Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cameron Graves – A.K.A

Cameron Graves – A.K.A. The Planetary Prince – Brings Thrash-Jazz to the Universe with Seven Album Features Special Guest Kamasi Washington Alongside Guitarist Colin Cook, Bassist Max Gerl, and Drummer Mike Mitchell Pianist, composer and vocalist Cameron Graves calls the music he’s architected for his new Artistry Music/Mack Avenue Music Group release thrash-jazz, though that only begins to tell the story. Yes, upon an initial listen, the juggernaut metal force and hardcore precision of Seven can knock you back. After all, Graves grew up in metal-rich Los Angeles, headbanging to Living Colour as a kid and, after immersing himself in jazz and classical studies for years, reigniting his love for hard rock through records by Pantera, Slipknot and his most profound metal influence, Swedish titans Meshuggah. But listen closer to Seven, Graves’ follow-up to 2017’s Planetary Prince (which Pitchfork called a “rousing debut”). “Los Angeles is a melting pot of everything,” Graves points out. His father, Carl Graves, was a great soul singer, and you can hear his imprint along with the likes of Marvin Gaye and Otis Redding, on “Eternal Paradise,” which marks the younger Graves’ vocal debut. Throughout the album, the generation of 1970s jazz-rock fusion pioneers is a source of inspiration. “Our mission is to continue that legacy of advanced music that was started by bands like Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report and Return to Forever,” Graves says. “That was instilled in us by the masters. Stanley Clarke, Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock—these guys sat with us and told us, ‘Look, man, you’ve got to carry this on.’” The “us” that Graves refers to would include the core quartet on Seven, as well as the West Coast Get Down, the now well-known expansive yet fraternal clique of high school friends who became some of the most influential jazz-rooted musicians to emerge in recent decades: saxophonist Kamasi Washington, who guests on two of Graves’ 11 new tracks; bassists Thundercat and Miles Mosley; drummers Ronald Bruner Jr. -

Gee Ray Records Newsletter Cover

HIP HOP GEE RAY RECORDS NEWSLETTER COVER TABLE OF CONTENT GEE RAY RECORDS NEWSLETTER EYESLICK PROMOTION HMTVN NETWORK * PROMOTIONAL OPPORTUNITIES EYESLICK INVITATION * INTERNET RADIO STATION MARCH NEWSLETTER * PLAYLIST PROMOTION GEE RAY RECORDS NEWSLETTER AH… REAL GOOD, FEEL GOOD MUSIC Gee Ray Records has been in the online music business for over 10 years. We have been fortunate to be associated with many talented people from the television, radio and music industries. The genres we broadcast are Dance, Deep House, Jazz, Electronica, Neo Soul, R&B, Hip Hop, Reggae, Music Videos and Talk Shows. Listen to Gee Ray Records on Spotify. Just click the link below and tune in. https://goo.gl/QrvZpQ Want to gain instant access to our Internet Radio Station? Click or tap the link below to tune in via your desktop or mobile device. http://geerayrecords.com Do you like music videos? Of course you do. You can now tap into a wide variety of music videos from both popular and independent recording artists plus an array of notable disk jockeys. Visit: http://hotmusictvnetwork.com Are you a fan of House, R&B, Hip Hop, Dance and Jazz music? Do you find yourself constantly searching for music online? You might want to check out this website which could have what you are looking for. Click link to learn more. http://hotmusicshop.com Pg. 1 NEW VIDEO WATCH R&B Party Mix – Mixed By Dj Xclusive G2b – Jaheim, Chris Brown, Mary J Blige, Ashanti: Visit our music channel. If you feel happy with the music please like, share and subscribe. -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

SEED Ensemble & Guests: Celebrating the Music of Pharoah Sanders Live

SEED Ensemble & guests: celebrating the music of Pharoah Sanders Live from the Barbican Start time: 8pm Approximate running time: 60 minutes, no interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change. This performance is subject to government guidelines. Arwa Haider examines SEED Ensemble’s influences and musical style. When London band SEED Ensemble emerged around four years ago, they were hailed as proof of thrilling new revolutions in the UK music scene, and among its jazz musicians – crucially repping its creative fluidity, and linking generations of inspiration across music and other art forms with 21st century youth culture. The talented instrumentalists in SEED Ensemble simultaneously play their parts in a range of other contemporary acts, and are led by composer, arranger and alto saxophonist Cassie Kinoshi, also a key figure in the outfits Kokoroko and Nerija. The combination of these elements and visions yields a sound that is expansive, musically adventurous, and excitingly immediate. They earned a Mercury Prize nomination for their brilliant 2019 debut album Driftglass, released on the seminal Jazz re:freshed label, and taking its name from a novel by the Black American sci-fi novelist and queer theorist Samuel R Delaney. Its tracks are enriched with personal experience – in particular, pan-African and Caribbean roots – political references and pop cultural hooks, creating an exploration of the undeniable issues in modern British society, as well as a spirit-soaring celebration of Black British experience. SEED Ensemble offer a lucid heads-up, that jazz is essentially ‘a community genre for everyone’ (as Kinoshi remarked in a Jazzwise interview), and that this latest explosion is deep-rooted, including the disparity of Black voices, and the presence of strong female leaders and collaborators. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

JACK RUTBERG FINE ARTS Reflections Through Time

JACK RUTBERG FINE ARTS 357 N. La Brea Avenue ∙ Los Angeles, CA 90036 ∙ Tel (323) 938-5222 ∙ www.jackrutbergfinearts.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jack Rutberg (323) 938-5222 [email protected] June 13 – September 30, 2015 Reflections Through Time Los Angeles, CA – Celebrated L.A. contemporary artist Ruth Weisberg is the subject of a new exhibition entitled “Ruth Weisberg: Reflections Through Time,” opening with a reception for the artist from 6:00 to 9:00 p.m. on Saturday, June 13, at Jack Rutberg Fine Arts, located at 357 North La Brea Avenue in Los Angeles. The exhibition extends through September 30. “Ruth Weisberg: Reflections Through Time” expands upon the recent Weisberg exhibition at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, presented on the occasion of receiving the prestigious 2015 Printmaker Emeritus Award from the Southern Graphics Council, the largest international body of “Waterbourne,” 1973, Lithograph, 30 1/4 x 42 1/4 Inches printmakers in North America. (The SGC’s previous awardee, in 2014, was Wayne Thiebaud.) Included in “Reflections Through Time” are selected works, such as Weisberg’s iconic “Waterbourne” (1973). Here the artist joins both symbolic and literal reflections of light, and in this case, a personal passage of impending motherhood and the emergence of woman. Other works in the exhibition, including her most recent work “Harbor” (2015), engage reflections on personal history and of the convergence of art history and cultural experience. “Reflections Through Time” reveals Weisberg’s decades-long interest in re-imagining the works of past masters such as Velazquez, Watteau, Blake, Titian, Veronese, Cagnacci, Corot, and Giacometti. -

NEW RELEASE Cds 24/5/19

NEW RELEASE CDs 24/5/19 BLACK MOUNTAIN Destroyer [Jagjaguwar] £9.99 CATE LE BON Reward [Mexican Summer] £9.99 EARTH Full Upon Her Burning Lips £10.99 FLYING LOTUS Flamagra [Warp] £9.99 HAYDEN THORPE (ex-Wild Beasts) Diviner [Domino] £9.99 HONEYBLOOD In Plain Sight [Marathon] £9.99 MAVIS STAPLES We Get By [ANTI-] £10.99 PRIMAL SCREAM Maximum Rock 'N' Roll: The Singles [2CD] £12.99 SEBADOH Act Surprised £10.99 THE WATERBOYS Where The Action Is [Cooking Vinyl] £9.99 THE WATERBOYS Where The Action Is [Deluxe 2CD w/ Alternative Mixes on Cooking Vinyl] £12.99 AKA TRIO (Feat. Seckou Keita!) Joy £9.99 AMYL & THE SNIFFERS Amyl & The Sniffers [Rough Trade] £9.99 ANDREYA TRIANA Life In Colour £9.99 DADDY LONG LEGS Lowdown Ways [Yep Roc] £9.99 FIRE! ORCHESTRA Arrival £11.99 FLESHGOD APOCALYPSE Veleno [Ltd. CD + Blu-Ray on Nuclear Blast] £14.99 FU MANCHU Godzilla's / Eatin' Dust +4 £11.99 GIA MARGARET There's Always Glimmer £9.99 JOAN AS POLICE WOMAN Joanthology [3CD on PIAS] £11.99 JUSTIN TOWNES EARLE The Saint Of Lost Causes [New West] £9.99 LEE MOSES How Much Longer Must I Wait? Singles & Rarities 1965-1972 [Future Days] £14.99 MALCOLM MIDDLETON (ex-Arab Strap) Bananas [Triassic Tusk] £9.99 PETROL GIRLS Cut & Stitch [Hassle] £9.99 STRAY CATS 40 [Deluxe CD w/ Bonus Tracks + More on Mascot]£14.99 STRAY CATS 40 [Mascot] £11.99 THE DAMNED THINGS High Crimes [Nuclear Blast] FEAT MEMBERS OF ANTHRAX, FALL OUT BOY, ALKALINE TRIO & EVERY TIME I DIE! £10.99 THE GET UP KIDS Problems [Big Scary Monsters] £9.99 THE MYSTERY LIGHTS Too Much Tension! [Wick] £10.99 COMPILATIONS VARIOUS ARTISTS Lux And Ivys Good For Nothin' Tunes [2CD] £11.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS Max's Skansas City £9.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS Par Les Damné.E.S De La Terre (By The Wretched Of The Earth) £13.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS The Hip Walk - Jazz Undercurrents In 60s New York [BGP] £10.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS The World Needs Changing: Street Funk.. -

(Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Indie Soul Meets Jazzy Blues

Artscape Entertainment Resource Guide 2013 Band Name Genre Website Email Phone Number Allie & The Cats (Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Indie Soul meets Jazzy Blues http://www.alliemariemusic.com [email protected] 4109916973 Balti Mare Balkan Gypsy Brass http://www.facebook.com/baltimare [email protected] 4109633799 Basement Instinct (Sound Off Live 2013 Winner) Alternative Rock https://www.facebook.com/basementinstinctband [email protected] 4437038941 Bearstronaut pop http://bearstronaut.com [email protected] 8609124857 Big Sur Alternative Melodic Rock http://www.bigsurrock.com [email protected] 3015931778 Billy Wilkins Jazz/Rock https://soundcloud.com/billy-wilkins-1 [email protected] 4103696360 Blizz Hip Hop http://www.hulkshare.com/Blizz [email protected] 4439860731 Boozey R&B and Hip Hop http://Boozeyonline.com [email protected] Braunsy Brooks & Worship Kulture Christian http://www.bbworshipkulture.com [email protected] 8284554010 Brittanie Thomas Music Soul/R&B http://www.brittaniethomas.com [email protected] 4433608985 Brothers Kardell Experimental electronic pop metal hip-hop http://www.soundcloud.com/brotherskardell [email protected] 2022862623 Buddah Bass Hip-Hop/Pop http://Buddahbass.bandcamp.com [email protected] 3365779559 Bumpin Uglies Reggae/Ska http://www.bumpinugliesmusic.com [email protected] 4102793613 Children of a Vivid Eden Alternative rock http://www.facebook.com/c.o.v.e.rock [email protected] 4436324130 Chris Reynolds and -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

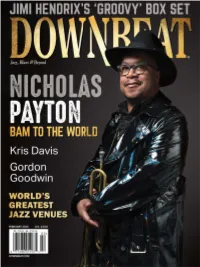

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

John Mcneil Bill Mchenry

John McNeil John McNeil is regarded as one of the most original and creative jazz artists in the world today. For nearly three decades John has toured with his own groups and has received widespread acclaim as both a player and composer. His highly personal trumpet style communicates across the full range of contemporary jazz, and his compositions combine harmonic freedom with melodic accessibility. John's restless experimentation has kept him on the cutting edge of new music. His background includes the Horace Silver Quintet, Gerry Mulligan, and the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra. John is equally at home in free and structured settings, and this versatility has put him on stage with artists from Slide Hampton to John Abercrombie. John McNeil was born in 1948 in northern California. Due to a lack of available musical instruction in his home town of Yreka, John largely taught himself to play trumpet and read music. By the time he graduated from high school in 1966, John had already begun playing professionally in the northern California region. John moved to New York in the mid-1970's and began a freelance career. His reputation as an innovative trumpet voice began to grow as he played with the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, and led his own groups at clubs such as Boomer's, the legendary Village jazz room. In the late 70's, John joined the Horace Silver Quintet. Around the same time, he began recording for the SteepleChase label under his own name and toured internationally. Although he has worked as a sideman with such luminaries as Gerry Mulligan, John has consistently led his own groups from about 1980 to the present. -

Robert Glasper's In

’s ION T T R ESSION ER CLASS S T RO Wynton Marsalis Wayne Wallace Kirk Garrison TRANSCRIP MAS P Brass School » Orbert Davis’ Mission David Hazeltine BLINDFOLD TES » » T GLASPE R JAZZ WAKE-UP CALL JAZZ WAKE-UP ROBE SLAP £3.50 £3.50 U.K. T.COM A Wes Montgomery Christian McBride Wadada Leo Smith Wadada Montgomery Wes Christian McBride DOWNBE APRIL 2012 DOWNBEAT ROBERT GLASPER // WES MONTGOMERY // WADADA LEO SmITH // OrbERT DAVIS // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2012 APRIL 2012 VOLume 79 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D.