent major increase in involving baroclinicity at various scales – appear -

The Population Bias of Severe Weather Reports West of the Continental Divide

THE POPULATION BIAS OF SEVERE WEATHER REPORTS WEST OF THE CONTINENTAL DIVIDE Paul Frisbie NOAAlNational Weather Service Weather Forecast Office Grand Junction, Colorado Abstract and had 'significant consequences. Lightning from thun derstorms that afternoon sparked the Marble Cone fire Many severe storms in the West may go unreported or (several miles south of Camp Pico Blanco) that burned unobserved, and therefore, the severe weather climatology 177,866 acres - the third largest wildfire in California's is not fully understood. However, as the population has history (California Department of Forestry and Fire increased in the West, so has the number of severe weath Protection 2004). er reports. To check if a population bias exists, correlation The aforementioned cases illustrate the challenges of coefficients are calculated with respect to population for establishing a relevant severe weather climatology for tornadic and nontornadic severe storm activity. The sam the western US. Since no one knows how many severe ple size for tornadic storms is too small to draw any con storms go unreported or unobserved, there is uncertainty clusion. To calculate the correlation coefficients for non regarding the number of severe storms that actually do tornadic severe storms, population and severe weather occur. People have been gradually moving into areas that data are used for every county in each western state were once unpopulated, and are now observing severe between the years 1986-1995 and 1996-2004. The calcu storms that would not have been observed beforehand. To lated correlation coefficients reveal that population and provide a better understanding of how often severe the number ofnontornadic severe storms are significantly weather occurs, trends for tornadic and nontornadic correlated which indicates that a population bias does severe storms will be examined. -

A 10-Year Radar-Based Climatology of Mesoscale Convective System Archetypes and Derechos in Poland

AUGUST 2020 S U R O W I E C K I A N D T A S Z A R E K 3471 A 10-Year Radar-Based Climatology of Mesoscale Convective System Archetypes and Derechos in Poland ARTUR SUROWIECKI Department of Climatology, University of Warsaw, and Skywarn Poland, Warsaw, Poland MATEUSZ TASZAREK Department of Meteorology and Climatology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan, Poland, and National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma, and Skywarn Poland, Warsaw, Poland (Manuscript received 29 December 2019, in final form 3 May 2020) ABSTRACT In this study, a 10-yr (2008–17) radar-based mesoscale convective system (MCS) and derecho climatology for Poland is presented. This is one of the first attempts of a European country to investigate morphological and precipitation archetypes of MCSs as prior studies were mostly based on satellite data. Despite its ubiquity and significance for society, economy, agriculture, and water availability, little is known about the climatological aspects of MCSs over central Europe. Our results indicate that MCSs are not rare in Poland as an annual mean of 77 MCSs and 49 days with MCS can be depicted for Poland. Their lifetime ranges typically from 3 to 6 h, with initiation time around the afternoon hours (1200–1400 UTC) and dissipation stage in the evening (1900–2000 UTC). The most frequent morphological type of MCSs is a broken line (58% of cases), then areal/cluster (25%), and then quasi- linear convective systems (QLCS; 17%), which are usually associated with a bow echo (72% of QLCS). QLCS are the feature with the longest life cycle. -

Template for Electronic Journal of Severe Storms Meteorology

Lyza, A. W., A. W. Clayton, K. R. Knupp, E. Lenning, M. T. Friedlein, R. Castro, and E. S. Bentley, 2017: Analysis of mesovortex characteristics, behavior, and interactions during the second 30 June‒1 July 2014 midwestern derecho event. Electronic J. Severe Storms Meteor., 12 (2), 1–33. Analysis of Mesovortex Characteristics, Behavior, and Interactions during the Second 30 June‒1 July 2014 Midwestern Derecho Event ANTHONY W. LYZA, ADAM W. CLAYTON, AND KEVIN R. KNUPP Department of Atmospheric Science, Severe Weather Institute—Radar and Lightning Laboratories University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, Alabama ERIC LENNING, MATTHEW T. FRIEDLEIN, AND RICHARD CASTRO NOAA/National Weather Service, Romeoville, Illinois EVAN S. BENTLEY NOAA/National Weather Service, Portland, Oregon (Submitted 19 February 2017; in final form 25 August 2017) ABSTRACT A pair of intense, derecho-producing quasi-linear convective systems (QLCSs) impacted northern Illinois and northern Indiana during the evening hours of 30 June through the predawn hours of 1 July 2014. The second QLCS trailed the first one by only 250 km and approximately 3 h, yet produced 29 confirmed tornadoes and numerous areas of nontornadic wind damage estimated to be caused by 30‒40 m s‒1 flow. Much of the damage from the second QLCS was associated with a series of 38 mesovortices, with up to 15 mesovortices ongoing simultaneously. Many complex behaviors were documented in the mesovortices, including: a binary (Fujiwhara) interaction, the splitting of a large mesovortex in two followed by prolific tornado production, cyclic mesovortexgenesis in the remains of a large mesovortex, and a satellite interaction of three small mesovortices around a larger parent mesovortex. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

1 International Approaches to Tornado Damage and Intensity Classification International Association of Wind Engineers

International Approaches to Tornado Damage and Intensity Classification International Association of Wind Engineers (IAWE), International Tornado Working Group 2017 June 6, DRAFT FINAL REPORT 1. Introduction Tornadoes are one of the most destructive natural Hazards on Earth, with occurrences Having been observed on every continent except Antarctica. It is difficult to determine worldwide occurrences, or even the fatalities or losses due to tornadoes, because of a lack of systematic observations and widely varying approacHes. In many jurisdictions, there is not any tracking of losses from severe storms, let alone the details pertaining to tornado intensity. Table 1 provides a summary estimate of tornado occurrence by continent, with details, wHere they are available, for countries or regions Having more than a few observations per year. Because of the lack of systematic identification of tornadoes, the entries in the Table are a mix of verified tornadoes, reports of tornadoes and climatological estimates. Nevertheless, on average, there appear to be more than 1800 tornadoes per year, worldwide, with about 70% of these occurring in North America. It is estimated that Europe is the second most active continent, with more than 240 per year, and Asia third, with more than 130 tornadoes per year on average. Since these numbers are based on observations, there could be a significant number of un-reported tornadoes in regions with low population density (CHeng et al., 2013), not to mention the lack of systematic analysis and reporting, or the complexity of identifying tornadoes that may occur in tropical cyclones. Table 1 also provides information on the approximate annual fatalities, althougH these data are unavailable in many jurisdictions and could be unreliable. -

A Preliminary Investigation of Derecho-Producing Mcss In

P 3.1 TROPICAL CYCLONE TORNADO RECORDS FOR THE MODERNIZED NWS ERA Roger Edwards1 Storm Prediction Center, Norman, OK 1. INTRODUCTION and BACKGROUND since 1954 was attributable to the weakest (F0) bin of damage rating (Fig. 1). This is the very class of Tornadoes from tropical cyclones (hereafter TCs) tornado that is most common in TC records, and most pose a specialized forecast challenge at time scales difficult to detect in the damage above that from the ranging from days for outlooks to minutes for concurrent or subsequent passage of similarly warnings (Spratt et al. 1997, Edwards 1998, destructive, ambient TC winds. As such, it is possible Schneider and Sharp 2007, Edwards 2008). The (but not quantifiable) that many TC tornadoes have fundamental conceptual and physical tenets of gone unrecorded even in the modern NWS era, due midlatitude supercell prediction, in an ingredients- to their generally ephemeral nature, logistical based framework (e.g., Doswell 1987, Johns and difficulties of visual confirmation, presence of swaths Doswell 1992), fully apply to TC supercells; however, of sparsely populated near-coastal areas (i.e., systematic differences in the relative magnitudes of marshes, swamps and dense forests), and the moisture, instability, lift and shear in TCs (e.g., presence of damage inducers of potentially equal or McCaul 1991) contribute strongly to that challenge. greater impact within the TC envelope. Further, there is a growing realization that some TC tornadoes are not necessarily supercellular in origin (Edwards et al. 2010, this volume). Several major TC tornado climatologies have been published since the 1960s (e.g., Pearson and Sadowski 1965, Hill et al. -

Storms Are Thunderstorms That Produce Tornadoes, Large Hail Or Are Accompanied by High Winds

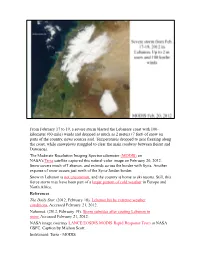

From February 17 to 19, a severe storm blasted the Lebanese coast with 100- kilometer (60-mile) winds and dropped as much as 2 meters (7 feet) of snow on parts of the country, news sources said. Temperatures dropped to near freezing along the coast, while snowplows struggled to clear the main roadway between Beirut and Damascus. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this natural-color image on February 20, 2012. Snow covers much of Lebanon, and extends across the border with Syria. Another expanse of snow occurs just north of the Syria-Jordan border. Snow in Lebanon is not uncommon, and the country is home to ski resorts. Still, this fierce storm may have been part of a larger pattern of cold weather in Europe and North Africa. References The Daily Star. (2012, February 18). Lebanon hit by extreme weather conditions. Accessed February 21, 2012. Naharnet. (2012, February 19). Storm subsides after coating Lebanon in snow. Accessed February 21, 2012. NASA image courtesy LANCE/EOSDIS MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. Caption by Michon Scott. Instrument: Terra - MODIS Flooding is the most common of all natural hazards. Each year, more deaths are caused by flooding than any other thunderstorm related hazard. We think this is because people tend to underestimate the force and power of water. Six inches of fast-moving water can knock you off your feet. Water 24 inches deep can carry away most automobiles. Nearly half of all flash flood deaths occur in automobiles as they are swept downstream.