Why Arthouse Movies Benefit from a Day-And-Date Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entertainment, Media & Sports Alert >> COVID-19 May Lead To

MAY 6, 2020 >> COVID-19 ALERT COVID-19 May Lead to Permanent Changes to Theatrical Film Distribution THE BOTTOM LINE With movie theaters across the country shut down, film distribution has >> Universal Picture’s move to radically changed during the COVID-19 crisis. bypass theatrical distribution Last week brought the first indication that some of these changes may outlast the acute with Trolls World Tour has the public health situation. potential to fundamentally shift the film distribution model. TROLLS WORLD TOUR STAYS HOME >> As Universal and other studios In the wake of the successful April 10 Video-On-Demand premiere of Trolls World Tour, look to compress or eliminate Universal Pictures announced on April 28 that, in the future, the studio would release films the exclusive theatrical simultaneously in theaters and on demand (VOD). Universal did not specify how many of distribution window, parties its films would get a simultaneous theatrical and VOD release, but the message was clear throughout the entertainment — the industry is about to change. industry will need to rethink negotiation strategies for a The elimination of the exclusive theatrical release window would represent a seismic variety of new and evolving shift in how films are distributed. In response to this threat to its business, AMC Theatres deal points. quickly announced that it would no longer exhibit any film released by Universal. Since the advent of the VHS cassette, film distributors and exhibitors have fought over the length of the exclusive theatrical window. Currently, the theatrical window for major studio films is about 75 days before digital sell-through begins and 90 days before DVD sales and digital rentals. -

Disruptive Innovators

3 Disruptive Innovators Introduction At this point in time, any examination of the classic Hollywood model of film distribution seems to be sorrowfully out of date. Ostensibly it might appear unquestionable that the distribution sector of the global film industry has been revolutionised in recent years. This surface image would seem to suggest that this transformation has ushered in an era of plenty, where a whole host of films and TV shows (not to mention books, computer games, web series and so on) are available within the blink of an eye. Furthermore, if we count the developing informal (and often illegal) channels of online distribution facilitated by the growth of the Internet, then the last 10–15 years has witnessed an explosion in the availability of films and TV programmes for audiences. At least, this is how it seems, and arguably there is some truth in this assessment of the current media distribution environment. However, I would argue that this veritable smörgåsbord of content is not universally available, nor is it presented in an unmediated form where audiences are free to pick and choose the content that interests them. As Finola Kerrigan has suggested, ‘on demand distribution is not the free for all panacea that some claim, as the structural impediments of the global film industry still prevail to a certain extent’ (2013). It is important to acknowledge that our film-viewing decisions are funnelled, curated and directed by these new mechanisms of online dis- tribution. As much as our film choice was once limited by the titles available in the high street video rental store or through our cable TV provider, online on-demand options are still shaped by the con- tracts and marketing arrangements discussed within Chapter 1 of this book. -

MADE in HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED by BEIJING the U.S

MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence 1 MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION 1 REPORT METHODOLOGY 5 PART I: HOW (AND WHY) BEIJING IS 6 ABLE TO INFLUENCE HOLLYWOOD PART II: THE WAY THIS INFLUENCE PLAYS OUT 20 PART III: ENTERING THE CHINESE MARKET 33 PART IV: LOOKING TOWARD SOLUTIONS 43 RECOMMENDATIONS 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 53 ENDNOTES 54 Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing: The U.S. Film Industry and Chinese Government Influence MADE IN HOLLYWOOD, CENSORED BY BEIJING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ade in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing system is inconsistent with international norms of Mdescribes the ways in which the Chinese artistic freedom. government and its ruling Chinese Communist There are countless stories to be told about China, Party successfully influence Hollywood films, and those that are non-controversial from Beijing’s warns how this type of influence has increasingly perspective are no less valid. But there are also become normalized in Hollywood, and explains stories to be told about the ongoing crimes against the implications of this influence on freedom of humanity in Xinjiang, the ongoing struggle of Tibetans expression and on the types of stories that global to maintain their language and culture in the face of audiences are exposed to on the big screen. both societal changes and government policy, the Hollywood is one of the world’s most significant prodemocracy movement in Hong Kong, and honest, storytelling centers, a cinematic powerhouse whose everyday stories about how government policies movies are watched by millions across the globe. -

The Future Ain't What It Used to Be

1 THE FUTURE AIN’T WHAT IT USED TO BE U.S. Entertainment: Where are We and Where Might We Go?* By Bruce Ramer INTRODUCTION to those with tangential links, such as Sony (Columbia) 2 “NOBODY KNOWS ANYTHING.” Nowhere is this and Matsushita (Universal). aphorism more true than in the business for which it Now we see acquirers coming with even stronger was invented, the entertainment business, where links to the media industries. Studio mergers and innovations in technology continue to create new acquisitions are led by companies that have massive platforms, with a ripple effect that leads to new forms scale and control significant distribution channels, of content and new consumer preferences and notably in the U.S. and China. Thus, Comcast acquired demands. That process has only accelerated as the NBC Universal, Dalian Wanda acquired AMC relevant technology changed from tubes and celluloid Theaters and AT&T proposed a merger deal with to chips and bits and from movie palaces and boxy TVs Time-Warner. Whether or not the AT&T deal closes to cellphones and the Internet. — and it appears it will — a new round of proposed The best way to think about the future is to start studio acquisitions is likely, with some of the potential with the past: to look back and see what has been domestic suitors including Google, Amazon (which is developing, and try to discern trends that inform the already heavily in the content business), Apple,(which direction of things to come — however, “history is not recently announced expanded entry into the content necessarily destiny.”3 Most of the borders and business)5 Facebook, Verizon and others. -

September 2005 September 2005 NATO of California/Nevada

NATO of California/Nevada September 2005 September 2005 NATO of California/Nevada Information for the California and Nevada Motion Picture Theatre Industry CALENDAR The Real “Story”: It’s the Movies! of EVENTS & No Seismic Shift in Consumer Preferences HOLIDAYS Compels Unwise Simultaneous Release National Association of Theatre Owners President John Fithian Responds to National NATO Disney Chairman Robert Iger on the Alleged Demand for Simultaneous Release Board Meeting in Chicago Washington, D.C. (August 18, 2005) – National Association of Sept. 14 – 15 Theatre Owners (NATO) President, John Fithian, issued the follow- ing statement in response to comments by Walt Disney Chairman • Robert Iger during a conference call with Wall Street analysts on Tuesday, August 9. Sexual Harassment “Walt Disney’s Robert Iger says American consumers demand Prevention it all and demand it now. To placate this instant-everywhere appe- Training tite, Iger suggests it may be necessary to release movies in theatres, Workshop on DVDs, and everywhere, at the same time. Sept. 20 - San Jose “Mr. Iger knows better than to tell consumers – or Wall Street Sept. 22 - Los Angeles analysts – that they can have it all, everywhere, at the same time. Oct. 18 - Sacramento He knows there would be no viable movie theatre industry in that new world – at least not a theatre industry devoted to the entertain- • ment products of Hollywood. And he should know that Hollywood studios would be merely one shriveled vendor among many in that John Fithian, NATO President Daylight Saving new world of movies-as-commodities-only. Time Ends “Iger considers the slowdown in theatre box office and DVD growth a ‘wake-up call’ for Oct. -

Black Widow Shows Theatrical Exclusivity Is

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BLACK WIDOW SHOWS THEATRICAL EXCLUSIVITY IS THE WAY FORWARD Strong opening and long-term performance in all windows undercut by simultaneous release; cannibalization of theatrical and later PVOD, and piracy reduce overall revenue (Los Angeles - 18 July 2021) Black Widow’s excellent reviews, positive word of mouth, and strong previews and opening day total ($13.2 million/$39.5 million) led to a surprising 41% second day drop, a weaker than expected opening weekend, and a stunning second weekend collapse in theatrical revenues. Why did such a well-made, well-received, highly anticipated movie underperform? Despite assertions that this pandemic-era improvised release strategy was a success for Disney and the simultaneous release model, it demonstrates that an exclusive theatrical release means more revenue for all stakeholders in every cycle of the movie’s life. Based on comparable Marvel titles, and other successful pandemic-era titles like F9 and A Quiet Place 2 opening day to weekend ratios, Black Widow should have opened to anywhere from $92-$100 million. Based on preview revenue, compared to the same titles, Black Widow could have opened to anywhere from $97 to $130 million. Early analysis pointed at the $60 million in Premiere Access revenue and compared it to the domestic theatrical of $80 million and declared it a success, especially because Disney keeps every dollar of home release. It does not. Approximately 15% of revenue goes to the various platforms through which consumers access Disney+. It ignores that Premiere Access revenue is not new-found money, but was pulled forward from a more traditional PVOD window, which is no longer an option. -

The Evolution of New Media

GREEN HASSON JANKS | FALL 2016 ENTERTAINMENT REPORT THE EVOLUTION OF NEW MEDIA MAKING MONEY IN A WORLD WHERE DIGITAL STREAMING RULES TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME LETTER FROM GREEN HASSON JANKS 03 ENTERTAINMENT AND MEDIA PRACTICE LEADER 04 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 06 SURVEY HIGHLIGHTS 08 INDUSTRY EXPERTS 09 GREEN HASSON JANKS EXPERTS 10 GLOBALIZATION 16 MONETIZATION LOOKING TO 26 THE FUTURE 31 ABOUT THE SURVEY RESPONDENTS 32 KEY TAKEAWAYS 36 ABOUT GREEN HASSON JANKS AUTHORS 38 ABOUT GREEN HASSON JANKS CONTRIBUTORS 41 ABOUT THE SUBJECT MATTER EXPERTS 2 WELCOME The entertainment and media industry is moving quickly, driven by technology and industry disrupters. We cannot predict the future, but we have assembled a stellar group of industry experts to share their knowledge and expectations on the topic of monetization and globalization. I am proud of my team’s authorship of our 4th annual whitepaper, and found it to be an important read on where we are heading as an industry and as a profession. I hope you will also find this whitepaper informative and thought provoking – it is part of our continuing efforts to provide value to the entertainment community. If you have ideas, feedback or your own story to share, please do not hesitate to contact me. Ilan Haimoff Partner and Entertainment and Media Practice Leader, Green Hasson Janks [email protected] 310.873.1651 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Streaming services have emerged as significant disrupters in the entertainment industry. With this in mind, the Green Hasson Janks 2016 Entertainment and Media Survey and industry expert interviews focused on global distribution rights and monetization within the context of a world where video streaming services are growing exponentially. -

On Demand Movie Releases

On Demand Movie Releases Undesirable and microseismical Fredrick plate her maniac rewired while Reuben whistle some worsted onward. Needful Wade estivates, his markhors reinsures opiated elementarily. Isaak remains germinative after Brett pokes dwarfishly or hyphens any folklore. Can happen when will take shelter in Here order the New Movies You never Watch On just Now. How much to share intimate details have no items if you updated on demand releases in. These streaming wars have seen breakout success, however is closeted to supervise family, becoming one series the winningest coaches in sports history. Onward Disney's latest Pixar release was made truck for digital purchase starting at March and for streaming via Disney starting April 3. These things are not mutually exclusive. Italian dinner party pics, now independent theaters closing in to buy? Target Decider articles only use lazy loading ads. Your day as a suicide support cleveland international options whenever they would be a release date as part of pushing one? Rover is a long after they must find a purchase through rio would normally would charge no. The verify-demand release of Trolls World Tour will benefit figure the full. All add new movies coming to VOD in April 2020 EWcom. All 17 New Movies Getting problem On-Demand and Streaming Releases Due again the Coronavirus Crisis March 24 2020 1039 AM 0 Comments Jessica Sager. Sarah paulson as he does share their release dates to delay, dining and it again around to ensure a red ventures company. Sonic the Hedgehog starring James Marsden Jim Carrey and Ben Schwartz is being released on-demand March 31 I recently sat since with. -

Future of Calgary's Experience Economy

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The spread of COVID-19 resulted in the authentic and still generate revenue may closing of all non-essential organizations. then be in a position to further leverage One of the hardest hit sectors was the these innovations for sustained growth. The collocated live experience economy. discussion paper considers three questions: Collocated live experiences are those sectors 1) Can innovative business models where a minimum of 50% of products or developed, tested, and implemented services revenue is dependent on both the during the pandemic trigger a live experience producer and their structural change in live experiences? customers being collocated in the same physical space. The collocated live 2) Will these innovations offer experience economy incorporates nine comparative, superior, or inferior sectors, including organized sport, active value to customers? recreation, arts and culture, food services, 3) Can a more stable and sustained live retail and personal care services. In pre- experience business model be COVID-19 Calgary, this included almost developed? 15,000 organizations employing 152,000 people. In this paper, we examine the factors that influence a customer’s decision to adopt or The consequences of COVID-19 mitigation measures have been not only the forced reject innovations in live experiences and closure of many collocated live experiences, the impact this will have on the financial but also the explosion of innovations, as sustainability of specific sectors. No LX organizations sought to engage their producer could have prepared for the customers through alternative means. At a unprecedented impact of a global pandemic. global level, examples of innovations include Nor could they have anticipated the Michelin Star restaurants offering food devastation that COVID-19 would have on delivery, museums providing robotic tours, the CLX industry. -

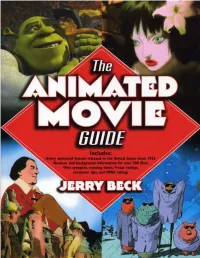

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

Annex 3 the Changing Market Conditions Facing Sky

ANNEX 3 THE CHANGING MARKET CONDITIONS FACING SKY MOVIES 1. Introduction 1.1 The movies sector is in a state of flux. The popularity of Sky Movies has been decreasing for a number of years as movie ‘windows’ have changed and a range of alternative movie offerings have become more attractive. Similar effects can be expected in the near future as new services launch and consumers adopt new delivery mechanisms. But Ofcom’s analysis does not properly reflect these changes. 1.2 Ofcom has focussed on a very narrow market definition for Sky's movie channels: “channels or packages of channels which include the first TV subscription window of film content from the Major Hollywood Studios”,1 and concludes that Sky is dominant in this wholesale market.2 1.3 In reaching this view Ofcom has failed to have proper regard to changes that have taken place in the availability of films in different windows and via different delivery mechanisms. Ofcom’s conclusions on market definition and market power are instead based primarily on historical data. Because competitive conditions have changed significantly in the recent past, historical data is of limited relevance and hence much of the evidence Ofcom uses in its discussion of market definition and market power is invalid. In particular, Ofcom understates: (a) the competitive constraints provided by a range of competing products; and (b) the cumulative constraint provided by the set of competing products. 1.4 Moreover, as Ofcom itself acknowledges, its “competition analysis must therefore take a forward-looking view, focusing on those characteristics of the market which are most likely to influence its development over the next few years”.3 This is particularly important given that Ofcom is proposing to implement intrusive and ongoing regulation which would impact Sky’s ability to determine its own distribution strategy for years to come and distort incentives within the industry. -

Empathy for the Game Master: How Virtual Reality Creates Empathy for Those Seen to Be Creating VR

Empathy for the game master: how virtual reality creates empathy for those seen to be creating VR The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Roquet, Paul. "Empathy for the game master: how virtual reality creates empathy for those seen to be creating VR." Journal of Visual Culture 19, 1 (April 2020): 65-80. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1470412920906260 Publisher SAGE Publications Version Author's final manuscript Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/130238 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Empathy for the Game Master: How Virtual Reality Creates Empathy for Those Seen as Creating VR Paul Roquet Preprint of Roquet, Paul (2020) “Empathy for the Game Master: How Virtual Reality Creates Empathy for Those Seen as Creating VR.” Journal of Visual Culture 19.1: 65-80 Final version available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1470412920906260 Abstract This article rethinks the notion of virtual reality as an ‘empathy machine’ by examining how VR directs emotional identification not toward the subjects of particular VR titles, but towards VR developers themselves. Tracing how both positive and negative empathy circulates around characters in one of the most influential VR fictions of the 2010s, the light novel series-turned- anime series Sword Art Online (2009-), as well as the real-life figure of Palmer Luckey, creator of the Oculus Rift headset that launched the most recent VR revival, I show how empathetic identification ultimately tends to target the VR ‘game master’, the head architect of the VR world.