Acushnet Company, and Roger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AP Monthly Exp Summary

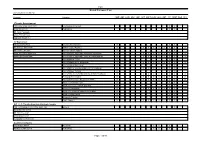

htr605 4/04/2017 City of Idaho Falls Expenditure Summary From 3/01/2017 To 3/31/2017 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Total Fund Expenditure ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ General Fund 2,175,031.68 Street Fund 53,381.49 Recreation Fund 48,274.25 Library Fund 80,550.71 MERF Fund 10,000.00 EL Public Purpose Fund 2,621.22 Golf Fund 139,553.31 Self-Insurance Fund 93,805.35 Municipal Capital Imp F 85,522.50 Parks Capital Imp Fund 21,477.76 Fire Capital Improvement 33,054.10 Airport Fund 162,468.60 Water & Sewer Fund 511,683.43 Sanitation Fund 7,820.62 Ambulance Fund 114,147.09 Electric Light Fund 3,122,752.03 Payroll Liability Fund 3,718,685.67 10,380,829.81 Htr603 4/04/17 City Of Idaho Falls Page 1 OPERATING EXPENSES PAID From 3/01/2017 To 3/31/2017 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Check Vendor Number Name Amount Description Fund ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 0000304 WNEBCO 2.60 RLR LIFE INS. MAR'2017 080 0000305 IDAHO NCPERS GROUP LIFE INS 1,392.00 PERSLIFE INS. MAR'2017 080 0000306 IDAHO FALLS FOP LODGE #6 2,640.00 POLICE UNION MAR'2017 080 0000307 LIFEMAP ASSURANCE COMPANY 3,201.12 SUPPLMNTAL LIFE MAR'17 080 0000308 IBEW LOCAL NO. 57 3,508.98 -

Callaway Golf Company (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-Q ☒ QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the quarterly period ended June 30, 2008 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period to Commission file number 001-10962 Callaway Golf Company (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 95-3797580 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 2180 Rutherford Road, Carlsbad, CA 92008 (760) 931-1771 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of principal executive offices) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, or a non-accelerated filer (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Large accelerated filer ☒ Accelerated filer ☐ Non-accelerated filer ☐ (Do not check if a smaller reporting company) Smaller reporting company ☐ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Yes ☐ No ☒ The number of shares outstanding of the Registrant’s Common Stock, $.01 par value, as of June 30, 2008 was 64,802,771. -

Vendor List for Campaign Contributions

VENDOR LIST FOR CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS Vendor # Vendor Name Address 1 Address 2 City State Contact Name Phone Email 371 3000 GRATIGNY ASSOCIATES LLC 100 FRONT STREET SUITE 350 CONSHOHOCKEN PA J GARCIA [email protected] 651 A & A DRAINAGE & VAC SERVICES INC 5040 KING ARTHUR AVENUE DAVIE FL 954 680 0294 [email protected] 1622 A & B PIPE & SUPPLY INC 6500 N.W. 37 AVENUE MIAMI FL 305-691-5000 [email protected] 49151 A & J ROOFING CORP 4337 E 11 AVENUE HIALEAH FL MIGUEL GUERRERO 305.599.2782 [email protected] 881 A JOY WALLACE CATERING PRODUCTION INC 8501 SW 128 TERRACE MIAMI FL PRISCILLA 305-252-0020 [email protected] 45432 A QUICK BOARD-UP SERVICE, INC. 10501 NW 50 STREET STE 101 SUNRISE FL DAN KALELY 954-764-4282 [email protected] 7928 AAA AUTOMATED DOOR REPAIR INC 21211 NE 25 CT MIAMI FL 305-933-2627 [email protected] 608 AARDVARK 1935 PUDDINGSTONE DRIVE LA VERNE CA TURNER 909 451 6100 [email protected] 48891 AARON CONSTRUCTION GROUP, INC. 10820 NW 138 STREET BAY C-1 HIALEAH GARDENS FL LINA 7863626120 [email protected] 35204 ABC TRANSFER INC. 307 E. AZTEC AVENUE CLEWISTON FL 863-983-1611 X 112 [email protected] 478 ACADEMY BUS LLC 3595 NW 110 STREET MIAMI FL V RUIZ 305-688-7700 [email protected] 980 ACAI ASSOCIATES, INC. 2937 W. CYPRESS CREEK ROAD SUITE 200 FORT LAUDERDALE FL 954-484-4000 [email protected] 49453 ACCESS LIFTS AND ELEVATORS INC 8362 PINES BLVD #380 PEMBROKE PINES FL MERCEDES BRUNO/ROCCO 561-373-6765 [email protected] -

UNIVERSITY of WYOMING TRADEMARK LICENSEES As of July 2, 2020

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING TRADEMARK LICENSEES as of July 2, 2020 Each of the companies listed below has entered into a trademark licensing agreement enabling them to produce and sell items bearing the University's intellectual property. These agreements include specific rights relative to trademark use, products, and sales and distribution. While some licensees are able to sell direct-to-consumer, a majority of these companies are licensed for wholesale sales activity only. Questions should be directed to [email protected] COMPANY / BRAND NAME: WEBSITE: * 47 Brand www.47brand.com 4imprint Inc. www.4imprint.com * Acushnet Company www.acushnetgolf.com adidas America www.adidas.com Adrenaline World Jerseys www.adrenalinepromotions.com Ajj Enterprises www.ajjcornhole.com * All Star Dogs www.allstardogs.com Alternative Apparel www.alternativeapparel.com American Collegiate www.american-collegiate.com Aminco International (USA) Inc. www.amincoUSA.com Angry Minnow Vintage www.angryminnowvintage.com Antigua Group, Inc. www.antigua.com Authentic Street Signs Inc. www.authenticstreetsigns.com Automotive Advertising Associates Inc. www.automotiveadvertisingassociates.com Baden Sports www.badensports.com Blakeway Worldwide Panoramas, Inc. www.panoramas.com * Boelter Brands LLC www.boelterbrands.com Boxercraft Inc. www.boxercraft.com/college Branded Custom Sportswear, Inc. (Nike) www.bcsapparel.com * Branded Logistics LLC (Fan Brander) www.branded-logistics.com Brass Reminders Co. www.brassreminders.com Broder Bros., Co. dba alphabroder www.alphabroder.com -

Affiliate Rewards Eligible Companies

Affiliate Rewards Eligible Companies Program ID's: 2012MY 2013MY 2014MY Designated Corporate Customer 28HCR 28HDR 28HER Fleet Company 28HCH 28HDH 28HEH Supplier Company 28HCJ 28HDJ 28HEJ Company Name Type 3 Point Machine SUPPLIER 3-D POLYMERS SUPPLIER 3-Dimensional Services SUPPLIER 3M Employee Transportation & Travel FLEET 84 Lumber Company DCC A & R Security Services, Inc. FLEET A B & W INC SUPPLIER A D E SUPPLIER A G Manufacturing SUPPLIER A G Simpson Automotive Inc SUPPLIER A I M CORPORATION SUPPLIER A M G INDUSTRIES INC SUPPLIER A T KEARNEYINC SUPPLIER A&D Technology Inc SUPPLIER A&E Television Networks DCC A. Raymond Tinnerman Automotive Inc SUPPLIER A. Schulman Inc SUPPLIER A.J. Rose Manufacturing SUPPLIER A.M Community Credit Union DCC A-1 SPECIALIZED SERVICES SUPPLIER AAA East Central DCC AAA National SUPPLIER AAA Ohio Auto Club DCC AARELL COMPANY SUPPLIER ABA OF AMERICA INC SUPPLIER ABB, Inc. FLEET Abbott Ball Co SUPPLIER ABBOTT BALL COMPANY THE SUPPLIER Abbott Labs FLEET Abbott, Nicholson, Quilter, Esshaki & Youngblood P DCC Abby Farm Supply, Inc DCC ABC GROUP-CANADA SUPPLIER ABC Widgit Company SUPPLIER Abednego Environmental Services SUPPLIER Abercrombie & Fitch FLEET Affiliate Rewards Eligible Companies Program ID's: 2012MY 2013MY 2014MY Designated Corporate Customer 28HCR 28HDR 28HER Fleet Company 28HCH 28HDH 28HEH Supplier Company 28HCJ 28HDJ 28HEJ ABERNATHY INDUSTRIAL SUPPLIER ABF Freight System Inc SUPPLIER ABM Industries, Inc. FLEET AboveNet FLEET ABP Induction SUPPLIER ABRASIVE DIAMOND TOOL COMPANY SUPPLIER Abraxis Bioscience Inc. FLEET ABSO-CLEAN INDUSTRIES INC SUPPLIER ACCENTURE SUPPLIER Access Fund SUPPLIER Acciona Energy North America Corporation FLEET Accor North America FLEET Accretive Solutions SUPPLIER Accu-Die & Mold Inc SUPPLIER Accumetric, LLC SUPPLIER ACCUM-MATIC SYSTEMS INC SUPPLIER ACCURATE MACHINE AND TOOL CORP SUPPLIER ACCURATE ROLL ENGINEERING CORP SUPPLIER Accurate Technologies Inc SUPPLIER Accuride Corporation SUPPLIER Ace Hardware Corporation FLEET ACE PRODUCTS INC SUPPLIER ACG Direct Inc. -

Conforming Golf Balls

Conforming Golf Balls Effective March 7, 2012 The List of Conforming Golf Balls will be updated effective the first Wednesday of each month. The updates will be available for download the Monday prior to each effective date. Please visit www.usga.org or www.randa.org for the latest listing. *Please note that the list is updated monthly (i.e., golf balls are added to and deleted from the list each month). The effective period of the Conforming Ball List is located on the top of each page. To ensure accurate rulings, access and print the Conforming Ball List by the first Wednesday of every month. HOW TO USE THIS LIST To find a ball: The balls are listed alphabetically by Pole marking (brand name or manufacturer name), then by Seam marking. Each ball type is listed as a separate entry. For each ball type the following information is given to the extent that it appears on the ball.* 1. Pole marking(s). For the purpose of identification, Pole markings are defined as the major markings, regardless of the actual location with respect to any manufacturing seams. 2. Color of cover. 3. Seam markings. For the purpose of identification, Seam markings, on the equator of the ball, are defined as the minor markings, regardless of the actual location with respect to any manufacturing seams. *NOTE: Playing numbers are not considered to be part of the markings. A single ball type may have playing numbers of different colors and still be listed as a single ball type. READING A LISTING Examples of listings are shown on the following page with explanatory notes. -

Retail Licensee List 2021-09-02 01:40:35 PM

CLC Retail Licensee List 2021-09-02 01:40:35 PM Licensee Category CAMP AMP SCWC GDC SMC DPT BDPT GLFS SGSS SMT ITC RRET TDLR OPC 2Thumbs Entertainment 107 Eaton Place Suite 320 Electronics & Content X X Cary, NC 27513 Publishing X X Mr. Sam Pasquale www.2thumbz.com [email protected] '47 Brand, LLC 15 Southwest Park Clothing Accessories X X X Westwood, MA 02090 Infant/Toddler Apparel X X X X X X X X X Ms. Kathleen Crane Men's Fashion Apparel X X X www.Twinsenterprise.com Men's/Unisex Adjustable Non-Wool Headwear X X X X X X X X X [email protected] Men's/Unisex Adjustable Wool Blend Headwear X X X X X X X X X Men's/Unisex Fleece X X X Men's/Unisex Other Headwear X X X X X X X X X Men's/Unisex Outerwear X X X Men's/Unisex Structured Stretch Fit Headwear X X X X X X X X X Men's/Unisex T-shirts X X X Men's/Unisex Unstructured Closed Back Headwear X X X X X X X X X Personal Accessories X X X X X X X X X Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) X X X X X X X X X Women's Fashion Tops X X X Women's Fleece Tops & Bottoms X X X Women's Headwear X X X X X X X X X Women's Loungewear/Activewear/Misc. X X X Women's Outerwear X X X Women's T-shirts X X X Youth Apparel X X X X X X X X X ACL LLC- The dba American Cornhole League 300 Technology Center Way, Suite 105 Games X Rock Hill, SC 29730 Mr. -

Acushnet Holdings Corp

2020 Annual Report Dear Valued Shareholder, We have always defined ourselves as an aspirational product, process and people company. It’s a simple truth about who we are and why we have earned the brand leadership positions we hold today. Our people were put to the ultimate test in 2020, but through their resilience and tenacity we posted the most successful second half of a fiscal year in company history and we have emerged stronger, healthier and energized for the opportunities ahead. A Reflection on 2020 The year was a tale of two distinct halves. The first half of the year forced the powering down of our businesses and facilities to prioritize the safety, health and well-being of our global associates. While the pandemic caused massive disruption to our workforce and operations, we began the hard work of reshaping the organization with new protocols so that those who were able to work remotely could do so and to enable our most important manufacturing facilities to resume operations in mid-May. This responsiveness and agility was a true testament to the dedication and passion of Acushnet’s associates. The second half of the year delivered its own unique challenges and opportunities. By June, as golf courses reopened, the game experienced a surge in rounds of play. The sport of golf became a respite for players around the world. Dedicated golfers found opportunities to play even more, recreational or lapsed golfers returned to the game as a healthy diversion, and families, including juniors, emerged in droves. On a company-wide basis, we quickly began to experience demand pressures, albeit most welcome ones, across all brands and product categories, which challenged our supply chain, our associates, and our ability to service our trade partners and golfers. -

INTA Corporate Member List

Corporate Members Name Address City Address State Address Country 100x Group Hong Kong Hong Kong 1661, Inc. Los Angeles California United States 1-800-Flowers.com, Inc. Carle Place New York United States 3M China Ltd. Shanghai Shanghai China 3M Company Saint Paul Minnesota United States 3M Deutschland GmbH Neuss Germany 3M India Ltd. Bangalore Karnataka India 3M Innovation Singapore Pte Ltd Singapore Singapore 3M KCI San Antonio Texas United States 3M United Kingdom PLC Bracknell Bracknell Forest United Kingdom 7-Eleven, Inc. Irving Texas United States AB Electrolux Stockholm Stockholms län Sweden Västra AB Volvo Göteborg Götalands län Sweden ABB ASEA Brown Boveri Ltd. Zürich Zürich Switzerland Abbott St.Paul Minnesota United States Abbott Laboratories Abbott Park Illinois United States Abbott Products Operations AG Allschwil Switzerland AbbVie Inc. Irvine California United States AbbVie Inc. North Chicago Illinois United States Abercrombie & Fitch Co. New Albany Ohio United States ABRO Industries, Inc. South Bend Indiana United States ACCO Brands Corporation Lake Zurich Illinois United States Activision Blizzard UK Ltd. Slough United Kingdom Activision Blizzard, Inc. Santa Monica California United States Activision Computer Technology (Shanghai) Co. Ltd. Shanghai Shanghai China Acument Intellectual Property Fenton Michigan United States Acushnet Company Fairhaven Massachusetts United States Aderans America Holdings, Inc. Beverly Hills California United States adidas Group Panama Panamá Panama Adidas Group, India Gurgaon Haryana India adidas International Marketing BV Amsterdam Netherlands adidas International, Inc. Portland Oregon United States ADOBE INC. San Jose California United States ADOBE INC. Tokyo Japan Aetna Inc. Hartford Connecticut United States Agilent Technologies, Inc. Santa Clara California United States Ahold Delhaize Licensing Sarl Genève Genève Switzerland AIDA Cruises Rostock Germany Aigle International S.A. -

3Q 2020 News Release

Acushnet Holdings Corp. Announces Third Quarter and Year-to-Date 2020 Financial Results Third Quarter and Year-to-Date 2020 Financial Results • Third quarter net sales of $482.9 million, up 15.7% year over year, up 15.1% in constant currency • Year-to-date net sales of $1,191.7 million, down 9.2% year over year, down 8.7% in constant currency • Third quarter net income attributable to Acushnet Holdings Corp. of $63.2 million, up 112.1% year over year • Year-to-date net income attributable to Acushnet Holdings Corp. of $74.4 million, down 27.9% year over year • Third quarter Adjusted EBITDA of $99.2 million, up 77.8% year over year • Year-to-date Adjusted EBITDA of $185.1 million, down 5.4% year over year FAIRHAVEN, MA – November 6, 2020 – Acushnet Holdings Corp. (NYSE: GOLF) ("Acushnet"), a global leader in the design, development, manufacture and distribution of performance-driven golf products, today reported financial results for the three and nine months ended September 30, 2020. “I am pleased to report that the positive momentum we saw in June and July for the game of golf and Acushnet products continued throughout the third quarter. Our team remained focused on meeting and exceeding the needs of our trade partners and golfers around the world, all while operating under new safety and social distancing protocols. Our strong third quarter results reflect this focus and commitment,” stated David Maher, Acushnet Company's President and Chief Executive Officer. Mr. Maher continued, “An important part of golf’s story in 2020 has been the incredible effort and leadership we have seen from the game’s caretakers – PGA Professionals and course operators who have done great work to position the sport as a safe, welcoming and fun recreational activity. -

UNIVERSITY of WYOMING TRADEMARK LICENSEES As of August 16, 2021

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING TRADEMARK LICENSEES as of August 16, 2021 Each of the companies listed below has entered into a trademark licensing agreement enabling them to produce and sell items bearing the University's intellectual property. These agreements include specific rights relative to trademark use, products, and sales and distribution. While some licensees are able to sell direct-to-consumer, a majority of these companies are licensed for wholesale sales activity only. Questions should be directed to [email protected] COMPANY / BRAND NAME: WEBSITE: 19 Nine www.19nine.com 33rd & Rawson (Dream & Fun) www.dreamandfun.com 47 Brand www.47brand.com 4imprint Inc. www.4imprint.com Acushnet Company www.acushnetgolf.com Adrenaline World Jerseys www.adrenalinepromotions.com Ajj Enterprises www.ajjcornhole.com All Star Dogs www.allstardogs.com Alternative Apparel www.alternativeapparel.com Angry Minnow Vintage www.angryminnowvintage.com Antigua Group, Inc. www.antigua.com Authentic Street Signs Inc. www.authenticstreetsigns.com Baden Sports www.badensports.com Barbarian Rugbywear www.barbarian.com Blakeway Worldwide Panoramas, Inc. www.panoramas.com Boelter Beverage Group www.beercup.com Boxercraft Inc. www.boxercraft.com/college Branded Custom Sportswear, Inc. (Nike) www.bcsapparel.com Branded Logistics LLC (Fan Brander) www.branded-logistics.com Brass Reminders Co. www.brassreminders.com Bruml Management dba Techstyles Sportswear www.techstyles.com BSI Products, Inc. www.bsiproducts.com BSN Sports www.bsnsports.com Camp David www.campdavid.com Church Hill Classics www.diplomaframe.com CI Sport Inc. www.cisport.com College Concepts LLC www.collegeconcepts.com Colosseum Athletics Corporation www.colosseumusa.com Commemorative Brands, Inc. dba Balfour www.balfour.com Commemorative Brands, Inc. -

Page 1 of 17 MINUTES of the MONDAY EVENING, MARCH 14

MINUTES OF THE MONDAY EVENING, MARCH 14, 2011 RESCHEDULED MEETING OF THE MONMOUTH COUNTY BOARD OF RECREATION COMMISSIONERS HELD IN THE “BEECH ROOM” OF THE THOMPSON PARK VISITOR CENTER, 1ST FLOOR, 805 NEWMAN SPRINGS ROAD, LINCROFT, NJ. The meeting was called to order by Chairman Edward J. Loud at 7:04 PM. The following were Present on roll call: Chairman Edward J. Loud Commissioners: Michael G. Harmon Violeta Peters N. Britt Raynor Kevin Mandeville Thomas E. Hennessy, Jr. Lillian G. Burry, Freeholder/MCPS Liaison The following were Absent on roll call: Commissioners: Vice Chairman Fred J. Rummel (Excused) David W. Horsnall (Excused) Melvin A. Hood (Excused) Also Present: James J. Truncer, Secretary-Director Andrea I. Bazer, County Counsel Bruce A. Gollnick, Assistant Director David M. Compton, Superintendent of Co. Parks Francine P. Lorelli, Purchasing Agent Nancy J. Borchert, Senior Personnel Assistant Andrew Spears, Superintendent of Recreation Spencer Wickham, Chief/Land Acq. & Design Karen Livingstone, Public Information/Volunteers Andrew R. Coeyman, Supv. Land Preservation Office Courtney Bison, Recreation Supervisor Chairman Loud read the following Statement of Adequate Public Notice: “Statement of Adequate Public Notice of Rescheduled Meeting in compliance with the ‘Open Public Meetings Act’, Laws of the State of NJ, Chapter 231, P.L. 1975. Notice of rescheduled meeting has been posted, and the Asbury Park Press and other newspapers circulated in Monmouth County, and the County Clerk have been noticed, including date, time and place, as approved on a motion by the Commission at their regular meeting of February 7, 2011, as required by law.” Chairman Loud led the Board in the salute to the flag and the Pledge of Allegiance and asked for the observance of a moment of silence.