Anonymous Signatures, Circulating Libraries, Conventionality, and the Production of Gothic Romances Edward Jacobs Old Dominion University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Literature, History, Children's Books And

LONDON 13 DECEMBER 2016 DECEMBER 13 LONDON HISTORY, CHILDREN’S CHILDREN’S HISTORY, ENGLISH LITERATURE, ENGLISH LITERATURE, BOOKS AND BOOKS ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS 13 DECEMBER 2016 L16408 ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS FRONT COVER LOT 67 (DETAIL) BACK COVER LOT 317 THIS PAGE LOT 30 (DETAIL) ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS AUCTION IN LONDON 13 DECEMBER 2016 SALE L16408 SESSION ONE: 10 AM SESSION TWO: 2.30 PM EXHIBITION Friday 9 December 9 am-4.30 pm Saturday 10 December 12 noon-5 pm Sunday 11 December 12 noon-5 pm Monday 12 December 9 am-7 pm 34-35 New Bond Street London, W1A 2AA +44 (0)20 7293 5000 sothebys.com THIS PAGE LOT 101 (DETAIL) SPECIALISTS AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES For further information on lots in this auction please contact any of the specialists listed below. SALE NUMBER SALE ADMINISTRATOR L16408 “BABBITTY” Lukas Baumann [email protected] BIDS DEPARTMENT +44 (0)20 7293 5287 +44 (0)20 7293 5283 fax +44 (0)20 7293 5904 fax +44 (0)20 7293 6255 [email protected] POST SALE SERVICES Kristy Robinson Telephone bid requests should Post Sale Manager Peter Selley Dr. Philip W. Errington be received 24 hours prior FOR PAYMENT, DELIVERY Specialist Specialist to the sale. This service is AND COLLECTION +44 (0)20 7293 5295 +44 (0)20 7293 5302 offered for lots with a low estimate +44 (0)20 7293 5220 [email protected] [email protected] of £2,000 and above. -

Male Novel Reading of the 1790S, Gothic Literature, and Northanger

Male Novel t Reading of the 1790s, :L Gothic Literature, i and Northanger Abbey ALBERT C. SEARS Albert C. Sears is a doctoral candidate in English at Lehigh University. His dissertation investigates the Victorian sensation novel in the literary marketplace. Bookseller records from Timothy Stevens of Cirencester, Gloucestershire, and Thomas Hookham and James Carpenter of London offer new insights into the fiction reading habits of men dur- ing the 1790s.1 Indeed, the Stevens records suggest that Henry Tilney’s emphatic statement in Northanger Abbey (written 1798) that men “‘read nearly as many [novels] as women’” (107) may not be entirely fictional.2 What is more, male patrons of Stevens’s bookshop and library seem to have particularly enjoyed the Gothic as did Tilney, who states: “The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid. I have read all Mrs. Radcliffe’s works, and most of them with great pleasure. The Mysteries of Udolpho, when I had once begun it, I could not lay down again;—I remember finishing it in two days—my hair standing on end the whole time.” (106) However, while Austen’s depiction of male novel reading may be accurate for Gloucestershire, the Hookham records yield little evi- dence that the majority of men in fashionable London enjoyed novels as much as Tilney. 106 PERSUASIONS No. 21 The Stevens records, which extend from 1780 to 1806, do show that men borrowed and bought more fiction than women during the last decade of the eighteenth century. During the 1790s, the shop had approximately seventy male patrons (includ- ing book clubs) who borrowed and/or purchased fiction. -

Books, Maps and Photographs

BOOKS, MAPS AND PHOTOGRAPHS Tuesday 25 November 2014 Oxford BOOKS, MAPS AND PHOTOGRAPHS | Oxford | Tuesday 25 November 2014 | Tuesday | Oxford 21832 BOOKS, MAPS AND PHOTOGRAPHS Tuesday 25 November 2014 at 11.00 Oxford BONHAMS Live online bidding is CUstomER SErvICES Important INFormatION Banbury Road available for this sale Monday to Friday 8.30 to 18.00 The United States Shipton on Cherwell Please email bids@bonhams. +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Government has banned the Kidlington com with ‘live bidding’ in the import of ivory into the USA. Oxford OX5 1JH subject line 48 hours before the Please see page 2 for bidder Lots containing ivory are bonhams.com auction to register for this information including after-sale indicated by the symbol Ф service collection and shipment printed beside the lot number VIEWING in this catalogue. Saturday 22 November 09.00 to Please note we only accept SHIPPING AND COLLECTIONS 12.00 telephone bids for lots with a Oxford Monday 24 November 09.00 to low estimate of £500 or Georgina Roberts 16.30 higher. Tuesday 25 November limited +44 (0) 1865 853 647 [email protected] viewing 09.00 to 10.30 EnQUIRIES Oxford BIDS London John Walwyn-Jones +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Jennifer Ebrey Georgina Roberts +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7393 3841 Sian Wainwright To bid via the internet please [email protected] +44 (0) 1865 853 646 visit bonhams.com +44 (0) 1865 853 647 Please see back of catalogue +44 (0) 1865 853 648 Please note that bids should be for important notice to +44 (0) 1865 372 722 fax submitted no later than 24 hours bidders prior to the sale. -

Ann Radcliffe, Mary Ann Radcliffe and the Minerva Author Joellen• Delucia

R OMANTICT EXTUALITIES LITERATURE AND PRINT CULTURE, 1780–1840 • ISSN 1748-0116 ◆ ISSUE 23 ◆ SUMMER 2020 ◆ SPECIAL ISSUE : THE MINERVA PRESS AND THE LITERARY MARKETPLACE ◆ www.romtext.org.uk ◆ CARDIFF UNIVERSITY PRESS ◆ 2 romantic textualities 23 Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840, 23 (Summer 2020) Available online at <www.romtext.org.uk/>; archive of record at <https://publications.cardiffuniversitypress.org/index.php/RomText>. Journal DOI: 10.18573/issn.1748-0116 ◆ Issue DOI: 10.18573/romtext.i23 Romantic Textualities is an open access journal, which means that all content is available without charge to the user or his/her institution. You are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from either the publisher or the author. Unless otherwise noted, the material contained in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 (cc by-nc-nd) Interna- tional License. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ for more information. Origi- nal copyright remains with the contributing author and a citation should be made when the article is quoted, used or referred to in another work. C b n d Romantic Textualities is an imprint of Cardiff University Press, an innovative open-access publisher of academic research, where ‘open-access’ means free for both readers and writers. Find out more about the press at cardiffuniversitypress.org. Editors: Anthony Mandal, -

Cata 208 Text.Indd

Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London www.jarndyce.co.uk WC1B 3PA VAT.No.: GB 524 0890 57 CATALOGUE CCVIII SPRING 2014 THE ROMANTICS: PART II. D-R De Quincey, Hunt, Keats, Lamb, Rogers, &c. Catalogue: Joshua Clayton Production: Ed Lake & Carol Murphy All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items on this catalogue marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (20%) to customers within the EU. A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. Email address for this catalogue is [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE, price £5.00 each include: The Romantics: Part I. A-C; Books from the Library of Geoffrey & Kathleen Tillotson; The Shop Catalogue; Books & Pamphlets 1576-1827; Catalogues 205 & 200: Jarndyce Miscellanies; Dickens & His Circle; The Dickens Catalogue; The Library of a Dickensian; Street Literature: III Songsters, Reference Sources, Lottery Tickets & ‘Puffs’; Social Science, Part I: Politics & Philosophy; Part II: Economics & Social History; The Social History of London; Women II-IV: Women Writers A-Z. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: The Romantics: Part III. S-Z; 18th & 19th Century Books & Pamphlets; Conduct & Education. PLEASE REMEMBER: If you have books to sell, please get in touch with Brian Lake at Jarndyce. Valuations for insurance or probate can be undertaken anywhere, by arrangement. -

Reading Between the Minds: Intersubjectivity and The

READING BETWEEN THE MINDS: INTERSUBJECTIVITY AND THE EMERGENCE OF MODERNISM FROM ROBERT BROWNING TO HENRY JAMES by Jennie Hann A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May 2017 © 2017 Jennie Hann All Rights Reserved DEDICATION For my parents, Alan and Mary Kay Hann And in memory of Shaughnessy ii Is the creature too imperfect, say? Would you mend it And so end it? Since not all addition perfects aye! Or is it of its kind, perhaps, Just perfection— Whence, rejection Of a grace not to its mind, perhaps? Shall we burn up, tread that face at once Into tinder, And so hinder Sparks from kindling all the place at once? —Robert Browning, “A Pretty Woman” (1855) Really, universally, relations stop nowhere, and the exquisite problem of the artist is eternally but to draw, by a geometry of his own, the circle within which they shall happily appear to do so. He is in the perpetual predicament that the continuity of things is the whole matter, for him, of comedy and tragedy; that this continuity is never, by the space of an instant or an inch, broken, and that, to do anything at all, he has at once intensely to consult and to ignore it. All of which will perhaps pass but for a supersubtle way of pointing the plain moral that a young embroiderer of the canvas of life soon began to work in terror, fairly, of the vast expanse of that surface, of the boundless number of its distinct perforations . -

A Previously Unremarked Circulating Library

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Faculty Publications English 1995 A Previously Unremarked Circulating Library: John Roson and the Role of Circulating-Library Proprietors as Publishers in Eighteenth-Century Britain Edward Jacobs Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_fac_pubs Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Repository Citation Jacobs, Edward, "A Previously Unremarked Circulating Library: John Roson and the Role of Circulating-Library Proprietors as Publishers in Eighteenth-Century Britain" (1995). English Faculty Publications. 24. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_fac_pubs/24 Original Publication Citation Jacobs, E. (1995). A previously unremarked circulating library: John Roson and the role of circulating-library proprietors as publishers in eighteenth-century Britain. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 89(1), 61-71. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bibliographical Society of America A Previously Unremarked Circulating Library: John Roson and the Role of Circulating- Library Proprietors as Publishers in Eighteenth-Century Britain Authors(s): Edward Jacobs Source: The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, Vol. 89, No. 1 (MARCH 1995), pp. 61-71 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Bibliographical Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24304635 Accessed: 25-03-2016 18:12 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24304635?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. -

Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 11 | 2015 Expressions of Environment in Euroamerican Culture / Antique Bodies in Nineteenth Century British Literature and Culture Dale Townshend, Angela Wright (eds), Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic Laurence Talairach-Vielmas Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/7149 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.7149 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Laurence Talairach-Vielmas, “Dale Townshend, Angela Wright (eds), Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic ”, Miranda [Online], 11 | 2015, Online since 22 July 2015, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/7149 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.7149 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Dale Townshend, Angela Wright (eds), Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic 1 Dale Townshend, Angela Wright (eds), Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic Laurence Talairach-Vielmas REFERENCES Dale Townshend, Angela Wright (eds), Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 257 p, ISBN 978–1–107–03283–5 1 1764 marked both the publication of the first Gothic story, Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), and the birth of one of the most popular Gothic writers of the romantic period—Ann Radcliffe. 250 years later, Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic, edited by Dale Towshend and Angela Wright, freshly re-examines Radcliffe’s work, looking at the impact and reception of her œuvre and its relationship to the Romantic literary and cultural contexts. -

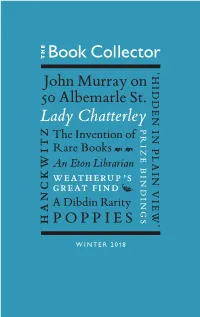

The-Book-Collector-Example-2018-04.Pdf

641 blackwell’s blackwell’s rare books rare48-51 Broad books Street, 48-51 Broad Street, 48-51Oxford, Broad OX1 Street, 3BQ Oxford, OX1 3BQ CataloguesOxford, OX1 on 3BQrequest Catalogues on request CataloguesGeneral and subject on catalogues request issued GeneralRecent and subject subject catalogues catalogues include issued General and subject catalogues issued blackwellRecentModernisms, subject catalogues Sciences, include ’s Recent subject catalogues include blackwellandModernisms, Greek & Latin Sciences, Classics ’s rareandModernisms, Greek &books Latin Sciences, Classics rareand Greek &books Latin Classics 48-51 Broad Street, 48-51Oxford, Broad OX1 Street, 3BQ Oxford, OX1 3BQ Catalogues on request Catalogues on request General and subject catalogues issued GeneralRecent and subject subject catalogues catalogues include issued RecentModernisms, subject catalogues Sciences, include andModernisms, Greek & Latin Sciences, Classics and Greek & Latin Classics 641 APPRAISERS APPRAISERS CONSULTANTS CONSULTANTS 642 Luis de Lucena, Repetición de amores, y Arte de ajedres, first edition of the earliest extant manual of modern chess, Salamanca, circa 1496-97. Sold March 2018 for $68,750. Accepting Consignments for Autumn 2018 Auctions Early Printing • Medicine & Science • Travel & Exploration • Art & Architecture 19th & 20th Century Literature • Private Press & Illustrated Americana & African Americana • Autographs • Maps & Atlases [email protected] 104 East 25th Street New York, NY 10010 212 254 4710 SWANNGALLERIES.COM 643 Heribert Tenschert -

Bibliotecas Circulantes Na Revolução Industrial Inglesa: a Inclusão Social Da Mulher Na Economia Do Livro

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO ESTADO DO RIO DE JANEIRO CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS E SOCIAIS ESCOLA DE BIBLIOTECONOMIA AMANDA SALOMÃO BIBLIOTECAS CIRCULANTES NA REVOLUÇÃO INDUSTRIAL INGLESA: INCLUSÃO SOCIAL DA MULHER NA ECONOMIA DO LIVRO Rio de Janeiro 2017 AMANDA SALOMÃO BIBLIOTECAS CIRCULANTES NA REVOLUÇÃO INDUSTRIAL INGLESA: INCLUSÃO SOCIAL DA MULHER NA ECONOMIA DO LIVRO Trabalho de conclusão de curso apresentado à Escola de Biblioteconomia da Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro como pré- requisito para a obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Biblioteconomia. Orientação: Prof. Dr. Eduardo da Silva Alentejo Rio de Janeiro 2017 SALOMÃO, Amanda. S173c Bibliotecas circulantes na Revolução Industrial inglesa: a inclusão social da mulher na economia do livro. / Amanda Salomão. - 2017. 106 f.: il. color. ; 30 cm. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Graduação em Biblioteconomia) – Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2017. Orientador: Professor Dr. Eduardo da Silva Alentejo. 1. Bibliotecas circulantes. 2. Inclusão social da mulher. 3. Escrita feminina. 4. Economia do livro. 5. Romance inglês. I. ALENTEJO, Eduardo da Silva. II. Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. III. Título. CDD: 025 CDU: xxxxx CDU:xxxxxx AMANDA SALOMÃO BIBLIOTECAS CIRCULANTES NA REVOLUÇÃO INDUSTRIAL INGLESA: INCLUSÃO SOCIAL DA MULHER NA ECONOMIA DO LIVRO Trabalho de conclusão de curso apresentado à Escola de Biblioteconomia da Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, como pré-requisito para a obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Biblioteconomia. Rio de Janeiro, ____ de ____________ de 2017. Banca Examinadora _________________________________________________ Professor Dr. Eduardo da Silva Alentejo (orientador) Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro _________________________________________________ Professor MSc. -

CALIFORNIA 2019 Pasadena Convention Center | February 1–2 | Stand B-318 Oakland Marriott City Center | February 8–10 | Stand 716

CALIFORNIA 2019 Pasadena Convention Center | February 1–2 | Stand B-318 Oakland Marriott City Center | February 8–10 | Stand 716 Ashendene Press Dante Austen, Pride and Prejudice ANSON, George. A Voyage Round the World. London: printed [AUSTEN, Jane.] Pride and Prejudice. London: for T. Egerton, for the Author; by John and Paul Knapton, 1748 1813 first edition, subscriber’s copy, in the most desirable original first edition, rare in a contemporary binding. 3 vols., 12mo, con- quarto format, in contemporary calf. A wide-margined copy. temporary red half roan gilt. A very attractive copy. $6,250 [124562] $125,000 [130995] (ASHENDENE PRESS.) DANTE ALIGHIERI. [La Divina [AUSTEN, Jane.] Mansfield Park. London: for T. Egerton, 1814 Commedia.] Chelsea: Ashendene Press, 1902–5 first edition. 3 vols., 12mo, contemporary marbled calf expertly first ashendene press edition, exceptionally uncommon com- rebacked to style. A very good set. plete. Inferno one of 135 copies, Purgatorio and Paradiso each one of 150. $20,000 [130061] 3 vols., small 4to, original limp vellum, with the silk ties. $30,000 [130817] Peter Harrington, 100 Fulham Road, London, SW3 6HS, UK · Tel +44 20 7591 0220 · [email protected] Brontë (BORGES, Jorge Luis.) Antologia Poetica Argentina. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, December 1941 Blake first edition, borges’s own copy of this anthology of Argentine poetry, signed by him in the year of publication. 8vo, original wrap- BECKETT, Samuel. En attendant Godot. Paris: Les Éditions de pers; the Guillermo de Torre copy. Minuit, 1952 $6,000 [130206] first edition, one of 35 copies on vélin supérieur. 8vo, original white wrappers, in the original glassine. -

Rare Books & Manuscripts

Sale 479 Thursday, May 10, 2012 11:00 AM Rare Books & Manuscripts: The Library of Michael Killigrew desTombe (with additions) Auction Preview Tuesday May 8, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, May 9, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, May 10, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material.