John Adams American Composer Born: February 15, 1947, Worcester, Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Atomic

What to Expect from doctor atomic Opera has alwayS dealt with larger-than-life Emotions and scenarios. But in recent decades, composers have used the power of THE WORK DOCTOR ATOMIC opera to investigate society and ethical responsibility on a grander scale. Music by John Adams With one of the first American operas of the 21st century, composer John Adams took up just such an investigation. His Doctor Atomic explores a Libretto by Peter Sellars, adapted from original sources momentous episode in modern history: the invention and detonation of First performed on October 1, 2005, the first atomic bomb. The opera centers on Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, in San Francisco the brilliant physicist who oversaw the Manhattan Project, the govern- ment project to develop atomic weaponry. Scientists and soldiers were New PRODUCTION secretly stationed in Los Alamos, New Mexico, for the duration of World Alan Gilbert, Conductor War II; Doctor Atomic focuses on the days and hours leading up to the first Penny Woolcock, Production test of the bomb on July 16, 1945. In his memoir Hallelujah Junction, the American composer writes, “The Julian Crouch, Set Designer manipulation of the atom, the unleashing of that formerly inaccessible Catherine Zuber, Costume Designer source of densely concentrated energy, was the great mythological tale Brian MacDevitt, Lighting Designer of our time.” As with all mythological tales, this one has a complex and Andrew Dawson, Choreographer fascinating hero at its center. Not just a scientist, Oppenheimer was a Leo Warner and Mark Grimmer for Fifty supremely cultured man of literature, music, and art. He was conflicted Nine Productions, Video Designers about his creation and exquisitely aware of the potential for devastation Mark Grey, Sound Designer he had a hand in designing. -

2020-2021 BNY Mellon Grand Classics Renewal Brochure

SE THE 2020-2021 SEASON! A ASON O BENEFITS F FIRSTS! FLEXIBLE TICKET PRIORITY SEATING DISTRICT DISCOUNTS RENEW A new piano, 10 artist debuts, significant EXCHANGE Season ticket holders have priority Pittsburgh Symphony subscribers TODAY! Pittsburgh firsts, world premieres, PSO Exchange your subscription tickets over the general public on all receive a discount to select premieres and new musical voices. for any other concert within the seating within the BNY Mellon Pittsburgh Ballet, Pittsburgh CLO, 2020-2021 BNY Mellon Grand Grand Classics season. Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, Pittsburgh Classics season. Season ticket Opera and Pittsburgh Public CLICK OUTSTANDING holders can make exchanges up EXCLUSIVE PRE-SALE Theater events, as well as discounts PittsburghSymphony.org/Renew STARS OF to one hour prior to the concert. OPPORTUNITIES to local restaurants. THE STAGE Ticket exchanges made online are As a ticket holder, you will receive exclusive pre-sale opportunities to RESERVED PARKING Performances by Emanuel free of fees. special concerts before the general Season ticket holders have the first CALL Ax, Rudolf Buchbinder, DEDICATED public on-sale date. opportunity to purchase pre-paid +HLQ]+DOO%R[2IƓFH Thibaudet Hélène Grimaud, Gil Shaham, th PATRON SERVICES guaranteed parking in the 6 and 412.392.4900 Christian Tetzlaff, Matthias REPRESENTATIVE GREAT SAVINGS Penn garage across the street from Toll-free: 800.743.8560 Goerne, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Each season ticket holder has Save on the concerts within your Heinz Hall for just $12 per concert. Yefim Bronfman, and Yo-Yo Ma! a designated Patron Services season ticket package. Plus, save After the renewal deadline parking Representative (PSR) to personally 15% on additional ticket purchases prices increase to $15. -

Program Notes: Inspiration & Impact

CABRILLO FESTIVAL Program Notes: Inspiration & Impact Lola Montez Does the and she glides from the stage of sensory and expressive overload. Spider Dance (2016) overwhelmed with applause, At its premiere in March of 2012, the first third and smashed spiders, John Adams of the piece was largely a trope on the Opus (b. 1947) and radiant with parti-colored skirts, [World Premiere] 131 C# minor quartet’s scherzo and suffered smiles, graces, cobwebs and glory. from just this problem. After a moody opening of tremolo strings and fragments of the Ninth Commissioned by the musicians of the Cabrillo Lola Montez Does the Spider Dance was Symphony signal octave-dropping motive, Festival Orchestra in honor of Marin Alsop commissioned by members of the Cabrillo Festival Orchestra in celebration of Marin the solo quartet emerged as if out of a haze, The Irish-born actress and dancer Eliza Gilbert Alsop’s twenty five seasons as music director, playing the driving foursquare figures of that (1821—1861) achieved international fame and it is dedicated to her. scherzo material that almost immediately went under the name “Lola Montez, the Spanish through a series of strange permutations. Dancer.” After a controversial career on the —John Adams continent, including a sojourn in Bavaria This original opening never satisfied me. The where she become both the lover as well as clarity of the solo quartet’s role was often political advisor to King Ludwig, she returned Absolute Jest (2011) buried beneath the orchestral activity resulting in what sounded to me too much like “chatter.” to London, where she eloped with and married John Adams (b. -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

Download Booklet

Acknowledgments This recording was made at the I would also like to thank the Teresa This disc is dedicated to all the Academy of Arts and Letters in Sterne Foundation, Gilbert Kalish, members of my family — especially Manhattan, New York on May and Norma Hurlburt for their gener- my mom, dad, Eve, Henry, and 26-28, 2007. Thank you to osity, which helped to make this my nephews — who have been a Ardith Holmgrain for her help disc a reality. And, a thank you to constant source of love and support in arranging our use of this Lehman College and its Shuster in my life; to my primary teachers magnificent recording space. Grant through the Research Jesslyn Kitts, Michael Zenge, Foundation of the City of New Leonard Hokanson, and Gilbert I would like to thank Max Wilcox, York for their help in the Kalish; to a cherished circle of who very graciously helped to completion of this disc. friends, which grows wider all the prepare and record this disc. time; and, to God who orchestrated Without his help it never could I would also like to thank Jeremy all of these parts. have happened. I also thank Mary Geffen, Ara Guzelemian, Kathy Schwendeman for the use of her Schumann, John Adams, Peter glorious Steinway. Thank you to Sellars, David Robertson, Dawn David Merrill who continuously Upshaw and the Carnegie Hall Publishers: t h r e a d s offered a bright smile and encour- family for giving me so many Andriessen: Boosey & Hawkes aging words during the engineering wonderfully rich treasures in my Music Publishers Limited and recording of this disc and musical experiences thus far. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

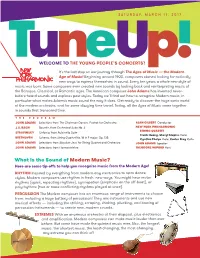

What Is the Sound of Modern Music?

SATURDAY, MARCH 11, 2017 Mozart’s “Classical” European tour? A TuWELCOMEn TO THE YOUNGe PEOPLE’SU CONCERTS!TM p! It’s the last stop on our journey through The Ages of Music — the Modern Age of Music! Beginning around 1900, composers started looking for radically new ways to express themselves in sound. Every ten years a whole new style of music was born. Some composers even created new sounds by looking back and reinterpreting music of the Baroque, Classical, or Romantic ages. The American composer John Adams has invented never- before-heard sounds and explores past styles. Today we’ll find out how to recognize Modern music, in particular what makes Adams’s music sound the way it does. Get ready to discover the huge sonic world of the modern orchestra, and for some dizzying time travel. Today, all the Ages of Music come together in sounds that transcend time. THE PROGRAM JOHN ADAMS Selections from The Chairman Dances, Foxtrot for Orchestra ALAN GILBERT Conductor J.S. BACH Bourrée, from Orchestral Suite No. 3 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC STRING QUARTET STRAVINSKY Sinfonia, from Pulcinella Suite Frank Huang, Sheryl Staples Violin BEETHOVEN Scherzo, from String Quartet No. 16 in F major, Op. 135 Cynthia Phelps Viola; Carter Brey Cello JOHN ADAMS Selections from Absolute Jest, for String Quartet and Orchestra JOHN ADAMS Speaker JOHN ADAMS Selections from Harmonielehre THEODORE WIPRUD Host What Is the Sound of Modern Music? Here are some tip-offs to help you recognize music from the Modern Age! RHYTHM Inspired by everything from modern-day electronics to retro dance styles, Modern composers use rhythm in fresh, new ways. -

Minimalism Post-Modernism Is a Term That Refers to Events After the So

Post-Modernism - Minimalism Post-Modernism is a term that refers to events after the so-called Modern period. The term suggests that we are now using what we learned in the “modern” period, but mixing it with ideas from the more distant past. A major movement within Post-Modernism is Minimalism Minimalism mixes some Eastern philosophical principles involving chant and meditation with simple tonal materials. Basic definition of Minimalism: sustained or repetitive use of simple (often tonal) materials. The movement began with LaMonte Young (b.1935); he used simple textures and consonant materials; often called trance music. Terry Riley (b.1935) is credited with first minimalist work In C (1964). The piece has repeated high C’s on piano maintaining simple pulse. Score has 53 short motives to be played by a group any size; players play all 53 figures, repeating as many times and as frequently as desired. Performance ends when all players are done with all 53 figures. Because figures change in content, there is subtle but constantly shifting texture all the time. Steve Reich (b. 1936) prefers to call his music “Structural” not minimal. His music is influenced by his study of African drumming. Some of his early works use phasing, where a tape loop is set up: the tape records first sounds made by performer; then plays them back while performer continues to play. More layers are added, and gradually live sounds get ahead of play-back. Effect can be hypnotic: trance-like. Violin Phase (1967) is example. In Mid-70’s Reich expanded his viewpoint and his ensemble: Music for 18 Musicians is a little like In C, but there is much more variation in patterns. -

My Father Knew Charles Ives Harmonielehre

AMERICAN CLASSICS JOHN ADAMS My Father Knew Charles Ives Harmonielehre Nashville Symphony Giancarlo Guerrero John Adams (b. 1947) My Father Knew Charles Ives • Harmonielehre My Father Knew Charles Ives is an intriguing, allusive with his father in the local Nevers’ Second Regimental reaches its apex, however, the music suddenly subsides, woodwinds introduce an insistent D (suggesting a title. But, as composer John Adams freely admits, his Band). When the parade begins (at 5:38), Adams mirroring “a moment of sudden, unexpected astonishment functional seventh chord, perhaps?), but the prevailing E father never met the iconoclastic New England composer, conjures up an Ivesian Fourth of July, although in this after a hard-won rush to the top.” minor triad persists, driven by a constant quarter-note much less knew him personally. In his memoir, Hallelujah instance the tunes only sound familiar. Rather than At the time he completed Harmonium for the San pulse in the bass and flurries of eighth notes in the rest of Junction: Composing an American Life (Farrar, Straus quoting established melodies as Ives often did, Adams Francisco Symphony and Chorus in 1981, Adams described the strings (and eventually woodwinds). The harmony and Giroux, 2008), he notes similarities between his creates his own. “Only a smirk from trumpets playing himself as “a Minimalist who is bored with Minimalism.” steadily thickens and becomes more complex until the father and George Ives, Connecticut bandmaster and Reveille and, in the coda, a hint of Ives’ beloved Nearer He was an artist who needed to move on creatively but pounding pulse relaxes and eases into a second “theme” father of Charles: “Both fathers were artistic and not My God to Thee are the genuine article,” he says. -

Miriam Gideon's Cantata, the Habitable Earth

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2003 Miriam Gideon's cantata, The aH bitable Earth: a conductor's analysis Stella Panayotova Bonilla Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bonilla, Stella Panayotova, "Miriam Gideon's cantata, The aH bitable Earth: a conductor's analysis" (2003). LSU Major Papers. 20. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/20 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MIRIAM GIDEON’S CANTATA, THE HABITABLE EARTH: A CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Stella Panayotova Bonilla B.M., State Academy of Music, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1991 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1994 August 2003 ©Copyright 2003 Stella Panayotova Bonilla All rights reserved ii DEDICATION To you mom, and to the memory of my beloved father. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to Dr. Kenneth Fulton for his guidance through the years, his faith in me and his invaluable help in accomplishing this project. Thanks to Dr. Robert Peck for his inspirational insight. Thanks to Dr. Cornelia Yarbrough and Dr. -

Guest Artist Recital: Emanuel Ax, Piano Emanuel Ax

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 10-22-2002 Guest Artist Recital: Emanuel Ax, piano Emanuel Ax Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ax, Emanuel, "Guest Artist Recital: Emanuel Ax, piano" (2002). All Concert & Recital Programs. 2527. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/2527 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 2002-3 Emanuel Ax, piano Variations in F on an Original Theme Ludwig Van Beethoven for Piano, Op. 34 (1770-1827) Partita No. 1 in B-flat, BWV 825 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Prelude Allemande Corrente Sarabande Minuet I and II Gigue Variations and Fugue in E-flat Major, Ludwig Van Beethoven Op. 35, "Eroica" INTERMISSION Polonaise-Fantaisie in A-flat Major, Op. 61 Frederic Chopin (1810-1849) Three Mazurkas Frederic Chopin Op. 59, no. 1 Op. 30, no. 2 Op. 56, no. 3 Andante Spianato and Grand Polonaise, Op. 22 Frederic Chopin Ford Hall Tuesday, October 22, 2002 8:15 p.m. .... xclusive Management: ICM Artists, Ltd., 40 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10019 Lee Lamont, Chairman David V. Foster, President and CEO Mr. Ax records exclusively for Sony Classical Steinway Piano EMANUEL AX Pianist Emanuel Ax is renowned not only for his poetic temperament and unsurpassed virtuosity, but also for the exceptional breadth of hi.