Implications of the Referendum on EU Membership for the UK's Role in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The EU and the South Caucasus 25 Years Since Independence Nov 25, 2016 by Amanda Paul

The EU and the South Caucasus 25 Years Since Independence Nov 25, 2016 by Amanda Paul Wedged between regional powers Russia, Iran and Turkey, the South Caucasus is an extraordinarily complex region; one of the most security-challenged and fragmented regions in the world with internal and external security threats working to reinforce each other. The three South Caucasus states – Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan – are complicated even in their internal configuration. Twenty-five years since the collapse of the Soviet Union the region remains plagued by conflict, its people living in insecurity. Moreover, the region has not been politically or economically integrated. Rather Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia have integrated into a wide-range of different, sometimes opposing, organisations and alliances. The EU joined the mix of actors and organisations engaged in the South Caucasus in the early 1990‟s intensifying its engagement over the years with the three states becoming part of the EU‟s European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) and Eastern Partnership (EaP). Despite hopes that the ENP/EaP could act as transformative tool to help strengthen stability, security, democracy and bring about a more cohesive region, the results have been rather patchy. The EU has failed to carve out a clear strategy or policy for the region and with the exception of Georgia there has been little genuine will to implement serious reform. Moreover, Russia‟s annexation of Crimea and war in the Donbas in 2014 and the increasingly polarised standoff between Moscow and the West has further exacerbated the fragile security situation, further exposing the inability of the EU to guarantee or even shore-up a partner‟s security. -

Programme of the Youth, Peace and Security Conference

1 Wednesday, 23 May European Parliament – open to all participants – 12:00 – 13:00 Registration European Parliament Accreditation Centre (right-hand side of the Simone Veil Agora entrance to the Altiero Spinelli building) 13:00 – 14:00 Buffet lunch reception Members’ Restaurant, Altiero Spinelli building 14:00 – 15:00 Opening Session Room 5G-3, Altiero Spinelli building Keynote Address by Mr. Antonio Tajani, President of the European Parliament Chair Ms. Heidi Hautala, Vice-President of the European Parliament Speakers Ms. Mariya Gabriel, EU Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Ms. Ivana Tufegdzic, fYROM, EP Young Political Leaders Mr. Dereje Wordofa, UNFPA Deputy Executive Director Ms. Nour Kaabi, Tunisia, NET-MED Youth – UNESCO Mr. Oyewole Simon Oginni, Nigeria, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow 2 15:00 – 16:30 Parallel Thematic Panel Discussions Panel I Youth inclusion for conflict prevention and sustaining peace Library reading room, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Soraya Post, Member of the European Parliament Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Mr. Christian Leffler, Deputy Secretary-General, European External Action Service Mr. Amnon Morag, Israel, EP Young Political Leaders Ms. Hela Slim, France, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow Mr. MacDonald K. Munyoro, Zimbabwe, EP Young Political Leaders Facilitator Ms. Gizem Kilinc, United Network of Young Peacebuilders Panel II Young people innovating for peace Library room 128, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Barbara Pesce-Monteiro, Director, UN/UNDP Representation Office in Brussels Ms. Anna-Katharina Deininger, OSCE CiO Special Representative and OSG Focal Point on Youth and Security Ms. -

Read CDPRG Chairman Crispin Blunt's Letter to the Prime Minister

The Conservative Drug Policy Reform Group, Limited Suite 15.17 Citibase, 15th Floor Millbank Tower 21-24 Millbank, Westminster London SW1P 4QP The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP The Prime Minister 10 Downing Street London SW1A 2AA 20 November 2020 Dear Prime Minister, As Chairman of the Conservative Drug Policy Reform Group, I am writing today with a comprehensive set of recommendations prepared by the CDPRG research team, to secure the future of the UK’s cannabidiol (CBD) industry. Though nascent, this industry is already valued at £300 million and it is predicted to grow to around £1 billion by 2025, equivalent to the entirety of the UK’s herbal supplement market in 2016. I am sure you will agree with me that this projected market growth, and the jobs, investment and R&D it attracts, needs safeguarding and stimulating rather than inhibiting. This fulfilment depends on the practicality of the legislations safeguarding this burgeoning industry, which is why I am writing to strongly recommend that the UK votes in favour of recommendations to be proposed on 02 December 2020 by the World Health Organisation at the 53rd United Nations Session on the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), of which the UK is a signatory. The WHO recommends adding the following footnote to the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, to read: "Preparations containing predominantly cannabidiol and not more than 0.2 percent of delta-9- tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] are not under international control”. This harmonises with a ruling issued this week from the European Union that member states may not prohibit the marketing of CBD lawfully produced in other member states. -

LGBT+ Conservatives Annual Report 2020.Pdf

LGBT+ CONSERVATIVES TEAM April 2019 - July 20201 OFFICERS CHAIRMAN - Colm Howard-Lloyd DEPUTY CHAIRMAN - John Cope HONORARY SECRETARY - Niall McDougall HONORARY TREASURER - Cllr. Sean Anstee CBE VICE-CHAIRMAN CANDIDATES’ FUND - Cllr. Scott Seaman-Digby VICE-CHAIRMAN COMMUNICATIONS - Elena Bunbury (resigned Dec 2019) VICE-CHAIRMAN EVENTS - Richard Salt MEMBERSHIP OFFICER - Ben Joce STUDENT OFFICER - Jason Birt (resigned Sept 2019) GENERAL COUNCIL Cllr. Andrew Jarvie Barry Flux David Findlay Dolly Theis Cllr. Joe Porter Owen Meredith Sue Pascoe Xavier White REGIONAL COORDINATORS EAST MIDLANDS - David Findlay EAST OF ENGLAND - Thomas Smith LONDON - Charley Jarrett NORTH EAST - Barry Flux SCOTLAND - Andrew Jarvie WALES - Mark Brown WEST MIDLANDS - John Gardiner YORKSHIRE AND THE HUMBER - Cllr. Jacob Birch CHAIRMAN’S REPORT After a decade with LGBT+ Conservatives, more than half of them in the chair, it’s time to hand-on the baton I’m not disappearing completely. One of my proudest achievements here has been the LGBT+ Conservatives Candidates’ Fund, which has supported so many people into parliament and raised tens of thousands of pounds. As the fund matures it is moving into a new governance structure, and I hope to play a role in that future. I am thrilled to be succeeded by Elena Bunbury. I know that she will bring new energy to the organisation, and I hope it will continue to thrive under her leadership. I am so grateful to everyone who has supported me on this journey. In particular Emma Warman, Matthew Green and John Cope who have provided wise counsel as Deputy Chairman. To Sean Anstee who has transformed the finances of the organisation. -

The Prime Minister, HC 833

Liaison Committee Oral evidence: The Prime Minister, HC 833 Tuesday 20 December 2016 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 20 Dec 2016. Watch the meeting Members present: Mr Andrew Tyrie (Chair); Hilary Benn; Mr Clive Betts; Crispin Blunt; Andrew Bridgen; Sir William Cash; Yvette Cooper; Meg Hillier; Mr Bernard Jenkin; Dr Julian Lewis; Stephen Metcalfe; Mr Laurence Robertson; Dame Rosie Winterton; Pete Wishart; Dr Sarah Wollaston; Mr Iain Wright. Questions 1-129 Witness [I]: Rt Hon Mrs Theresa May Examination of witness Witness: Rt Hon Mrs Theresa May Q1 Chair: Prime Minister, thank you very much for coming to give evidence to us this afternoon. We are very grateful, and I think Parliament is also very grateful, that you are agreeing to do these sessions. Could I just have confirmation that you are going to continue the practice of your predecessor of three a year? Mrs May: Yes, indeed, Chairman. I am happy to do three attendances at this Committee a year. Q2 Chair: Logically, bearing in mind the very big events likely to take place at the end of March, it might be sensible to push scrutiny of the triggering, or proposed triggering, of article 50, and any accompanying Government documents, to after the spring recess. Then we will have two meetings: one right at the beginning and one towards the end of the summer session. Mrs May: That may very well be sensible, Chairman. I suggest that perhaps the Clerk and my office will be able to talk about possible dates. Obviously the Committee will have a view as to when they wish to do it. -

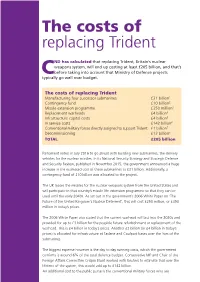

The Costs of Replacing Trident

The costs of replacing Trident ND has calculated that replacing Trident, Britain’s nuclear weapons system, will end up costing at least £205 billion, and that’s Cbefore taking into account that Ministry of Defence projects typically go well over budget. The costs of replacing Trident Manufacturing four successor submarines £31 billion 1 Contingency fund £10 billion 2 Missile extension programme £350 million 3 Replacement warheads £4 billion 4 Infrastructure capital costs £4 billion 5 In service costs £142 billion 6 Conventional military forces directly assigned to support Trident £1 billion 7 Decommissioning £13 billion 8 TOTAL £205 billion Parliament voted in July 2016 to go ahead with building new submarines, the delivery vehicles for the nuclear missiles. In its National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review, published in November 2015, the government announced a huge increase in the estimated cost of these submarines to £31 billion. Additionally, a contingency fund of £10 billion was allocated to the project. The UK leases the missiles for the nuclear weapons system from the United States and will participate in that country’s missile life extension programme so that they can be used until the early 2040s. As set out in the government’s 2006 White Paper on ‘The Future of the United Kingdom's Nuclear Deterrent’ , this will cost £250 million, or £350 million in today’s prices. The 2006 White Paper also stated that the current warhead will last into the 2020s and provided for up to £3 billion for the possible future refurbishment or replacement of the warhead. -

Incomplete Hegemonies, Hybrid Neighbours: Identity Games and Policy Tools in Eastern Partnership Countries Andrey Makarychev

Incomplete Hegemonies, Hybrid Neighbours: Identity games and policy tools in Eastern Partnership countries Andrey Makarychev No 2018/02, February 2018 Abstract This paper applies the concepts of hegemony and hybridity as analytical tools to help understand the structural changes taking place within the Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries and beyond. The author points to the split identities of many post-Soviet societies and the growing appeal of solutions aimed at balancing Russia’s or the EU’s dominance as important factors shaping EaP dynamics. Against this background, he explores how the post-Soviet borderlands can find their place in a still hypothetical pan-European space, and free themselves from the tensions of their competing hegemons. The EaP is divided into those countries that signed Association Agreements with the EU and those preferring to maintain their loyalty to Eurasian integration. Bringing the two groups closer together, however, is not beyond policy imagination. The policy-oriented part of this analysis focuses on a set of ideas and schemes aimed at enhancing interaction and blurring divisions between these countries. The author proposes five scenarios that might shape the future of EaP countries’ relations with the EU and with Russia: 1) the conflictual status quo in which both hegemonic powers will seek to weaken the position of the other; 2) trilateralism (EU, Russia plus an EaP country), which has been tried and failed, but still is considered as a possible option by some policy analysts; 3) the Kazakhstan-Armenia model of diplomatic advancement towards the EU, with some potential leverage on Russia; 4) deeper engagement by the EU with the Eurasian Economic Union, which has some competences for tariffs and technical standards; and 5) the decoupling of security policies from economic projects, which is so far the most difficult option to foresee and implement in practice. -

Defence and Security After Brexit Understanding the Possible Implications of the UK’S Decision to Leave the EU Compendium Report

Defence and security after Brexit Understanding the possible implications of the UK’s decision to leave the EU Compendium report James Black, Alex Hall, Kate Cox, Marta Kepe, Erik Silfversten For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1786 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cambridge, UK © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: HMS Vanguard (MoD/Crown copyright 2014); Royal Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon FGR4, A Chinook Helicopter of 18 Squadron, HMS Defender (MoD/Crown copyright 2016); Cyber Security at MoD (Crown copyright); Brexit (donfiore/fotolia); Heavily armed Police in London (davidf/iStock) RAND Europe is a not-for-profit organisation whose mission is to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org www.rand.org/randeurope Defence and security after Brexit Preface This RAND study examines the potential defence and security implications of the United Kingdom’s (UK) decision to leave the European Union (‘Brexit’). -

Italy in the European Union.Pdf

Italy in the European Union POL S 346/JSIS A 302: Europeanizaon of poli:cal systems Spring Term 2017 Frank Wendler May 23, 2017 Italy in the EU From top leL clockwise to center: Signing of the Treaty of Rome founding the EEC in 1957, former Italian PM Silvio Berlusconi, EU Foreign Policy Representave Federica Mogherini, 5-Star Movement leader Beppe Grillo, a scene with refugees on Lampedusa, portal of Italian bank Monte dei Paschi and President Obama with Italian PM Maeo Renzi in 2016. Three theses about Italy’s membership in the European Union (1) Membership in the European Union has worked as an almost con:nuous pressure for economic and poli:cal reform in Italy. (2) These economic and poli:cal reforms are hard to realize because of the specific structure of Italy’s poli:cal system, which combines a strong ins:tu:onal consensus democracy with high poli:cal polarizaon. (3) The result is that Europeanizaon has increased the centrifugal tendencies of Italian poli:cs, leaving three main op:ons for a resolu:on: an:-elite populism, technocrac government or ins:tu:onal reform. ‘Gli Esami Non Finiscono Mai’ Vincent della Sala ‘Gli Esami Non Finiscono Mai’: The EU as an ininite test of Italy’s modernization • Italy as a founding member of the EEC 1957 • Post-war stabiliziaon and rehabilitaon • Par:cipaon in the Single Market • EC Single Market as a test of Italy’s compe::veness • Membership in the Eurozone • Far-reaching economic and social reform passed to meet membership criteria • Link between EU Membership and domes:c poli:cal reform • 2016 -

Local Needs Issue 3

Local Needs Local Health issue 3 January 2009 Reviewing the way the Trust is shaped Welcome Project support Last summer, we announced plans with our strategic PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC) has been appointed to health authority, NHS London, to review the way the offer expert advice to the Local Needs, Local Health review. Trust is managed. This is a briefing to update staff, Their role includes helping the project partners to volunteers, patients, local people and other stakeholders understand the financial and clinical implications of the on the latest news from the Local Needs, Local Health three proposed options (status quo, de-merger and review. divestment). They will also help the Trust involve staff, volunteers and other stakeholders in the review process. Involving staff Samantha Jones Plans are being developed to ensure as many staff and Chief Executive volunteers, both clinical and non-clinical, are able to get involved with Local Needs, Local Health, giving them a chance to help shape the review. Project Board All Trust consultants have already been invited to attend a seminar on 23 January, 1pm – 5pm, at Epsom Racecourse. Consultants are asked to confirm their attendance by The first meeting of the Local Needs, Local Health Project emailing [email protected]. Board will take place on 22 January. The Board, which is made up of representatives from the five partner Events for other staff and volunteers will be publicised shortly. organisations, will be asked to formally agree how the review will be run (called the Terms of Reference) and how it will be managed (known as the governance structure). -

Post DIGITAL REVOLUTION for the Many, Not for the Few

10 # # The 10 WINTER 2018-2019 3.00 € Progressive Post DIGITAL REVOLUTION for the many, not for the few SPECIAL COVERAGE #EP2019 How could the Left recover? NEXT DEMOCRACY NEXT GLOBAL NEXT SOCIAL Baby-boomers vs Millennials Bolsonaro, the Left Social housing: back on and Europe the progressive agenda NEXT ECONOMY NEXT LEFT NEXT ENVIRONMENT FOLLOW UP End of Quantitative easing - Culture to rebuild Free public transport Global Compact for Safe, Scenarios for the real economy faith in democracy everywhere Orderly and Regular Migration Quarterly : December - January - February www.progressivepost.eu ProgressiveThe Post Europeans share a common history and future, but their ideas and ideals still need a public space. The Progressive Post The truly European progressive opinion magazine that gathers world-renowned experts, to offer a platform informing the public about the issues facing Europe today. The Progressive Post The magazine is published in two languages: English and French. We’ve got also partnerships with The Fabian Review (UK) and TEMAS (ES) Progressivepost.eu + @FEPS-Europe Daily analysis and opinion to supplement the print edition With the support of the European Parliament PUBLICATION DIRECTOR Ernst Stetter EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Alain Bloëdt EDITORS Karine Jehelmann, Olaf Bruns EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Ania Skrzypek, David Rinaldi, Vassilis Ntousas, Maria Freitas, Hedwig Giusto, Charlotte Billingham, Lisa Kastner, Laeticia Thissen, Justin Nogarède TRANSLATORS Ben O'Donovan, Amandine Gillet, Françoise Hoffelinck, Eurideas Language Experts PROOFREADING Louise Hanzlik, Stéphanie Bessalem COORDINATION & GRAPHIC DESIGN www.triptyque.be PHOTO CREDITS Shutterstock, The EU’s Audiovisual Media Services COVER ILLUSTRATION Peter Willems - Vec-Star COPYRIGHT © FEPS – Foundation for European Progressive Studies N°10 - Winter 2018 - 19 ISSN 2506-7362 EDITORIAL Digital: revolution without revolt by Maria Joao Rodrigues, FEPS President This edition focuses on the digital revolution. -

The Future Operations of BBC Monitoring

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee The future operations of BBC Monitoring Fifth Report of Session 2016–17 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 25 October 2016 HC 732 Published on 29 October 2016 by authority of the House of Commons The Foreign Affairs Committee The Foreign Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Crispin Blunt MP (Conservative, Reigate) (Chair) Mr John Baron MP (Conservative, Basildon and Billericay) Ann Clwyd MP (Labour, Cynon Valley) Mike Gapes MP (Labour (Co-op), Ilford South) Stephen Gethins MP (Scottish National Party, North East Fife) Mr Mark Hendrick MP (Labour (Co-op), Preston) Adam Holloway MP (Conservative, Gravesham) Daniel Kawczynski MP (Conservative, Shrewsbury and Atcham) Yasmin Qureshi MP (Labour, Bolton South East) Andrew Rosindell MP (Conservative, Romford) Nadhim Zahawi MP (Conservative, Stratford-on-Avon) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/facom and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry publications page of the Committee’s website. Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are Chris Stanton (Clerk), Nick Beech (Second Clerk), Dr Ariella Huff (Senior Committee Specialist), Ashlee Godwin (Committee Specialist), Nicholas Wade (Committee Specialist), Clare Genis (Senior Committee Assistant), Su Panchanathan (Committee Assistant), Amy Vistuer (Committee Assistant), and Estelle Currie (Media Officer).