A People's Budget

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 543 Union Street #1E Brooklyn, NY 11215 718.541.4378 GOWANUS CANAL CONSERVANCY 2015 ANNUAL REPORT Dear Friends, Partners and Members

2015 ANNUAL REPORT 543 Union Street #1E Brooklyn, NY 11215 718.541.4378 GOWANUS CANAL CONSERVANCY 2015 ANNUAL REPORT Dear Friends, Partners and Members, Since its inception, the Conservancy has advocated for an open space network that would support and protect the health of the Gowanus Canal while providing access to its shores and vibrant public parks and corridors for the people who live, work and play in the neighborhood. In 2015, that vision started to become a reality. Construction began on the Sponge Park, which will transform the end of 2nd Street into a canal-fronting park that captures and filters stormwater. Additionally, as plans for new development and Superfund-related infrastructure emerge on the north end of the canal, it is clear that better (and more) public space is a priority, particularly along the canal’s edge. As these projects unfold, we are working closely with diverse local partners like Fifth Avenue Committee, Gowanus Alliance, Arts Gowanus, Old Stone House and others to ensure that these emerging public spaces not only reflect the community’s interests, priorities and needs, but weave together into an interconnected Greenscape, maximizing the health, resiliency, vibrancy and beauty of our Gowanus neighborhood. Throughout the next year, we will continue to reach out to residents, businesses and partners to get your input on the priorities for the Greenscape, with an eye toward designing a community-based masterplan that reflects the unique qualities of Gowanus. To learn more about the Greenscape initiative and how you can help, please visit our website www. gowanuscanalconservancy.org. We not only welcome your input, we need it! Ben Jones Board Chair LETTER FROM THE CHAIR SMITH ST ATLANTIC AVE GOWANUS WATERSHED PROSPECT PARK We envision the evolution of an Open, Clean and Alive Gowanus Canal and Watershed with accessible, connective open space; clean water, soil and air; and vibrant ecological, business and cultural activity. -

New York City Council Environmental SCORECARD 2017

New York City Council Environmental SCORECARD 2017 NEW YORK LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS nylcv.org/nycscorecard INTRODUCTION Each year, the New York League of Conservation Voters improve energy efficiency, and to better prepare the lays out a policy agenda for New York City, with goals city for severe weather. we expect the Mayor and NYC Council to accomplish over the course of the proceeding year. Our primary Last month, Corey Johnson was selected by his tool for holding council members accountable for colleagues as her successor. Over the years he has progress on these goals year after year is our annual been an effective advocate in the fight against climate New York City Council Environmental Scorecard. change and in protecting the health of our most vulnerable. In particular, we appreciate his efforts In consultation with over forty respected as the lead sponsor on legislation to require the environmental, public health, transportation, parks, Department of Mental Health and Hygiene to conduct and environmental justice organizations, we released an annual community air quality survey, an important a list of eleven bills that would be scored in early tool in identifying the sources of air pollution -- such December. A handful of our selections reward council as building emissions or truck traffic -- particularly members for positive votes on the most significant in environmental justice communities. Based on this environmental legislation of the previous year. record and after he earned a perfect 100 on our City The remainder of the scored bills require council Council Scorecard in each year of his first term, NYLCV members to take a public position on a number of our was proud to endorse him for re-election last year. -

NYC Council District 45 (Flatbush, East Flatbush, Flatlands, Midwood, Canarsie)

NYC Council District 45 (Flatbush, East Flatbush, Flatlands, Midwood, Canarsie) Monique Chandler-Waterman P. 3 Farah Louis P. 9 Xamayla Rose P. 15 Anthony Beckford * P. 21 * Anthony Beckford is no longer running in the May 14, 2019 Special Election and will not appear on the ballot. NYC Council District 45 Special Election Questionnaire About Us Launched in 2017, Voters For Animal Rights (VFAR) is a New York based 501c(4) grassroots multi-issue animal advocacy organization that is building political power for animals. Our mission is to elect candidates who support animal protection, lobby for stronger laws to stop animal cruelty, and hold elected officials accountable to humane voters. VFAR mobilizes public concern for animals through the political process. We know that animal protection is not only a moral issue but a bi-partisan political issue as well. Over 90% of Americans believe that animals need protection from abuse and exploitation. To that end, we organize humane voters to support candidates that care about animals. If you support animals, then we want to support you! There are over 60,000 humane voters throughout New York state, hundreds of which are volunteers for VFAR who are ready to knock on doors, make phone calls and get out the vote to elect people that will stand up for animals. We deliver the vote – for the animals and for you. As an example, here is our animal-friendly voter guide from the NYC Special Election for Public Advocate. Endorsement Process Candidates seeking our endorsement for the NYC Council District 45 Special Election are required to fill out this questionnaire and submit to [email protected] by Friday, April 26. -

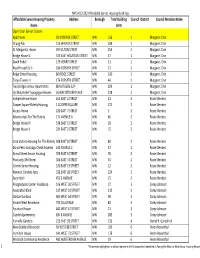

Master 202 Property Profile with Council Member District Final For

NYC HUD 202 Affordable Senior Housing Buildings Affordable Senior Housing Property Address Borough Total Building Council District Council Member Name Name Units Open Door Senior Citizens Apartment 50 NORFOLK STREET MN 156 1 Margaret Chin Chung Pak 125 WALKER STREET MN 104 1 Margaret Chin St. Margarets House 49 FULTON STREET MN 254 1 Margaret Chin Bridge House VI 323 EAST HOUSTON STREET MN 17 1 Margaret Chin David Podell 179 HENRY STREET MN 51 1 Margaret Chin Nysd Forsyth St Ii 184 FORSYTH STREET MN 21 1 Margaret Chin Ridge Street Housing 80 RIDGE STREET MN 100 1 Margaret Chin Tanya Towers II 174 FORSYTH STREET MN 40 1 Margaret Chin Two Bridges Senior Apartments 80 RUTGERS SLIP MN 109 1 Margaret Chin Ujc Bialystoker Synagogue Houses 16 BIALYSTOKER PLACE MN 128 1 Margaret Chin Independence House 165 EAST 2 STREET MN 21 2 Rosie Mendez Cooper Square Elderly Housing 1 COOPER SQUARE MN 151 2 Rosie Mendez Access House 220 EAST 7 STREET MN 5 2 Rosie Mendez Alliance Apts For The Elderly 174 AVENUE A MN 46 2 Rosie Mendez Bridge House IV 538 EAST 6 STREET MN 18 2 Rosie Mendez Bridge House V 234 EAST 2 STREET MN 15 2 Rosie Mendez Casa Victoria Housing For The Elderly 308 EAST 8 STREET MN 80 2 Rosie Mendez Dona Petra Santiago Check Address 143 AVENUE C MN 57 2 Rosie Mendez Grand Street Senior Housing 709 EAST 6 STREET MN 78 2 Rosie Mendez Positively 3Rd Street 306 EAST 3 STREET MN 53 2 Rosie Mendez Cabrini Senior Housing 220 EAST 19 STREET MN 12 2 Rosie Mendez Renwick Gardens Apts 332 EAST 28 STREET MN 224 2 Rosie Mendez Securitad I 451 3 AVENUE MN 15 2 Rosie Mendez Postgraduate Center Residence 516 WEST 50 STREET MN 22 3 Corey Johnson Associated Blind 137 WEST 23 STREET MN 210 3 Corey Johnson Clinton Gardens 404 WEST 54 STREET MN 99 3 Corey Johnson Encore West Residence 755 10 AVENUE MN 85 3 Corey Johnson Fountain House 441 WEST 47 STREET MN 21 3 Corey Johnson Capitol Apartments 834 8 AVENUE MN 285 3 Corey Johnson Yorkville Gardens 225 EAST 93 STREET MN 133 4 Daniel R. -

DAVID I. WEPRIN Reports to the Community Winter 2018

Assemblymember DAVID I. WEPRIN Reports to the Community Winter 2018 Serving the partial or entire communities of: Briarwood, Bellerose, Bellerose Manor, Fresh Meadows, Glen Oaks, Hillcrest, Hollis Hills, Holliswood, Jamaica Estates, Jamaica Hills, Oakland Gardens, Queens Village, Richmond Hill, South Richmond Hill, and Utopia. A Message From STANDING UP FOR IMMIGRANTS DAVID I. WEPRIN Dear Friends and Neighbors, I want to wish Happy Holidays to you and your Assemblyman David Weprin,Chair of the NYS Assembly Committee families this on Correction, calls for the end of the unconstitutional indefinite joyous season. detention of immigrants in New York State jails with immigration advocates. We are fortunate to celebrate a Assemblyman David I. Weprin, Chair of the NYS Assembly Committee on Correction, joined the New York Immigration multitude of different Coalition, Legal Action Center, Chhaya CDC, affected family holidays and live in harmony with our diverse members, and others at the ICE Varick Street Detention Facility neighbors in Queens. As New Yorkers, we stand to call on U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) out as a model of peaceful coexistence for the and the United States Department of Justice (USDOJ) to end the nation. We have shown that working together indefinite detentions of asylum seekers and other immigrants we can continue to build a strong and safe being held on administrative violations. There have been several instances where undocumented immigrants and asylum seek- community. ers have been held for extended periods while awaiting court As the cold weather approaches, I urge proceedings or additional instructions; despite either having demonstrated a credible fear and being deemed eligible for asy- everyone to stay warm and safe. -

Haitians Rally in Times Square Against Trump Caribbean Countries Express Outrage Over US Prez's Insults

FREE www.caribbeanlifenews.com QUEENS/LONG ISLAND/BRONX/MANHATTAN Jan. 19–Jan. 25, 2018 CARICOM TRASHES TRUMP Caribbean countries express outrage over US prez’s insults By Bert Wilkinson cifically. In the past week, Caribbean After all, Haiti is a full mem- community governments have ber of the group of 15 nations. been forced to grapple with two It was the last to join at a sum- major issues of international mit in Guyana in 2002, large- concern and of course one had to ly through the extra efforts of do with the outrageous remarks then Jamaican Prime Minister by President Trump about Haiti, P. J Patterson African immigrants and a pref- The leaders said in their erence for the lily white peo- angry narrative on Trump’s ple from Norway settling in the remarks that he has “this pat- United States. tern of denigrating Haiti and When Trump had made the its citizens in what seems to racist statements to a biparti- be a concerted attempt to per- Many demonstrators paralleled the head of state’s comments with white surpremacist san group of congress men and petuate a negative narrative of language. Community News Group / Alexandra Simon women at a White House meet- the country. We are especially ing, many in the Caribbean saddened that such narrative began listening for some form emerged around the time of the of formal and official reaction anniversary of the devastating Haitians rally in Times Square against Trump from leaders in the region. They 2010 earthquake which took so reasoned that they should be so many lives of citizens in that By Alexandra Simon with the President’s com- Johnson. -

June 15, 2020 Mayor Bill De Blasio City Hall New York, NY

ENJAMIN ALLOS CHAIR B J. K Contracts COUNCIL MEMBER, 5TH DISTRICT CO-CHAIR 244 East 93rd Street Progressive Caucus New York, NY 10128 (212) 860-1950 Voice COMMITTEES (212) 980-1828 Fax Education www.BenKallos.com Governmental Operations THE COUNCIL OF THE Oversight & Investigations [email protected] Women & Gender Equity CITY OF NEW YORK June 15, 2020 Mayor Bill de Blasio City Hall New York, NY 10007 Dear Mayor de Blasio; As we face unprecedented times and a budget that must-see painful cuts, we should look for possible waste and opportunities for revenues and savings. I have proposed $15.24 billion in potential savings and revenue for our city’s budget in order to invest $827 million in spending on programs that support children, families, seniors, and our planet that will reduce costs and generate revenues. In 2014, we inherited a $68.5 billion expense budget that has since grown by more than 30% to $92.8 billion. Surely in this $24.3 billion in growth we can find opportunities for cost savings, as we also reexamine the initial $68.5 billion, we inherited. As a city we must seek capital savings, find ways to significantly and responsibly reduce the NYPD budget, and examine clawing back real property tax exemptions, cancelling irresponsible contracts, and maintaining spending for programs that avoid costs and generate revenue. The city’s budget must continue to reflect our values by investing in our youth, families, and seniors. We must maintain summer programs (summer youth employment & summer SONYC), expand 3-K, reopen parks and beaches, and provide seniors the support they need through their local senior centers. -

A Pdf of This Release Is Available to Download

Contact: Natasha Burns Director of Marketing and Communications ACEC New York Phone: (518) 452-8611 [email protected] ACEC NEW YORK ANNOUNCES 2017 ENDORSEMENTS FOR NEW YORK CITY NEW YORK, August 30, 2017 -- The Political Action Committee of the American Council of Engineering Companies of New York (ACEC New York) – the voice of the consulting engineering industry – announced today its list of endorsements for New York City’s 2017 elections. Founded in 1921, ACEC New York represents over 270 member firms throughout New York State that collectively employ close to 25,000 people, with a concentrated presence of firms located in New York City, whose members engage in every discipline of engineering related to the built environment including civil, structural, mechanical, electrical, environmental, and geotechnical fields. The ACEC New York City PAC endorses the following: Office Candidate Office Candidate City Council – District 1 Margaret S. Chin City Council – District 22 Costa G. Constantinides City Council – District 2 Carlina Rivera City Council – District 23 Barry S. Grodenchik City Council – District 5 Ben Kallos City Council – District 28 Adrienne Adams City Council – District 6 Helen K. Rosenthal City Council – District 30 Elizabeth S. Crowley City Council – District 7 Mark Levine City Council – District 31 Donovan J. Richards City Council – District 10 Ydanis Rodríguez City Council – District 37 Rafael L. Espinal, Jr. City Council – District 17 Rafael Salamanca, Jr. City Council – District 39 Bradford Lander City Council – District 19 Paul A. Vallone City Council – District 44 Kalman Yeger City Council – District 20 Peter Koo City Council – District 47 Mark Treyger Comptroller Scott M. -

Reform Party

Statement and Return Report for Certification Primary Election 2018 - 09/13/2018 Kings County - Reform Party Reform Attorney General Citywide Vote for 1 Page 1 of 17 BOARD OF ELECTIONS Statement and Return Report for Certification IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK Primary Election 2018 - 09/13/2018 PRINTED AS OF: Kings County 9/27/2018 12:08:48PM Reform Party Reform Attorney General (Citywide), vote for 1 Assembly District 41 PUBLIC COUNTER 153 MANUALLY COUNTED EMERGENCY 0 ABSENTEE / MILITARY 7 AFFIDAVIT 0 Total Ballots 160 Less - Inapplicable Federal/Special Presidential Ballots 0 Total Applicable Ballots 160 NANCY B. SLIWA 59 MIKE DIEDERICH 40 CHRISTOPHER B. GARVEY 38 ADELE COHEN (WRITE-IN) 1 ANDREW CUOMO (WRITE-IN) 2 LEECIA EVE (WRITE-IN) 1 LETITIA A. JAMES (WRITE-IN) 5 MAX ROSE (WRITE-IN) 1 SEAN PATRICK MALONEY (WRITE-IN) 1 SIMCHA FELDER (WRITE-IN) 1 UNATTRIBUTABLE WRITE-IN (WRITE-IN) 4 ZEPHYR TEACHOUT (WRITE-IN) 2 Total Votes 155 Unrecorded 5 Assembly District 42 PUBLIC COUNTER 102 MANUALLY COUNTED EMERGENCY 0 ABSENTEE / MILITARY 4 AFFIDAVIT 1 Total Ballots 107 Less - Inapplicable Federal/Special Presidential Ballots 0 Total Applicable Ballots 107 NANCY B. SLIWA 43 MIKE DIEDERICH 18 CHRISTOPHER B. GARVEY 21 CYNTHIA NIXON (WRITE-IN) 1 GEDALYA WIELGUS (WRITE-IN) 1 LETITIA A. JAMES (WRITE-IN) 7 ROSS PERA (WRITE-IN) 1 SEAN PATRICK MALONEY (WRITE-IN) 1 SIMCHA FELDER (WRITE-IN) 1 UNATTRIBUTABLE WRITE-IN (WRITE-IN) 2 ZEPHYR TEACHOUT (WRITE-IN) 3 Total Votes 99 Unrecorded 8 Page 2 of 17 BOARD OF ELECTIONS Statement and Return Report for Certification IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK Primary Election 2018 - 09/13/2018 PRINTED AS OF: Kings County 9/27/2018 12:08:48PM Reform Party Reform Attorney General (Citywide), vote for 1 Assembly District 43 PUBLIC COUNTER 173 MANUALLY COUNTED EMERGENCY 0 ABSENTEE / MILITARY 11 AFFIDAVIT 0 Total Ballots 184 Less - Inapplicable Federal/Special Presidential Ballots 0 Total Applicable Ballots 184 NANCY B. -

New York Legislators Call on Cuny Administration to Stop Cuts and Layoffs

NEW YORK LEGISLATORS CALL ON CUNY ADMINISTRATION TO STOP CUTS AND LAYOFFS May 27, 2020 William C. Thompson, Jr. Chairperson, Board of Trustees The City University of New York Félix V. Matos Rodríguez Chancellor, The City University of New York 205 East 42nd Street New York, NY 10017 Dear Chairperson Thompson and Chancellor Matos Rodríguez: We write as elected officials of New York City and New York State who strongly support The City University of New York. We want to express our concern about plans announced by CUNY colleges to lay off hundreds of adjunct faculty by May 29 and cut course offerings for the fall by as much as 35 percent. New York will need CUNY more than ever as we seek to rebuild the economy. The communities that have borne the greatest loss of life and employment during the pandemic are exactly the communities whose members rely on CUNY and who will turn to CUNY to rebuild their lives. New Yorkers from all parts of the city and surrounding region will need CUNY as they seek to gain new skills and earn college degrees. Reduced course offerings, fewer faculty and over-sized classes will leave CUNY under-prepared to support the students whose need for support is greatest. A strong and fully staffed CUNY is a unique and essential resource for New York’s recovery. While we are painfully aware of the budgetary crisis facing the City and State, we believe that the CUNY administration should pursue every alternative before reducing course offerings and enacting mass layoffs. The CARES Act allocated more than $100 million to CUNY for institutional support during the crisis, with an explicit provision about keeping employees on payroll. -

The Geography—And New Politics—Of Housing in New York City Public Housing

The Geography—and New Politics—of Housing in New York City Public Housing Tom Waters, Community Service Society of New York, November 2018 The 178,000 public housing apartments owned and operated by the New York City Housing Authority are often de- scribed as “a city within a city.” The Community Service Society has estimated the numbers of public housing apartments for the New York City portion of each legislative district in the city. These estimates were made by assigning buildings within public housing developments to legislative districts based on their addresses. United States Congress District U.S. Representative Public Housing 13 Adriano Espaillat 34,180 8 Hakeem Jeffries 33,280 15 José Serrano 32,210 7 Nydia Velazquez 26,340 12 Carolyn Maloney 10,290 9 Yvette Clarke 9,740 11 Max Rose 6,130 5 Gregory Meeks 5,980 10 Jerrold Nadler 5,530 14 Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez 5,500 16 Eliot Engel 4,630 6 Grace Meng 3,410 3 Tom Suozzi 0 New York State Senate District Senator Public Housing 30 Brian Benjamin 28,330 25 Velmanette Montgomery 16,690 32 Luis Sepúlveda 16,590 19 Roxanne J. Persaud 14,570 29 José M. Serrano 13,920 Learn more at www.cssny.org/housinggeography Community Service Society New York State Senate (cont.) District Senator Public Housing 18 Julia Salazar 13,650 26 Brian Kavanagh 12,020 23 Diane J. Savino 9,220 20 Zellnor Myrie 7,100 12 Michael Gianaris 6,420 33 Gustavo Rivera 5,930 36 Jamaal Bailey 5,510 31 Robert Jackson 5,090 10 James Sanders Jr. -

Candidate Questionnaire

2013 QUESTIONNAIRE FOR CANDIDATES FOR CITY COUNCIL Citizens Union would appreciate your response to the following questions related to policy issues facing the City of New York that are of concern to Citizens Union and residents of the City. We plan to make public your responses to this questionnaire in our Voters Directory, on our website, and in other appropriate venues. Responses to these questions will be one of several factors Citizens Union will use to evaluate candidates who are running for office in order to determine our "Preferred Candidates" for the primary election and "Endorsed Candidates" for the general election. If you seek our support, we would also need to schedule an interview with you as part of the evaluation process. We will not automatically schedule an interview with you if you return this questionnaire, as we prioritize competitive races and resources constrain us from evaluating all races. Please contact us if you wish to be interviewed. We thank you very much for your response. Candidate Name:Carlos Menchaca Age:32 Campaign Address: 4413 sth Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11220 Campaign Telephone Number: (718) 851-2681 Party Affiliation(s): Democrat and Working Families Campaign Manager Name: lvan Luevanos Website & Email: www.carlos*013.*om & carlos@carlos201 3.com Education: Jesuit University of San Francisco, Bachelor of Arts, Politics Bachelor of Arts, Performing Arts and Social Justice Occupation/Employer (or years in currently held elected office): City Council Candidate Previous Off ices, Cam palg ns and Com m u nity/Civic I nvolvement: -LGBT & HIV/AIDS Community Liaison Office of the Speaker of the New York City Council, Christine C.