Analysis of the Reaction of Residents of Baton Rouge to a Series of Television Editorials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communications Status Report for Areas Impacted by Hurricane Ida September 8, 2021

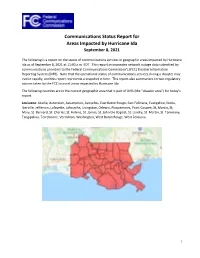

Communications Status Report for Areas Impacted by Hurricane Ida September 8, 2021 The following is a report on the status of communications services in geographic areas impacted by Hurricane Ida as of September 8, 2021 at 11:00 a.m. EDT. This report incorporates network outage data submitted by communications providers to the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Disaster Information Reporting System (DIRS). Note that the operational status of communications services during a disaster may evolve rapidly, and this report represents a snapshot in time. This report also summarizes certain regulatory actions taken by the FCC to assist areas impacted by Hurricane Ida. The following counties are in the current geographic area that is part of DIRS (the “disaster area”) for today’s report. Louisiana: Acadia, Ascension, Assumption, Avoyelles, East Baton Rouge, East Feliciana, Evangeline, Iberia, Iberville, Jefferson, Lafayette, Lafourche, Livingston, Orleans, Plaquemines, Point Coupee, St, Martin, St, Mary, St. Bernard, St. Charles, St. Helena, St. James, St. John the Baptist, St. Landry, St. Martin, St. Tammany, Tangipahoa, Terrebonne, Vermillion, Washington, West Baton Rouge, West Feliciana. 1 911 Services The Public Safety and Homeland Security Bureau (PSHSB) learns the status of each Public Safety Answering Point (PSAP) through the filings of 911 Service Providers in DIRS, reporting to the FCC’s Public Safety Support Center, coordination with state 911 Administrators and, if necessary, direct contact with individual PSAPs. Louisiana: No PSAPs are reported as being affected. The following chart shows the trend in the effects on PSAPs since the storm’s landfall: 2 Wireless Services The following section describes the status of wireless communications services and restoration in the disaster area. -

Hurricane-Guide-2021.Pdf

2021 HURRICANE PREPAREDNESS GUIDE Useful Apps In the event of an emergency Get A #WeGot You Game Plan Like and Follow these Social Media Pages American to Stay Informed on the Latest Updates Red Cross • Local Grocers • FEMA • National Weather Service • Local Red Cross FEMA (and for your specific area) • Local News and Radio Stations Alert FM Definitions/Terminology • Tropical Depression - An organized system of clouds and/or thunderstorms with a closed wind circulation and wind speeds of 39 mph or less. • Tropical Storm - An organized system of strong thunderstorms with a defined counterclockwise circulation and sustained wind speeds of 39-73mph. • Hurricane - An intense tropical weather system with pronounced rotary circulation and sustained wind speeds of 74 mph or more. A hurricane includes wind, heavy rains and a storm surge. • Watch - Conditions are POSSIBLE in the next 48 hours. • Warning - Conditions are EXPECTED in the next 36 hours. • Storm Surge - A rising of the sea along the shore that builds up as a storm moves over water. The result of atmospheric pressure changes and wind associated with a storm Saffir/Simpson Scale CATEGORY SUSTAINED WIND (mph) TYPE OF DAMAGE 1 74 to 95 Minimal 2 96 to 110 Moderate 3 111 to 130 Extensive 4 131 to 155 Extreme 5 Greater than 155 Catastrophic CATEGORY 1CATEGORY 2CATEGORY 3CATEGORY 4CATEGORY 5 74 - 95 mph96 - 110 mph 111 - 130 mph 131 - 155 mph155 + mph 2021 HURRICANE PREPAREDNESS GUIDE Shelters EVACUATION AREA INFORMATION POINT LOCATION Tallulah, LA TA Truck Stop — Exit 171 – I-20 at U.S. 65 Bunkie, LA Sammy’s Truck Stop — Exit 53 – I-49/3601 LA 115 W Alexandria, LA Y-Not — 7525 U.S. -

LOUISIANA NETWORK DMA Full State Plus Affiliate List

LOUISIANA NETWORK DMA Full State Plus Affiliate List MARKET STATION PARISH SIZE FREQ POWER FORMAT Alexandria DMA Alexandria KEDG-FM Rapides A 106.9 MHZ 6,000 Adult AC Alexandria KZMZ-FM Rapides C 96.9 MHZ 98,000 Rock Alexandria/Tioga KBKK-FM Rapides A 105.5 MHZ 6,000 Classic Country Alexandria/Tioga KLAA-FM Rapides A 103.5 MHZ 6,000 Country Bunkie KEZP-FM Avoyelles C 104.3 MHZ 19,200 Classic Rock Jena KJNA-FM LaSalle D 102.7 MHZ 6,000 Country Leesville KJAE-FM Vernon C 93.5 MHZ 7,500 Country Mansura KZLG-FM Avoyelles C 95.9 MHZ 6,000 AC Marksville KAPB-FM Avoyelles C 97.7 MHZ 6,000 Country Moreauville/Marksville KLIL-FM Avoyelles C 92.1 MHZ 6,000 Oldies Baton Rouge DMA Baton Rouge **** WXOK East Baton Rouge B 1460 KHZ 5,000 Gospel Baton Rouge WPFC East Baton Rouge D 1550 KHZ 5,000 Religious Hammond **** WCDV-FM Tangipahoa C 103.3 MHZ 100,000 AC Morgan City KQKI-FM St. Mary C 95.3 MHZ 16,500 Country New Roads KCLF Pointe Coupee C 1500 KHZ 1,000 Urban White Castle KKAY Iberville D 1590 KHZ 1,000 Variety Lafayette DMA Abbeville KROF Vermilion D 960 KHZ 1,000 Variety Crowley KSIG Acadia C 1450 KHZ 1,000 Easy Listening Erath ****** KRKA-FM Vermilion C 107.9 MHZ 97,000 Urban Eunice KEUN St. Landry C 1490 KHZ 1,000 News/Talk Lafayette KJCB Lafayette B 770 KHZ 1,000 Urban Lafayette ***** KPEL-FM Lafayette B 105.1 MHZ 25,000 News/Talk New Iberia KANE Iberia D 1240 KHZ 1,000 Oldies New Iberia **** KRDJ-FM Iberia C 93.7 MHZ 100,000 Classic Rock Opelousas KSLO St. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well DR. RALPH ABRAHAM Report Number: 80561 GOVERNOR PO Box 4247 Date Filed: 10/2/2019 Baton Rouge, LA 70821 STATE OF LOUISIANA Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule A-3 Schedule B 3. Date of Primary 10/12/2019 Schedule E-1 This report covers from 9/3/2019 through 9/22/2019 4. Type of Report: 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) X 10th day prior to primary 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more AMANDA MALOY banks, savings and loan associations, or money 742 NORTH 5TH STREET market mutual fund as the depository of all BATON ROUGE, LA 70802 RESOURCE BANK 9513 JEFFERSON HWY. BATON ROUGE, LA 70809 9. Name of Person Preparing Report AMANDA MALOY Daytime Telephone 225-767-7163 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. Name and address of principal campaign committee, expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, committee’s chairperson, and subsidiary committees, if and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure any (use additional sheets if necessary). -

Exploring the Atom's Anti-World! White's Radio, Log 4 Am -Fm- Stations World -Wide Snort -Wave Listings

EXPLORING THE ATOM'S ANTI-WORLD! WHITE'S RADIO, LOG 4 AM -FM- STATIONS WORLD -WIDE SNORT -WAVE LISTINGS WASHINGTON TO MOSCOW WORLD WEATHER LINK! Command Receive Power Supply Transistor TRF Amplifier Stage TEST REPORTS: H. H. Scott LK -60 80 -watt Stereo Amplifier Kit Lafayette HB -600 CB /Business Band $10 AEROBAND Solid -State Tranceiver CONVERTER 4 TUNE YOUR "RANSISTOR RADIO TO AIRCRAFT, CONTROL TLWERS! www.americanradiohistory.com PACE KEEP WITH SPACE AGE! SEE MANNED MOON SHOTS, SPACE FLIGHTS, CLOSE -UP! ANAZINC SCIENCE BUYS . for FUN, STUDY or PROFIT See the Stars, Moon. Planets Close Up! SOLVE PROBLEMS! TELL FORTUNES! PLAY GAMES! 3" ASTRONOMICAL REFLECTING TELESCOPE NEW WORKING MODEL DIGITAL COMPUTER i Photographers) Adapt your camera to this Scope for ex- ACTUAL MINIATURE VERSION cellent Telephoto shots and fascinating photos of moon! OF GIANT ELECTRONIC BRAINS Fascinating new see -through model compute 60 TO 180 POWER! Famous actually solves problems, teaches computer Mt. Palomar Typel An Unusual Buyl fundamentals. Adds, subtracts, multiplies. See the Rings of Saturn, the fascinating planet shifts, complements, carries, memorizes, counts. Mars, huge craters on the Moon, phases of Venus. compares, sequences. Attractively colored, rigid Equat rial Mount with lock both axes. Alum- plastic parts easily assembled. 12" x 31/2 x inized overcoated 43/4 ". Incl. step -by -step assembly 3" diameter high -speed 32 -page instruction book diagrams. ma o raro Telescope equipped with a 60X (binary covering operation, computer language eyepiece and a mounted Barlow Lens. Optical system), programming, problems and 15 experiments. Finder Telescope included. Hardwood, portable Stock No. 70,683 -HP $5.98 Postpaid tripod. -

FCC), October 14-31, 2019

Description of document: All Broadcasting and Mass Media Informal Complaints received by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), October 14-31, 2019 Requested date: 01-November-2019 Release date: 26-November-2019-2019 Posted date: 27-July-2020 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street, S.W., Room 1-A836 Washington, D.C. 20554 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site, and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Federal Communications Commission Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau Washington, D.C. 20554 tfltJ:J November 26, 2019 FOIA Nos. -

2021 Iheartradio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 iHeartRadio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM hotabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400 -

Showdown Has Lots of Losers, No Winners Photos by Jolice Provost of Capital City News City Capital of Provost Jolice by Photos

Baton Rouge’s CAPITALCAPITAL CITYCITY Community Newspaper ObamacareObamacare&& SmallSmall BusinessBusiness LouisianaLouisiana BlueBlue® CrossCross PresidentPresident MikeMike ReitzReitz SpeaksSpeaks atat ChamberChamber EBREBR •• 1212 noonnoon Tuesday,Tuesday, Feb.Feb. 2626 NEWSNEWS® Thursday, February 21, 2013 • Vol. 22, No. 3 • 12 Pages • www.capitalcitynews.us • Phone 225-261-5055 80-Year-Old WJBO vs. Upstart Talk 107.3 Capitol RadioCan Local Talk, Wars Personalities of 107.3 Challenge WJBO Loyalty? Woody Jenkins Editor, Capital City News BATON ROUGE — More than any other medium, radio represents the heart- beat of Baton Rouge. It’s where we go for the latest weather, breaking news, sports, and music. Radio has changed, but our at- tachment to the automobile has kept radio ever present. Radio is the best me- dium — the safest medium — for the highway. It uses just enough brain capacity Rush Limbaugh, 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. M-F, on WJBO Brian Haldane and Matt Kennedy of Talk 107.3 to keep you entertained and informed but not so much that it is likely to cause an Storied History of WJBO Just a Toddler, 107.3 Roars accident. Every other me- dium seems to have its ups and downs but, for now Began in a NO Basement At Powerful Competition BATON ROUGE — There little known conservative BATON ROUGE at least, radio is holding — For a to steal listeners for Talk steady. In Baton Rouge, have been many signifi- talk show host named Rush world-beater like Matt 107.3 from the heritage the history of radio begins cant moments in the his- Limbaugh. Kennedy, taking on his for- news talk station, WJBO. -

Broadcast Applications 2/6/2012

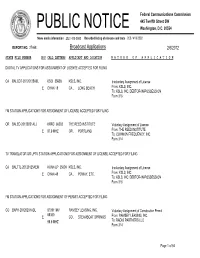

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27668 Broadcast Applications 2/6/2012 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N DIGITAL TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING CA BALCDT-20120125AEL KSCI 35608 KSLS, INC. Involuntary Assignment of License E CHAN-18 CA , LONG BEACH From: KSLS, INC. To: KSLS, INC. DEBTOR-IN-POSSESSION Form 316 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING OR BALED-20120201ALJ KRRC 66303 THE REED INSTITUTE Voluntary Assignment of License E 97.9 MHZ OR , PORTLAND From: THE REED INSTITUTE To: COMMON FREQUENCY, INC. Form 314 TV TRANSLATOR OR LPTV STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING CA BALTTL-20120125AEM KUAN-LP 35609 KSLS, INC. Involuntary Assignment of License E CHAN-48 CA , POWAY, ETC. From: KSLS, INC. To: KSLS, INC. DEBTOR-IN-POSSESSION Form 316 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF PERMIT ACCEPTED FOR FILING CO BAPH-20120201ADL 970911MV RAMSEY LEASING, INC. Voluntary Assignment of Construction Permit 88360 E CO , STEAMBOAT SPRINGS From: RAMSEY LEASING, INC. 98.9 MHZ To: RADIO PARTNERS LLC Form 314 Page 1 of 64 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27668 Broadcast Applications 2/6/2012 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF PERMIT ACCEPTED FOR FILING AR BAPH-20120201APS 970912MF 88358 JEM BROADCASTING CO., INC Voluntary Assignment of Construction Permit E 101.5 MHZ AR , GREENLAND From: JEM BROADCASTING CO., INC. -

LSU on the Air

Media Guidelines INTRO THIS IS LSU COACHES TIGERS OPPONENTS REVIEW HISTORY RECORDS LSU MEDIA MEDIA CREDENTIALS IMPORTANT MEDIA PHONE NUMBERS Media Credentials should be requested at least two days prior to LSU Sports Information (225) 578-8226 the game. Passes will be left at the entrance to Tiger Park on the LSU Sports Information Fax (225) 578-1861 day of the game. All requests should be made by writing or calling Melissa Reynaud office (225) 578-1869 Melissa Reynaud at the LSU Sports Information Office. Season Melissa Reynaud cell (225) 241-4365 passes can also be requested in this manner. Jim Hawthorne office (225) 578-1882 Tiger Park Press Box (225) 578-0155 VISITING RADIO A phone line is located in the press box for visiting radio broad- LSU IMAGE MEDIA DATABASE casts by Southeastern Conference opponents. Other teams wish- Members of the media can obtain photos on all LSU coaches and ing to do radio broadcasts must contact Jim Hawthorne of the LSU athletes as well as official LSU logos on the internet at Sports Network at (225) 578-1882. http://media.lsusports.net. The site features head shots and action shots of all of LSU's softball players. The site will be updated GAME INFORMATION weekly throughout softball season. To gain access to the database, Game information will be provided in the press box located above please contact Melissa Reynaud in the LSU Sports Information the bleachers directly behind home plate. NCAA boxscores and Department for a login and password. final game books will be distributed to members of the working media following each game. -

Krve, Wfmf, Wjbo, Wlro, Wynk-Fm Eeo Public File Report I. Vacancy List

Page: 1/7 KRVE, WFMF, WJBO, WLRO, WYNK-FM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2020 - January 31, 2021 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Outside Account Executive 1-5, 7-8, 10-32 7 Digital Sales Strategist 1, 3-6, 8-9, 12-14, 16-23, 25-32 9 Page: 2/7 KRVE, WFMF, WJBO, WLRO, WYNK-FM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2020 - January 31, 2021 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") Source Entitled No. of Interviewees RS to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Number Notification? Over (Yes/No) Reporting Period BR School of Computers 9255 Interline Avenue Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70809 1 Phone : 225-923-2525 N 0 Fax : 225-923-2979 Pam Smith Camelot Career College 2618 Wooddale Blvd Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70805 2 Phone : 225-928-3005 N 0 Fax : 225-927-3794 Ronnie Williams City of Baton Rouge – Career & Job Center 4523 Plank Road Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70805 3 Phone : 225-358-4579 N 0 Fax : 1-225-357-9675 Cynthia Douglas Delta College 7380 Exchange Place Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70806 4 Phone : 225-927-7780 N 0 Fax : 225-927-9096 Amy Renn Department of Labor Job Service 1991 Wooddale Blvd Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70806 5 Phone : 225-925-4311 N 0 Fax : 225-925-1845 Jennifer Johnson DirectEmployers.org 9002 N. Purdue Rd., Ste 100 Indianapolis, Indiana 46268 6 Phone : 317-874-9021 N 0 Url : http://www.directemployers.org/ Email : [email protected] Christy Merriman 7 Employee Referral N 1 Page: 3/7 KRVE, WFMF, WJBO, WLRO, WYNK-FM EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT February 1, 2020 - January 31, 2021 II.