April Scott Dissertation Finaldraft AUETD.Pdf (485.9Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 25, 2014

University of Mississippi eGrove Daily Mississippian Journalism and New Media, School of 9-25-2014 September 25, 2014 The Daily Mississippian Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/thedmonline Recommended Citation The Daily Mississippian, "September 25, 2014" (2014). Daily Mississippian. 922. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/thedmonline/922 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and New Media, School of at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Daily Mississippian by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thursday, September 25, 2014 THE DAILY Volume 103, No. 23 THE STUDENTMISSISSIPPIAN NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI SERVING OLE MISS AND OXFORD SINCE 1911 Visit theDMonline.com @thedm_news opinion lifestyles sports CARTOON: How much Wommack Government Mustard is too prepares for food services much? Memphis offense Page 2 Page 4 Page 6 UPD discusses action plans for campus crisis PHOTO BY: THOMAS GRANING University Police Officer Michael Hughes watches on during a traffic stop in April. KYLE WOHLEBER to react to an active shooter also a call about a suspicious have been here to help us in the “We were having meetings [email protected] on campus. UPD Chief of Po- package in the Malco Movie past. They come and assist us in here 6 o’clock Friday night,” lice Calvin Sellers said the only Theater parking lot for which with a sweep of the football sta- Sellers said. “They were having threats he’s had to respond to in UPD brought in the Tupelo dium Friday nights before the meetings at the athletic depart- With the anonymous threats his time at the department have bomb squad. -

Music 6581 Songs, 16.4 Days, 30.64 GB

Music 6581 songs, 16.4 days, 30.64 GB Name Time Album Artist Rockin' Into the Night 4:00 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Caught Up In You 4:37 .38 Special: Anthology .38 Special Hold on Loosely 4:40 Wild-Eyed Southern Boys .38 Special Voices Carry 4:21 I Love Rock & Roll (Hits Of The 80's Vol. 4) 'Til Tuesday Gossip Folks (Fatboy Slimt Radio Mix) 3:32 T686 (03-28-2003) (Elliott, Missy) Pimp 4:13 Urban 15 (Fifty Cent) Life Goes On 4:32 (w/out) 2 PAC Bye Bye Bye 3:20 No Strings Attached *NSYNC You Tell Me Your Dreams 1:54 Golden American Waltzes The 1,000 Strings Do For Love 4:41 2 PAC Changes 4:31 2 PAC How Do You Want It 4:00 2 PAC Still Ballin 2:51 Urban 14 2 Pac California Love (Long Version 6:29 2 Pac California Love 4:03 Pop, Rock & Rap 1 2 Pac & Dr Dre Pac's Life *PO Clean Edit* 3:38 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2006 2Pac F. T.I. & Ashanti When I'm Gone 4:20 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3:58 Away from the Sun 3 Doors Down Bailen (Reggaeton) 3:41 Tropical Latin September 2002 3-2 Get Funky No More 3:48 Top 40 v. 24 3LW Feelin' You 3:35 Promo Only Rhythm Radio July 2006 3LW f./Jermaine Dupri El Baile Melao (Fast Cumbia) 3:23 Promo Only - Tropical Latin - December … 4 En 1 Until You Loved Me (Valentin Remix) 3:56 Promo Only: Rhythm Radio - 2005/06 4 Strings Until You Love Me 3:08 Rhythm Radio 2005-01 4 Strings Ain't Too Proud to Beg 2:36 M2 4 Tops Disco Inferno (Clean Version) 3:38 Disco Inferno - Single 50 Cent Window Shopper (PO Clean Edit) 3:11 Promo Only Rhythm Radio December 2005 50 Cent Window Shopper -

David Lee Murphy, Kenny Chesney Are Doing 'Alright' with Feel-Good

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE NOVEMBER 27, 2017 | PAGE 14 OF 19 MAKIN’ TRACKS TOM ROLAND [email protected] David Lee Murphy, Kenny Chesney Are Doing ‘Alright’ With Feel-Good Reminder Don’t go hitting that panic button. Creating a country song that takes place in a bar isn’t a new idea, but that David Lee Murphy, who threaded that message into the chorus of his Kenny was never a concern in the writing room because the message went way beyond Chesney collaboration “Everything’s Gonna Be Alright,” knows a little about its locale. trusting time. After notching four top 10 singles on Billboard’s Hot Country “We didn’t focus on the bar or the beach,” says Yeary. “We focused on the Songs chart in 1995 and 1996 — including the now-classic No. 1 “Dust on problem — the monkey on the back of that guy.” the Bottle” — Murphy waited eight years to return to that tier with “Loco.” That set up one of the song’s most unique images in the second verse. Most Thirteen years after that, early indications are that he’s got another hit on his situations require some wrestling to shake that monkey, but in this case, the hands as an artist with three minutes and 52 seconds of timely reassurance. sign provided just enough calm that no fight was necessary. The monkey slides “I’m getting a lot of nice notes from people throughout the industry,” says off the protagonist’s back “right into the deep blue sea.” Murphy of his return, “so it’s really cool.” “There’s probably some deep underlying psychology to that,” says Stevens. -

2018 Popular Hits **

Page 1 of 9 ** 2018 POPULAR HITS ** Name Time Album Artist 1 Ven Bailalo 4:12 Strictly Latin Dancing Come And Dance Angel Y Khriz 2 Focus (Intro) 4:05 Single - Focus Ariana Grande 3 One Last Time (Intro) 4:00 Single - One Last Time Ariana Grande 4 Lonely Together (Intro) ft. Rita Ora 3:45 Single - Lonely Together Avicii 5 Cyclone w/ T.I. (Clean) 3:44 Single - Cyclone Baby Bash 6 Poison 4:26 Valentine's Day Compilation 2004 Bell Biv Devoe 7 6 Inch (Intro - Clean) ft. The Weeknd 4:59 Single - 6 Inch Beyonce 8 Formation - KidCutUp Clap Intro (Clean) 4:27 Single - Formation Beyonce 9 Formation (Intro - Clean) 4:55 Single - Formation Beyonce 10 Single Ladies - Freejak Shape Of You Edit (Intro) 4:07 Single - Single Ladies FREEJAK MIX Beyonce 11 Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 3:13 I Am...Sasha Fierce Beyonce Knowles 12 Bounce Back (Intro - Clean) 4:25 Single - Bounce Back Big Sean 13 I Gotta Feeling (Tonight) 4:49 The E.n.d. (the Energy Never Dies) Black Eyed Peas 14 My Humps (AC/DC BEAT) REMIX 4:51 Mash-Ups Black Eyed Peas 15 Let's Get It Started REMIXED 5:12 Remix of Original Black Eyed Peas 16 The Time (Dirty Bit) (Intro - Clean) 4:38 Single - The Time (Dirty Bit) Black Eyed Peas 17 No Diggity (LP Version) 5:07 No Diggity (Single) Blackstreet 18 Gimme More RMX (Dirty Intro) w/ T.I. 4:34 Gimme More (Single) Britney Spears 19 24K Magic (Intro - Clean) 3:53 Single - 24K Magic Bruno Mars 20 Finesse Remix (Hook First - Clean) ft. -

The Snow Miser Song 6Ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (Feat

(Sandy) Alex G - Brite Boy 1910 Fruitgum Company - Indian Giver 2 Live Jews - Shake Your Tuchas 45 Grave - The Snow Miser Song 6ix Toys - Tomorrow's Children (feat. MC Kwasi) 99 Posse;Alborosie;Mama Marjas - Curre curre guagliò still running A Brief View of the Hudson - Wisconsin Window Smasher A Certain Ratio - Lucinda A Place To Bury Strangers - Straight A Tribe Called Quest - After Hours Édith Piaf - Paris Ab-Soul;Danny Brown;Jhene Aiko - Terrorist Threats (feat. Danny Brown & Jhene Aiko) Abbey Lincoln - Lonely House - Remastered Abbey Lincoln - Mr. Tambourine Man Abner Jay - Woke Up This Morning ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE - Are We Experimental? Adolescents - Democracy Adrian Sherwood - No Dog Jazz Afro Latin Vintage Orchestra - Ayodegi Afrob;Telly Tellz;Asmarina Abraha - 808 Walza Afroman - I Wish You Would Roll A New Blunt Afternoons in Stereo - Kalakuta Republik Afu-Ra - Whirlwind Thru Cities Against Me! - Transgender Dysphoria Blues Aim;Qnc - The Force Al Jarreau - Boogie Down Alabama Shakes - Joe - Live From Austin City Limits Albert King - Laundromat Blues Alberta Cross - Old Man Chicago Alex Chilton - Boplexity Alex Chilton;Ben Vaughn;Alan Vega - Fat City Alexia;Aquilani A. - Uh La La La AlgoRythmik - Everybody Gets Funky Alice Russell - Humankind All Good Funk Alliance - In the Rain Allen Toussaint - Yes We Can Can Alvin Cash;The Registers - Doin' the Ali Shuffle Amadou & Mariam - Mon amour, ma chérie Ananda Shankar - Jumpin' Jack Flash Andrew Gold - Thank You For Being A Friend Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness - Brooklyn, You're -

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In Love Beyonce BoomBoom Pow Black Eyed Peas Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Old Time Rock n Roll Bob Seger Forever Chris Brown All I do is win DJ Keo Im shipping up to Boston Dropkick Murphy Now that we found love Heavy D and the Boyz Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande and Nicki Manaj Let's get loud J Lo Celebration Kool and the gang Turn Down For What Lil Jon I'm Sexy & I Know It LMFAO Party rock anthem LMFAO Sugar Maroon 5 Animals Martin Garrix Stolen Dance Micky Chance Say Hey (I Love You) Michael Franti and Spearhead Lean On Major Lazer & DJ Snake This will be (an everlasting love) Natalie Cole OMI Cheerleader (Felix Jaehn Remix) Usher OMG Good Life One Republic Tonight is the night OUTASIGHT Don't Stop The Party Pitbull & TJR Time of Our Lives Pitbull and Ne-Yo Get The Party Started Pink Never Gonna give you up Rick Astley Watch Me Silento We Are Family Sister Sledge Bring Em Out T.I. I gotta feeling The Black Eyed Peas Glad you Came The Wanted Beautiful day U2 Viva la vida Coldplay Friends in low places Garth Brooks One more time Daft Punk We found Love Rihanna Where have you been Rihanna Let's go Calvin Harris ft Ne-yo Shut Up And Dance Walk The Moon Blame Calvin Harris Feat John Newman Rather Be Clean Bandit Feat Jess Glynne All About That Bass Megan Trainor Dear Future Husband Megan Trainor Happy Pharrel Williams Can't Feel My Face The Weeknd Work Rihanna My House Flo-Rida Adventure Of A Lifetime Coldplay Cake By The Ocean DNCE Real Love Clean Bandit & Jess Glynne Be Right There Diplo & Sleepy Tom Where Are You Now Justin Bieber & Jack Ü Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun Renegades X Ambassadors Hotline Bling Drake Summer Calvin Harris Feel So Close Calvin Harris Love Never Felt So Good Michael Jackson & Justin Timberlake Counting Stars One Republic Can’t Hold Us Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Ft. -

13 Biibd: Music HOTR&Bfrfipap , YTM

DECEMBER 13 BiIbd: Music HOTR&BfrFIPAP , YTM u w W w + TITLE = TITLE S _ TITLE Temptations, the Whispers and r g ARTIST (IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL) F , ARTIST (IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL) 1- g ARTIST (IMPRINT /PROMOTION LABEL) Y- NUMBER 1 Lakeside will be among the hon- 1 y2 1 Step In The Name Of Love wuallo.I 26 21 Clap Back ® 55 Quick To Back Down Rhythm R. KELLY IJIVEI ", JA RULE (MURDER INCJDEFJAM/IOJMG) orees at the second annual Black BRAVEHEARTS(ILL WIWCOLUMBINSUMI Q 5 You Don't Know My Name ® 41 Not Today 53 The Set Up Music Awards. The Dec. 14 ALICIA KEYS (JA1MG) MARY J. BLIGE FEAT. EVE ¡GEFFEN) OBIE TRICE FEAT. NATE DOGG ISHADY /INTERSCOPB soirée -presented by the Los 3 3 Walked Outta Heaven m 30 Gigolo 53 Touched A Dream & Blues JAGGED EDGE ICOLUMBINSUMI NICK CANNON FEAT. R. KELLY (NICK/JIVE) R. KELLY IJIVEI Angeles Black Music Assn. -will 4 4 The Way You Move 29 25 Thoia Thoing 66 Pop That Booty Conti'ued from page 32 be held at Los Angeles' Wilshire OUTKAST FEAT. SLEEPY BROWN IARISTAI R. KELLY (JIVE) MARQUES HOUSTON ITU.GJELEKTRNEEGI 5 2 Stand Up Q 39 Salt Shaker 52 Suga Suga Ebell Theater. For more details, LUDACRIS (DISTURBING THA PEACE/DEF JAM SOUTMOJMGI HING YANG TWINS ICOWPARK/IVTI BABY BASH FEAT. FRANKIE J IUNIVERSAL/UMRGI visit lablackmusicawards.com. 6 6 Damn! @ 36 Through The Wire 60 Rubber Band Man VOUNGBL000Z FEAT. UL JON (SO SO DEF/ ARISTA) KANYE WEST )ROC- A- FELLADEFJAM/IDJMGI T I. IGRAND HUSTLE/ATLANTICI (Dec. -

Production Notes

PRODUCTION NOTES “This city, this whole country, is a strip club. You’ve got people tossing the money, and people doing the dance.” – Ramona Inspired by true events, HUSTLERS is a comedy-drama that follows a crew of savvy strip club employees who band together to turn the tables on their Wall Street clients. At the start of 2007, Destiny (Constance Wu) is a young woman struggling to make ends meet, to provide for herself and her grandma. But it’s not easy: the managers, DJs, and bartenders expect a cut– one way or another – leaving Destiny with a meager payday after a long night of stripping. Her life is forever changed when she meets Ramona (Jennifer Lopez), the club’s top money earner, who’s always in control, has the clientele figured out, and really knows her way around a pole. The two women bond immediately, and Ramona gives Destiny a crash course in the various poses and pole moves like the carousel, fireman, front hook, ankle-hook, and stag. Another dancer, the irrepressible Diamond (Cardi B) provides a bawdy and revelatory class in the art of the lap dance. But Destiny’s most important lesson is that when you’re part of a broken system, you must hustle or be hustled. To that end, Ramona outlines for her the different tiers of the Wall Street clientele who freQuent the club. The two women find themselves succeeding beyond their wildest dreams, making more money than they can spend – until the September 2008 economic collapse. Wall Street stole from everyone and never suffered any consequences. -

WLIR Playlist

I believe this complete list of WLIR/WDRE songs originally appeared on this site, but the full playlist is no longer available. https://wlir.fm/ It now only has the list of “Screamers and Shrieks” of the week—these were songs voted on by listeners as the best new song of the week. I’ve included the chronological list of Screamers and Shrieks after the full alphabetical playlist by artist. 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Can't Ignore The Train 10,000 Maniacs Eat For Two 10,000 Maniacs Headstrong 10,000 Maniacs Hey Jack Kerouac 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Non-Live version) 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Live) 10,000 Maniacs Peace Train 10,000 Maniacs These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10,000 Maniacs What's The Matter Here 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 12 Drummers Drumming We'll Be The First Ones 2 NU This Is Ponderous 3D Nearer 4 Of Us Drag My Bad Name Down 9 Ways To Win Close To You 999 High Energy Plan 999 Homicide A Bigger Splash I Don’t Believe A Word (Innocent Bystanders) A Certain Ratio Life's A Scream A Flock Of Seagulls Heartbeat Like A Drum A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran A Flock Of Seagulls It's Not Me Talking A Flock Of Seagulls Living In Heaven A Flock Of Seagulls Never Again (The Dancer) A Flock Of Seagulls Nightmares A Flock Of Seagulls Space Age Love Song A Flock Of Seagulls Telecommunication A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls What Am I Supposed To Do A Flock Of Seagulls Who's That Girl A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing A Popular History Of Signs The Ladderjack -

Wk 2 – 2004 Jan 10 – USA Top 100

Wk 2 – 2004 Jan 10 – USA Top 100 1 1 13 HEY YA Outkast 2 2 15 THE WAY YOU MOVE Outkast 3 3 15 MILKSHAKE Kelis 4 4 9 YOU DON'T KNOW MY NAME Alicia Keys 5 5 19 STAND UP Ludacris 6 6 19 WALKED OUTTA HEAVEN Jagged Edge 7 7 21 SUGA SUGA Baby Bash 8 8 20 HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 Doors Down 9 9 6 SLOW JAMZ Slow Twista & Kanye West 10 10 9 ME MYSELF AND I Beyonce 11 11 11 IT'S MY LIFE No Doubt 12 12 21 SOMEDAY Nickelback 13 18 37 GET LOW Lil Jon & The East Side Boyz 14 13 22 BABY BOY Beyonce 15 15 23 DAMN YoungBloodZ 16 14 17 HOLIDAE IN Chingy 17 17 9 CHANGE CLOTHES Jay-Z 18 19 15 READ YOUR MIND Avant 19 16 21 STEP IN THE NAME OF LOVE R. Kelly 20 20 13 RUNNIN' 2 Pac 21 24 10 NUMB Linkin Park 22 23 17 WHITE FLAG Dido 23 21 25 WHY DON'T YOU AND I Santana & Alex Band Or Chad Kroeger 24 27 9 GIGOLO Nick Cannon 25 22 38 HEADSTRONG Trapt 26 32 6 SALT SHAKER Ying Yang Twins 27 25 11 STUNT 101 G-Unit 28 26 14 WAT DA HOOK GON BE Murphy Lee 29 30 12 THE FIRST CUT IS THE DEEPEST Sheryl Crow 30 28 24 SO FAR AWAY Staind 31 33 7 THROUGH THE WIRE Kanye West 32 29 11 PERFECT Simple Plan 33 36 7 THE VOICE WITHIN Christina Aguilera 34 31 10 THERE GOES MY LIFE Kenny Chesney 35 34 5 REMEMBER WHEN Alan Jackson 36 35 16 BRIGHT LIGHTS Matchbox 20 37 49 43 UNWELL Matchbox 20 38 38 6 GANGSTA NATION Westside Connection 39 40 6 FUCK IT Eamon 40 41 29 SHAKE YA TAILFEATHER Nelly & P. -

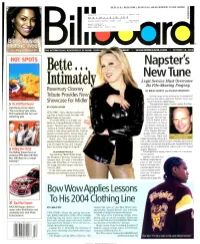

Bette... New Tune R Legit Service Must Overcome Intimately Its File -Sharing Progeny

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) 3 -DIGIT 908 #BCNCCVR * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** 111I111I111I1111I1H 1I111I11I111I111III111111II111I1 u A06 80101 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 508 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 Black Music' Historic Wee See Pages 20 and 58 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO A MENT www.billboard.com OCTOBER 18, 2003 HOT SPOTS Napster's Bette... New Tune r Legit Service Must Overcome Intimately Its File -Sharing Progeny Rosemary Clooney BY BRIAN GARRITY and JULIANA KORANTENG Tribute Provides New On the verge of resurfacing as a commercial service, the once -notorious Napster must face Showcase For Midler its own double -edged legacy. 5 The DVD That Roared The legitimate digital music market that Nap - helped force into Walt Disney Home Video's BY CHUCK TAYLOR ster existence is poised "The Lion Kng" gets deluxe NEW YORK -Barry Manilow recalls wak- to go mainstream in DVD treatment and two -year ing from a dream earlier this year with North America and plan. marketing Bette Midler on his mind. Europe. Yet the maj- "It was the 1950s in my dream, and ority of digital music Bette wa: singing Rosemary Clooney consumers in those songs," Manilow says with a smile. territories continue to "Bette and I hadn't spoken in years, but I get their music for free picked u- the phone and told her I had an from Napster -like peer- i idea for a tribute album. I knew there was to -peer (P2P) networks. absolutely no one else who could do this." In Europe, legal and GOROG: GIVING CONSUMERS WHATTHEY WANT Midle- says, "The concept was ab- illegal downloads are on the solutely billiant. -

Page 1 Senior Edition 2005

Page 2 May 20, 2005 Leaders Senior class officers: front row, Erin Hackfeld president; Kalli Wesson, vice president; back row, Corie Hernandez, sec- retary; Kayla Guerrero, treasurer. Senior Class Favorites Mr. and Miss SHS Ricky Early and Kayla Guerrero Kayla Guerrero and Israel Torrez Mr. SHS nominees Ricky Early, Logan Martin, Israel Torrez, Zack Miss SHS nominees Blake Robertson, Erin Hackfeld, Samantha Garcia and Lico Castillo. Moyers, Kayla Guerrero and Kelsey Shaw. Page 3 May 20, 2005 Shattered Dreams Marisa Munoz waits for help after being in- jured in a mock accident in the Shattered Dreams program. Photo by Alayna Alexander Play that funky music Michael Nelson plays guitar and sings during choir. Photo by Amanda Blythe Workin’ hard: seniors build, First Stroke Hope Cole works on a project in art. Photo by Kim Cooper Double time Drum major Krista Chaidez watches band members to make sure everyone is in line. Photo by Daniel Burton perform, participate Hmm... Jarrod Fletcher sorts letters in the Settin’ it in place Antwoine Cobb works on a Made for you Jerry Ashley car- teachers’ boxes as part of his duties as office project for his class. Photo by Amanda Blythe ries his TSA project, a toy box for his aide. Photo by Christi Williams niece. Photo by Nikki Timora Page 3 May 20, 2005 Shattered Dreams Marisa Munoz waits for help after being in- jured in a mock accident in the Shattered Dreams program. Photo by Alayna Alexander Play that funky music Michael Nelson plays guitar and sings during choir. Photo by Amanda Blythe Workin’ hard: seniors build, First Stroke Hope Cole works on a project in art.