Tidal Reservoir Inlet Bridge HAER No. DC-9A W<33Fc Potomae Park At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potomac Flats.Pdf

Form 10-306 STATE: (Oct. 1972) NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NFS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) ———m COMMON: East and West Potomac Parks AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: area bounded by Constitution Avenue, 17th Street, Indepen dence Avenue, Washington Channel, Potomac River and Rock Creek Park CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL ^ongressman Washington Walter E. Fauntroy, D.C. STATE: CODE COUNTY: District of Columbia 11 District of Columbia 001 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC [X] District Q Building |XJ Public Public Acquisition: CD Occupied Yes: QSite CD Structure CD Private CD In Process I | Unoccupied I | Restricted CD Object CD Both I | Being Considered [ | Preservation work Qg) Unrestricted in progress LDNo PRESENT USE (Check One of More as Appropriate) I | Agricultural [XJ Government ffi Park 1X1 Transportation | | Commercial CD Industrial CD Private Residence CD Other (Specify) CD Educational CD Military [ | Religious I | Entertainment [~_[ Museum I | Scientific National Park Service, Department of the Interior REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) STREET AND NUMBER: National Capital Parks 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. CITY OR TOWN: CODE Washington COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: None exists—parks are reclaimed land TITLE OF SURVEY: National Park Service survey in compliance with Executive Order 11593 DATE OF SURVEY: [29 Federal CD State CD County CD Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: 09 National Capital Parks STREET AND NUMBER: 1100 Ohio Drive, S.W. Cl TY OR TOWN: Washington District of Columbia 11 ©-©--- - - "- © - - _--_ -.- _---..-- . _ - B& Exc9\\en* [~~| Good- v'Q FVir - "^Q Deteriorated : - fH Ruins "-': - PI Unexposed : CONDWIOK -=."'-". -

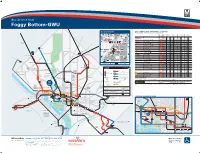

Bus Service from Foggy Bottom-GWU

Bus Service from Foggy Bottom-GWU Silver Spring BUS BOARDING MAP BUS SERVICE AND BOARDING LOCATIONS The table shows approximate minutes between buses; check schedules for full details 1/4 mile Best radius West End walking Branch Western MONDAY TO FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY distance Ritz-Carlton e Library v BOARD AT One A L St e L St Washington ir ROUTE DESTINATION BUS STOP AM RUSH MIDDAY PM RUSH EVENING DAY EVENING DAY EVENING t t h s S Eastern Ave S Avenue Pe Circle p George t t h n d m n t r t S s Suites y a S 4 Washington lv 3 a A H S METROBUS h 2 2 n d t t ia University A D n s 5 v e ew 2 1 2 Hospital N 2 The hington C 2 as ir 30N 30S 33 Friendship Heights m 10-20 10-20 7-15 15-30 10-20 15-30 10-20 15-30 Melrose J W CD George 30N 36 Naylor Rd m 15-25 20 15 15-30 20-30 20-30 30 30 29 K St Washington K St 29 BF Bethesda Statue C International 30S 32 Southern Ave m 15-25 20 10-15 15-30 20-30 20-30 20-40 20-40 Finance BF P Corporation t e B nn C s 31 Friendship Heights m 30 30 12-20 30 30 30 30 30 ylv Takoma s a DF nia w George Washington Western Ave Queen Annes Ln Av o University Hospital e n 31 32 36 Potomac Park 3-6 6-14 7-20 10-20 10-15 12-30 12-20 30 S I St E L1 Chevy Chase Circle F 33 Federal Triangle B 5-15 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 Georgia Ave I St e I St Military Rd v 38B Ballston-MU m 12-25 20 15 20-30 30 30 30 30 A Connecticut Ave Riggs Rd Foggy Bottom- CD re E 31 t GWU Inn hi S s GWU 38B Farragut N&W 12 20 9-15 20-30 30 30 30 30 33 h m Military Rd t mp 5 A a 80 2 Academic & Marvin 30N H Doubletree 16th St 14th St Fort Totten Galloway -

Building Stones of the National Mall

The Geological Society of America Field Guide 40 2015 Building stones of the National Mall Richard A. Livingston Materials Science and Engineering Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA Carol A. Grissom Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, 4210 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA Emily M. Aloiz John Milner Associates Preservation, 3200 Lee Highway, Arlington, Virginia 22207, USA ABSTRACT This guide accompanies a walking tour of sites where masonry was employed on or near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It begins with an overview of the geological setting of the city and development of the Mall. Each federal monument or building on the tour is briefly described, followed by information about its exterior stonework. The focus is on masonry buildings of the Smithsonian Institution, which date from 1847 with the inception of construction for the Smithsonian Castle and continue up to completion of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. The building stones on the tour are representative of the development of the Ameri can dimension stone industry with respect to geology, quarrying techniques, and style over more than two centuries. Details are provided for locally quarried stones used for the earliest buildings in the capital, including A quia Creek sandstone (U.S. Capitol and Patent Office Building), Seneca Red sandstone (Smithsonian Castle), Cockeysville Marble (Washington Monument), and Piedmont bedrock (lockkeeper's house). Fol lowing improvement in the transportation system, buildings and monuments were constructed with stones from other regions, including Shelburne Marble from Ver mont, Salem Limestone from Indiana, Holston Limestone from Tennessee, Kasota stone from Minnesota, and a variety of granites from several states. -

Staff Recommendation

STAFF RECOMMENDATION NCPC File No. 7060 THE NATIONAL MALL NATIONAL MALL PLAN Washington, DC Submitted by the National Park Service November 23, 2010 Abstract The National Park Service has submitted the National Mall Plan for the management and stewardship of the land in its jurisdiction on the National Mall. The plan is a framework for future decision-making and implementation of physical improvements for the protection of the National Mall’s renowned natural and cultural resources, new visitor amenities and services, additional accommodations for First Amendment demonstrations and special events, better- linked circulation in a range of modes, accessibility throughout the Mall, additional opportunities for active and passive recreation, and improved visitor information and education. The National Park Service’s goal for the National Mall is that it be a model in sustainable urban park development, resource protection, and management. Commission Action Requested by Applicant Approval of the National Mall Plan, pursuant to 40 U.S.C. § 8722(b)(1) and (d)). Executive Director’s Recommendation The Commission: Approves the National Mall Plan, as shown on NCPC Map File No. 1.41(78.00)43205. Notes that: • The National Mall Plan is based on the Preferred Alternative presented and analyzed in the National Park Service’s Final Environmental Impact Statement, Record of Decision, and Section 106 Programmatic Agreement. NCPC File No. 7060 Page 2 • Additional compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act and the National Historic Preservation Act will be required for the development and implementation of many of the National Mall Plan’s proposed projects, and that the siting and design of individual projects are subject to the Commission’s review and approval. -

National Mall & Memorial Parks

COMPLIMENTARY $2.95 2017/2018 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS NATIONAL MALL & MEMORIAL PARKS ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS This summer, Yamaha launches a new Star motorcycle designed to help you journey further…than you ever thought possible. To see the road ahead, visit YamahaMotorsports.com/Journey-Further Some motorcycles shown with custom parts, accessories, paint and bodywork. Dress properly for your ride with a helmet, eye protection, long sleeves, long pants, gloves and boots. Yamaha and the Motorcycle Safety Foundation encourage you to ride safely and respect the environment. For further information regarding the MSF course, please call 1-800-446-9227. Do not drink and ride. It is illegal and dangerous. ©2017 Yamaha Motor Corporation, U.S.A. All rights reserved. BLEED AREA TRIM SIZE WELCOME LIVE AREA Welcome to our nation’s capital, Wash- return trips for you and your family. Save it ington, District of Columbia! as a memento or pass it along to friends. Zion National Park Washington, D.C., is rich in culture and The National Park Service, along with is the result of erosion, history and, with so many sites to see, Eastern National, the Trust for the National sedimentary uplift, and there are countless ways to experience Mall and Guest Services, work together this special place. As with all American to provide the best experience possible Stephanie Shinmachi. Park Network editions, this guide to the for visitors to the National Mall & Me- 8 ⅞ National Mall & Memorial Parks provides morial Parks. information to make your visit more fun, memorable, safe and educational. -

Potomac River Tidal Basin L'enfant Dev

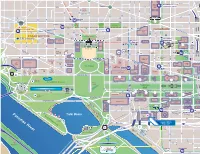

S S St. Matthew's S Cathedral 11th 11th Jefferson Pl 12th 10th Ridge St Morgan St Washington MT. VERNONONN SQ.S / 7THH ST- Thomas Circle Convention CONVENTIONON CENTERTE M St M St Center National Geographic Society P Desales St 17th St Sumner Row L St 16th St 16th 18th St 13th St 13th 14th St 15th St L St L St FARRAGUTRR NORTHRT Mt Vernon Washington Square t K St City Museum Circle McPherson FARRAGUTAR WESTT Farragut 4th St Square Square Franklin Park GW HOSPITAL I St I St (EYE) New York Ave CHINATOWN Massachusetts FOGGYFOO BOTTOM-OT GWU 20th St 19th St MCPHERSONRS Old Convention I St Pennsylvania SQUAREUAARE Center 25th St I St (closed) Ave 17th St 7th St H St 8th St Ave Decatur 9th St House H St FOGGY BOTTOM Jackson Pl Lafayette Square National Renwick Madison Pl Museum H St 15th St G.W. University Gallery of Women GALLERYYYP PL.-P General International in the Arts Accounting Monetary World METROTR Martin Luther King CHINATOWNOWNWNW Office Fund Bank CENNTTER Memorial Library 21st St 21st 24th St 23rd St G St 22nd St G St MCI CENTER Executive Jewish Office Building Treasury Historical Department St th National Building Society of 11 12th St St 10th Museum Greater Washington The White House National F St Octagon Law Enforcement Virginia Ave Theatre Warner Memorial General Museum Theatre Services Ford's Int'l Spy JUDDID ARY Admin Theatre Museum SSQ E Freedom E St E St Corcoran Plaza Gallery of Art Shakespeare Wilson J Edgar Hoover Theatre E St 8th St D St 5th St Building Building (FBI) 6th St Office of Personal White House Pennsylvania Ave Management Red Cross Visitor Center Int'l D St Navy Dept. -

Swimmable Potomac Campaign

SWIMMABLE POTOMAC CAMPAIGN P O T O M A C R I V E R K E E P E R N E T W O R K M A Y 2 0 1 9 - O C T O B E R 2 0 1 9 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 CITIZEN SCIENCE WATER QUALITY MONITORING RESULTS - 2019 8 CITIZEN SCIENCE VOLUNTEER MONITORING PROGRAM 10 SEA DOG FLOATING LABORATORY 11 LOOKING AHEAD TO 2020 12 WHAT CAN YOU DO TO HELP? 14 TECHNICAL APPENDIX 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Potomac River flows through the heart of our nation’s capital on its course to the Chesapeake Bay, providing drinking water for six million people and countless recreational opportunities to millions of residents and visitors drawn to its beauty. The popularity of the Nation’s River for recreation continues to grow, as anyone who has been to the DC waterfront lately can plainly see. People are coming to the river to kayak, row, fish, stand up paddleboard, and swim, encouraged by easy access, beautiful riverfront parks and public boathouses. The one key thing that’s been missing until now is accurate, timely data on whether the Potomac is clean enough to swim and paddle in. To answer the call, Potomac Riverkeeper (PRK) launched its Citizen Science Water Quality Monitoring Program in 2019. Water samples collected weekly by volunteers at ten locations are analyzed in certified labs, including on our flagship vessel Sea Dog, and shared with the public every Friday on the free SWIMGuide app. While water quality has improved dramatically since the passage of the Clean Water Act nearly fifty years ago, the Potomac is still burdened with discharges of untreated sewage and polluted stormwater from D.C. -

Potomac Park

46 MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN EDAW Enhance the Waterfront Experience POTOMAC PARK Potomac Park can be reimagined as a unique Washington destination: a prestigious location extending from the National Mall; a setting of extraordinary beauty and sweeping waterfront vistas; an opportunity for active uses and peaceful solitude; a resource with extensive acreage for multiple uses; and a shoreline that showcases environmental stewardship. Located at the edge of a dense urban center, Potomac Park should be an easily accessible place that provides opportunities for water-oriented recreation, commemoration, and celebration in a setting that preserves the scenic landscape. The park offers great potential to relieve pressure on the historic and fragile open space of the National Mall, a vulnerable resource that is increasingly overburdened with demands for large public gatherings, active sport fields, everyday recreation, and new memorials. Potomac Park and its shoreline should offer a range of activities for the enjoyment of all. Some areas should accommodate festivals, concerts, and competitive recreational activities, while other areas should be quiet and pastoral to support picnics under a tree, paddling on the river, and other leisure pastimes. The park should be connected with the region and with local neighborhoods. MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN 47 ENHANCE THE WATERFRONT EXPERIENCE POTOMAC PARK Context Potomac Park is a relatively recent addition to Ohio Drive parallels the walkway, provides vehicular Washington. In the early years of the city it was an access, and is used by bicyclists, runners, and skaters. area of tidal marshes. As upstream forests were cut The northern portion of the island includes 25 acres and agricultural activity increased, the Potomac occupied by the National Park Service’s regional River deposited greater amounts of silt around the headquarters, a park maintenance yard, offices for the developing city. -

A Flow-Simulation Model of the Tidal Potomac River

A Flow-Simulation Model of the Tidal Potomac River A Water-Quality Study of the Tidal Potomac River and Estuary United States Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 2234-D Chapter D A Flow-Simulation Model of the Tidal Potomac River By RAYMOND W. SCHAFFRANEK U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 2234 A WATER-QUALITY STUDY OF THE TIDAL POTOMAC RIVER AND ESTUARY DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL MODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1987 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Schaffranek, Raymond W. A flow-simulation model of the tidal Potomac River. (A water-quality study of the tidal Potomac River and Estuary) (U.S. Geological Survey water-supply paper; 2234) Bibliography; p. 24. Supt. of Docs, no.: I. 19.13:2234-0 1. Streamflow Potomac River Data processing. 2. Streamflow Potomac River Mathematical models. I. Title. II. Series. III. Series: U.S. Geological Survey water-supply paper; 2234. GB1207.S33 1987 551.48'3'09752 85-600354 Any use of trade names and trademarks in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. FOREWORD a rational and well-documented general approach for the study of tidal rivers and estuaries. This interdisciplinary effort emphasized studies of the Tidal rivers and estuaries are very important features transport of the major nutrient species and of suspended of the Coastal Zone because of their immense biological sediment. -

C:\Program Files\Adobe\Acrobat 4.0\Acrobat\Plug Ins\Openall

Water Supply Demands and Resources Analysis in the Potomac River Basin Prepared for The Maryland Department of the Environment by Roland C. Steiner, Erik R. Hagen, and Jan Ducnuigeen Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 6110 Executive Boulevard, Suite 300 Rockville, Maryland 20852 November, 2000 Report No. 00 - 5 I. Executive Summary A. Introduction The objectives of the study include an assessment of current and future water demands (with a focus on consumptive use) to the year 2030, and an estimate of available resources in the non- tidal portion of the Potomac River basin. The Potomac River basin upstream of, and including the Washington metropolitan area is defined as the non-tidal portion. The assessment of future water use in this study will assist the regulatory agencies and water utilities in addressing the future adequacy of fresh water resources in the Potomac River basin. Consumptive use upstream in the Potomac River basin reduces the amount of water allocatable and available for further use by those downstream. The concept of consumptive use as used here is consistent with that of others in the field, including the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS): “That part of water withdrawn that is evaporated, transpired, incorporated into products or crops, consumed by humans or livestock, or otherwise removed from the immediate water environment,” (USGS, 1998). This is not a study that examines the environmental effects of low flow on the flora and fauna of the Potomac River, nor does this study attempt to evaluate future sources of water supply in the basin. This study does not identify potential instances where withdrawals may be greater than flow at the local scale, i.e., in particular tributaries in the headwaters of the Potomac River basin; but instead compares consumptive demand to Potomac River flows at a broader spatial scale. -

Bus Service From

Bus Service from West Arlington Cemetery Braddock Rd Potomac Park TIDAL BASIN 395 Ballston-MU POTOMAC RIVER George Washington Pkwy 10B WILSON BLVD BUS SERVICE AND BOARDING LOCATIONS BALLSTON Arlington The table shows approximate minutes between buses; check schedules for full details National schematic map Jefferson Davis Hwy N GLEBE RD Cemetery MONDAY TO FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY LEGEND not to scale BOARD AT RANDOLPH ST RANDOLPH WASHINGTON ROUTE DESTINATION BUS BAY AM RUSH MIDDAY PM RUSH EVENING DAY EVENING DAY EVENING Rail Lines Metrobus Routes East METROWAY POTOMAC YARD LINE 14th St Memorial Bridge 10A Metrobus Major Route Potomac Park Washington Blvd Metrorail Frequent, seven-day service on the core MWY Pentagon City 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 route. On branches, service levels vary. 10B m Station and Line B MWY Metroway Line ALEXANDRIA-PENTAGON LINE Frequent, seven-day BRT service Pentagon Metrorail between Braddock Rd and Crystal City Arlington Blvd 2ND ST S Under Construction 3 4 10A Pentagon m 30 30 30 30-60 60 60 60 60 10A A Arlington George Mason Dr Hall 10A Huntington m 30 30 30 30-60 60 60 60 60 S Glebe Rd Commuter D Rail Station EADS ST HUNTING POINT-BALLSTON LINE Jefferson Hwy Davis ARMY-NAVY DR 10B Ballston-MU m 30 30 30 30-60 30 30-60 30 30-60 Map Symbols Routes Operated by A City/County Systems Columbia Pike Pentagon Transit Hub 395 10B Hunting Point 30 30 30 30-60 30 30-60 30 30-60 ARLINGTON City D Metroway Station 4 DASH Alexandria MWY St Eads JOYCE ST ST HAYES DASH–ALEXANDRIA Future Metroway Station 15TH ST 15TH ST Park -

DC Citizen Science Water Quality Monitoring Report 2 0 2 0 Table of Contents Dear Friends of the River

WAter DC Citizen Science Water Quality Monitoring Report 2 0 2 0 Table of Contents Dear Friends of the River, On behalf of Anacostia Riverkeeper, I am pleased to share with you our first Annual DC Citizen Science Volunteer Water Quality Report on Bacteria in District Waters. This report focuses on 2020 water quality results from all three District watersheds: the Anacostia River, Potomac River, and Rock Creek. The water quality data we collected is critical for understanding the health of the Anacostia River and District waters; as it serves as a gauge for safe recreation potential as well as a continuing assessment of efforts in the Methodology District of Columbia to improve the overall health of 7 our streams and waterways. As a volunteer program, we are dependent on those who offer time out of their daily schedule to work 8 Anacostia River with us and care for the water quality. With extreme gratitude, we would like to thank all our volunteers and staff for the dedication, professionalism, and enthusiasm to execute this program and to provide high quality data to the public. Additionally, support 10 Potomac River from our partner organizations was crucial to running this program, so we would like to extend an additional thanks to staff at Audubon Naturalist Society, Potomac Riverkeeper, and Rock Creek 12 Rock Creek Conservancy. We hope you find this annual report a good guide to learning more about our local DC waterways. We believe that clean water is a benefit everyone should experience, one that starts with consistent and 14 Discussion publicly available water quality data.