TESE Ralf Tarciso Silva Cordeiro.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Precious Corals (Coralliidae) from North-Western Atlantic Seamounts A

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Marine Sciences Faculty Scholarship School of Marine Sciences 3-1-2011 Precious Corals (Coralliidae) from North-Western Atlantic Seamounts A. Simpson Les Watling University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/sms_facpub Repository Citation Simpson, A. and Watling, Les, "Precious Corals (Coralliidae) from North-Western Atlantic Seamounts" (2011). Marine Sciences Faculty Scholarship. 97. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/sms_facpub/97 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marine Sciences Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2011, 91(2), 369–382. # Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2010 doi:10.1017/S002531541000086X Precious corals (Coralliidae) from north-western Atlantic Seamounts anne simpson1 and les watling1,2 1Darling Marine Center, University of Maine, Walpole, ME 04573, USA, 2Department of Zoology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA Two new species belonging to the precious coral genus Corallium were collected during a series of exploratory cruises to the New England and Corner Rise Seamounts in 2003–2005. One red species, Corallium bathyrubrum sp. nov., and one white species, C. bayeri sp. nov., are described. Corallium bathyrubrum is the first red Corallium to be reported from the western Atlantic. An additional species, C. niobe Bayer, 1964 originally described from the Straits of Florida, was also collected and its description augmented. -

MARINE FAUNA and FLORA of BERMUDA a Systematic Guide to the Identification of Marine Organisms

MARINE FAUNA AND FLORA OF BERMUDA A Systematic Guide to the Identification of Marine Organisms Edited by WOLFGANG STERRER Bermuda Biological Station St. George's, Bermuda in cooperation with Christiane Schoepfer-Sterrer and 63 text contributors A Wiley-Interscience Publication JOHN WILEY & SONS New York Chichester Brisbane Toronto Singapore ANTHOZOA 159 sucker) on the exumbrella. Color vari many Actiniaria and Ceriantharia can able, mostly greenish gray-blue, the move if exposed to unfavorable condi greenish color due to zooxanthellae tions. Actiniaria can creep along on their embedded in the mesoglea. Polyp pedal discs at 8-10 cm/hr, pull themselves slender; strobilation of the monodisc by their tentacles, move by peristalsis type. Medusae are found, upside through loose sediment, float in currents, down and usually in large congrega and even swim by coordinated tentacular tions, on the muddy bottoms of in motion. shore bays and ponds. Both subclasses are represented in Ber W. STERRER muda. Because the orders are so diverse morphologically, they are often discussed separately. In some classifications the an Class Anthozoa (Corals, anemones) thozoan orders are grouped into 3 (not the 2 considered here) subclasses, splitting off CHARACTERISTICS: Exclusively polypoid, sol the Ceriantharia and Antipatharia into a itary or colonial eNIDARIA. Oral end ex separate subclass, the Ceriantipatharia. panded into oral disc which bears the mouth and Corallimorpharia are sometimes consid one or more rings of hollow tentacles. ered a suborder of Scleractinia. Approxi Stomodeum well developed, often with 1 or 2 mately 6,500 species of Anthozoa are siphonoglyphs. Gastrovascular cavity compart known. Of 93 species reported from Ber mentalized by radially arranged mesenteries. -

Coelenterata: Anthozoa), with Diagnoses of New Taxa

PROC. BIOL. SOC. WASH. 94(3), 1981, pp. 902-947 KEY TO THE GENERA OF OCTOCORALLIA EXCLUSIVE OF PENNATULACEA (COELENTERATA: ANTHOZOA), WITH DIAGNOSES OF NEW TAXA Frederick M. Bayer Abstract.—A serial key to the genera of Octocorallia exclusive of the Pennatulacea is presented. New taxa introduced are Olindagorgia, new genus for Pseudopterogorgia marcgravii Bayer; Nicaule, new genus for N. crucifera, new species; and Lytreia, new genus for Thesea plana Deich- mann. Ideogorgia is proposed as a replacement ñame for Dendrogorgia Simpson, 1910, not Duchassaing, 1870, and Helicogorgia for Hicksonella Simpson, December 1910, not Nutting, May 1910. A revised classification is provided. Introduction The key presented here was an essential outgrowth of work on a general revisión of the octocoral fauna of the western part of the Atlantic Ocean. The far-reaching zoogeographical affinities of this fauna made it impossible in the course of this study to ignore genera from any part of the world, and it soon became clear that many of them require redefinition according to modern taxonomic standards. Therefore, the type-species of as many genera as possible have been examined, often on the basis of original type material, and a fully illustrated generic revisión is in course of preparation as an essential first stage in the redescription of western Atlantic species. The key prepared to accompany this generic review has now reached a stage that would benefit from a broader and more objective testing under practical conditions than is possible in one laboratory. For this reason, and in order to make the results of this long-term study available, even in provisional form, not only to specialists but also to the growing number of ecologists, biochemists, and physiologists interested in octocorals, the key is now pre- sented in condensed form with minimal illustration. -

Preliminary Report on the Octocorals (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Octocorallia) from the Ogasawara Islands

国立科博専報,(52), pp. 65–94 , 2018 年 3 月 28 日 Mem. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci., Tokyo, (52), pp. 65–94, March 28, 2018 Preliminary Report on the Octocorals (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Octocorallia) from the Ogasawara Islands Yukimitsu Imahara1* and Hiroshi Namikawa2 1Wakayama Laboratory, Biological Institute on Kuroshio, 300–11 Kire, Wakayama, Wakayama 640–0351, Japan *E-mail: [email protected] 2Showa Memorial Institute, National Museum of Nature and Science, 4–1–1 Amakubo, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305–0005, Japan Abstract. Approximately 400 octocoral specimens were collected from the Ogasawara Islands by SCUBA diving during 2013–2016 and by dredging surveys by the R/V Koyo of the Tokyo Met- ropolitan Ogasawara Fisheries Center in 2014 as part of the project “Biological Properties of Bio- diversity Hotspots in Japan” at the National Museum of Nature and Science. Here we report on 52 lots of these octocoral specimens that have been identified to 42 species thus far. The specimens include seven species of three genera in two families of Stolonifera, 25 species of ten genera in two families of Alcyoniina, one species of Scleraxonia, and nine species of four genera in three families of Pennatulacea. Among them, three species of Stolonifera: Clavularia cf. durum Hick- son, C. cf. margaritiferae Thomson & Henderson and C. cf. repens Thomson & Henderson, and five species of Alcyoniina: Lobophytum variatum Tixier-Durivault, L. cf. mirabile Tixier- Durivault, Lohowia koosi Alderslade, Sarcophyton cf. boletiforme Tixier-Durivault and Sinularia linnei Ofwegen, are new to Japan. In particular, Lohowia koosi is the first discovery since the orig- inal description from the east coast of Australia. -

Guide to the Identification of Precious and Semi-Precious Corals in Commercial Trade

'l'llA FFIC YvALE ,.._,..---...- guide to the identification of precious and semi-precious corals in commercial trade Ernest W.T. Cooper, Susan J. Torntore, Angela S.M. Leung, Tanya Shadbolt and Carolyn Dawe September 2011 © 2011 World Wildlife Fund and TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9693730-3-2 Reproduction and distribution for resale by any means photographic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any parts of this book, illustrations or texts is prohibited without prior written consent from World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Reproduction for CITES enforcement or educational and other non-commercial purposes by CITES Authorities and the CITES Secretariat is authorized without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit WWF and TRAFFIC North America. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The designation of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF, TRAFFIC, or IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint program of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Cooper, E.W.T., Torntore, S.J., Leung, A.S.M, Shadbolt, T. and Dawe, C. -

New Record of Melithaea Retifera (Lamarck, 1816) from Andaman and Nicobar Island, India

Indian Journal of Geo Marine Sciences Vol. 48 (10), October 2019, pp. 1516-1520 New record of Melithaea retifera (Lamarck, 1816) from Andaman and Nicobar Island, India J. S. Yogesh Kumar1*, S. Geetha2, C. Raghunathan3 & R. Sornaraj2 1Marine Aquarium and Regional Centre, Zoological Survey of India, (MoEFCC), Government of India, Digha, West Bengal, India. 2Research Department of Zoology, Kamaraj College (Manonmaniam Sundaranar University), Thoothukudi, Tamil Nadu, India. 3Zoological Survey of India (MoEFCC), Government of India, M Block, New Alipore, Kolkata, West Bengal, India. *[E-mail: [email protected]] Received 25 April 2018; revised 04 June 2018 Alcyoniidae octocorals are represented by 405 species in India of which 154 are from Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Surveys conducted in Havelock Island, South Andaman and Shark Island, North Andaman revealed the occurrence of Melithaea retifera and is reported herein as a new distributional record to Andaman and Nicobar Islands. This species is characterised by the clubs of the coenenchyme of the node and internodes and looks like a flower-bud. The structural variations and length of sclerites in the samples are also reported in this manuscript. [Keywords: Octocoral; Soft coral; Melithaeidae; Melithaea retifera; Havelock Island; Shark Island; Andaman and Nicobar; India.] Introduction identification15. The axis of Melithaeidae has short The Alcyonacea are sedentary, colonial growth and long internodes; those sclerites are short, smooth, forms belonging to the subclass Octocorallia. The rod-shaped9. Recently the family Melithaeidae was subclass Octocorallia belongs to Class Anthozoa, recognized18 based on the DNA molecular Phylum Cnidaria and is commonly called as soft phylogenetic relationship and synonymised Acabaria, corals (Alcyonacea), seafans (Gorgonacea), blue Clathraria, Melithaea, Mopsella, Wrightella under corals (Helioporacea), sea pens and sea pencil this family. -

![Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9917/genetic-divergence-and-polyphyly-in-the-octocoral-genus-swiftia-cnidaria-octocorallia-including-a-species-impacted-by-the-dwh-oil-spill-739917.webp)

Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill

diversity Article Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill Janessy Frometa 1,2,* , Peter J. Etnoyer 2, Andrea M. Quattrini 3, Santiago Herrera 4 and Thomas W. Greig 2 1 CSS Dynamac, Inc., 10301 Democracy Lane, Suite 300, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA 2 Hollings Marine Laboratory, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Sciences, National Ocean Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 331 Fort Johnson Rd, Charleston, SC 29412, USA; [email protected] (P.J.E.); [email protected] (T.W.G.) 3 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 10th and Constitution Ave NW, Washington, DC 20560, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Biological Sciences, Lehigh University, 111 Research Dr, Bethlehem, PA 18015, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) are recognized around the world as diverse and ecologically important habitats. In the northern Gulf of Mexico (GoMx), MCEs are rocky reefs with abundant black corals and octocorals, including the species Swiftia exserta. Surveys following the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill in 2010 revealed significant injury to these and other species, the restoration of which requires an in-depth understanding of the biology, ecology, and genetic diversity of each species. To support a larger population connectivity study of impacted octocorals in the Citation: Frometa, J.; Etnoyer, P.J.; GoMx, this study combined sequences of mtMutS and nuclear 28S rDNA to confirm the identity Quattrini, A.M.; Herrera, S.; Greig, Swiftia T.W. -

Cnidarian Immunity and the Repertoire of Defense Mechanisms in Anthozoans

biology Review Cnidarian Immunity and the Repertoire of Defense Mechanisms in Anthozoans Maria Giovanna Parisi 1,* , Daniela Parrinello 1, Loredana Stabili 2 and Matteo Cammarata 1,* 1 Department of Earth and Marine Sciences, University of Palermo, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences and Technologies, University of Salento, 73100 Lecce, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.G.P.); [email protected] (M.C.) Received: 10 August 2020; Accepted: 4 September 2020; Published: 11 September 2020 Abstract: Anthozoa is the most specious class of the phylum Cnidaria that is phylogenetically basal within the Metazoa. It is an interesting group for studying the evolution of mutualisms and immunity, for despite their morphological simplicity, Anthozoans are unexpectedly immunologically complex, with large genomes and gene families similar to those of the Bilateria. Evidence indicates that the Anthozoan innate immune system is not only involved in the disruption of harmful microorganisms, but is also crucial in structuring tissue-associated microbial communities that are essential components of the cnidarian holobiont and useful to the animal’s health for several functions including metabolism, immune defense, development, and behavior. Here, we report on the current state of the art of Anthozoan immunity. Like other invertebrates, Anthozoans possess immune mechanisms based on self/non-self-recognition. Although lacking adaptive immunity, they use a diverse repertoire of immune receptor signaling pathways (PRRs) to recognize a broad array of conserved microorganism-associated molecular patterns (MAMP). The intracellular signaling cascades lead to gene transcription up to endpoints of release of molecules that kill the pathogens, defend the self by maintaining homeostasis, and modulate the wound repair process. -

Pontificia Universidad Católica De Valparaíso Facultad De Recursos Naturales Escuela De Ciencias Del Mar Valparaíso – Chile

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Facultad de Recursos Naturales Escuela de Ciencias del Mar Valparaíso – Chile INFORME FINAL CARACTERIZACION DEL FONDO MARINO ENTRE LA III Y X REGIONES (Proyecto FIP Nº 2005-61) Valparaíso, octubre de 2007 i Título: “Caracterización del fondo marino entre la III y X Regiones” Proyecto FIP Nº 2005-61 Requirente: Fondo de Investigación Pesquera Contraparte: Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Facultad de Recursos Naturales Unidad Ejecutora: Escuela de Ciencias del Mar Avda. Altamirano 1480 Casilla 1020 Valparaíso Investigador Responsable: Teófilo Melo Fuentes Escuela de Ciencias del Mar Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Fono : 56-32-274264 Fax : 56-32-274206 E-mail: [email protected] Subcontrato: Universidad Católica del Norte – UCN Universidad Austral de Chile – UACH ii EQUIPO DE TRABAJO INVESTIGADORES INSTITUCION AREA DE TRABAJO Teófilo Melo F. PUCV Tecnología pesquera Juan Díaz N. PUCV Geofísica marina José I. Sepúlveda V. PUCV Oceanografía biológica Nelson Silva S. PUCV Oceanografía física y química Javier Sellanes L. UCN Comunidades benónicas Praxedes Muñoz UCN Oceanografía geo-química Julio Lamilla G. UACH Ictiología de tiburones, rayas y quimeras Alejandro Bravo UACH Corales Rodolfo Vögler Cons. Independiente Comunidades y relaciones tróficas Germán Pequeño1 UACH Ictiología CO-INVESTIGADORES INSTITUCION AREA DE TRABAJO Y COLABORADORES Carlos Hurtado F. PUCV Coordinación general Dante Queirolo P. PUCV Intensidad y distribución del esfuerzo de pesca Patricia Rojas Z.2 PUCV Análisis de contenido estomacal Yenny Guerrero A. PUCV Oceanografía física y química Erick Gaete A. PUCV Jefe de crucero y filmaciones submarinas Ivonne Montenegro U. PUCV Manejo de bases de datos Roberto Escobar H. PUCV Toma de datos en cruceros Víctor Zamora A. -

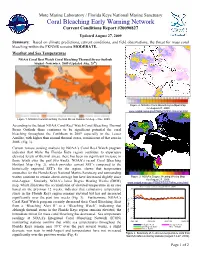

Coral Bleaching Early Warning Network Current Conditions Report #20090827

Mote Marine Laboratory / Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Coral Bleaching Early Warning Network Current Conditions Report #20090827 Updated August 27, 2009 Summary: Based on climate predictions, current conditions, and field observations, the threat for mass coral bleaching within the FKNMS remains MODERATE. Weather and Sea Temperatures NOAA Coral Reef Watch Coral Bleaching Thermal Stress Outlook August -November, 2009 (Updated Aug. 25th) Figure 2. NOAA’s Coral Bleaching HotSpot Map for August 27, 2009. www.osdpd.noaa.gov/PSB/EPS/SST/climohot.html Figure 1. NOAA’s Coral Bleaching Thermal Stress Outlook for Aug. – Nov. 2009. According to the latest NOAA Coral Reef Watch Coral Bleaching Thermal Stress Outlook there continues to be significant potential for coral bleaching throughout the Caribbean in 2009 especially in the Lesser Antilles, with higher than normal thermal stress, reminiscent of that seen in 2005. (Fig. 1). Current remote sensing analysis by NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch program indicates that while the Florida Keys region continues to experience elevated levels of thermal stress, there has been no significant increase in those levels over the past two weeks. NOAA’s recent Coral Bleaching HotSpot Map (Fig. 2), which provides current SST’s compared to the historically expected SST’s for the region, shows that temperature anomalies for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and surrounding waters continue to remain above-average but have decreased slightly since Figure 3. NOAA’s Degree Heating Weeks Map for August 27, 2009. mid-August. Similarly, NOAA’s latest Degree Heating Weeks (DHW) www.osdpd.noaa.gov/PSB/EPS/SST/dhw_retro.html map, which illustrates the accumulation of elevated temperature in an area Water Temperatures (August 13-27, 2009) based on the previous 12 weeks, indicates that cumulative temperature 35 stress in the Florida Keys region remains elevated but has not increased significantly over the past two weeks (Fig. -

The Aquaculture of Live Rock, Live Sand, Coral and Associated Products

AQUACULTURE OF LIVE ROCKS, LIVE SAND, CORAL AND ASSOCIATED PRODUCTS A DISCUSSION AND DRAFT POLICY PAPER FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PAPER NO. 196 Department of Fisheries 168 St. Georges Terrace Perth WA 6000 April 2006 ISSN 0819-4327 The Aquaculture of Live Rock, Live Sand, Coral and Associated Products A Discussion and Draft Policy Paper Project Managed by Andrew Beer April 2006 Fisheries Management Paper No. 196 ISSN 0819-4327 Fisheries Management Paper No. 196 CONTENTS OPPORTUNITY FOR PUBLIC COMMENT...............................................................IV DISCLAIMER V ACKNOWLEDGEMENT..................................................................................................V SECTION 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & PROPOSED POLICY OPTIONS ....... 1 SECTION 2 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................... 5 2.1 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................. 5 2.2 OBJECTIVES................................................................................................. 5 2.3 WHY LIVE ROCK, SAND AND CORAL AQUACULTURE? ............................... 6 2.4 MARKET...................................................................................................... 6 SECTION 3 THE TAXONOMY AND BIOLOGY OF LIVE ROCK, SAND AND CORAL ..................................................................................................... 9 3.1 LIVE ROCK ................................................................................................. -

Target Substrata

TARGET SUBSTRATA OVERVIEW CORALS AND THEIR RELATIVES STONY HEXACORALS OTHER HEXACORALS OCTOCORALS HYDROZOANS Acropora Sea Anemones Soft Corals Fire Coral Non-Acropora Zoanthids Sea Fans Lace Coral Black Coral Blue Coral Hydroids Corallimorpharians Organ Pipe OTHER SUBSTRATA Sponge Macroalgae Dead Coral Rock Coralline Algae Dead Coral With Algae Rubble Algal Assemblage Turf Algae Sand Silt CORALS AND THEIR RELATIVES STONY CORALS ACROPORA Phylum Cnidaria | Class Anthozoa | Sub-Class Hexacorallia | Order Scleractinia (Hard Corals) | Family Acroporidae | Genus Acropora Acropora is one genus within the family of Acroporidae; Generally, the species are characterized by the presence of an axial (terminal) corallite (skeleton of an individual polyp) at the branch tips surrounded by radial corallites; The name Acropora is derived from the Greek “akron” which means summit. Acropora Branching Barefoot Conservation | TARGET SUBSTRATA | July 2016 1 Acropora Bottlebrush Acropora Digitate Acropora Tabulate Barefoot Conservation | TARGET SUBSTRATA | July 2016 2 Acropora Submassive Acropora Encrusting Non-Acropora Phylum Cnidaria | Class Anthozoa | Sub-Class Hexacorallia | Order Scleractinia (Hard Corals) | Family Acroporidae Coral Branching Barefoot Conservation | TARGET SUBSTRATA | July 2016 3 (continued) Coral Branching Coral Massive Barefoot Conservation | TARGET SUBSTRATA | July 2016 4 Coral Encrusting Coral Foliose Coral Submassive Barefoot Conservation | TARGET SUBSTRATA | July 2016 5 (continued) Coral Submassive Coral Mushroom Barefoot Conservation