An HD Odyssey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Atomic

What to Expect from doctor atomic Opera has alwayS dealt with larger-than-life Emotions and scenarios. But in recent decades, composers have used the power of THE WORK DOCTOR ATOMIC opera to investigate society and ethical responsibility on a grander scale. Music by John Adams With one of the first American operas of the 21st century, composer John Adams took up just such an investigation. His Doctor Atomic explores a Libretto by Peter Sellars, adapted from original sources momentous episode in modern history: the invention and detonation of First performed on October 1, 2005, the first atomic bomb. The opera centers on Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, in San Francisco the brilliant physicist who oversaw the Manhattan Project, the govern- ment project to develop atomic weaponry. Scientists and soldiers were New PRODUCTION secretly stationed in Los Alamos, New Mexico, for the duration of World Alan Gilbert, Conductor War II; Doctor Atomic focuses on the days and hours leading up to the first Penny Woolcock, Production test of the bomb on July 16, 1945. In his memoir Hallelujah Junction, the American composer writes, “The Julian Crouch, Set Designer manipulation of the atom, the unleashing of that formerly inaccessible Catherine Zuber, Costume Designer source of densely concentrated energy, was the great mythological tale Brian MacDevitt, Lighting Designer of our time.” As with all mythological tales, this one has a complex and Andrew Dawson, Choreographer fascinating hero at its center. Not just a scientist, Oppenheimer was a Leo Warner and Mark Grimmer for Fifty supremely cultured man of literature, music, and art. He was conflicted Nine Productions, Video Designers about his creation and exquisitely aware of the potential for devastation Mark Grey, Sound Designer he had a hand in designing. -

Motion Film File Title Listing

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MOTION FILM FILE ● MFF-001 "On Guard for America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #1" (1950) One of a series of six: On Guard for America", TV Campaign spots. Features Richard M. Nixon speaking from his office" Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. Cross Reference: MVF 47 (two versions: 15 min and 30 min);. DVD reference copy available ● MFF-002 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #2" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. DVD reference copy available ● MFF-003 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #3" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office. Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. DVD reference copy available Monday, August 06, 2018 Page 1 of 202 Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MOTION FILM FILE ● MFF-004 "On Guard For America: Nixon for U.S. Senator TV Spot #4" (1950) One of a series of six "On Guard for America", TV campaign spots. Features Richard Nixon speaking from his office. Participants: Richard M. Nixon Original Format: 16mm film Film. Original source type: MPPCA. -

ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY DAVID ROBERTSON, CONDUCTOR Wednesday, March 29, 2017, at 7:30Pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM ST

ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY DAVID ROBERTSON, CONDUCTOR Wednesday, March 29, 2017, at 7:30pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY David Robertson, music director and conductor John Adams The Chairman Dances, Foxtrot for Orchestra (1985) (b. 1947) Aaron Copland Appalachian Spring, Ballet Suite for Orchestra (1944) (1900–1990) 20-minute intermission Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 7 in A major, op. 92 (1812) (1770–1827) Poco sostenuto; Vivace Allegretto Presto; Assai meno Allegro con brio 2 THANK YOU TO THE SPONSORS OF THIS PERFORMANCE GIVING OF ACT THE Krannert Center honors the spirited generosity of these committed sponsors whose support of this performance continues to strengthen the impact of the arts in our community. Krannert Center honors the memory of Endowed Underwriters Marilyn Pflederer Zimmerman & Vernon K. Zimmerman. Their lasting investment in the performing arts and our community will allow future generations to experience world-class performances such as this one. * Krannert Center gratefully acknowledges the continued generosity of Endowed Sponsors Mary & Kenneth Andersen. With their previous sponsorships, they demonstrate their dedication to sharing beautiful and significant cultural events with our community. *PHOTO CREDIT: ILLINI STUDIO 3 * * JAMES ECONOMY HELEN & DANIEL RICHARDS Special Support of Classical Music Twenty-Seven Previous Sponsorships * * THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE PEGGY MADDEN & MARY SCHULER & RICHARD PHILLIPS STEPHEN SLIGAR Fourteen Previous Sponsorships Five Previous Sponsorships Two Current Sponsorships -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

Download Booklet

Acknowledgments This recording was made at the I would also like to thank the Teresa This disc is dedicated to all the Academy of Arts and Letters in Sterne Foundation, Gilbert Kalish, members of my family — especially Manhattan, New York on May and Norma Hurlburt for their gener- my mom, dad, Eve, Henry, and 26-28, 2007. Thank you to osity, which helped to make this my nephews — who have been a Ardith Holmgrain for her help disc a reality. And, a thank you to constant source of love and support in arranging our use of this Lehman College and its Shuster in my life; to my primary teachers magnificent recording space. Grant through the Research Jesslyn Kitts, Michael Zenge, Foundation of the City of New Leonard Hokanson, and Gilbert I would like to thank Max Wilcox, York for their help in the Kalish; to a cherished circle of who very graciously helped to completion of this disc. friends, which grows wider all the prepare and record this disc. time; and, to God who orchestrated Without his help it never could I would also like to thank Jeremy all of these parts. have happened. I also thank Mary Geffen, Ara Guzelemian, Kathy Schwendeman for the use of her Schumann, John Adams, Peter glorious Steinway. Thank you to Sellars, David Robertson, Dawn David Merrill who continuously Upshaw and the Carnegie Hall Publishers: t h r e a d s offered a bright smile and encour- family for giving me so many Andriessen: Boosey & Hawkes aging words during the engineering wonderfully rich treasures in my Music Publishers Limited and recording of this disc and musical experiences thus far. -

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

On Nixon, 25 on Kissinger, and More Than 600 on Mao

Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Powers Nixon and Mao: The Week that Changed the World Roundtable Review Reviewed Works: Robert Dallek. Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Power. New York: Harper Collins, 2007. 740 pp. $32.50. ISBN-13: 978-0060722302 (hardcover). Margaret MacMillan. Nixon and Mao: The Week that Changed the World. New York: Random House, 2007. 404 pp. $27.95. ISBN-13: 978-1-4000- 6127-3 (hardcover). [Previously published in Canada as Nixon in China: The Week that Changed the World and in the UK as Seize the Hour: When Nixon Met Mao.]. Roundtable Editor: David A. Welch Reviewers: Jussi M. Hanhimäki, Jeffrey Kimball, Lorenz Lüthi, Yafeng Xia Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/NixonKissingerMao-Roundtable.pdf Your use of this H-Diplo roundtable review indicates your acceptance of the H-Net copyright policies, and terms of condition and use. The following is a plain language summary of these policies: You may redistribute and reprint this work under the following conditions: Attribution: You must include full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. Nonprofit and education purposes only. You may not use this work for commercial purposes. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Enquiries about any other uses of this material should be directed tothe H-Diplo editorial staff at h- [email protected]. H-Net’s copyright policy is available at http://www.h-net.org/about/intellectualproperty.php . -

ESO Highnotes November 2020

HighNotes is brought to you by the Evanston Symphony Orchestra for the senior members of our community who must of necessity isolate more because of COVID-!9. The current pandemic has also affected all of us here at the ESO, and we understand full well the frustration of not being able to visit with family and friends or sing in soul-renewing choirs or do simple, familiar things like choosing this apple instead of that one at the grocery store. We of course miss making music together, which is especially difficult because Musical Notes and Activities for Seniors this fall marks the ESO’s 75th anniversary – our Diamond Jubilee. While we had a fabulous season of programs planned, we haven’t from the Evanston Symphony Orchestra been able to perform in a live concert since February so have had to push the hold button on all live performances for the time being. th However, we’re making plans to celebrate our long, lively, award- Happy 75 Anniversary, ESO! 2 winning history in the spring. Until then, we’ll continue to bring you music and musical activities in these issues of HighNotes – or for Aaron Copland An American Voice 4 as long as the City of Evanston asks us to do so! O’Connor Appalachian Waltz 6 HighNotes always has articles on a specific musical theme plus a variety of puzzles and some really bad jokes and puns. For this issue we’re focusing on “Americana,” which seems appropriate for Gershwin Porgy and Bess 7 November, when we come together as a country to exercise our constitutional right and duty to vote for candidates of our choice Bernstein West Side Story 8 and then to gather with our family and friends for Thanksgiving and completely spoil a magnificent meal by arguing about politics… ☺ Tate Music of Native Americans 9 But no politics here, thank you! “Bygones” features things that were big in our childhoods, but have now all but disappeared. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

A Season of Thrilling Intrigue and Grand Spectacle –

A Season of Thrilling Intrigue and Grand Spectacle – Angel Blue as MimÌ in La bohème Fidelio Rigoletto Love fuels a revolution in Beethoven’s The revenger becomes the revenged in Verdi’s monumental masterpiece. captivating drama. Greetings and welcome to our 2020–2021 season, which we are so excited to present. We always begin our planning process with our dreams, which you might say is a uniquely American Nixon in China Così fan tutte way of thinking. This season, our dreams have come true in Step behind “the week that changed the world” in Fidelity is frivolous—or is it?—in Mozart’s what we’re able to offer: John Adams’s opera ripped from the headlines. rom-com. Fidelio, to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. Nixon in China by John Adams—the first time WNO is producing an opera by one of America’s foremost composers. A return to Russian music with Musorgsky’s epic, sweeping, spectacular Boris Godunov. Mozart’s gorgeous, complex, and Boris Godunov La bohème spiky view of love with Così fan tutte. Verdi’s masterpiece of The tapestry of Russia's history unfurls in Puccini’s tribute to young love soars with joy a family drama and revenge gone wrong in Rigoletto. And an Musorgsky’s tale of a tsar plagued by guilt. and heartbreak. audience favorite in our lavish production of La bohème, with two tremendous casts. Alongside all of this will continue our American Opera Initiative 20-minute operas in its 9th year. Our lineup of artists includes major stars, some of whom SPECIAL PRESENTATIONS we’re thrilled to bring to Washington for the first time, as well as emerging talents. -

A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form

MODERN FORMS OF AN ANCIENT ART: A SELECTION OF CONTEMPORARY FANFARES FOR MULTIPLE TRUMPETS DEMONSTRATING EVOLUTIONARY PROCESSES IN THE FANFARE FORM Paul J. Florek, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2015 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Florek, Paul J. Modern Forms of an Ancient Art: A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2015, 73 pp., 1 table, 26 figures, references, 96 titles. The pieces discussed throughout this dissertation provide evidence of the evolution of the fanfare and the ability of the fanfare, as a form, to accept modern compositional techniques. While Britten’s Fanfare for St. Edmundsbury maintains the harmonic series, it does so by choice rather than by the necessity in earlier music played by the baroque trumpet. Stravinsky’s Fanfare from Agon applies set theory, modal harmonies, and open chords to blend modern techniques with medieval sounds. Satie’s Sonnerie makes use of counterpoint and a rather unusual, new characteristic for fanfares, soft dynamics. Ginastera’s Fanfare for Four Trumpets in C utilizes atonality and jazz harmonies while Stravinsky’s Fanfare for a New Theatre strictly coheres to twelve-tone serialism. McTee’s Fanfare for Trumpets applies half-step dissonance and ostinato patterns while Tower’s Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman demonstrates a multi-section work with chromaticism and tritones. -

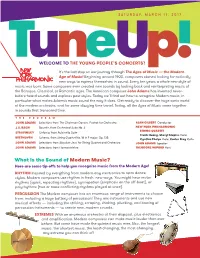

What Is the Sound of Modern Music?

SATURDAY, MARCH 11, 2017 Mozart’s “Classical” European tour? A TuWELCOMEn TO THE YOUNGe PEOPLE’SU CONCERTS!TM p! It’s the last stop on our journey through The Ages of Music — the Modern Age of Music! Beginning around 1900, composers started looking for radically new ways to express themselves in sound. Every ten years a whole new style of music was born. Some composers even created new sounds by looking back and reinterpreting music of the Baroque, Classical, or Romantic ages. The American composer John Adams has invented never- before-heard sounds and explores past styles. Today we’ll find out how to recognize Modern music, in particular what makes Adams’s music sound the way it does. Get ready to discover the huge sonic world of the modern orchestra, and for some dizzying time travel. Today, all the Ages of Music come together in sounds that transcend time. THE PROGRAM JOHN ADAMS Selections from The Chairman Dances, Foxtrot for Orchestra ALAN GILBERT Conductor J.S. BACH Bourrée, from Orchestral Suite No. 3 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC STRING QUARTET STRAVINSKY Sinfonia, from Pulcinella Suite Frank Huang, Sheryl Staples Violin BEETHOVEN Scherzo, from String Quartet No. 16 in F major, Op. 135 Cynthia Phelps Viola; Carter Brey Cello JOHN ADAMS Selections from Absolute Jest, for String Quartet and Orchestra JOHN ADAMS Speaker JOHN ADAMS Selections from Harmonielehre THEODORE WIPRUD Host What Is the Sound of Modern Music? Here are some tip-offs to help you recognize music from the Modern Age! RHYTHM Inspired by everything from modern-day electronics to retro dance styles, Modern composers use rhythm in fresh, new ways.