Towards a Further Understanding of the Violence Experienced By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Government's Executions Policy During the Irish Civil

THE GOVERNMENT’S EXECUTIONS POLICY DURING THE IRISH CIVIL WAR 1922 – 1923 by Breen Timothy Murphy, B.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisor of Research: Dr. Ian Speller October 2010 i DEDICATION To my Grandparents, John and Teresa Blake. ii CONTENTS Page No. Title page i Dedication ii Contents iii Acknowledgements iv List of Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The ‗greatest calamity that could befall a country‘ 23 Chapter 2: Emergency Powers: The 1922 Public Safety Resolution 62 Chapter 3: A ‗Damned Englishman‘: The execution of Erskine Childers 95 Chapter 4: ‗Terror Meets Terror‘: Assassination and Executions 126 Chapter 5: ‗executions in every County‘: The decentralisation of public safety 163 Chapter 6: ‗The serious situation which the Executions have created‘ 202 Chapter 7: ‗Extraordinary Graveyard Scenes‘: The 1924 reinterments 244 Conclusion 278 Appendices 299 Bibliography 323 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my most sincere thanks to many people who provided much needed encouragement during the writing of this thesis, and to those who helped me in my research and in the preparation of this study. In particular, I am indebted to my supervisor Dr. Ian Speller who guided me and made many welcome suggestions which led to a better presentation and a more disciplined approach. I would also like to offer my appreciation to Professor R. V. Comerford, former Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for providing essential advice and direction. Furthermore, I would like to thank Professor Colm Lennon, Professor Jacqueline Hill and Professor Marian Lyons, Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for offering their time and help. -

Centenary Timeline for the County of Cork (1920 – 1923)

CENTENARY TIMELINE FOR THE COUNTY OF CORK (1920 – 1923) – WAR OF INDEPENDENCE AND CIVIL WAR Guidance Note: This document provides hundreds of key dates with regard to the involvement of County Cork in the War of Independence and Civil War. These include the majority of the key occurrences of 1920 – 1923 including all major events from the County of Cork (including some other locations that involved people from County Cork), as well as key developments on the national level (or elsewhere in the country) during this timeframe (blue). All key ambushes, attacks and executions are included as well as events that saw the loss of life of Cork people, whether in Cork County or further afield. A number of notable events pertaining to Cork City (note: not all) are also included (green) and a details/link section is provided to indicate the source material. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information contained within this document, given the volume of material and variations in the historical record, there will undoubtedly be errors, omissions and other such issues. It is the intention of Cork County Council’s Commemorations Committee that this will remain a ‘live document’ and all suggested additional dates/amendments/etc. are most welcome, with this document being continually updated as appropriate. Cork County Council’s Commemorations Committee recognises and wishes to pay tribute to the excellent research already undertaken by some excellent scholars regarding this time period and looks forward to further correspondence from community groups and other interested persons. It is the purpose of this document to provide such dates that will assist local community groups in the organising of their local centenary events. -

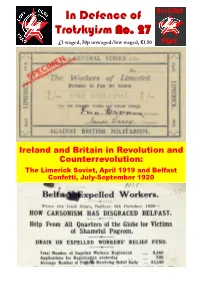

In Defence of Trotskyism No. 27 £1 Waged, 50P Unwaged/Low Waged, €1.50

In Defence of Trotskyism No. 27 £1 waged, 50p unwaged/low waged, €1.50 2 to ‘No Platform’ fascists but we never call on the Socialist Fight Where We capitalist state to ban fascist marches or parties; these laws would inevitably primarily be used against work- Stand (extracts) ers’ organisations, as history has shown. 1. We stand with Karl Marx: ‘The emancipation of the 14. We oppose all immigration controls. International working classes must be conquered by the working finance capital roams the planet in search of profit and classes themselves. The struggle for the emancipation imperialist governments disrupts the lives of workers of the working class means not a struggle for class and cause the collapse of whole nations with their privileges and monopolies but for equal rights and direct intervention in the Balkans, Iraq and Afghani- duties and the abolition of all class rule’ (The Interna- stan and their proxy wars in Somalia and the Demo- tional Workingmen’s Association 1864, General cratic Republic of the Congo, etc. Workers have the Rules). The working class ‘cannot emancipate itself right to sell their labour internationally wherever they without emancipating itself from all other sphere of get the best price. society and thereby emancipating all other spheres of 19. As socialists living in Britain we take our responsi- society’ (Marx, A Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s bilities to support the struggle against British imperial- Philosophy of Right, 1843). ism’s occupation of the six north-eastern counties of 9. We are completely opposed to man-made climate Ireland very seriously. -

Moss Twomey Papers

Moss Twomey Papers P69 UCD Archives School of History and Archives archives @ucd.ie www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 1992 University College Dublin. All rights reserved Introduction vii. Abbreviations x. MOSS TWOMEY PAPERS: content and structure I. CHIEF OF STAFF A. Orders and Directives, 1922-26 1 B. Communications with Government and Army i. With Government and GHQ Departments, 1922-26 a. Minister for Defence 2 b. Assistant Chief of Staff 3 c. Adjutant General 3 d. Quartermaster General 4 e. Director of Intelligence 5 f. Director of Organisation 6 g. Director of Engineering 7 h. Director of Publicity 7 j. Director of Signalling 8 k. Director of Communications 9 ii. With Army Units, 1922-25 a. Dublin 1 Brigade 9 b. Dublin 2 Brigade 11 c. Midland Division 11 d. 1 Southern Division 12 e. 3 Southern Division 13 f. Western Command 15 g. 2 Western Division 15 h. 3 Western Division 16 j. 4 Western Division 16 k. Northern Command/4 Northern 16 Division l. Belfast Brigade 17 m. Britain, Scotland and U.S. 17 iii. General and Unsorted Communications, 1922-33 18 iv. Chief of Staff’s Occasional Correspondence 27 iii C. Communications with Related Organisations, 1923-28 i. Sinn Féin 30 ii. Irish Republican Prisoners’ Dependents’ Fund 31 iii. White Cross 31 iv. Cumann na mBan 32 D. Post Records, 1923-32 32 E. History of the I.R.A., 1927 33 II. ADJUTANT GENERAL A. Orders and Directives, 1922-27 34 B. Communications with Government and Army i. -

Civil War Violence in Kerry

Civil War Violence in Kerry A Necessary First Principle Fig.1- Execution of Rory O’Connor, Dublin 8 Dec’ 1922 (Courtesy of Roddy McCorley Museum) Submitted in fulfilment of the Requirements for the Research Masters Dissertation History (Political Culture and National Identities), Leiden University Orson McMahon S1652826 ii Table of Contents List of Figures iv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Historiography 7 2.1 Irreconcilable Differences 7 2.2 Towards an Academic Account 10 2.3 Conclusion 14 Chapter 3 Civil War Theory 16 3.1 Introduction 16 3.2 Traditional Theories of Civil War 18 3.3 Explaining Violence 22 Chapter 4 A Clean Fight - The IRA 25 4.1 Introduction 25 4.2 Overview of Violence 31 4.3 ‘Kerry, The Plague Spot’ 34 4.4 Expanding Bullets 45 4.5 Conclusion 50 Chapter 5 Indiscipline and The National Army 53 5.1 Defining Discipline 53 5.2 Amicicide - Killing One’s Own 56 5.3 Sending a Message 62 5.4 Landmine Killings 66 5.5 Extra-Judicial Killing Throughout the Conflict 77 5.6 Beyond the End 83 5.7 Conclusion 86 Chapter 6 Conclusion 88 Bibliography 94 Appendices 100 iii List of Figures 1. Execution of Rory O’Connor, Dublin, 8 December 1922 2. Map showing National Army operations throughout Kerry, August 1922 3. Republican Civil War handbill 4. Contemporary propaganda cartoon depicting ‘Trucileers’ 5. Total National Army deaths killed by IRA by month 6. Total controversial killings of National Army by IRA by month 7. Mass card of Edward Noone (National Army) 8.