1. Victor Turner Lists These Three Aspects of Culture As “Exception- Ally Well Endowed with Ritual Symbols and Beliefs of Non-Structural Type” ( Dramas 231)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Introducing Yemoja

1 2 3 4 5 Introduction 6 7 8 Introducing Yemoja 9 10 11 12 Solimar Otero and Toyin Falola 13 14 15 16 17 18 Mother I need 19 mother I need 20 mother I need your blackness now 21 as the august earth needs rain. 22 —Audre Lorde, “From the House of Yemanjá”1 23 24 “Yemayá es Reina Universal porque es el Agua, la salada y la dul- 25 ce, la Mar, la Madre de todo lo creado / Yemayá is the Universal 26 Queen because she is Water, salty and sweet, the Sea, the Mother 27 of all creation.” 28 —Oba Olo Ocha as quoted in Lydia Cabrera’s Yemayá y Ochún.2 29 30 31 In the above quotes, poet Audre Lorde and folklorist Lydia Cabrera 32 write about Yemoja as an eternal mother whose womb, like water, makes 33 life possible. They also relate in their works the shifting and fluid nature 34 of Yemoja and the divinity in her manifestations and in the lives of her 35 devotees. This book, Yemoja: Gender, Sexuality, and Creativity in the 36 Latina/o and Afro-Atlantic Diasporas, takes these words of supplica- 37 tion and praise as an entry point into an in-depth conversation about 38 the international Yoruba water deity Yemoja. Our work brings together 39 the voices of scholars, practitioners, and artists involved with the inter- 40 sectional religious and cultural practices involving Yemoja from Africa, 41 the Caribbean, North America, and South America. Our exploration 42 of Yemoja is unique because we consciously bridge theory, art, and 43 xvii SP_OTE_INT_xvii-xxxii.indd 17 7/9/13 5:13 PM xviii Solimar Otero and Toyin Falola 1 practice to discuss orisa worship3 within communities of color living in 2 postcolonial contexts. -

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

The Four Paths to Publishing

THE FOUR PATHS TO PUBLISHING Revolutionary changes and unprecedented opportunities in publishing have established four clear paths that authors follow to achieve their publishing goals. by Keith Ogorek Senior Vice President of Marketing and Product Development Author Solutions, Inc. The past four years have brought about more upheaval in the publishing industry than the previous 400 years combined. From the time Gutenberg invented the printing press until the introduction of the paperback about 70 years ago, there weren’t many groundbreaking innovations. However, in the last few years, the publishing world has undergone an indie revolution similar to what occurred in the film and music industries. With the introduction of desktop publishing, print-on-demand technology, and the Internet as a direct-to-consumer distribution channel, publishing became a service consumers could purchase, instead of an industry solely dependent on middlemen (agents) and buyers (traditional publishers). In addition, the exponential growth of e-books and digital readers has accelerated change, because physical stores are no longer the only way for authors to connect with readers. While these changes have made now the best time in history to be an author, they have also made it one of the most confusing times to be an author. Not that long ago, there was only one way to get published: find an agent; hope he or she would represent you; pray they sell your book proposal to a publisher; trust the publisher to get behind the book and believe in the project; and hope that readers would go to their local bookstore and buy your book. -

Live in Rio Queen

Live in rio queen Queen - Live in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil [Rock in Rio Festival ] - January 19, | p Subscribe to the official Queen channel Here The Works Tour of / was. The English rock band Queen was well known for its live musical acts. Diverse musical .. The Works Tour in / was one of Queen's largest tours and included the Brazil Rock in Rio festival—in which they appeared on stage at two s · s · s · s. Queen - Live in Rio è una VHS dei Queen, pubblicata nel Indice. [nascondi]. 1 Il video; 2 Tracce; 3 Curiosità; 4 Formazione. Gruppo; Altri musicisti Il video · Tracce · Curiosità · Formazione. Documentary · British rock's greatest entertainers play to more than , people in Rio, Brazil. Queen headlined two nights of the day Rock In Rio festival in , the biggest music festival in history to date. Also headlining two nights. This one hour film finds Queen at the Rock In Rio festival in Brazil in January , performing over two. Get the Queen Setlist of the concert at Cidade do Rock, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil on January 18, from the The Works Tour and other Queen. Find album reviews, stream songs, credits and award information for Live in Rio [Video] - Queen on AllMusic - - In January of , Queen performed at the. Find a Queen - Live In Rio first pressing or reissue. Complete your Queen collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Buy Queen Live IN Rio from Amazon's Movies Store. Everyday low prices and free delivery on eligible orders. Playlist:Tie Your Mother DownSeven Years Of RhyeKeep Yourself AliveLiarIt´s A Hard LifeNow I´m HereIs This The World We CreatedLove Of My LifeBrighton. -

Original Blessing

Original Blessing Original Blessing Putting Sin in Its Rightful Place Danielle Shroyer Fortress Press Minneapolis ORIGINAL BLESSING Putting Sin in Its Rightful Place Copyright © 2016 Fortress Press. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Visit http://www.augsburgfortress.org/copyrights/ or write to Permissions, Augsburg Fortress, Box 1209, Minneapolis, MN 55440. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright (c) 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design: Brad Norr Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Print ISBN: 978-1-4514-9676-5 eBook ISBN: 978-1-5064-2029-5 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z329.48-1984. Manufactured in the U.S.A. This book was produced using Pressbooks.com, and PDF rendering was done by PrinceXML. Life’s great happiness is to be convinced we are loved. —Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Contents Introduction: Elevator Pitch ix I. AWAKENING TO BLESSING Blessing is Like Bulletproof Glass 3 Blessing is God’s Prerogative 11 Original Sin is Unnecessary and Unhelpful 25 A Tale of Two Boxes and a Golden Thread 47 II. REVISITING THE GARDEN Let’s All Take a Deep Breath about Genesis 59 God’s Actions Speak Loudly of Blessing 75 You Can’t Rush Happily Ever After 87 III. -

The House of Oduduwa: an Archaeological Study of Economy and Kingship in the Savè Hills of West Africa

The House of Oduduwa: An Archaeological Study of Economy and Kingship in the Savè Hills of West Africa by Andrew W. Gurstelle A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Carla M. Sinopoli, Chair Professor Joyce Marcus Professor Raymond A. Silverman Professor Henry T. Wright © Andrew W. Gurstelle 2015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I must first and foremost acknowledge the people of the Savè hills that contributed their time, knowledge, and energies. Completing this dissertation would not have been possible without their support. In particular, I wish to thank Ọba Adétùtú Onishabe, Oyedekpo II Ọla- Amùṣù, and the many balè,̣ balé, and balọdè ̣that welcomed us to their communities and facilitated our research. I also thank the many land owners that allowed us access to archaeological sites, and the farmers, herders, hunters, fishers, traders, and historians that spoke with us and answered our questions about the Savè hills landscape and the past. This dissertion was truly an effort of the entire community. It is difficult to express the depth of my gratitude for my Béninese collaborators. Simon Agani was with me every step of the way. His passion for Shabe history inspired me, and I am happy to have provided the research support for him to finish his research. Nestor Labiyi provided support during crucial periods of excavation. As with Simon, I am very happy that our research interests complemented and reinforced one another’s. Working with Travis Williams provided a fresh perspective on field methods and strategies when it was needed most. -

THE 14TH ANNUAL BEST BOOK AWARDS Sponsored by American Book Fest

THE 14TH ANNUAL BEST BOOK AWARDS Sponsored by American Book Fest Full Results Listing by Category Congratulations to all of the Winners & Finalists of the 2017 Best Book Awards. AMERICAN BOOK FEST IS PROUD TO PRESENT THE 2017 BEST BOOK AWARD WINNING TITLES Animals/Pets: General Dogs, The Family We Choose by Melanie Steele, photography by Holli Murphy Starbooks/Lydia Inglett Publishing 978-1-938417-32-0 Animals/Pets: Narrative Non-Fiction The Chicken Who Saved Us: The Remarkable Story of Andrew and Frightful by Kristin Jarvis Adams Behler Publications 978-1-941887-00-4 Anthologies: Non-Fiction Breaking Sad: What to Say After Loss, What Not to Say, and When to Just Show Up edited by Shelly Fisher & Jennifer Jones She Writes Press 978-1-63152-242-0 Art The Noise Beneath the Apple by Heather Jacks Self-Published 978-0988951709 Autobiography/Memoir Holding the Net: Caring for My Mother on the Tightrope of Aging by Melanie P. Merriman Green Writers Press 978-0998701226 Best Cover Design: Fiction The Shores of Our Souls by Kathryn Brown Ramsperger Touchpoint Press 978-14-946920-03 Best Cover Design: Non-Fiction The Map to Abundance: The No-Exceptions Guide to Creating Money, Success & Bliss by Boni Lonnsburry Inner Art Inc. 978-1-941322-14-7 Best Interior Design The Ultimate Guide To Champagne by Liz Palmer Liz Palmer Media Group Inc. 978-0991894635 Best New Fiction Girl in the Afternoon by Serena Burdick St. Martin's Press 978-1250082671 Best New Non-Fiction A Garden for the President: A History of the White House Grounds by Jonathan Pliska -

A Walk Through the Gallery 5

A WALK THROUGH THE GALLERY MARGARET PLASS The new African Gallery has been designed to exhibit, simply and honestly, a selection of sculptures from our permanent collections. Proudly we present them as works of art; where possible they are arranged in tribal groups for convenience and comparative study. They are labeled briefly and clearly. Here are the materials from which our visitors may form a just view of the special characteristics and merits of Negro art. For more than half a century our Museum has been enriched by acces- sions of African sculpture, mainly by purchase and partly by gifts, to the end that our permanent collections are the largest and most varied in style in America. The following descriptive notes are not to be construed as an attempt at a catalogue of the exhibition; the serious student may have access to fully documented formal catalogues should he apply to the Museum staff. In Dr. Coon's introduction he has given us the anthropological and ethno- grapbical background of the people who produced this art, working within the framework of their tribal traditions. Here in this book, with their photographs, are small synopses of what we know of these sculptures, and what we guess. We all have conscious, and sometimes unconscious, difficulty in understanding such works of art; the philosophical barrier that lies in the way of full appreciation is almost too difficult to hurdle. Many writers have tried to explain the magico-religious significance, the strength and directness of African art; few have succeeded. Perhaps these notes are mere hints and suggestions, but we hope that they may sometimes be stimulating as well as factual. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

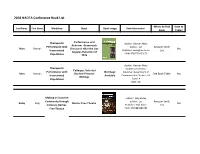

2018 NADTA Conference Book List

2018 NADTA Conference Book List Where to Find View at Last Name First Name Workshop Book Book Image Book Information Book Table? Performance and Therapeutic Author: Kamran Afary Activism: Grassroots Performance with Edition: 1st Amazon Smile Afary Kamran Discourse After the Los Yes Publisher: Lexington Books Incarcerated Angeles Rebellion of List ISBN: 9780739133576 Populations 1992 Author: Kamran Afary Therapeutic Volume 13 Fall 2017 Colloquy: Selected Performance with No Image Publisher: Department of Afary Kamran Student-Prisoner See Book Table Yes Communication Studies, Cal Incarcerated Writings Available Populations State LA ISBN: NA Making an Inclusive Author: Sally Bailey Community through Edition: 1st Amazon Smile Bailey Sally Barrier-Free Theatre Yes Inclusive, Barrier- Publisher: Idyll Arbor List Free Theatre ISBN: 9781882883783 Author: Anne Fliotsos and Making an Inclusive Gail Medford Community through New Direction in Edition: 1st Amazon Smile Bailey Sally Yes Inclusive, Barrier- Teaching Theatre Arts Publisher: Palgrave List Free Theatre Macmillan ISBN: 9783319897660 Author: Adam Blatner and Making an Inclusive Interactive and Daniel Wiener Community through Improvisational Drama: Amazon Smile Bailey Sally Edition: 1st Yes Inclusive, Barrier- Varieties of Applied List Publisher: iUniverse, Inc. Theatre Free Theatre ISBN: 9780595417506 Making an Inclusive Author: Grace Schuchner and Domingo Ferrandis Community through Amazon Smile Bailey Sally Dramaterapia Edition: 1st Yes Inclusive, Barrier- List Publisher: Letra Viva Free -

Indigenous Environmental Rights, Participation and Lithium Mining In

Indigenous Environmental Rights, Participation and Lithium Mining in Argentina and Bolivia: A Socio-Legal Analysis Helle Abelvik-Lawson A thesis submitted for the degree of PhD School of Law and Human Rights Centre and Interdisciplinary Studies Centre University of Essex Date of submission: May 2019 For my family, on Earth and in Heaven. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I must thank my incredible husband-to-be Dauji Thomas, truly one of the world’s most amazing individuals, and without whom absolutely none of this would have been possible. Thank you for being there for me, and your understanding, through the hard times and the good. I am in fact wholly indebted to all my family, particularly my amazing Mama for showing me how to keep going even when the going is tough, and of course my stepdad Dean. Thanks also to Guy for giving me a wonderful place to study in the stunning Essex countryside. To my brother Frase, and Dix and Cos: I am so glad to have you all in my life. I am deeply grateful for the support of my dedicated, and encouraging and insightful supervisors, Professor Karen Hulme and Dr Jane Hindley, who went beyond the call of duty to help me achieve my aims. At Essex and elsewhere, I am incredibly fortunate to count a number of academics and experts in the field as mentors and friends, who continually pique my curiosities and inspire me to continue working in human rights. Dr Damien Short, Professor Colin Samson, Dr Corinne Lennox, Dr Julian Burger – thank you for showing me how it’s done.