Spatial and Temporal Processes Within Improvisational Tribal Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Come Celebrate the 15Th Year Aniversary of the Alameda Point Antiques Faire

The Official Faire Magazine and Program Guide FREE! Volume 4 Issue 9 SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 2, 2012 come early for the faire and stay for the auction! Visit Our Website to Discover How to Shop the Faire 365 days a Year MICHAAN’S AUCTIONS PRESENTS Come Celebrate the 15th Year Aniversary of The Alameda Point Antiques Faire Details Inside! • Detailed Booth Maps for Antiques Faire • Additional Maps with Alternate • Partial Sellers Directories Routes to Freeways • Details About Our Rain-Out Policy • Fun and Informative Articles Antiques By The Bay, Inc. • 510-522-7500 Michaan’s auctions • 510-740-0220 www.alamedapointantiquesfaire.com www.michaans.com 2900SEPTEMBER Navy Way 2, (at 2012 Main Street) Alameda, CA 94510 2751 Todd Street, Alameda, CA 94501 1 Michaan’s Auctions presents Now Accepting Quality Consignments for our Upcoming Auctions. We are looking for consignments of fine art, American and European furniture, decorations, Asian art, fine jewelry and timepieces for our auctions. To schedule a private appointment or to inquire about consigning please contact Tammie Chambless at (510) 227-2530. 1. Hermann Herzog (American 1832-1932) Farallon Islands, Pacific Coast Sold for $43,875 2. A Finely Carved Rhinoceros Horn ‘Lotus’ Libation Cup, 17th/18th Century Sold for $70,200 3. Philip & Kelvin LaVerne Studios Chan Coffee Table Sold for $6,435 Ph. (800) 380-9822 • (510) 740-0220 2751 Todd Street, Alameda, California 94501 Bond #70044066 Michaan’s Auctions presents The Official Magazine and Program Guide of the Alameda Point Antiques Faire * The Alameda Point Antiques Faire and Alameda Point Vintage Fashion Faire are not affiliated with any other antique shows. -

BCCA Programs 2021-22

T H E 2 0 2 1 / 2 2 S E A S O N DANCE IN THE CREEK @ B R A G G C R E E K C O M M U N I T Y A S S O C I A T I O N We offer a variety of recreational programs at BCCA, each running on a short 4-month basis! Our classes in Bragg Creek are focused on building community, confidence, and keeping kids active and engaged! "SO MUCH MORE O U R B C C A P R O G R A M S ( E N C L O S E D ) : THAN DANCE" O U R P H I L O S O P H Y . CREATIVE MOVEMENT CLASSES FOR AGE 3-4 We strongly believe in creating opportunities and experiences that go beyond dance steps. While we are proud of the level of instruction and training we provide, "FUSION" CLASSES FOR we believe strongly in "human before dancer." From the AGE 5-6 interactions we have, to the values we embrace, and the culture we promote, our programs are about much more TUITION RATES & PACKAGES than dance, especially in Bragg Creek... CREATIVE MOVEMENT & PRE-JUNIOR DATES, RATES, & INCLUSIONS F O R A G E 3 - 6 Classes and schedule: "Tiny Ballerinas" for AGE 3-4 - Mondays, 9:15-9:45am "Hop n' Pop" for AGE 3-4 - Mondays, 9:50-10:20am "Tumble Tykes" for AGE 3-4 - 10:30-11:00am "Fusion" Dance for AGE 4-5 - 12:00-12:45pm "Fusion" Dance for AGE 4-5 - 2:45-3:30pm Pre-Junior "Fusion" for AGE 5-6 - Mondays, 3:30-4:15pm Dates: September 13th to December 13th (NO classes Oct. -

Belly Dancing in New Zealand

BELLY DANCING IN NEW ZEALAND: IDENTITY, HYBRIDITY, TRANSCULTURE A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Cultural Studies in the University of Canterbury by Brigid Kelly 2008 Abstract This thesis explores ways in which some New Zealanders draw on and negotiate both belly dancing and local cultural norms to construct multiple local and global identities. Drawing upon discourse analysis, post-structuralist and post-colonial theory, it argues that belly dancing outside its cultures of origin has become globalised, with its own synthetic culture arising from complex networks of activities, objects and texts focused around the act of belly dancing. This is demonstrated through analysis of New Zealand newspaper accounts, interviews, focus group discussion, the Oasis Dance Camp belly dance event in Tongariro and the work of fusion belly dance troupe Kiwi Iwi in Christchurch. Bringing New Zealand into the field of belly dance study can offer deeper insights into the processes of globalisation and hybridity, and offers possibilities for examination of the variety of ways in which belly dance is practiced around the world. The thesis fills a gap in the literature about ‘Western’ understandings and uses of the dance, which has thus far heavily emphasised the United States and notions of performing as an ‘exotic Other’. It also shifts away from a sole focus on representation to analyse participants’ experiences of belly dance as dance, rather than only as performative play. The talk of the belly dancers involved in this research demonstrates the complex and contradictory ways in which they articulate ideas about New Zealand identities and cultural conventions. -

Community Programs

| Dance Staff Community Programs Alicia Cross Engelhardt Director & Tap Dance Isabella Dallas Ballet Cindi Adkins Belly Dance Lola Pittenger Zumba-Yoga en Español Maria Bautista Baile Folklórico Teeny Ballereenies Dance with Me Ja Nelle Pleasure Contemporary & Fusion Saturdays, 10:15-10:45am Phillips Recreation Center Enroll in more two or more dance classes in a Age 2 with Guardian season and GET A $5 DISCOUNT on the second Teeny Ballereenies Dance with Me is a fun place to enter the class. Only available when enrolling in person wonderful world of dance and movement. Your child will be or by phone at 217-367-1544. introduced to the music and the movement of ballet with fun exercises perfect for adventurous and imaginative little ones. Adults participate along with the Ballereenies to give them the confidence Bigger Ballereenies and one-on-one support that they need. Date EB Cost | Deadline Cost | Deadline Code Saturdays, 1:15-2pm Jan 21-Feb 25 $40R/$60NR | Jan 7 $48R/$72NR | Jan 14 4706 Phillips Recreation Center Mar 4-Apr 8 $40R/$60NR | Feb 18 $48R/$72NR | Feb 25 4707 Ages 5-6 This program is for those who have completed Teeny Ballereenies or the equivalent and are ready to learn some new ballet skills. You Teeny Ballereenies are welcome to quietly observe your child in class. Saturdays, 11-11:30am (Ages 3-4) or 9:15-10am (Ages 4-5) Phillips Recreation Center Date EB Cost | Deadline Cost | Deadline Code Jan 21-Feb 25 $40R/$60NR | Jan 7 $48R/$72NR | Jan 14 4700 Introduce your young dancer to the music and the movement Mar 4-Apr 8 $40R/$60NR | Feb 18 $48R/$72NR | Feb 25 4701 of ballet with fun exercises perfect for little ones. -

The World Atlas of Musical Instruments

Musik_001-004_GB 15.03.2012 16:33 Uhr Seite 3 (5. Farbe Textschwarz Auszug) The World Atlas of Musical Instruments Illustrations Anton Radevsky Text Bozhidar Abrashev & Vladimir Gadjev Design Krassimira Despotova 8 THE CLASSIFICATION OF INSTRUMENTS THE STUDY OF MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS, their history, evolution, construction, and systematics is the subject of the science of organology. Its subject matter is enormous, covering practically the entire history of humankind and includes all cultural periods and civilizations. The science studies archaeological findings, the collections of ethnography museums, historical, religious and literary sources, paintings, drawings, and sculpture. Organology is indispensable for the development of specialized museum and amateur collections of musical instruments. It is also the science that analyzes the works of the greatest instrument makers and their schools in historical, technological, and aesthetic terms. The classification of instruments used for the creation and performance of music dates back to ancient times. In ancient Greece, for example, they were divided into two main groups: blown and struck. All stringed instruments belonged to the latter group, as the strings were “struck” with fingers or a plectrum. Around the second century B. C., a separate string group was established, and these instruments quickly acquired a leading role. A more detailed classification of the three groups – wind, percussion, and strings – soon became popular. At about the same time in China, instrument classification was based on the principles of the country’s religion and philosophy. Instruments were divided into eight groups depending on the quality of the sound and on the material of which they were made: metal, stone, clay, skin, silk, wood, gourd, and bamboo. -

Music in the World of Islam a Socio-Cultural Study

Music in the World of Islam A Socio-cultural study Arnnon Shiloah C OlAR SPRESS © Arnnon Shiloah, 1995 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise withoııt the prior permission of the pııb lisher. Published in Great Britain by Scolar Press GowerHouse Croft Road Aldershat Hants GUll 31-IR England British Library Cataloguing in Pııblication Data Shiloah, Arnnon Music in the world of Islam: a socio-cultural study I. Title 306.4840917671 ISBN O 85967 961 6 Typeset in Sabon by Raven Typesetters, Chester and printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Guildford Thematic bibliography (references) Abbreviations AcM Acta Musicologica JAMS Journal of the American Musicological Society JbfMVV Jahrbuch für Musikalische Volks- und Völkerkunde JIFMC Journal of the International Fo lk Music Council JRAS Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society RE! Revue des Etudes Islamiques S!Mg Sammelbiinde der In temationale Musikgesellschaft TGUOS Transactions of the Glasgow University Oriental Society YIFMC Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council YFTM Yearbook for Traditional Music ZfMw Zeitschrift für Musikwissenschaft I. Bibliographical works (see also 76) 1. Waterman, R. A., W. Lichtenwanger, V. H. Hermann, 'Bibliography of Asiatic Musics', No tes, V, 1947-8,21, 178,354, 549; VI, 1948-9, 122,281,419, 570; VII, 1949-50,84,265,415, 613; VIII,1950-51, 100,322. 2. Saygun, A., 'Ethnomusicologie turque', AcM, 32, 1960,67-68. 3. Farmer, H. G., The Sources ofArabian Music, Leiden: Brill, 1965. 4. Arseven, V., Bibliography of Books and Essays on Turkish Folk Music, Istanbul, 1969 (in Turkish). -

2 Unlimited Tribal Dance Mp3, Flac, Wma

2 Unlimited Tribal Dance mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Tribal Dance Country: Philippines Released: 1993 Style: Euro House MP3 version RAR size: 1998 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1575 mb WMA version RAR size: 1244 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 839 Other Formats: AU VOC XM MMF ASF DXD MIDI Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Tribal Dance (Ritmo Tribal 7") 3:45 2 Tribal Dance (Extended) 5:15 3 Tribal Dance (Extended Rap) 5:16 Tribal Dance (Automatic African Remix) 4 4:40 Remix – Otto van den Toorn Tribal Dance (Automatic Breakbeat Remix) 5 4:51 Remix – Otto van den Toorn Credits Arranged By [Vocals] – Peter Bauwens Artwork – Fred Van Lé Mixed By, Recorded By, Producer – Phil Wilde Producer, Executive-Producer – Jean-Paul De Coster Notes Spanish Release (inside cover prints 6 tracks from the english versions,the 2 first are rap edit and edit that are not in this 5 tracks edition, instead track 1 is the spanish version) Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: SGAE Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year BYTE 5020, Tribal Dance (CD, Byte Records, BYTE 5020, 2 Unlimited Benelux 1993 181.225.3 Maxi) ToCo International 181.225.3 Tribal Dance PWMC 262 2 Unlimited PWL Continental PWMC 262 UK 1993 (Cass, Single) Tribal Dance (CD, QSPD 750 2 Unlimited Quality Music QSPD 750 Canada 1993 Maxi, Promo) ZYX 7000-12 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance (12") ZYX Music ZYX 7000-12 Germany 1993 Tribal Dance (CD, 01624 15509-2 2 Unlimited Critique 01624 15509-2 US 1993 Maxi) Related Music albums to Tribal Dance by 2 Unlimited 2 Unlimited - No Limits! Tohpati Featuring Jimmy Haslip & Chad Wackerman - Tribal Dance 2 Unlimited - Let The Beat Control Your Body Various - African Tribal Songs Omar Salinas - The Tribal EP 2 Unlimited - The Ultimixx 2 Unlimited - No Limit Tribal Riot - Loco Tribal - Kanta Fallah 2 Unlimited - Greatest Remix Hits. -

Feminist Analysis of Belly Dance and Its Portrayal in the Media

FEMINISM IN BELLY DANCE AND ITS PORTRAYAL IN THE MEDIA Meghana B.S Registered Number 1324038 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Communication Christ University Bengaluru 2015 Program Authorized to Offer Degree Department of Media Studies ii Authorship Christ University Department of Media Studies Declaration This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a master‟s thesis by Meghana B.S Registered Number1324038 and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Committee Members: _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ Date:__________________________________ iii iv Abstract I, Meghana B.S, confirm that this dissertation and the work presented in it are original. 1. Where I have consulted the published work of others this is always clearly attributed. 2. Where I have quoted from the work of others the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations this dissertation is entirely my own work. 3. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. 4. If my research follows on from previous work or is part of a larger collaborative research project I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. 5. I am aware and accept the penalties associated with plagiarism. Date: Signature v vi Abstract Feminism in Bellydance and its portrayal in the media Meghana B.S MS in Communication, Christ University, Bengaluru Bellydance is an art form that has gained tremendous popularity in the world today. -

Headline News

Satuday, Thoroughbred Daily News January 26, 2002 TDN For information, call (732) 747-8060. HEADLINE NEWS IS THE SANTA MONICA A STRETCH? T.M. OPERA O TO EAST STUD Kalookan Queen (Lost Code) has won seven of her Japanese champion T.M. Opera O (Jpn) (Opera House 17 career starts, all sprints, but she is 0-for-four at {GB}--Once Wed, by Blushing Groom {Fr}), who made seven furlongs. The six-year-old mare will try to break his final career start when fifth in the Dec. 23 Arima that streak with a victory in today’s GI Santa Monica H. Kinen at Nakayama, will begin stallion duties at East at Santa Anita. The dark bay has run well at seven Stud on the island of Hokkaido this year. He goes to panels in the past, finishing third in the GI La Brea S. at the breeding shed as the all-time leading money winner the end of 1999 and second, beaten only a length by in Thoroughbred racing history with earnings of Honest Lady, in the 2000 edition of the Santa Monica. $16,200,337, more than $6.2 million ahead of Ameri- She has also taken three of her last four outings, win- can superstar Cigar. T.M. Opera O was named Japan’s ning the July 23 Fantastic Girl S. and the Aug. 19 GIII champion three-year-old colt after taking the Japanese Rancho Bernardo H., both going 6 1/2 furlongs at Del 2000 Guineas, then had a perfect season at four, win- Mar, before running third after a rough start in the GII ning all eight starts. -

Book-14 Web-Lmsx.Pdf

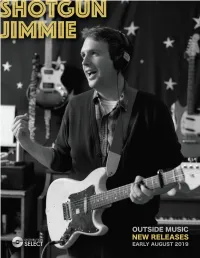

SHOTGUN JIMMIE – TRANSISTOR SISTER 2 LABEL: YOU’VE CHANGED RECORDS CATALOG: YC-039 FORMAT: LP/CD RELEASE DATE: AUGUST 2, 2019 Are you ready for the new sincerity?! Shotgun Jimmie’s new album Transistor Sister 2 is full of genuine pop gems that champion truth and love. Jimmie is joined by long- time collaborators Ryan Peters (Ladyhawk) and Jason Baird (DoMakeSayThink) for this sequel to the Polaris Prize nominated album Transistor Sister from 2011. José Contreras (By Divine Right) produced and recorded the record in Toronto, Ontario at The Chat Chateaux and joins the band on keys. In characteristic Shotgun Jimmie fashion, the songs on Transistor Sister 2 focus largely on family and friends with a heavy dose of nostalgia. Jimmie’s hyperbolic takes on the everyday reconstruct familiar scenarios, from traffic on the 401 (the beloved and scorned mega- highway through Toronto known to all touring musicians Blues Riffs as the place where punctual arrival at soundcheck goes Tumbleweed to die) to cooking dinner. Hot Pots Ablutions The album’s lead single Cool All the Time is a plea for Fountain people to abandon ego and strive for authenticity, Suddenly Submarine featuring contributions by Chad VanGaalen, Steven Piano (with band) Lambke and Cole Woods. The New Sincerity serves as The New Sincerity the album’s manifesto; it renounces cynicism and Cool All The Time promotes positivity. Sappy Slogans Highway 401 Jack Pine Sorry We’re Closed Shotgun Jimmie: IG: @shotgunjimmie FB: @shotgunjimmie Twitter: @jimmieshotgun You’ve Changed Records: www.youvechangedrecords.com CD – CD-YC-039 LP with download – LP-YC-039 Twitter: @youvechangedrec IG: @youvechangedrecords FB: @youvechangedrecords Also available from You’ve Changed Records: Partner – Saturday The 14th (YC-038) 12”EP/CD You’ve Changed Records Steven Lambke – Dark Blue (YC-037) LP 123 Pauline Ave. -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe.