Conclusion—Football, Postmodernism, and Us 125

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of an Offensive Signal System Using Words Rather Than Numbers and Including Automatics

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1958 A study of an offensive signal system using words rather than numbers and including automatics Don Carlo Campora University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Health and Physical Education Commons Recommended Citation Campora, Don Carlo. (1958). A study of an offensive signal system using words rather than numbers and including automatics. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/ 1369 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r, i I l I I\ IIi A ..STUDY OF AN OFFENSIVE SIGNAL SYSTEM USING WORDS RATHER THAN NUMBERS AND INCLUDING AUTOMATICS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Physical Education College of the Pacific In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree .Master of Arts by Don Carlo Campora .. ,.. ' TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION • . .. • . .. • • 1 Introductory statement • • 0 • • • • • • • 1 The Problem • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. 4 Statement of the problem • • • • • • 4 Importance of the topic • • • 4 Related Studies • • • • • • • • • • • 9 • • 6 Definitions of Terms Used • • • • • • • • 6 Automatics • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Numbering systems • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Defense • • • • • • • • • • o- • • • 6 Offense • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 6 Starting count • • • • • • • • 0 6 "On" side • • • • • • • • 0 • 6 "Off" side • " . • • • • • • • • 7 Scouting report • • • • • • • • 7 Variations • • .. • 0 • • • • • • • • • 7 Organization of the Study • • • • • • • • • • • 7 Review of the literature • • • • . -

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

Download Brochure (PDF)

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2019 PRESENTED BY BENEFITTING THE THE LEGACY OF JOHN FRANKLIN BROYLES Frank Broyles always said he lived a “charmed life,” and it was true. He leaves behind a multitude of legacies certain never to be replicated. Whether it was his unparalleled career in college athletics as an athlete, coach, athletic administrator and broadcaster, or his Broyles, SEC 1944 Player of the Year, handled all the passing (left) and punting (right) from his tailback spot playing for Georgia Tech under legendary Coach tireless work in the fourth quarter of his life Bobby Dodd as an Alzheimer’s advocate, his passion was always the catalyst for changing the world around him for the better, delivered with a smooth Southern drawl. He felt he was blessed to work for more than 55 years in the only job he ever wanted, first as head football coach and then as athletic director at the University of Arkansas. An optimist and a visionary who looked at life with an attitude of gratitude, Broyles lived life Broyles provided color Frank and Barbara Broyles beam with their commentary for ABC’s coverage of to the fullest for 92 years. four sons and newborn twin daughters college football in the 1970’s Coach Broyles’ legacy lives on through the countless lives he impacted on and off the field, through the Broyles Foundation and their efforts to support Alzheimer’s caregivers at no cost, and through the Broyles Award nominees, finalists, and winners that continue Broyles and Darrell Royal meet at to impact the world of college athletics and midfield after the 1969 #1 Texas vs. -

Nfl Network Celebrates Black History Month with Expansive Programming Lineup

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Andrew Howard – 310.845.4579 NFL Media – 2/2/21 [email protected] NFL NETWORK CELEBRATES BLACK HISTORY MONTH WITH EXPANSIVE PROGRAMMING LINEUP ‘NFL Total Access: Say Their Stories’ Kicks Off Week of Primetime Specials Monday, February 15 at 8:00 PM ET All-Day Marathon of Programming on Sunday, February 21 – Premiere of ‘NFL 360: 2021 Black History Month Special’ at 8:00 PM ET & ‘NFL Roundtables: Field Generals’ at 9:00 PM ET Powerful New Features ‘Game Changer’ & ‘Michael Vick: The Bridge Between’ NFL Network celebrates Black History Month with a wide array of programming throughout the month of February dedicated to honoring the iconic people, stories and events that have shaped the NFL, beginning on Super Bowl Sunday February 7. Every weeknight in primetime during the week of February 15 starting at 8:00 PM ET NFL Network airs a three-hour block of original programming in celebration of Black History Month, beginning with a special edition of NFL Total Access on Monday, February 15 hosted by MJ Acosta-Ruiz, Steve Wyche and Patrick Claybon showcasing some of the most powerful “Say Their Stories” features from over the course of the past season. Additional programming highlights each night on NFL Network February 15-19 include The Super Bowl That Wasn’t, NFL 360 – Fritz Pollard: A Forgotten Man, Breaking Ground: A Story of HBCU Football and the NFL, relevant editions of A Football Life, and more. The week of programming culminates with an all-day marathon of programming on Sunday, February 21 beginning at 6:00 AM ET, which includes the premieres of NFL 360: 2021 Black History Month Special at 8:00 PM ET and NFL Roundtables: Field Generals at 9:00 PM ET. -

Professional Football Researchers Association

Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com Marty Schottenheimer This article was written by Budd Bailey Marty Schottenheimer was a winner. He’s the only coach with at least 200 NFL wins in the regular season who isn’t in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Marty made bad teams good, and good teams better over the course of a coaching career that lasted more than 30 years. He has a better winning percentage than Chuck Noll, Tom Landry and Marv Levy – all Hall of Famers. “He not only won everywhere he went, but he won immediately everywhere he went,” wrote Ernie Accorsi in the forward to Schottenheimer’s autobiography. “That is rare, believe me.” The blemish in his resume is that he didn’t win the next-to-last game of the NFL season, let alone the last game. The easy comparison is to Chuck Knox, another fine coach from Western Pennsylvania who won a lot of games but never took that last step either. In other words, Schottenheimer never made it to a Super Bowl as a head coach. Even so, he ranks with the best in the coaching business in his time. Martin Edward Schottenheimer was born on September 23, 1943, in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. That’s about 22 miles from Pittsburgh to the southwest. As you might have guessed, that part of the world is rich in two things: minerals and football players. Much 1 Professional Football Researchers Association www.profootballresearchers.com of the area was employed directly or indirectly by the coal and steel industries over the years. -

Foot Ball Seems to Be Usurping the Place of Base Ball.” Football in Kansas, 1856–1891

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Monographs 2020 “Foot Ball Seems To Be Usurping the Place of Base Ball.” Football in Kansas, 1856–1891 Mark E. Eberle Fort Hays State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/all_monographs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Eberle, Mark E., "“Foot Ball Seems To Be Usurping the Place of Base Ball.” Football in Kansas, 1856–1891" (2020). Monographs. 17. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/all_monographs/17 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Monographs by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. “Foot Ball Seems To Be Usurping the Place of Base Ball.” Football in Kansas, 1856–1891 Mark E. Eberle “Foot Ball Seems To Be Usurping the Place of Base Ball.” Football in Kansas, 1856–1891 © 2020 by Mark E. Eberle Cover image used with permission of the University Archives, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas, Lawrence. Recommended citation: Eberle, Mark E. 2020. “Foot Ball Seems To Be Usurping the Place of Base Ball.” Football in Kansas, 1856–1891. Fort Hays State University, Hays, Kansas. 23 pages. “Foot Ball Seems To Be Usurping the Place of Base Ball.” Football in Kansas, 1856–1891 Mark E. Eberle Following the US Civil War, the sport of baseball spread across the young state of Kansas nearly as fast as new towns were established. It quickly supplanted cricket,1 but what of the other potential competitor in team sports—football? Early ball-and-stick games evolved into the game we now recognize as baseball during the mid-1800s.2 This same period also saw the evolution of the sport known as football in Great Britain. -

1956 Topps Football Checklist

1956 Topps Football Checklist 1 John Carson SP 2 Gordon Soltau 3 Frank Varrichione 4 Eddie Bell 5 Alex Webster RC 6 Norm Van Brocklin 7 Packers Team 8 Lou Creekmur 9 Lou Groza 10 Tom Bienemann SP 11 George Blanda 12 Alan Ameche 13 Vic Janowicz SP 14 Dick Moegle 15 Fran Rogel 16 Harold Giancanelli 17 Emlen Tunnell 18 Tank Younger 19 Bill Howton 20 Jack Christiansen 21 Pete Brewster 22 Cardinals Team SP 23 Ed Brown 24 Joe Campanella 25 Leon Heath SP 26 49ers Team 27 Dick Flanagan 28 Chuck Bednarik 29 Kyle Rote 30 Les Richter 31 Howard Ferguson 32 Dorne Dibble 33 Ken Konz 34 Dave Mann SP 35 Rick Casares 36 Art Donovan 37 Chuck Drazenovich SP 38 Joe Arenas 39 Lynn Chandnois 40 Eagles Team 41 Roosevelt Brown RC 42 Tom Fears 43 Gary Knafelc Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Joe Schmidt RC 45 Browns Team 46 Len Teeuws RC, SP 47 Bill George RC 48 Colts Team 49 Eddie LeBaron SP 50 Hugh McElhenny 51 Ted Marchibroda 52 Adrian Burk 53 Frank Gifford 54 Charles Toogood 55 Tobin Rote 56 Bill Stits 57 Don Colo 58 Ollie Matson SP 59 Harlon Hill 60 Lenny Moore RC 61 Redskins Team SP 62 Billy Wilson 63 Steelers Team 64 Bob Pellegrini 65 Ken MacAfee 66 Will Sherman 67 Roger Zatkoff 68 Dave Middleton 69 Ray Renfro 70 Don Stonesifer SP 71 Stan Jones RC 72 Jim Mutscheller 73 Volney Peters SP 74 Leo Nomellini 75 Ray Mathews 76 Dick Bielski 77 Charley Conerly 78 Elroy Hirsch 79 Bill Forester RC 80 Jim Doran 81 Fred Morrison 82 Jack Simmons SP 83 Bill McColl 84 Bert Rechichar 85 Joe Scudero SP 86 Y.A. -

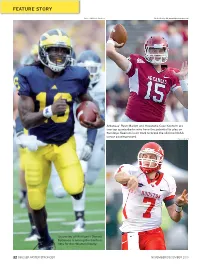

Feature Story

FEATURE STORY 3KRWR803KRWR6HUYLFHV 3KRWR:HVOH\+LWWZZZKLWWSKRWRJUDSK\FRP Arkansas’ Ryan Mallett and Houston’s Case Keenum are two top quarterbacks who have the potential to play on Sundays. Keenum is on track to break the all-time NCAA career passing record. 3KRWR8+6,' University of Michigan’s Denard Robinson is among the frontrun- ners for the Heisman Trophy. 32 | BIGGER FASTER STRONGER NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2010 2010 College Football Progress Report A look at another unpredictable season ne of the fascinating aspects of of Navy versus Air Force, the battle to meet the president of the United college football is that anything between these two service academies is States. What other college rivalry can Ocan happen, and this year is unbelievable. I say this because in 2002 you name in which the average margin no exception. The Heisman race is still AFA won 48-7, and then the following of victory for the past seven games was up in the air; among the frontrunners happened: 4.7 points, with four of these games are Michigan’s Denard Robinson, last 2003: Navy 28-25 being decided by a single field goal! year’s winner Mark Ingram, Boise State’s 2004: Navy 24-21 This year, finally, the Fighting Kellen Moore, Ohio State’s Terrelle 2005: Navy 27-24 Falcons broke the Midshipmen’s win- Pryor and Arkansas’ Ryan Mallett. 2006: Navy 24-17 ning streak, coming through with a 14-6 There could be some all-time 2007: Navy 31-20 victory. records broken this year. Houston’s Case 2008: Navy 22-27 Unfortunately, the 2005 award was Keenum has a shot at the all-time career 2009: Navy 16-13 declared vacant due to violations sur- passing record, and Navy’s quarterback …with the winner earning the rounding Reggie Bush. -

Tcu-Smu Series

FROG HISTORY 2008 TCU FOOTBALL TCU FOOTBALL THROUGH THE AGES 4General TCU is ready to embark upon its 112th year of Horned Frog football. Through all the years, with the ex cep tion of 1900, Purple ballclubs have com pet ed on an or ga nized basis. Even during the war years, as well as through the Great Depres sion, each fall Horned Frog football squads have done bat tle on the gridiron each fall. 4BEGINNINGS The newfangled game of foot ball, created in the East, made a quiet and un offcial ap pear ance on the TCU campus (AddRan College as it was then known and lo cat ed in Waco, Tex as, or nearby Thorp Spring) in the fall of 1896. It was then that sev er al of the col lege’s more ro bust stu dents, along with the en thu si as tic sup port of a cou ple of young “profs,” Addison Clark, Jr., and A.C. Easley, band ed to gether to form a team. Three games were ac tu al ly played that season ... all af ter Thanks giv ing. The first con test was an 86 vic to ry over Toby’s Busi ness College of Waco and the other two games were with the Houston Heavy weights, a town team. By 1897 the new sport had progressed and AddRan enlisted its first coach, Joe J. Field, to direct the team. Field’s ballclub won three games that autumn, including a first victory over Texas A&M. The only loss was to the Univer si ty of Tex as, 1810. -

Welcome to Canadian Football 2017

PLAYER’S MANUAL WELCOME TO CANADIAN FOOTBALL 2017 Canuck Play is excited to present the only game that brings all the action of Canadian gridiron football to the PC desktop and console. To help our gamers get started, this manual is designed to guide you through game play and features on all platforms. CONTENTS – Click any item in the list to go directly to that page Welcome to Canadian Football 2017 .................................................................................................... 1 Game Play ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Novice Player ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Selecting a Team .................................................................................................................................. 3 Game Settings ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Rule Sets .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Entering The Game .............................................................................................................................. 5 Kicking ................................................................................................................................................. -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

The Evolution of Football Rules

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Student Research and Creative Works 2017 Symposium Symposium 2017 The Evolution of Football Rules Veronica Glanville Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.ewu.edu/srcw_2017 Part of the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Glanville, Veronica, "The Evolution of Football Rules" (2017). 2017 Symposium. 2. https://dc.ewu.edu/srcw_2017/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the EWU Student Research and Creative Works Symposium at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2017 Symposium by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Evolution of American Football Rules Veronica Glanville Eastern Washington University, Physical Education, Health and Recreation Department Mentor: Dr. Chadron Hazelbaker Abstract Football, as we know it, has changed significantly since its humble beginnings in 1892. In its early beginnings, football was an all-out brawl. The first football game was played in 1869. It was an intercollegiate contest between Rutgers and Princeton universities, but the game was played according to soccer rules modified from the London Football Association (Riess, 2011). During the next seven years, rugby gained popularity over soccer and modern football was launched from rugby (Riess, 2011). In 1876, the Intercollegiate Football Association (IFA) was formed by Columbia, Harvard, Princeton, and Yale universities (Riess, 2011). IFA was dedicated to playing football according to rugby rules (Riess, 2011). Walter Camp, now known as the father of American football, helped establish many of the first rules and regulations of football (Nelson, 1995).