Statement of Commissioner Rohit Chopra Joined by Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transforming Our Business

Transforming our business A cigarette manufacturing line (on the left-hand side) and a heated tobacco unit manufacturing line (on the right-hand side) at our factory in Neuchâtel, Switzerland Replacing cigarettes with While several attempts have been made to develop better alternatives to smoking, smoke-free products drawbacks in the technological capability of these products and a lack of consumer In 2017, PMI manufactured and shipped acceptance rendered them unsuccessful. 791 billion cigarettes and other Recent advances in science and combustible tobacco products and technology have made it possible to 36 billion smoke‑free products, reaching develop innovative products that approximately 150 million adult consumers consumers accept and that are less in more than 180 countries. harmful alternatives to continued smoking. Smoking cigarettes causes serious PMI has developed a portfolio of disease. Smokers are far more likely smoke‑free products, including heated Contribution of Smoke-Free than non‑smokers to get heart disease, tobacco products and nicotine‑containing Products to PMI’s Total lung cancer, emphysema, and other e‑vapor products that have the potential diseases. Smoking is addictive, and it Net Revenues to significantly reduce individual risk and 13% can be very difficult to stop. population harm compared to cigarettes. The best way to avoid the harms of Many stakeholders have asked us about smoking is never to start, or to quit. the role of these innovative smoke‑free But much more can be done to improve products in the context of our business the health and quality of life of those vision. Are these products an extension of who continue to use nicotine products, our cigarette product portfolio? Are they through science and innovation. -

North Dakota Office of State Tax Commissioner Tobacco Directory List of Participating Manufacturers (Listing by Brand) As of May 24, 2019

North Dakota Office of State Tax Commissioner Tobacco Directory List of Participating Manufacturers (Listing by Brand) As of May 24, 2019 **RYO: Roll-Your-Own Brand Name Manufacturer 1839 U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 RYO U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1st Class U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. American Bison RYO Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC Amsterdam Shag RYO Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S Ashford RYO Von Eicken Group Bali Shag RYO Commonwealth Brands, Inc. Baron American Blend Farmer’s Tobacco Co of Cynthiana, Inc. Basic Philip Morris USA, Inc. Benson & Hedges Philip Morris USA, Inc. Black & Gold Sherman’s 1400 Broadway NYC, LLC Bo Browning RYO Top Tobacco, LP Bugler RYO Scandinavian Tobacco Group Lane Limited Bull Brand RYO Von Eicken Group Cambridge Philip Morris USA, Inc. Camel R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Camel Wides R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Canoe RYO Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC Capri R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Carlton R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company CF Straight Virginia RYO Von Eicken Group Charles Fairmon RYO Von Eicken Group Chesterfield Philip Morris USA, Inc. Chunghwa Konci G & D Management Group (USA) Inc. Cigarettellos Sherman’s 1400 Broadway NYC, LLC Classic Sherman’s 1400 Broadway NYC, LLC Classic Canadian RYO Top Tobacco, LP Commander Philip Morris USA, Inc. Crowns Commonwealth Brands Inc. Custom Blends RYO Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC Brand Name Manufacturer Danish Export RYO Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S Dark Fired Shag RYO Von Eicken Group Dave’s Philip Morris USA, Inc. Davidoff Commonwealth Brands, Inc. Djarum P.T. -

Sampoerna University

SU Catalogue 2018-2019 1 WELCOME TO SAMPOERNA UNIVERSITY Welcome to Sampoerna University. We would like to congratulate each of you, our students, for your achievement in As the future of Indonesia lies in your hands, we hope that you will use your time becoming a member of the Sampoerna University community. here at Sampoerna University to gain the knowledge and skills required when you enter the professional world. It is a world where you will have to compete in Sampoerna University will provide you with an international education as you the labor force in all the ASEAN countries and beyond. study the discipline of your choice. We have established collaborations with overseas universities to ensure that you will have a pathway to your future In addition to knowledge, we hope that you will develop comprehensive social with international recognition. Our campus is the ideal place for developing and skills and moral values that will empower you to make meaningful contributions achieving your intellectual potential. to your community. Social competencies include empathy and awareness of other people, ability to listen to and understand disparate views, as well as to You will follow the learning process in different study programs in a broad range communicate across social differences. With these social competencies, we are of subjects. However, the variety of these subjects should not segregate you from confident that our students can work as a team, assume constructive roles in your fellow students undertaking other study programs. The interdisciplinary the community, and become wise and caring human beings. courses and dialogue between all fields of study are at the core of our curriculum. -

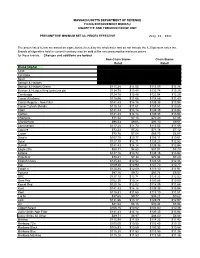

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

Altria Group, Inc. 2013 Annual Report

Altria Group, Inc. 2013 Annual Report altria.com Altria’s Operating Companies Philip Morris USA Inc. (PM USA) Philip Morris USA is the largest tobacco company in the U.S. and has about half of the U.S. cigarette market’s retail share. Altria Group, Inc. U.S. Smokeless Tobacco Company LLC (USSTC) U.S. Smokeless Tobacco Company is the n an Altria Company largest producer and marketer of moist Annual Report 2013 smokeless tobacco, one of the fastest growing tobacco segments in the U.S. John Middleton Co. (Middleton) John Middleton is a leading manufacturer of machine-made large cigars and pipe tobacco. Ste. Michelle Wine Estates Ltd. (Ste. Michelle) Ste. Michelle Wine Estates ranks among the top-ten producers of premium wines in the U.S. Nu Mark LLC (Nu Mark) Nu Mark is focused on responsibly developing and marketing innovative tobacco products for adult tobacco consumers. Philip Morris Capital Corporation (PMCC) Philip Morris Capital Corporation manages an existing portfolio of leveraged and direct finance lease investments. Altria Group, Inc. 6601 W. Broad Street Richmond, VA 23230-1723 Our Mission is to own and develop financially disciplined Shareholder Information businesses that are leaders in responsibly providing adult tobacco and wine consumers with superior branded products. Shareholder Response Center: Direct Stock Purchase and If you do not have Internet Stock Computershare Trust Company, Dividend Reinvestment Plan: access, you may call: Exchange Listing: N.A. (Computershare), our trans- Altria Group, Inc. offers a Direct 1-804-484-8222 The principal stock fer agent, will be happy to answer Stock Purchase and Dividend exchange on which questions about your accounts, Reinvestment Plan, administered Internet Access Altria Group, Inc.’s certificates, dividends or the by Computershare. -

Consumer Perceived Value Analysis of New & Incumbent Brands Of

www.sbm.itb.ac.id/ajtm The Asian Journal of Technology Management Vol. 3 No. 1 (2010) 18-33 Consumer Perceived Value Analysis of New & Incumbent Brands of Gudang Garam & Sampoerna Reza A. Nasution*1, Ifad Ardin1 1School of Business and Management, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia ABSTRACT Gudang Garam and Sampoerna are the biggest cigarette companies in Indonesia. Both of them haveboth incumbent and new brands. Gudang Garam has Surya 16 as its incumbent brand and just released Surya Slim as its new brand, while Sampoerna has A Mild as its incumbent brand and introduced Avolution as its new brand. The companies pursued different approaches in introducing the new brands.Print ads are the main source of information about their strategy. It conveys messages about value to be offfered to the market. Analysis of visual and text or copy elements of the ads are analyzed and mapped into the Consumer Perceived Value (CPV) framework from Sweeney & Soutar. The framework is divided into four dimensions: emotional, social, quality and value for money. Qualitative analysis shows how the two companies introduced their new brands and its relation to the incumbent brands. Keywords:brand, innovation, consumer perceived value, advertising, cigarette industry 1. Introduction market leader should understand for three principles. Operational excellence means Competition always happens in every efficiently, consistently and cost effectively industry, including cigarette industry. Cigarette providing a limited range of standard or routine industry is interesting. Brand in this industry is services. Customer intimacy means developing numerous for incumbent yet new brand. The and maintaining intimate relationships with brands grow constantly every year. -

Directory for Cigarettes and Roll-Your-Own Tobacco

DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL STATE OF HAWAI‘I DIRECTORY FOR CIGARETTES AND ROLL-YOUR-OWN TOBACCO of Certified Tobacco Product Manufacturers Brands and Brand Families (Available at: http://ag.hawaii.gov/cjd/tobacco-enforcement-unit/) DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL TOBACCO ENFORCEMENT UNIT 425 QUEEN STREET HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I 96813 (808) 586-1203 INDEX I. Directory: Cigarettes and Roll-Your-Own Tobacco Page 1.INTRODUCTION 3 2.DEFINITIONS 3 3.NOTICES 6 II. Summary for Directory Posted December 15, 2019* III. Alphabetical Brand List IV. Compliant Participating Manufacturers List V. Compliant Non-Participating Manufacturers List Posted: December 15, 2019 (last update October 15, 2019) 2 1. INTRODUCTION Pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat. §245-22.5(a), beginning December 1, 2003, it shall be unlawful for an entity to (1) affix a stamp to a package or other container of cigarettes belonging to a tobacco product manufacturer or brand family not included in this directory, or (2) import, sell, offer, keep, store, acquire, transport, distribute, receive, or possess for sale or distribution cigarettes1 belonging to a tobacco product manufacturer or brand family not included in this directory. Pursuant to §245-22.5(b), any entity that knowingly violates subsection (a) shall be guilty of a class C felony. Pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat. §§245-40 and 245-41, any cigarettes unlawfully possessed, kept, stored, acquired, transported, sold, imported, offered, received, or distributed in violation of Haw. Rev. Stat. Chapter 245 may be seized, confiscated, and ordered forfeited pursuant to Haw. Rev. Stat., Chapter 712A. In addition, the attorney general may apply for a temporary or permanent injunction restraining any person from violating or continuing to violate Haw. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

Page 1 of 15

Updated September14, 2021– 9:00 p.m. Date of Next Known Updates/Changes: *Please print this page for your own records* If there are any questions regarding pricing of brands or brands not listed, contact Heather Lynch at (317) 691-4826 or [email protected]. EMAIL is preferred. For a list of licensed wholesalers to purchase cigarettes and other tobacco products from - click here. For information on which brands can be legally sold in Indiana and those that are, or are about to be delisted - click here. *** PLEASE sign up for GovDelivery with your EMAIL and subscribe to “Tobacco Industry” (as well as any other topic you are interested in) Future lists will be pushed to you every time it is updated. *** https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/INATC/subscriber/new RECENTLY Changed / Updated: 09/14/2021- Changes to LD Club and Tobaccoville 09/07/2021- Update to some ITG list prices and buydowns; Correction to Pall Mall buydown 09/02/2021- Change to Nasco SF pricing 08/30/2021- Changes to all Marlboro and some RJ pricing 08/18/2021- Change to Marlboro Temp. Buydown pricing 08/17/2021- PM List Price Increase and Temp buydown on all Marlboro 01/26/2021- PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO GOVDELIVERY EMAIL LIST TO RECEIVE UPDATED PRICING SHEET 6/26/2020- ***RETAILER UNDER 21 TOBACCO***(EFF. JULY 1) (on last page after delisting) Minimum Minimum Date of Wholesale Wholesale Cigarette Retail Retail Brand List Manufacturer Website Price NOT Price Brand Price Per Price Per Update Delivered Delivered Carton Pack Premier Mfg. / U.S. 1839 Flare-Cured Tobacco 7/15/2021 $42.76 $4.28 $44.00 $44.21 Growers Premier Mfg. -

Altria Reports 2019 Third-Quarter and Nine-Months Results; Announces New 2020 - 2022 Adjusted Diluted Eps Growth Objective to Advance Strategic Business Platform

ALTRIA REPORTS 2019 THIRD-QUARTER AND NINE-MONTHS RESULTS; ANNOUNCES NEW 2020 - 2022 ADJUSTED DILUTED EPS GROWTH OBJECTIVE TO ADVANCE STRATEGIC BUSINESS PLATFORM RICHMOND, Va. - October 31, 2019 - Altria Group, Inc. (Altria) (NYSE: MO) today announces its 2019 third- quarter and nine-months business results, reaffirms its 2019 full-year adjusted diluted earnings per share guidance and announces a new 2020 - 2022 adjusted diluted earnings per share growth objective. “Our core tobacco businesses delivered excellent third-quarter financial results,” said Howard Willard, Altria’s Chairman and Chief Executive Officer. “Our 2019 plans remain on track, and we reaffirm our guidance to deliver full-year 2019 adjusted diluted EPS growth of 5% to 7%.” “We continue to believe the evolution of the tobacco industry represents a significant opportunity for Altria. We marked major milestones in our transformation journey this year, including launching IQOS and completing the on! transaction. We believe that, with current adult smoker trends and e-vapor disruption, it’s an opportune time to expand the availability of these options.” “In light of these considerations, we announce a compounded annual adjusted diluted EPS growth objective of 5% to 8% for the years 2020 through 2022. We believe this new growth objective provides us the flexibility to make investments in noncombustible offerings for the long term, generate sustainable income growth in the core tobacco businesses, and return cash to shareholders through a strong dividend. We also expect to maintain our dividend payout ratio target of approximately 80% of adjusted diluted EPS during this period.” As previously announced, a conference call with the investment community and news media will be webcast on October 31, 2019 at 9:00 a.m. -

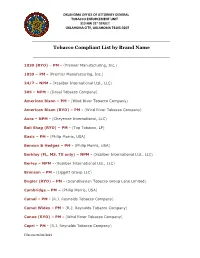

Tobacco Compliant List by Brand Name ______

OKLAHOMA OFFICE OF ATTORNEY GENERAL TOBACCO ENFORCEMENT UNIT 313 NW 21st STREET OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLAHOMA 73105-3207 _____________________________________________________________________________ Tobacco Compliant List by Brand Name _________________________________________ 1839 (RYO) – PM - (Premier Manufacturing, Inc.) 1839 – PM - (Premier Manufacturing, Inc.) 24/7 – NPM - (Xcaliber International Ltd., LLC) 305 – NPM - (Dosal Tobacco Company) American Bison – PM - (Wind River Tobacco Company) American Bison (RYO) – PM - (Wind River Tobacco Company) Aura – NPM - (Cheyenne International, LLC) Bali Shag (RYO) – PM - (Top Tobacco, LP) Basic – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Benson & Hedges – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Berkley (FL, MS, TX only) – NPM - (Xcaliber International Ltd., LLC) Berley – NPM - (Xcaliber International Ltd., LLC) Bronson – PM - (Liggett Group LLC) Bugler (RYO) – PM - (Scandinavian Tobacco Group Lane Limited) Cambridge – PM – (Philip Morris, USA) Camel – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Camel Wides – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Canoe (RYO) – PM - (Wind River Tobacco Company) Capri – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Effective 06/01/2021 Carlton – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Carnival – NPM - (KT&G Corporation) Chesterfield – PM - (Philip Morris, USA) Cheyenne – NPM - (Cheyenne International, LLC) Crowns – PM - (Commonwealth Brands, Inc.) DTC – NPM - (Dosal Tobacco Company) Decade – NPM - (Cheyenne International, LLC) Doral – PM - (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company) Drum (RYO) – PM - (Top Tobacco, LP) Dunhill -

P R O S P E C T

Schedule Application for Additional Shares Listing from Recording date to obtain the Rights : October 8, 2015 : October 22, 2015 Limited Public Offering with Rights Date of Extraordinary General Meeting of Distribution of the Rights Certificate : October 9, 2015 : October 23, 2015 Shareholders (EGMS) Date of Report of EGMS Resolutions Date of Shares Listing in IDX : October 12, 2015 : October 26, 2015 regarding Rights Offering Approval to IDX Announcement Date of EGMS Resolutions : October 12, 2015 Trading Period of Rights : October 26 – 30, 2015 Date of Last Trade of Shares with Rights (Cum Registration, Payment and Exercise : October 26 – 30, 2015 Right) Periods of Rights • Regular and Negotiation Markets : Delivery Period of Shares from October 19, 2015 : November 3, 2015 Exercising the Rights • Cash Market Last Date of Payment for : October 22, 2015 : November 3, 2015 Subscription of Additional Shares Date of Initial Trade of Shares without Rights (ExRight) Allotment Date : November 4, 2015 • Regular and Negotiation Markets : October 20, 2015 Date of Subscription Money Refund : November 6, 2015 S • Cash Market : October 23, 2015 THE FINANCIAL SERVICES AUTHORITY (OTORITAS JASA KEUANGAN OR “OJK”) MAKES NO REPRESENTATION OF APPROVAL OR DISAPPROVAL OF THESE SECURITIES, NOR HAS PASSED UPON THE AUTHENTICITY OR ADEQUACY OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS PROSPECTUS. ANY REPRESENTATION WHICH ARE IN CONTRARY WITH THE ABOVEMENTIONED SHALL BE A VIOLATION OF THE LAW. THE COMPANY AND THE CAPITAL MARKET SUPPORTING PROFESSIONS AND INSTITUTIONS IN THE FRAMEWORK OF THIS LPO ARE FULLY RESPONSIBLE FOR ALL INFORMATION OR MATERIAL FACTS AS WELL AS THE TRUTH OF OPINION PRESENTED IN THIS PROSPECTUS, IN ACCORDANCE WITH ITS RESPECTIVE SCOPE OF WORK BASED ON THE PREVAILING LAWS AND REGULATIONS IN THE TERRITORY OF THE U REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA AND THE CODE OF ETHICS AS WELL AS THE NORMS AND STANDARDS OF EACH PROFESSION.