256 Proceedings of the Royal Society to Take a Particular Example, Let V = 1000 Feet a Second, and Let P = the Density of Water, So That

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decision Notice

[email protected] Inch Cape Offshore Limited 5th Floor, 40 Princes Street Edinburgh EH2 2BY Our Reference: 048/OW/RRP-10 17 June 2019 Dear THE ELECTRICITY ACT 1989 (AS AMENDED) THE ELECTRICITY WORKS (ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT) (SCOTLAND) REGULATIONS 2017 (AS AMENDED) DECISION NOTICE FOR THE SECTION 36 CONSENT FOR THE CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATION OF THE INCH CAPE OFFSHORE WIND FARM, APPROXIMATELY 15-22KM EAST OFF THE ANGUS COASTLINE DECLARATION UNDER SECTION 36A OF THE ELECTRICITY ACT 1989 (AS AMENDED) TO EXTINGUISH PUBLIC RIGHTS OF NAVIGATION SO FAR AS THEY PASS THROUGH THOSE PLACES WITHIN THE TERRITORIAL SEA WHERE STRUCTURES FORMING PART OF THE INCH CAPE OFFSHORE WIND FARM GENERATING STATION ARE TO BE LOCATED 1 Application and Description of the Development On 15 August 2018, Inch Cape Offshore Limited (Company Number SC373173) having its registered office at 5th Floor, 40 Princes Street, Edinburgh EH2 2BY (“ICOL” or “the Company”), submitted to the Scottish Ministers applications under the Electricity Act 1989 (as amended) (“the Electricity Act 1989”) for: A consent under section 36 (“s.36”) of the Electricity Act 1989 for the construction and operation of the Inch Cape Offshore Wind Farm, approximately 15-22km east off the Angus coastline; and 1 A declaration under section 36A (“s.36A”) of the Electricity Act 1989 to extinguish public rights of navigation so far as they pass through those places within the Scottish marine area (essentially the territorial sea adjacent to Scotland) where structures forming part of the Inch Cape Offshore Wind Farm are to be located. These applications are collectively referred to as “the Application”. -

SE Enterprise & Lifelong Learning Department

Contents 1. Introduction 2. Aim of this Scoping Opinion 3. Description of your development Onshore elements Offshore elements 4 Relevant Legislation & Planning Policies Marine Scotland & Licensing National & Scottish Planning Policies Local Authority Guidance Strategic Environmental Assessment 5. Natural Heritage 6. General Issues Economic Benefit 7. Contents of the Environmental Statement (ES) Format Non Technical Summary Site selection and alternatives Description of the Development Decommissioning Grid Connection Details 8. Baseline Assessment and Mitigation Air, Climate and Carbon Emissions Design, Landscape and the Built Environment Construction Mammals and Seabirds Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Navigation Aviation 9. Ecology, Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Designated sites Habitats Species 1 abcde abc a Birds Mammals Reptiles and amphibians Fish Invertebrates Sub-Tidal Benthic Ecology 10. Water Environment Hydrology and Hydrogeology 11. Other Material Issues Waste Noise Traffic Management 12. General ES Issues Consultation Gaelic Language OS Mapping Records Difficulties in Compiling Additional Information Application and Environmental Statement Consent Timescale and Application Quality Judicial Review 2 abcde abc a THE ELECTRICITY WORKS (ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT) (SCOTLAND) REGULATIONS 2000. SCOPING OPINION FOR THE PROPOSED SECTION 36 APPLICATION FOR NEART NA GAOITHE OFFSHORE WIND FARM 1. Introduction I refer to your letter of 9 November 2009 requesting a scoping opinion under the Electricity Works (Environmental Impact Assessment)(Scotland)(EIA) Regulations 2000 and Regulation 13 of the Marine Works (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2007 enclosing a scoping report dated November 2009. Any proposal to construct or operate an offshore power generation scheme with a capacity in excess of 1 megawatt requires Scottish Ministers’ consent under section 36 of the Electricity Act 1989. -

Discover North Berwick

Heritage Lottery Fund. Fund. Lottery Heritage Scottish Natural Heritage and the the and Heritage Natural Scottish East Lothian’s iconic hill hill iconic Lothian’s East guide. Funding was provided by by provided was Funding guide. A 1 mile walk up up walk mile 1 A and advice in the production of this this of production the in advice and Countryside Ranger, for her support support her for Ranger, Countryside North Berwick Law Law Berwick North like to thank Sam Ranscombe, Ranscombe, Sam thank to like The wild plants of of plants wild The East Lothian Council. We would would We Council. Lothian East North Berwick. North North Berwick Law is managed by by managed is Law Berwick North There are public toilets in in toilets public are There Thank you Thank WC Cover photo: ©Graeme Maclean ©Graeme photo: Cover May 2013 May cafés and restaurants. and cafés 978-1-907141-83-6 ISBN: ISBN: drink in North Berwick at its many its at Berwick North in drink Tel: 01722 342730 01722 Tel: Salisbury, Wiltshire, SP1 1DX, UK 1DX, SP1 Wiltshire, Salisbury, There are many options for food and food for options many are There Plantlife, 14 Rollestone Street, Street, Rollestone 14 Plantlife, Refreshments Registered in Scotland, Charity no. SCO38951. no. Charity Scotland, in Registered Company No. 3166339. Registered in England and Wales, Charity No. 1059559. 1059559. No. Charity Wales, and England in Registered 3166339. No. Company e is a charitable company limited by guarantee, guarantee, by limited company charitable a is e Plantlif sections. uneven and slippery rocky, some includes life.org.uk www.plant A short, but steep and strenuous walk. -

Download This PDF: Living East Lothian

PAGE 2 PAGES 8 & 9 It’s a deal! Are you ready for winter? £1.3bn investment will boost Handy guide on how you can the economy in city region stay safe in severe weather PAGE 5 PAGE 13 Building HOW SAFE IS communities YOUR MONEY? We’re delivering affordable housing Campaign to where it’s needed most prevent financial scams www.eastlothian.gov.uk WINTER 2018 NEWS FROM YOUR COUNCIL Watch out Jack, your mum’s dressed to impress! Queen Margaret University students have helped make the costumes for panto Dame, Mither Mandy Moo Moo, starring in Jack and the Beanstalk at The Brunton. Read the full story on page 16. Groundworks under way for new town REPARATORY First step in council’s ambitious plan to create exciting economically – to their groundworks are taking surroundings and which promote place on a large area of new community fit for the 21st century and beyond healthy lifestyles, wellbeing and land at the former physical activity. I believe this can PBlindwells site, where the It is also one of seven major improvements to roads. “It means we need to need to be achieved sustainably and council has plans to create a sites considered to be Councillor Norman Hampshire, think now and plan to deliver the using new, innovative approaches. vibrant new East Lothian strategically significant within Cabinet Spokesperson for the community we ultimately want “There is a lot of work to do and community for the 21st century the Edinburgh and South East Environment, said: “Many people to see – one that helps us to it requires ambitious, quality and beyond. -

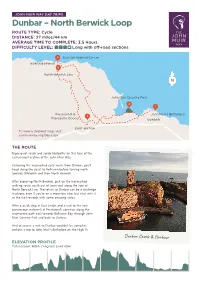

North Berwick Loop ROUTE TYPE: Cycle DISTANCE: 27 Miles/44 Km AVERAGE TIME to COMPLETE: 3.5 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Long with Off-Road Sections

JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Dunbar – North Berwick Loop ROUTE TYPE: Cycle DISTANCE: 27 miles/44 km AVERAGE TIME TO COMPLETE: 3.5 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Long with off-road sections 4 Scottish Seabird Centre NORTH BERWICK 5 North Berwick Law John Muir Country Park 2 1 Prestonmill & John Muir’s Birthplace 3 Phantassie Doocot DUNBAR EAST LINTON To view a detailed map, visit joinmuirway.org/day-trips THE ROUTE Enjoy quiet roads and sandy footpaths on this tour of the easternmost section of the John Muir Way. Following the waymarked cycle route from Dunbar, you’ll head along the coast to Belhaven before turning north towards Whitekirk and then North Berwick. After exploring North Berwick, pick up the waymarked walking route south out of town and along the foot of North Berwick Law. The return to Dunbar can be a challenge in places, even if you’re on a mountain bike, but stick with it as the trail rewards with some amazing vistas. After a quick stop in East Linton and a visit to the very picturesque watermill at Prestonmill, continue along the waymarked path east towards Belhaven Bay, through John Muir Country Park and back to Dunbar. And of course a visit to Dunbar wouldn’t be complete without a trip to John Muir’s Birthplace on the High St. Dunbar Castle & Harbour ELEVATION PROFILE Total ascent 369m / Highest point 69m JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Dunbar - North Berwick Loop PLACES OF INTEREST 1 JOHN MUIR’S BIRTHPLACE Pioneering conservationist, writer, explorer, botanist, geologist and inventor. Discover the many sides to John Muir in this museum located in the house where he grew up. -

Best Boot Forward

Best boot forward Newsletter for East Lothian Countryside Volunteers July 2018 No room for a waffling introduction this month, thanks to a jam-packed issue! Thanks to everyone who has contributed. Look forward to seeing lots of you at the Volly Jolly on 1st September (let Duncan know if you are coming) and let me know if you would like to come along on the museum bug trip on 11th Sept – it should be an interesting visit. Conservation Volunteer tasks scheduled this month: New faces always welcome! If you would like to join in with a group for the first time, please get in touch with the relevant ranger to confirm details. Also see: www.elcv.org.uk/dates/ Yellowcraig Dave; [email protected] Aberlady John; [email protected] North Berwick Sam; [email protected] Path Warden team task Duncan [email protected] Dunbar CVs Tara/Laura; [email protected] Ranger-led Activities and Hikes Visit www.eastlothian.gov.uk/rangerevents for details and to book. Also remember the Rangers are leading a number of day trips around the county (by minibus and by bike!). Please pass on to friends and family who might be interested. Our Ranger team are fun to be with and know lots of things so they should be a great way to get to explore some of East Lothian’s wildlife and wild places HIKE: Over the Hills and Far Away: Sunday 19th August 10:00 An 11-mile hill walk along established tracks and trails through the Lammermuir Hills from Lammer Law to Faseny. -

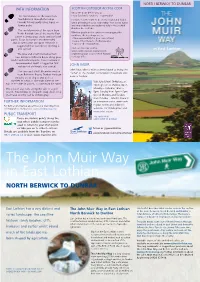

The John Muir Way in East Lothian North Berwick to Dunbar

NORTH BERWICK TO DUNBAR PATH INFORMATION SCOTTISH OUTDOOR ACCess CODE Know the Code before you go … The first kilometre of the route from Enjoy Scotland’s outdoors – responsibly! North Berwick through the Lodge Everyone has the right to be on most land and inland Grounds follows gently rising slopes on water providing they act responsibly. Your access rights tarmac paths. and responsibilities are explained fully in the Scottish Outdoor Access Code. The ten kilometres of the route from North Berwick Law all the way to East Whether you’re in the outdoors or managing the Linton is along grass tracks and surfaced outdoors, the key things are to: • take responsibility for your own actions; paths. Stout footwear is recommended • respect the interests of other people; and as some areas are quite remote it is • care for the environment. suggested that waterproof clothing is also carried. Find out more by visiting: in East Lothian www.outdooraccess-scotland.com The nine and a half kilometres from or phoning your local Scottish Natural East Linton to Belhaven Bay is along grass Heritage office. tracks and surfaced paths. Stout footwear is recommended and it is suggested that waterproof clothing is also carried. JOHN MUIR John Muir, who is often acknowledged as being the The two and a half kilometre section ‘father’ of the modern conservation movement was from Belhaven Bay to Dunbar Harbour born in Dunbar. includes steep slopes and quite a number of steps. It also runs close to the Visit John Muir’s Birthplace at top of the cliffs in places, so care must be taken. -

East Lothian Life Index

East Lothian Life Index A A1 Road Dualling Tranent to Haddington 21, 18; Haddington to Dunbar 42, 16; 43, 28 A Future for the Past (Property) 27 A Meadow in Haddington (Property) 22 A Seasonal relection on beekeeping 92,37 Aberdeen Asset Management Scottish Open 92,41 Abbey Mill 34, 16; 45, 34 Aberlady 13, 13; 59, 45 Aberlady Angles 98, 72 Bay 8, 20; 35, 20 Bowling Club 84, 30 Cave 57, 30 Climate Friendly 105, 19 Curling Club 1860-2010 75, 53 Scale Model Project 57, 39 Submarines 60, 22 Village 59, 45: 60, 39 Village Kirk (The) 70, 40 Acorn Designs 10, 15 Act of Union 27, 9 Act Now to cut your Heating Costs (Property) 31 Acute Oak Decline 97,27 Adam, Robert 41, 34 Adventure Driving 1, 16 After the great War – peace in Musselburgh 73, 49 After the great War 2 75, 49 After the pips 70, 16 Aikengall 53, 28 Airfields 6, 25; 60, 33 Airships 45, 36 Alba Trees 9, 23 Alder, Ruth 50, 49 Alderston House (Homes) 29, 6 Alexander, Dr Thomas 47, 45 Allison Cargill House (Homes) 38, 40 Allotted time (Gardening) 63, 15 Allure of Haddington etc (Property), The 41 Alpacas 54, 30 Amisfield 16, 14 Amisfield Murder 60, 24 Amisfield Secret Garden 32, 10 Amisfield Lost Pineapple House 84, 27 Amisfield Park 91, 18 A night to remember – Haddington’s Blitz 78, 51 An East Lothian Icon – the Lewis Organ 80, 40 Ancient Settlements – Auldhame 97, 34 Anderson Strathearn – Graham White 99, 14 Anderson, William 22, 31 An East Lothian Gangabout 74, 30, 76, 28, 77, 28 An East Lothian Walkabout with Patrick Neill 1776-1851 75, 30 Angus, George 26, 16 Antiques Action at an -

Countryside Annual Report 2017-18

EAST LOTHIAN COUNTRYSIDE SERVICE Annual Report 2017/18 47km coast managed WELCOME FOREWORD >2.5million “I am delighted to present Countryside Service’s Annual Report for 2017 – 18. seaside awards visitors welcomed to our sites This report captures and highlights both the range and depth of work completed by East Lothian Council’s 7 Countryside Service within the past financial year.” 348km £229,000+ grants/income secured of d c ne ore tai Eamon John paths main Manager Sport, Countryside & Leisure protected species 9,322 conserved volunteer hours given 31 countryside sites looked after Feedback on how you find the report, how easy it is to follow and depth of information should be directed 168 to; [email protected] schools 118 other groups/events ANNUAL REPORT 2017-2018 | 1 CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY 4 2. THE COUNTRYSIDE SERVICE - WHO WE ARE 4 3. WHERE WE OPERATE 6 4. WHY WE DO IT 7 5. WHAT WE DO 8 6. WEATHER SUMMARY 9 7. WHAT WE DID 10 1. OUTDOOR ACCESS 10 2. BIODIVERSITY 14 3. EAST LOTHIAN COUNTRYSIDE RANGER SERVICE 16 4. OTHER COUNTRYSIDE PROJECT WORK 20 5. EXPENDITURE 24 8. APPENDICES 25 1. THE COUNTRYSIDE ESTATE 25 2. ADVISORY GROUPS 26 3. PHOTOGRAPHS 31 2 | EAST LOTHIAN COUNTRYSIDE SERVICE ANNUAL REPORT 2017-2018 | 3 1. SUMMARY 2.2 STRUCTURE The Countryside Service exists to protect East authority networks of core paths providing Eamon John Lothian’s biodiversity and promote sustainable active travel alternatives as well as health and Manager; Sport, Countryside & Leisure management, responsible use, access and recreation opportunities. -

Scottish Natural Heritage Explore for a Day East Lothian

Scottish Natural Heritage Explore for a day East Lothian Explore for a day East Lothian East Lothian combines the best of Scotland! The Lammermuir Symbol Key Hills to the south give way to an expanse of gently rolling rich arable farmland, bounded to the north by 40 miles of Parking Information Centre magnificent coastline. It’s only minutes from Edinburgh by car, train or bus, but feels Paths Disabled Access like a world away. Discover the area and its award winning attractions by following the suggested routes, or simply create your own perfect day. Toilets Wildlife watching Refreshments Picnic Area Admission free unless otherwise stated. 1 1 4.4 Dirleton Castle Romantic Dirleton Castle has graced the heart of the picturesque village of Dirleton since the 13th century. For the first 400 years, it served as the residence of three noble families. It was badly damaged during Cromwell’s siege of 1650, but its fortunes revived in the 1660s when the Nisbet family built a new mansion close to the ruins. The beautiful gardens that grace the castle grounds today date from the late 19th and early 20th centuries and include the world’s longest herbaceous border! Admission charge. Open Apr – Sept 9.30 – 5.30pm; Oct – Mar 9.30 – 4.30pm. Postcode: EH39 5ER Tel: 01620 850330 www.historic-scotland.gov.uk 1.1 Levenhall Links 5 The unlikely setting of a landscaped spoil heap from a power station provides a year round spectacle and an area fast becoming Scotland’s premier birdwatching site. Levenhall boasts a variety of habitats including shallow water scrapes, a boating pond, ash lagoons, hay meadow, woodland and utility grassland. -

COS 1 Bradbury York Road 2

THE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND EAGLAIS NA H-ALBA FLAT 1, BRADBURY, 2 YORK ROAD, NORTH BERWICK, EH39 4LS Offers Over £208,000 DESCRIPTION This attractive ground floor flat forms part of a detached Victorian villa conversion in the highly sought after West side of North Berwick. Located within easy walking distance of the town centre and the beach, this apartment offers superb potential to form an elegant and convenient home. LOCATION Situated on the coastline of East Lothian, North Berwick is a highly desirable seaside town with a host of amenities, within easy travelling distance of Edinburgh. The prop- erty is close to North Berwick’s fine beaches and High Street. There is a range of local shops and restaurants, and well regarded primary and secondary schools. There are lots of recreational facilities including excellent golf courses, a rugby club, tennis courts, sailing, swimming pool, sports centre and a yacht club. Many fine walks can be found in the vicinity, including that to North Berwick Law. The Scottish Seabird Centre is found on the harbour. North Berwick railway station is a short walk from the property, and runs to Edin- burgh Waverley. Local bus routes provide access to Haddington, Musselburgh, Dun- bar and Edinburgh. ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: Bright entrance hall, large lounge with bay window (12’2” x 15’5”), kitchen (7’0” x 9’6”), bedroom (19’6” x 12’7”) and bathroom (8’5” x 9’7”). Four large cupboards provide ample storage. Lower Ground Floor: Useful additional good sized room with window overlooking garden, with potential for use as a study or similar. -

Spring 2020 Free

ISSUE 57 - SPRING 2020 FREE StramashThe Orwell and Portmoak Quarterly Parish Magazine Scottish Charity Number: SC015523 HOPE AND JOY All shall be made right! LOVE IN ACTION So many reasons to be hopeful! 17th Century Scottish Castle Castle Wedding for 110 and Family Home Marquee Wedding for over 200 Grade A Listed with a 9th century [email protected] ruined medieval church, maze and a www.tullibolecastle.com 150 yard ‘moat’ situated in its parkland Tel: 01577 840236 OPENING TIMES MON 9-5 WED 9-5 THUR 9-5 FRI 9-5 SAT 9-4 101 HIGH ST. LATE NIGHT ON REQUEST KINROSS KY13 8AQ SUBJECT TO AVAILABILITY 01577 862095 FIND US ON | 39 High Street, Kinross KY13 8AA 1 on this issue, and what contrasting Dear Friends, emotions our departure has evoked. The old phrase ‘betwixt and Exuberant parties of celebration between’ has just come to in some places were matched by have a new resonance for wake-like gatherings in others. For us all in this country. A few some, this is an exciting moment hours ago (as I write) we woke up of great progress in our national to find ourselves in exactly that life; for others, there has been an situation, having now officially left the overwhelming feeling of sadness European Union. We haven’t been and loss for what’s past, and of here for nearly half a century and apprehension about what the future Life is usually more grey than black some readers at least will never have might hold. and white. We can but hope that known life except as citizens of the we will at least see an end to the EU.