Steve Reich. Resonances of an Origin Carmen Pardo Salgado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signumclassics YELLOW Catalogue No

CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer: SignumClassics YELLOW Catalogue No. SIGCD064 BLACK Job Title: Differnt Trains SIGCD064 booklet Page Nos. ALSO on signumclassics Michael Nyman: Cantos Sagrados: Elena Kats-Chernin: Music for Two Pianos SIGCD506 The Music of James MacMillan SIGCD507 Ragtime & Blue SIGCD058 “This duo is never less than vital, bold and “Choral works that show MacMillan’s powerful Elena Kats-Chernin is a composer who defies cat- committed” International Record Review voice at its most engaging” The Gramophone egorisation. A cornucopia of rags, blues and heart-melting melodies, these small vessels of fine feelings offer an intimate view into the com- poser’s heart. Available through most record stores and at www.signumrecords.com. For more information call +44 (0) 20 8997 4000 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer: SignumClassics YELLOW Catalogue No. SIGCD064 BLACK Job Title: Differnt Trains SIGCD064 booklet Page Nos. different trains Triple Quartet 1. I [7.11] 2. II [4.05] 3. III [3.31] 4. Duet [5.14] Different Trains 5. America - Before the war [9.00] 6. Europe - During the war [7.29] 7. After the war [10.25] Total Time [46.59] Two major international forces at the leading edge of contemporary music – the Smith Quartet and American composer Steve Reich - come together for new recordings of three of his most inspiring works: Triple Quartet for three string quartets, Reich’s personal dedication to the late Yehudi Menuhin, Duet, and the haunting Different Trains for string quartet and electronic tape. -

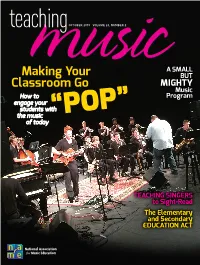

Making Your Classroom Go

teaching OCTOBER 2015 VOLUME 23, NUMBER 2 A SMALL Makingmusicmusic Your BUT Classroom Go MIGHTY Music How to Program engage your students with the music “POP” of today TEACHING SINGERS to Sight-Read The Elementary and Secondary EDUCATION ACT QuaverFindOutAd_NAfME_Aug15.pdf 1 7/30/15 12:26 PM Find out what these districts already know... Quaver is revolutionizing music education! TM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Packed with nearly 1,000 Songs! Try 36 Lessons from our K-8 Curriculum! Just go to QuaverMusic.com/Preview and begin your FREE 30-day trial today! ©2015 QuaverMusic.com, LLC October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 contentsMUSIC EDUCATION ● ORCHESTRATING SUCCESS Music students learn cooperation, discipline, and teamwork. 28 Teachers and students alike can rock out and learn with pop music! FEATURES 24 TEACHING SINGERS 28 POP AND ROCK GOES 32 EL SISTEMA TODAY 38 SMALL SCHOOL, TO READ THE PROGRAM! José Antonio Abreu’s BIG EFFORT, Instructing students in Pop music connects creation has taken GREAT SUCCESS the art and techniques instantly with many root in the U.S. and Alexandria Hanessian’s of sight-singing can reap students. How can continues to grow small but mighty middle many rewards in your music educators use through programs such school program thrives choral rehearsals and it in their classrooms as the Corona Youth in Spencertown, beyond. to increase student Music Project and New York. engagement? Juneau Alaska Music Matters. Photo by Little Kids Rock. Photo by nafme.org 1 October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 Student composers contents (far left and right) work with teachers Conductor Marin Alsop 56 at Williamsville East works with students in High School. -

Teaching Guide: Area of Study 7

Teaching guide: Area of study 7 – Art music since 1910 This resource is a teaching guide for Area of Study 7 (Art music since 1910) for our A-level Music specification (7272). Teachers and students will find explanations and examples of all the musical elements required for the Listening section of the examination, as well as examples for listening and composing activities and suggestions for further listening to aid responses to the essay questions. Glossary The list below includes terms found in the specification, arranged into musical elements, together with some examples. Melody Modes of limited transposition Messiaen’s melodic and harmonic language is based upon the seven modes of limited transposition. These scales divide the octave into different arrangements of semitones, tones and minor or major thirds which are unlike tonal scales, medieval modes (such as Dorian or Phrygian) or serial tone rows all of which can be transposed twelve times. They are distinctive in that they: • have varying numbers of pitches (Mode 1 contains six, Mode 2 has eight and Mode 7 has ten) • divide the octave in half (the augmented 4th being the point of symmetry - except in Mode 3) • can be transposed a limited number of times (Mode 1 has two, Mode 2 has three) Example: Quartet for the End of Time (movement 2) letter G to H (violin and ‘cello) Mode 3 Whole tone scale A scale where the notes are all one tone apart. Only two such scales exist: Shostakovich uses part of this scale in String Quartet No.8 (fig. 4 in the 1st mvt.) and Messiaen in the 6th movement of Quartet for the End of Time. -

Different Trains

DIFFERENT TRAINS 2018 / 2019 Concert Series FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Soundstreams audiences are accustomed each written compelling string works: Dorothy to programs that pursue themes: musical, Chang (Vancouver), “Streams” for solo viola; extra-musical and sometimes both. This and Rolf Wallin (Oslo, Norway), “Curiosity program does both, a direct result of a chance Cabinet” and “Swans Kissing,” each for string meeting on the street with violinist and coach quartet. We programmed these three works and par excellence Barry Shiffman. Barry has been invited both composers (and the Rolstons!) to a mentor to the impressive Rolston String be in residence for the ECW, which will Quartet, and mentioned they had rights for conclude tomorrow morning after ten intensive a limited time to a recent video created for days. Rounding out tonight’s program is one of Steve Reich’s iconic “Different Trains.” R. Murray Schafer’s most beloved works, his “String Quartet #2 (Waves)”. While we have programmed a number of Reich’s best known works, often in his presence, never In terms of extra-musical themes, our insightful have we presented “Different Trains,” and the colleague David Jaeger has pointed out in his opportunity to present it with the Rolstons in this program note that several of tonight’s works are special version with video proved irresistible. themed around water. And Reich’s Different So repertoire for strings became the evening’s Trains bears musical witness to the Holocaust, clear musical theme. one of the possible responses to philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno’s assertion that At the same time we made that decision, we “poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” were looking for visiting mentors for our annual Emerging Composers Workshop (ECW). -

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:07 p.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Article abstract Volume 21, Number 2, 2011 This essay offers broad reflection on some of the challenges faced by African composers of art music. The specific point of departure is the publication of a URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar new anthology, Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Ghanaian pianist and scholar William Chapman Nyaho and published in 2009 by Oxford University Press. The anthology exemplifies a diverse range of See table of contents creative achievement in a genre that is less often associated with Africa than urban ‘popular’ music or ‘traditional’ music of pre-colonial origins. Noting the virtues of musical knowledge gained through individual composition rather than ethnography, the article first comments on the significance of the Publisher(s) encounters of Steve Reich and György Ligeti with various African repertories. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Then, turning directly to selected pieces from the anthology, attention is given to the multiple heritage of the African composer and how this affects his or her choices of pitch, rhythm and phrase structure. Excerpts from works by Nketia, ISSN Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi and Osman serve as illustration. 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Agawu, K. (2011). The Challenge of African Art Music. Circuit, 21(2), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

ZGMTH - the Order of Things

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bangor University Research Portal The Order of Things. Analysis and Sketch Study in Two Works by Steve ANGOR UNIVERSITY Reich Bakker, Twila; ap Sion, Pwyll Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie DOI: 10.31751/1003 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 01/06/2019 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Bakker, T., & ap Sion, P. (2019). The Order of Things. Analysis and Sketch Study in Two Works by Steve Reich. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie, 16(1), 99-122. https://doi.org/10.31751/1003 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 09. Oct. 2020 ZGMTH - The Order of Things https://www.gmth.de/zeitschrift/artikel/1003.aspx Inhalt (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/inhalt.aspx) Impressum (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/impressum.aspx) Autorinnen und Autoren (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/autoren.aspx) Home (/home.aspx) Bakker, Twila / ap Siôn, Pwyll (2019): The Order of Things. -

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First I

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First International Conference on Music and Minimalism University of Wales, Bangor Friday, August 31, 2007 Minimalism is perhaps one of the most misunderstood musical movements of the latter half of the twentieth century. Even among musicians, there is considerable disagreement as to the meaning of the term “minimalism” and which pieces should be categorized under this broad heading.1 Furthermore, minimalism is often referenced using negative terminology such as “trance music” or “stuck-needle music.” Yet, its impact cannot be overstated, influencing both composers of art and rock music. Within the original group of minimalists, consisting of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass2, the latter two have received considerable attention and many of their works are widely known, even to non-musicians. However, Terry Riley is one of the most innovative members of this auspicious group, and yet, he has not always received the appropriate recognition that he deserves. Most musicians familiar with twentieth century music realize that he is the composer of In C, a work widely considered to be the piece that actually launched the minimalist movement. But is it really his first minimalist work? Two pieces that Riley wrote early in his career as a graduate student at Berkeley warrant closer attention. Riley composed his String Quartet in 1960 and the String Trio the following year. These two works are virtually unknown today, but they exhibit some interesting minimalist tendencies and indeed foreshadow some of Riley’s later developments. -

Review of Rethinking Reich, Edited by Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll Ap Siôn (Oxford University Press, 2019) *

Review of Rethinking Reich, Edited by Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll ap Siôn (Oxford University Press, 2019) * Orit Hilewicz NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hilewicz.php KEYWORDS: Steve Reich, analysis, politics DOI: 10.30535/mto.27.1.0 Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory [1] This past September, a scandal erupted on social media when a 2018 book excerpt was posted that showed a few lines from an interview with British photographer and music writer Val Wilmer. Wilmer recounted her meeting with Steve Reich in the early 1970s: I was talking about a person who was playing with him—who happened to be an African-American who was a friend of mine. I can tell you this now because I feel I must . we were talking and I mentioned this man, and [Reich] said, “Oh yes, well of course, he’s one of the only Blacks you can talk to.” So I said, “Oh really?” He said, “Blacks are geing ridiculous in the States now.” And I thought, “This is a man who’s just done this piece called Drumming which everybody cites as a great thing. He’s gone and ripped off stuff he’s heard in Ghana—and he’s telling me that Blacks are ridiculous in the States now.” I rest my case. Wouldn’t you be politicized? (Wilmer 2018, 60) Following recent revelations of racist and misogynist statements by central musical figures and calls for music scholarship to come to terms with its underlying patriarchal and white racial frame, (1) the new edited volume on Reich suggests directions music scholarship could take in order to examine the political, economic, and cultural environments in which musical works are composed, performed, and received. -

Reconsidering the Nineteenth-Century Potpourri: Johann Nepomuk Hummel’S Op

Reconsidering the Nineteenth-Century Potpourri: Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Op. 94 for Viola and Orchestra A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2018 by Fan Yang B. M., Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, 2008 M. M., Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, 2010 D. M. A. Candidacy, University of Cincinnati, 2013 Abstract The Potpourri for Viola and Orchestra, Op. 94 by Johann Nepomuk Hummel is available in a heavily abridged edition, entitled Fantasy, which causes confusions and problems. To clarify this misperception and help performers choose between the two versions, this document identifies the timeline and sources that exist for Hummel’s Op. 94 and compares the two versions of this work, focusing on material from the Potpourri missing in the Fantasy, to determine in what ways it contributes to the original work. In addition, by examining historical definitions and composed examples of the genre as well as philosophical ideas about the faithfulness to a work—namely, idea of the early nineteenth-century work concept, Werktreue—as well as counter arguments, this research aims to rationalize the choice to perform the Fantasy or Potpourri according to varied situations and purposes, or even to suggest adopting or adapting the Potpourri into a new version. Consequently, a final goal is to spur a reconsideration of the potpourri genre, and encourage performers and audiences alike to include it in their learning and programming. -

“Classical” Minimalism

from Richard Taruskin, “Oxford History of Western Music Volume V: Music in the Late Twentieth Century; Chapter 8: A Harmonious Avant-Garde?”. Retrieved 4/29/2011 from oxfordwesternmusic.com. “CLASSICAL” MINIMALISM For many listeners, the most characteristic and style-defining aspect of In C is the constant audible eighth-note pulse that underlies and coordinates all of the looping, and that seems, because it provides a constant pedal of Cs, to be fundamentally bound up with the work's concept. Like much modernist practice since at least Stravinsky, it puts the rhythmic spotlight on the “subtactile” level, accommodating and facilitating the free metamorphosis of the felt beat —for example, from quarters to dotted quarters at the twenty-second module of In C—and allows their multiple presence to be felt as levels within a complex texture. It may be surprising, therefore, to learn that the constant C-pulse was an afterthought, adopted in rehearsal for what seemed at the time a purely utilitarian purpose (simply to keep the group together in lieu of a conductor), and that it was not even Riley's idea. It was Reich's. Steve Reich came from a background very different from Young's and Riley's. Where they had a rural, working-class upbringing on the West Coast, Reich was born into a wealthy, professional- class family in cosmopolitan New York. Like most children of his economic class, Reich had traditional piano lessons and plenty of exposure to what in later years he mildly derided as the “bourgeois classics.” He had an elite education culminating in a Cornell baccalaureate with a major in philosophy. -

A Nonesuch Retrospective

STEVE REICH PHASES A N O nes U ch R etr O spective D isc One D isc T W O D isc T hree MUSIC FOR 18 MUSICIANS (1976) 67:42 DIFFERENT TRAINS (1988) 26:51 YOU ARE (VARIATIONS) (2004) 27:00 1. Pulses 5:26 1. America—Before the war 8:59 1. You are wherever your thoughts are 13:14 2. Section I 3:58 2. Europe—During the war 7:31 2. Shiviti Hashem L’negdi (I place the Eternal before me) 4:15 3. Section II 5:13 3. After the war 10:21 3. Explanations come to an end somewhere 5:24 4. Section IIIA 3:55 4. Ehmor m’aht, v’ahsay harbay (Say little and do much) 4:04 5. Section IIIB 3:46 Kronos Quartet 6. Section IV 6:37 David Harrington, violin Los Angeles Master Chorale 7. Section V 6:49 John Sherba, violin Grant Gershon, conductor 8. Section VI 4:54 Hank Dutt, viola Phoebe Alexander, Tania Batson, Claire Fedoruk, Rachelle Fox, 9. Section VII 4:19 Joan Jeanrenaud, cello Marie Hodgson, Emily Lin, sopranos 10. Section VIII 3:35 Sarona Farrell, Amy Fogerson, Alice Murray, Nancy Sulahian, 11. Section IX 5:24 TEHILLIM (1981) 30:29 Kim Switzer, Tracy Van Fleet, altos 12. Section X 1:51 4. Part I: Fast 11:45 Pablo Corá, Shawn Kirchner, Joseph Golightly, Sean McDermott, 13. Section XI 5:44 5. Part II: Fast 5:54 Fletcher Sheridan, Kevin St. Clair, tenors 14. Pulses 6:11 6. Part III: Slow 6:19 Geri Ratella, Sara Weisz, flutes 7.