T M D L IM P L E M E N T a T IO N P L a N Conowingo Creek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maryland Darter Etheostoma Sellare

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Maryland darter Etheostoma Sellare Introduction The Maryland darter is a small freshwater fish only known from a limited area in Harford County, Maryland. These areas, Swan Creek, Gashey’s Run (a tributary of Swan Creek) and Deer Creek, are part of the larger Susquehanna River drainage basin. Originally discovered in Swan Creek nymphs. Spawning is assumed to species of darters. Electrotrawling is in 1912, the Maryland darter has not occur during late April, based on other the method of towing a net from a boat been seen here since and only small species, but no Maryland darters have with electrodes attached to the net that numbers of individuals have been been observed during reproduction. send small, harmless pulses through found in Gashey’s Run and Deer the water to stir up fish. Electrofishing Creek. A Rare Species efforts in the Susquehanna are Some biologists suspect that the continuing. Due to its scarcity, the Maryland Maryland darter could be hiding darter was federally listed as in the deep, murky waters of the A lack of adequate surveying of endangered in 1967, and critical Susquehanna River. Others worry large rivers in the past due to limited habitat was designated in 1984. The that the decreased darter population technology leaves hope for finding darter is also state listed. The last is evidence that the desirable habitat Maryland darters in this area. The new known sighting of the darter was in for these fish has diminished, possibly studies would likely provide definitive 1988. due to water quality degradation and information on the population status effects of residential development of the Maryland darter and a basis for Characteristics in the watershed. -

Susquhanna River Fishing Brochure

Fishing the Susquehanna River The Susquehanna Trophy-sized muskellunge (stocked by Pennsylvania) and hybrid tiger muskellunge The Susquehanna River flows through (stocked by New York until 2007) are Chenango, Broome, and Tioga counties for commonly caught in the river between nearly 86 miles, through both rural and urban Binghamton and Waverly. Local hot spots environments. Anglers can find a variety of fish include the Chenango River mouth, Murphy’s throughout the river. Island, Grippen Park, Hiawatha Island, the The Susquehanna River once supported large Smallmouth bass and walleye are the two Owego Creek mouth, and Baileys Eddy (near numbers of migratory fish, like the American gamefish most often pursued by anglers in Barton) shad. These stocks have been severely impacted Fishing the the Susquehanna River, but the river also Many anglers find that the most enjoyable by human activities, especially dam building. Susquehanna River supports thriving populations of northern pike, and productive way to fish the Susquehanna is The Susquehanna River Anadromous Fish Res- muskellunge, tiger muskellunge, channel catfish, by floating in a canoe or small boat. Using this rock bass, crappie, yellow perch, bullheads, and method, anglers drift cautiously towards their toration Cooperative (SRFARC) is an organiza- sunfish. preferred fishing spot, while casting ahead tion comprised of fishery agencies from three of the boat using the lures or bait mentioned basin states, the Susquehanna River Commission Tips and Hot Spots above. In many of the deep pool areas of the (SRBC), and the federal government working Susquehanna, trolling with deep running lures together to restore self-sustaining anadromous Fishing at the head or tail ends of pools is the is also effective. -

Recreation on Conowingo Pond

Welcome to ABOUT Recreation on Conowingo Pond Conowingo Pond is one of the largest bodies of fresh water in the Northeast, and its shorelines possess great beauty and abundant natural resources. It’s a place where clean energy is generated, where wildlife can grow and thrive and where visitors can enjoy a great outdoor experience. Exelon Generation is proud to be caretaker of this natural resource and invites you to experience all it has to offer. MAKING THE MOST OF YOUR VISIT Conowingo Pond and the area surrounding it has a wealth of resources for the enjoyment of nature and recreational activities. The pond is one of the largest bodies of fresh water in the Northeast. On its water and along its shores you will find opportunities to boat, kayak, water ski, fish, hike, camp, and bird watch. Exelon Generation has developed several public facilities including a swimming pool, marinas, boat launches, and fishing areas. The company has also provided land to government agencies and private organizations to develop parks, marinas, and boat launches. 2 Click the buttons to make a phone call or access directions. Muddy Run Recreational Park Muddy Run Recreational Park contains a beautiful 100-acre lake surrounded by 700 acres of woods and rolling fields. 172 Bethesda Church Road 717-284-5856 West Holtwood, PA, 17532 Park Activities include camping, boating, fishing, hiking, and picnicking. Muddy Run Lake offers easy shoreline access, a boat launch as well as boat rentals. The Campground has more than 150 tent and trailer sites with picnic tables, grills, and water and electric hookups. -

Susquehanna Riyer Drainage Basin

'M, General Hydrographic Water-Supply and Irrigation Paper No. 109 Series -j Investigations, 13 .N, Water Power, 9 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR HYDROGRAPHY OF THE SUSQUEHANNA RIYER DRAINAGE BASIN BY JOHN C. HOYT AND ROBERT H. ANDERSON WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1 9 0 5 CONTENTS. Page. Letter of transmittaL_.__.______.____.__..__.___._______.._.__..__..__... 7 Introduction......---..-.-..-.--.-.-----............_-........--._.----.- 9 Acknowledgments -..___.______.._.___.________________.____.___--_----.. 9 Description of drainage area......--..--..--.....-_....-....-....-....--.- 10 General features- -----_.____._.__..__._.___._..__-____.__-__---------- 10 Susquehanna River below West Branch ___...______-_--__.------_.--. 19 Susquehanna River above West Branch .............................. 21 West Branch ....................................................... 23 Navigation .--..........._-..........-....................-...---..-....- 24 Measurements of flow..................-.....-..-.---......-.-..---...... 25 Susquehanna River at Binghamton, N. Y_-..---...-.-...----.....-..- 25 Ghenango River at Binghamton, N. Y................................ 34 Susquehanna River at Wilkesbarre, Pa......_............-...----_--. 43 Susquehanna River at Danville, Pa..........._..................._... 56 West Branch at Williamsport, Pa .._.................--...--....- _ - - 67 West Branch at Allenwood, Pa.....-........-...-.._.---.---.-..-.-.. 84 Juniata River at Newport, Pa...-----......--....-...-....--..-..---.- -

Shamokin Creek Site 48 Passive Treatment System SRI O&M TAG Project #5 Request #1 OSM PTS ID: PA-36

Passive Treatment Operation & Maintenance Technical Assistance Program June 2015 Funded by PA DEP Growing Greener & Foundation for PA Watersheds 1113102 Stream Restoration Incorporated & BioMost, Inc. Shamokin Creek Site 48 Passive Treatment System SRI O&M TAG Project #5 Request #1 OSM PTS ID: PA-36 Requesting Organization: Northumberland County Conservation District & Shamokin Creek Restoration Alliance (in-kind partners) Receiving Stream: Unnamed tributary (Shamokin Creek Watershed) Hydrologic Order: Unnamed tributaryShamokin CreekSusquehanna River Municipality/County: Coal Township, Northumberland County Latitude / Longitude: 40°46'40.152"N / 76°34'39.558"W Construction Year: 2003 The Shamokin Creek Site 48 (SC48) Passive Treatment System was constructed in 2003 to treat an acidic, metal-bearing discharge in Coal Township, Northumberland County, PA. Stream Restoration Inc. was contacted by Jaci Harner, Watershed Specialist, Northumberland County Conservation District (NCCD), on behalf of the Shamokin Creek Restoration Alliance (SCRA) via email on 8/2/2011 regarding problems with the SC48 passive system. Cliff Denholm (SRI) conducted a site investigation on 9/19/2011 with Jaci Harner and SCRA members Jim Koharski, Leanne Bjorklund, and Mike Handerhan. According to the group, the system works well; however, they were experiencing problems with the SC48 system intake pipe. An AMD- impacted stream is treated by diverting water into a passive system via a small dam and intake pipe. During storm events and high-flow periods, however, erosion with sediment transport takes place which results in a large quantity of sediment including gravel-sized material being deposited in the area above the intake as well as within the first settling pond. -

2018 Pennsylvania Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws PERMITS, MULTI-YEAR LICENSES, BUTTONS

2018PENNSYLVANIA FISHING SUMMARY Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws 2018 Fishing License BUTTON WHAT’s NeW FOR 2018 l Addition to Panfish Enhancement Waters–page 15 l Changes to Misc. Regulations–page 16 l Changes to Stocked Trout Waters–pages 22-29 www.PaBestFishing.com Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 18 Southeastern Regular Opening Day 2 TROUT OPENERS Counties March 31 AND April 14 for Trout Statewide www.GoneFishingPa.com Use the following contacts for answers to your questions or better yet, go onlinePFBC to the LOCATION PFBC S/TABLE OF CONTENTS website (www.fishandboat.com) for a wealth of information about fishing and boating. THANK YOU FOR MORE INFORMATION: for the purchase STATE HEADQUARTERS CENTRE REGION OFFICE FISHING LICENSES: 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 of your fishing P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Phone: (814) 359-5110 BOAT REGISTRATION/TITLING: license! Phone: (866) 262-8734 Phone: (717) 705-7800 Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The mission of the Pennsylvania Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday PUBLICATIONS: Fish and Boat Commission is to Monday through Friday BOATING SAFETY Phone: (717) 705-7835 protect, conserve, and enhance the PFBC WEBSITE: Commonwealth’s aquatic resources EDUCATION COURSES FOLLOW US: www.fishandboat.com Phone: (888) 723-4741 and provide fishing and boating www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia opportunities. REGION OFFICES: LAW ENFORCEMENT/EDUCATION Contents Contact Law Enforcement for information about regulations and fishing and boating opportunities. Contact Education for information about fishing and boating programs and boating safety education. -

Marcellus Shale Fracking and Susquehanna River Stakeholder Attitudes: a Five-Year Update Mark Heuer Susquehanna University

Susquehanna University Scholarly Commons Accounting Faculty Publications 9-7-2017 Marcellus Shale Fracking and Susquehanna River Stakeholder Attitudes: A Five-Year Update Mark Heuer Susquehanna University Shan Yan Susquehanna University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.susqu.edu/acct_fac_pubs Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Heuer, Mark and Yan, Shan, "Marcellus Shale Fracking and Susquehanna River Stakeholder Attitudes: A Five-Year Update" (2017). Accounting Faculty Publications. 5. https://scholarlycommons.susqu.edu/acct_fac_pubs/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. sustainability Article Marcellus Shale Fracking and Susquehanna River Stakeholder Attitudes: A Five-Year Update Mark Heuer * and Shan Yan The Sigmund Weis School of Business, Susquehanna University, Selinsgrove, PA 17870, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 September 2017; Accepted: 20 September 2017; Published: 25 September 2017 Abstract: The attitudes of Susquehanna River stakeholders regarding natural gas hydraulic fracturing (fracking) in the Marcellus Shale region reflect differing concerns on economic, social, and environmental issues based on gender, education level, and income. The focus on the U.S. State of Pennsylvania section of the Susquehanna River derives from the U.S. States of New York and Maryland, neighbors of Pennsylvania to the immediate north and south, respectively, enacting bans on fracking, while Pennsylvania has catapulted, through Marcellus fracking, to become the second largest natural gas producing state in the U.S. -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

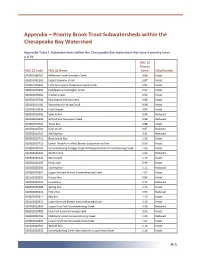

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96 -

Final Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE ................................................................................. 1 2.0 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ................................................................................... 2 3.0 DESCRIPTION OF WATERSHED .................................................................................. 3 3.1 Relationship Between Recharge and Geologic Setting .......................................... 3 4.0 APPLICATION OF USGS HYDROGEOLOGIC MODEL .............................................. 5 4.1 Discussion of Hydrogeologic Units ....................................................................... 5 4.2 Calculation of Recharge ......................................................................................... 8 5.0 COMPARISON OF CALCULATED BASE FLOW WITH STREAM FLOW DATA ... 9 5.1 Comparison with Longer-Term Stream Gage Records .......................................... 9 5.2 Comparison with More Recent Stream Gage Records ........................................ 10 5.3 Comparison with StreamStats .............................................................................. 11 6.0 IMPERVIOUS COVER ................................................................................................... 12 7.0 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .......................................................... 15 7.1 Summary and Conclusions ................................................................................... 15 7.2 Recommendations ............................................................................................... -

Lancaster County Incremental Deliveredhammer a Creekgricultural Lititz Run Lancasterload of Nitro Gcountyen Per HUC12 Middle Creek

PENNSYLVANIA Lancaster County Incremental DeliveredHammer A Creekgricultural Lititz Run LancasterLoad of Nitro gCountyen per HUC12 Middle Creek Priority Watersheds Cocalico Creek/Conestoga River Little Cocalico Creek/Cocalico Creek Millers Run/Little Conestoga Creek Little Muddy Creek Upper Chickies Creek Lower Chickies Creek Muddy Creek Little Chickies Creek Upper Conestoga River Conoy Creek Middle Conestoga River Donegal Creek Headwaters Pequea Creek Hartman Run/Susquehanna River City of Lancaster Muddy Run/Mill Creek Cabin Creek/Susquehanna River Eshlemen Run/Pequea Creek West Branch Little Conestoga Creek/ Little Conestoga Creek Pine Creek Locally Generated Green Branch/Susquehanna River Valley Creek/ East Branch Ag Nitrogen Pollution Octoraro Creek Lower Conestoga River (pounds/acre/year) Climbers Run/Pequea Creek Muddy Run/ 35.00–45.00 East Branch 25.00–34.99 Fishing Creek/Susquehanna River Octoraro Creek Legend 10.00–24.99 West Branch Big Beaver Creek Octoraro Creek 5.00–9.99 Incremental Delivered Load NMap (l Createdbs/a byc rThee /Chesapeakeyr) Bay Foundation Data from USGS SPARROW Model (2011) Conowingo Creek 0.00–4.99 0.00 - 4.99 cida.usgs.gov/sparrow Tweed Creek/Octoraro Creek 5.00 - 9.99 10.00 - 24.99 25.00 - 34.99 35.00 - 45.00 Map Created by The Chesapeake Bay Foundation Data from USGS SPARROW Model (2011) http://cida.usgs.gov/sparrow PENNSYLVANIA York County Incremental Delivered Agricultural YorkLoad Countyof Nitrogen per HUC12 Priority Watersheds Hartman Run/Susquehanna River York City Cabin Creek Green Branch/Susquehanna -

American Eel: Collection and Relocation Conowingo Dam, Susquehanna River, Maryland 2016

American Eel: Collection and Relocation Conowingo Dam, Susquehanna River, Maryland 2016 Chris Reily, Biological Science Technician, MD Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office, USFWS Steve Minkkinen, Project Leader, MD Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office, USFWS 1 BACKGROUND The American Eel (Anguilla rostrata) is the only species of freshwater eel in North America and originates from the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic Ocean (USFWS 2011). The eels are catadromous, hatching in saltwater and maturing in freshwater before returning to their natal waters to spawn. Larval eels (referred to as leptocephalus larvae) are transported throughout the eastern seaboard via ocean currents where their range extends from Brazil to Greenland. By the time the year-long journey to the coast is over, they have matured into the “glass eel” phase and have developed fins and taken on the overall shape of the adults (Hedgepath 1983). After swimming upstream into continental waters, the 5-8 cm glass eels mature into “elvers” at which time they take on a green-brown to gray pigmentation and grow beyond 10 cm in length (Haro and Krueger 1988). Elvers migrate upstream into estuarine and riverine environments where they will remain as they change into sexually immature “yellow eels”. Yellow eels have a yellow-green to olive coloration and will typically remain in this stage for three to 20 years before reaching the final stage of maturity. The eels may begin reaching sexual maturity when they reach at least 25 cm in length and are called “silver eels”. Silver eels become darker on the dorsal side and silvery or white on the ventral side and continue to grow as they complete their sexual maturation.