A Trinitarian Revisioning of the Wesleyan Doctrine of Christian Perfection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Free Methodist Church, the Wesleyan Methodist Church, the Salvation Army and the Church of the Nazarene)

A Study of Denominations 1 Corinthians 14:33 (KJV 1900) - 33 For God is not the author of confusion, but of peace, as in all churches of the saints. Holiness Churches - Introduction • In historical perspective, the Pentecostal movement was the child of the Holiness movement, which in turn was a child of Methodism. • Methodism began in the 1700s on account of the teachings of John and Charles Wesley. One of their most distinguishing beliefs was a distinction they made between ordinary and sanctified Christians. • Sanctification was thought of as a second work of grace which perfected the Christian. Also, Methodists were generally more emotional and less formal in their worship. – We believe that God calls every believer to holiness that rises out of His character. We understand it to begin in the new birth, include a second work of grace that empowers, purifies and fills each person with the Holy Spirit, and continue in a lifelong pursuit. ―Core Values, Bible Methodist Connection of Churches • By the late 1800s most Methodists had become quite secularized and they no longer emphasized their distinctive doctrines. At this time, the "Holiness movement" began. • It attempted to return the church to its historic beliefs and practices. Theologian Charles Finney was one of the leaders in this movement. When it became evident that the reformers were not going to be able to change the church, they began to form various "holiness" sects. • These sects attempted to return to true Wesleyan doctrine. Among the most important of these sects were the Nazarene church and the Salvation Army. -

John Wesley's Teaching Concerning Perfection Edward W

JOHN WESLEY'S TEACHING CONCERNING PERFECTION EDWARD W. H. VICK Andrews University, Berrien Springs, Michigan Wesley has often been characterized as Arminian rather than as Calvinistic. The fact that he continuously called for repentance from sin, published a journal called the Arminian Magazine, was severe in his strictures against predestination and unconditional election, engaged in controversial cor- respondence with Whitefield over the matter of election, perfection and perseverance seem to indicate a great gulf between his teaching and that of Calvin. Gulf there may be, but it need not be made to appear wider at certain points than can justly be claimed. The fact is that exclusive attention to his opposition to predestination may lead to neglect of his teaching on the relationship between faith and grace. This is not to deny that Wesley was opposed to important Calvinistic tenets. In his sermon on Free Grace, delivered in 1740, he states why he is opposed to the doctrine of pre- destination : (I) it makes preaching vain, needless for the elect and useless for the non-elect ; (2) it takes away motives for following after holiness ; (3) it tends to increase sharpness of temper and contempt for those considered to be outsiders ; (4) it tends to destroy the comfort of religion ; (5) it destroys zeal for good works ; (6) it makes the whole Christian revelation unnecessary and (7) self-contradictory ; (8) it represents the Lord as saying one thing and meaning J. Wesley, Sermons on Several Occasions, I (New York, 1827)~ 13-19. 202 EDWARD W. H. VICK another: God becomes more cruel and unjust than the devil. -

Becoming Lutheran: Exploring the Journey of American Evangelicals Into Confessional Lutheran Thought

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project Concordia Seminary Scholarship 9-23-2013 Becoming Lutheran: Exploring the Journey of American Evangelicals into Confessional Lutheran Thought Matthew Richard Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Richard, Matthew, "Becoming Lutheran: Exploring the Journey of American Evangelicals into Confessional Lutheran Thought" (2013). Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project. 138. https://scholar.csl.edu/dmin/138 This Major Applied Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONCORDIA SEMINARY SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURI BECOMING LUTHERAN: EXPLORING THE JOURNEY OF AMERICAN EVANGELICALS INTO CONFESSIONAL LUTHERAN THOUGHT A MAJOR APPLIED PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY STUDIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY REV. MATTHEW R. RICHARD SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURI BECOMING LUTHERAN: EXPLORING THE JOURNEY OF AMERICAN EVANGELICALS INTO CONFESSIONAL LUTHERAN THOUGHT REV. MATTHEW R. RICHARD SEPTEMBER 23, 2013 Concordia Seminary Saint Louis, Missouri Advisor DR. ROBERT -

An Unholy Trinity: the Liberal, Charismatic, and Evangelical Movements in the Lutheran Church Today by Martin R

An Unholy Trinity: The Liberal, Charismatic, and Evangelical Movements in the Lutheran Church Today by Martin R. Noland Presented to the Lutheran Bible Conference at The Lutheran Church of Our Savior, Cupertino, California, on June 30, 2001. Basis of radio show on “Issues, etc.”, February 20, 2002; rebroadcast nationally on “Issues, etc.”, March 10, 2002. I. Introduction Anniversaries are designed to be times of remembrance. This year is the silver anniversary of the departure of the Liberal faction of the Lutheran Church— Missouri Synod in 1976 to form the Association of Evangelical Lutherans Churches, i.e., the AELC. It is time for members of the LC-MS to remember that history and to ask some deep questions about its impact on us today. What was going on in the Missouri Synod in 1976? The synod was on the verge of schism in the midst of a long and bloody ecclesiastical civil war.1 In April 1976, President J. A. O. Preus of the Missouri Synod removed four district presidents from office for ordaining Seminex graduates. In December 1976, the AELC, was organized, taking with it about 250 congregations of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod.2 Eventually about 200,000 people left the Missouri Synod for the AELC,3 a little bit less than 10% of its lay membership. In his memoirs, Liberal leader John Tietjen observed that 1200 congregations were expected to leave the LC-MS, but only 250 did.4 If his calculations were correct, that means that nearly 950 LC-MS congregations and their ministers, i.e., about 16% of the total, remained in the synod organizationally but were loyal to the goals and ideals of the Seminex group, Evangelical Lutherans in Mission (ELIM), and the AELC. -

Wesleyan Spirit-Christology

Wesleyan Spirit-Christology: inspiration from the theology of Samuel Chadwick Full version of a paper presented at the Oxford Institute of Methodist Theological Studies, August 2018 by George Bailey, [email protected] Lecturer in Mission and Wesleyan Studies, Cliff College, Derbyshire, UK Presbyteral Minister in Leeds North and East Methodist Circuit, UK Introduction This paper explores the theology of Samuel Chadwick (1860-1932) and demonstrates that within it there is a Spirit Christology in a Wesleyan framework. Spirit Christology has been the subject of theological investigation in recent decades, with proposals being made for ways to add to or adapt the more dominant Logos Christologies of the Western theological tradition so that the work of the Holy Spirit in Jesus in the Gospels, and in the experience of Christians, can be better accounted for.1 Chadwick’s theology is brought into debate with this more recent conversation, and is found to be in many ways in line with the Spirit Christology being proposed. This is not an aspect of Chadwick’s theology that has been given attention previously and new suggestions are made as to his place in the tradition of Wesleyan theology. In the process, Chadwick’s sources are considered, including the ways that he draws on a Wesleyan theology of perfection, mid to late nineteenth century language of Pentecost and baptism of the Spirit, early twentieth century liberal Protestant theological work, and his potential relationship with the seventeenth century puritan, John Owen. Most academic interest in Chadwick to date has focused on more practical issues. However, although Chadwick was primarily concerned with holiness and evangelism, it was only by the work of Holy Spirit that he experienced these being effective in his life and the life of churches, and consequently the Holy Spirit constituted the main content of his teaching to prepare people for evangelism. -

Theological Contributions of John Wesley to the Doctrine of Perfection

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 51, No. 2, 301-310. Copyright © 2013 Andrews University Press. THEOLOGICAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF JOHN WESLEY TO THE DOCTRINE OF PERFECTION THEODORE LEVTEROV Loma Linda University Loma Linda, California Introduction The doctrine of perfection is biblically based. In Matt 5:48 (NIV), Jesus declares, “Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.” However, the meaning of the term “perfection” is contested, with many different interpretations ranging from one extreme to another.1 At one end of the spectrum, it has been concluded that perfection and Christian growth is not possible, while at the other it is thought that humans can attain a state of sinless perfection. Within this range of understandings, scholars agree that no one has better described the biblical doctrine of perfection than John Wesley. For example, Rob Staples proposes that this doctrine “represents the goal of Wesley’s entire religious quest.”2 Albert Outler notes that “the chief interest and signifi cance of Wesley as a theologian lie in the integrity and vitality of his doctrine as a whole. Within that whole, the most distinctive single element was the notion of ‘Christian perfection.’”3 Harald Lindstrom indicates that “the importance of the idea of perfection to Wesley is indicated by his frequent mention of it: in his sermons and other writings, in his journals and letters, and in the hymn books he published with his brother Charles.”4 John Wesley himself affi rmed that “this doctrine is the grand depositum which God has lodged with the people called Methodists; and for the sake of propagating this chiefl y He appeared to have raised us up.”5 This article will examine Wesley’s basic contributions to the doctrine of perfection. -

Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20Th and 21St Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto ASPECTS OF ARMINIAN SOTERIOLOGY IN METHODIST-LUTHERAN ECUMENICAL DIALOGUES IN 20TH AND 21ST CENTURY Mikko Satama Master’s Thesis University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology Department of Systematic Theology Ecumenical Studies 18th January 2009 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO − HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto − Fakultet/Sektion Laitos − Institution Teologinen tiedekunta Systemaattisen teologian laitos Tekijä − Författare Mikko Satama Työn nimi − Arbetets title Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20th and 21st Century Oppiaine − Läroämne Ekumeniikka Työn laji − Arbetets art Aika − Datum Sivumäärä − Sidoantal Pro Gradu -tutkielma 18.1.2009 94 Tiivistelmä − Referat The aim of this thesis is to analyse the key ecumenical dialogues between Methodists and Lutherans from the perspective of Arminian soteriology and Methodist theology in general. The primary research question is defined as: “To what extent do the dialogues under analysis relate to Arminian soteriology?” By seeking an answer to this question, new knowledge is sought on the current soteriological position of the Methodist-Lutheran dialogues, the contemporary Methodist theology and the commonalities between the Lutheran and Arminian understanding of soteriology. This way the soteriological picture of the Methodist-Lutheran discussions is clarified. The dialogues under analysis were selected on the basis of versatility. Firstly, the sole world organisation level dialogue was chosen: The Church – Community of Grace. Additionally, the document World Methodist Council and the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification is analysed as a supporting document. Secondly, a document concerning the discussions between two main-line churches in the United States of America was selected: Confessing Our Faith Together. -

The Altar Call Method of Evangelism

THE REFORMED FAITH AND THE ALTAR CALL METHOD OF EVANGELISM The purpose of this tract can be briefly stated: it is to examine the altar-call method in the light of the Biblical system of truth. We say ʻBiblical system of truthʼ be cause it is our conviction that his is what Calvinism really is. “If anyone should ask me what I mean by a Calvinist,” wrote Charles H. Spurgeon over a century ago, “I should reply, ʻHe is one who says, Salvation is of the Lord.ʼ I cannot find in Scripture any other doctrine than this. This is the essence of the Bible. ʻHe only is my rock and my salvation.ʼ Tell me anything contrary to this truth, and it will be heresy; tell me a heresy, and I shall find its essence here— that it was departed from this great, this fundamental, this rock-like truth: ʻGod is my rock and my salvation.ʼ” Anyone who understands the true genius of Calvinism will therefore realize that there is nothing against which it “sets its face with more firmness than every form and degree of auto-soterism.” The simple assertion that man—sinful and fallen man—can do at least some thing to save him self, or to help save himself, or at least prepare himself to be saved, is utterly anathema to the Calvinist. And here in lies the reason for a careful evaluation of the modern altar-call method of evangelism. For, as Spurgeon again has ex pressed it, “ʻ…since we are nothing with out the Holy Spirit, we must avoid in our work any thing which is not of Him. -

“Altar-Call Evangelism”

“Altar-Call Evangelism” Pastor Kurt M. Smith Altar-Call Evangelism: Is it biblical? “What mean these dispatches from the battle-field? ‘Last night, fourteen souls were under conviction, fifteen were justified, and eight received full sanctification.’ I am weary of this public bragging, this counting of unhatched chickens, this exhibition of doubtful spoils. Lay aside such numberings of the people, such idle pretense of certifying in half a minute that which will need the testing of a lifetime.” This lamentation combined with sage counsel was given over a hundred years ago by Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892). It was communicated in a public lecture to his ministerial students and then published in his classic book, The Soul Winner. Spurgeon’s grief was over a style of evangelism that was all the rage in his day because of how quickly so-called results could be counted, secured and then reported publicly as a mighty “gospel” success. We know this kind of evangelism today as “altar-call” evangelism. During Spurgeon’s generation this type of evangelism was very novel, but in our day (a hundred plus years later) – it’s the norm. “But not only is it an accepted practice for churches in the 21st century, it is revered as the only sure and sacred means of acquiring conversions to Christ. Or, as one church-goer put it to me several years ago: “Without the altar-call no one will be saved.” In fact, along this same line of thinking, there is even a local pastor I know, who recently said: “Without the altar-call no church will grow in the South Georgia.” For me personally, over the past fourteen years, I have greatly questioned the legitimacy and even integrity of altar-call evangelism. -

JOHN WESLEY's CHRISTOLOGY in RECENT LITERATURE by Richard M

JOHN WESLEY'S CHRISTOLOGY IN RECENT LITERATURE by Richard M. Riss There have been a variety of interpretations of John Wesley's Chris- tology, some claiming that Wesley was well within the boundaries of orthodoxy as defined by the Council of Chalcedon (A.D. 451), others say ing that he moved in the direction of monophysitism, and yet others indi cating that he may actually have come close to advocating a form of docetism.1 This spectrum of perspectives seems broad enough to be con sistent with William J. Abraham's observation that "there are as many Wesleys as there are Wesley scholars."2 Nevertheless, it will be assumed here that it should be possible to determine Wesley's own view on this important theological matter. The following review of some of the relevant literature is in chrono logical order and will concern itself primarily with interpretations of Wes ley's Christology by Robin Scroggs (1960), William Ragsdale Cannon (1974), Charles R. Wilson (1983), Albert C. Outler (1984), John Deschner (1960, 1985, 1988), Kenneth J. Collins (1993, 2007), Randy L. Maddox (1994), Thomas C. Oden (1994), Timothy L. Boyd (2004), and Matthew Hambrick and Michael Lodahl (2007). There will also be an attempt to assess this literature in light of some of Wesley's own writings. according to docetism, Jesus was not a real man, but only appeared to be. He thus only appeared to have a body. See Randy Maddox, Responsible Grace (Nashville, Tenn.: Kingswood Books), 311, note 128. 2William J. Abraham, "The End of Wesleyan Theology," Wesley an Theolog- icalJournal 40 (spring 2005): 13. -

Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Trends and Issues in Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements" (2009). Trends and Issues in Missions. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trends and Issues in Missions by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pentecostal/Charismatic Movements Page 1 Pentecostal Movement The first two hundred years (100-300 AD) The emphasis on the spiritual gifts was evident in the false movements of Gnosticism and in Montanism. The result of this false emphasis caused the Church to react critically against any who would seek to use the gifts. These groups emphasized the gift of prophecy, however, there is no documentation of any speaking in tongues. Montanus said that “after me there would be no more prophecy, but rather the end of the world” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol II, p. 418). Since his prophecy was not fulfilled, it is obvious that he was a false prophet (Deut . 18:20-22). Because of his stress on new revelations delivered through the medium of unknown utterances or tongues, he said that he was the Comforter, the title of the Holy Spirit (Eusebius, V, XIV). -

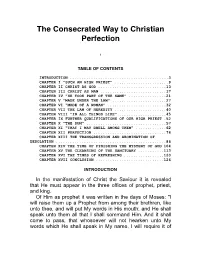

The Consecrated Way to Christian Perfection

The Consecrated Way to Christian Perfection 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..........................................3 CHAPTER I "SUCH AN HIGH PRIEST" .......................9 CHAPTER II CHRIST AS GOD .............................13 CHAPTER III CHRIST AS MAN ............................17 CHAPTER IV "HE TOOK PART OF THE SAME" ................21 CHAPTER V "MADE UNDER THE LAW" .......................27 CHAPTER VI "MADE OF A WOMAN" .........................32 CHAPTER VII THE LAW OF HEREDITY ......................40 CHAPTER VIII "IN ALL THINGS LIKE" ....................45 CHAPTER IX FURTHER QUALIFICATIONS OF OUR HIGH PRIEST .52 CHAPTER X "THE SUM" ..................................57 CHAPTER XI "THAT I MAY DWELL AMONG THEM" .............62 CHAPTER XII PERFECTION ...............................76 CHAPTER XIII THE TRANSGRESSION AND ABOMINATION OF DESOLATION ...............................................86 CHAPTER XIV THE TIME OF FINISHING THE MYSTERY OF GOD 104 CHAPTER XV THE CLEANSING OF THE SANCTUARY ...........113 CHAPTER XVI THE TIMES OF REFRESHING .................120 CHAPTER XVII CONCLUSION .............................126 INTRODUCTION In the manifestation of Christ the Saviour it is revealed that He must appear in the three offices of prophet, priest, and king. Of Him as prophet it was written in the days of Moses: "I will raise them up a Prophet from among their brethren, like unto thee, and will put My words in His mouth; and He shall speak unto them all that I shall command Him. And it shall come to pass, that whosoever will not hearken unto My words which He shall speak in My name, I will require it of him." Deut. 18:18,19. And this thought was continued in the succeeding scriptures until His coming. Of Him as priest it was written in the days of David: "Yet have I set ['anointed,' margin] My King upon My holy hill of Zion." Ps.