D3b1bdf3996e66f42682fee8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pediatric Eating Disorders

5/17/2017 How to Identify and Address Eating Disorders in Your Practice Dr. Susan R. Brill Chief, Division of Adolescent Medicine The Children’s Hospital at Saint Peter’s University Hospital Clinical Associate Professor of Pediatrics Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School Disclosure Statement I have no financial interest or other relationship with any manufacturer/s of any commercial product/s which may be discussed at this activity Credit for several illustrations and charts goes to Dr.Nonyelum Ebigbo, MD. PGY-2 of Richmond University Medical Center, Tavleen Sandhu MD PGY-3 and Alex Schosheim MD , PGY-2 of Saint Peter’s University Hospital Epidemiology Eating disorders relatively common: Anorexia .5% prevalence, estimate of disorder 1- 3%; peak ages 14 and 18 Bulimia 1-5% adolescents,4.5% college students 90% of patients are female,>95% are Caucasian 1 5/17/2017 Percentage of High School Students Who Described Themselves As Slightly or Very Overweight, by Sex,* Grade, and Race/Ethnicity,* 2015 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2015 Percentage of High School Students Who Were Overweight,* by Sex, Grade, and Race/Ethnicity,† 2015 * ≥ 85th percentile but <95th percentile for body mass index, based on sex- and age-specific reference data from the 2000 CDC growth charts National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2015 Percentage of High School Students Who Had Obesity,* by Sex,† Grade,† and Race/Ethnicity,† 2015 * ≥ 95th percentile for body mass index, based on sex- and age-specific reference data from the 2000 CDC growth charts †M > F; 10th > 12th; B > W, H > W (Based on t-test analysis, p < 0.05.) All Hispanic students are included in the Hispanic category. -

Welcome to the New Open Access Neurosci

Editorial Welcome to the New Open Access NeuroSci Lucilla Parnetti 1,* , Jonathon Reay 2, Giuseppina Martella 3 , Rosario Francesco Donato 4 , Maurizio Memo 5, Ruth Morona 6, Frank Schubert 7 and Ana Adan 8,9 1 Centro Disturbi della Memoria, Laboratorio di Neurochimica Clinica, Clinica Neurologica, Università di Perugia, 06132 Perugia, Italy 2 Department of Psychology, Teesside University, Victoria, Victoria Rd, Middlesbrough TS3 6DR, UK; [email protected] 3 Laboratory of Neurophysiology and Plasticity, Fondazione Santa Lucia, and University of Rome Tor Vergata, 00143 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Perugia, 06132 Perugia, Italy; [email protected] 5 Department of Molecular and Translational Medicine, University of Brescia, 25123 Brescia, Italy; [email protected] 6 Department of Cell Biology, School of Biology, University Complutense of Madrid, Av. Jose Antonio Novais 12, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 7 School of Biological Sciences, University of Portsmouth, Hampshire PO1 2DY, UK; [email protected] 8 Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychobiology, University of Barcelona, 08035 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 9 Institute of Neurosciences, University of Barcelona, 08035 Barcelona, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 August 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020; Published: 3 September 2020 Message from Editor-in-Chief: Prof. Dr. Lucilla Parnetti With sincere satisfaction and pride, I present to you the new journal, NeuroSci, for which I am pleased to serve as editor-in-chief. To date, the world of neurology has been rapidly advancing, NeuroSci is a cross-disciplinary, open-access journal that offers an opportunity for presentation of novel data in the field of neurology and covers a broad spectrum of areas including neuroanatomy, neurophysiology, neuropharmacology, clinical research and clinical trials, molecular and cellular neuroscience, neuropsychology, cognitive and behavioral neuroscience, and computational neuroscience. -

Historical Notes Distaff Side

HISTORICAL NOTES on. the DISTAFF SIDE MARION WALLACE RENINGER HARRIET LANE The most famous of Lancaster County women was Harriet Lane, niece of President James Buchanan, who was born in Mercersburg, Penn- sylvania. She was the daughter of Jane Buchanan, James' favorite sister, and Elliot T. Lane, descendant of an old Virginia family. Jane's father, the elder James Buchanan, was a merchant, who had acquired wealth in trading at the Mercersburg stop on the great highway from east to west. Elliot Lane was also a merchant and his father-in-law transferred much of his trade 'to this son-in-law, Jane's husband. However, Mr. Lane died when Harriet was seven and two years later her mother died, leaving another girl and two boys as orphans. Her uncle and guardian, James Buchanan, invited her to come to live with him at his house in Lancaster. He also gave a home to another sister's orphan son, James Buchanan Henry, and to Harriet's younger brother, Elliot Eskbridge Lane. In reading letters written from Washington to Harriet in Lancaster the then Senator Buchanan shows his deep attention to Harriet's welfare and education. She attended a small private school for three years, prob- ably Miss Young's. Later she was sent to a boarding school in Lancaster kept by the Misses Crawford. Here she complained in letters to her uncle of "the strict rules, early hours, brown sugar in the tea and restrictions in dress." Here she was not very happy, as she was a mischievous and high spirited girl, who loved to play practical jokes and made many friends, but resented the school's strict disciplines. -

The Creation of Neuroscience

The Creation of Neuroscience The Society for Neuroscience and the Quest for Disciplinary Unity 1969-1995 Introduction rom the molecular biology of a single neuron to the breathtakingly complex circuitry of the entire human nervous system, our understanding of the brain and how it works has undergone radical F changes over the past century. These advances have brought us tantalizingly closer to genu- inely mechanistic and scientifically rigorous explanations of how the brain’s roughly 100 billion neurons, interacting through trillions of synaptic connections, function both as single units and as larger ensem- bles. The professional field of neuroscience, in keeping pace with these important scientific develop- ments, has dramatically reshaped the organization of biological sciences across the globe over the last 50 years. Much like physics during its dominant era in the 1950s and 1960s, neuroscience has become the leading scientific discipline with regard to funding, numbers of scientists, and numbers of trainees. Furthermore, neuroscience as fact, explanation, and myth has just as dramatically redrawn our cultural landscape and redefined how Western popular culture understands who we are as individuals. In the 1950s, especially in the United States, Freud and his successors stood at the center of all cultural expla- nations for psychological suffering. In the new millennium, we perceive such suffering as erupting no longer from a repressed unconscious but, instead, from a pathophysiology rooted in and caused by brain abnormalities and dysfunctions. Indeed, the normal as well as the pathological have become thoroughly neurobiological in the last several decades. In the process, entirely new vistas have opened up in fields ranging from neuroeconomics and neurophilosophy to consumer products, as exemplified by an entire line of soft drinks advertised as offering “neuro” benefits. -

Brain Stimulation and Neuroplasticity

brain sciences Editorial Brain Stimulation and Neuroplasticity Ulrich Palm 1,2,* , Moussa A. Chalah 3,4 and Samar S. Ayache 3,4 1 Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Klinikum der Universität München, 80336 Munich, Germany 2 Medical Park Chiemseeblick, Rasthausstr. 25, 83233 Bernau-Felden, Germany 3 EA4391 Excitabilité Nerveuse & Thérapeutique, Université Paris Est Créteil, 94010 Créteil, France; [email protected] (M.A.C.); [email protected] (S.S.A.) 4 Service de Physiologie—Explorations Fonctionnelles, Hôpital Henri Mondor, Assistance Publique—Hôpitaux de Paris, 94010 Créteil, France * Correspondence: [email protected] Electrical or magnetic stimulation methods for brain or nerve modulation have been widely known for centuries, beginning with the Atlantic torpedo fish for the treatment of headaches in ancient Greece, followed by Luigi Galvani’s experiments with frog legs in baroque Italy, and leading to the interventional use of brain stimulation methods across Europe in the 19th century. However, actual research focusing on the development of tran- scranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is beginning in the 1980s and transcranial electrical brain stimulation methods, such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), tran- scranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), and transcranial random noise stimulation (tRNS), are investigated from around the year 2000. Today, electrical, or magnetic stimulation methods are used for either the diagnosis or exploration of neurophysiology and neuroplasticity functions, or as a therapeutic interven- tion in neurologic or psychiatric disorders (i.e., structural damage or functional impairment of central or peripheral nerve function). This Special Issue ‘Brain Stimulation and Neuroplasticity’ gathers ten research articles Citation: Palm, U.; Chalah, M.A.; and two review articles on various magnetic and electrical brain stimulation methods in Ayache, S.S. -

A Tale of Two Brains – Cortical Localization and Neurophysiology in the 19Th and 20Th Century

Commentary A Tale of Two Brains – Cortical localization and neurophysiology in the 19th and 20th century Philippe-Antoine Bilodeau, MDCM(c)1 MJM 2018 16(5) Abstract Introduction: Others have described the importance of experimental physiology in the development of the brain sciences and the individual discoveries by the founding fathers of modern neurology. This paper instead discusses the birth of neurological sciences in the 19th and 20th century and their epistemological origins. Discussion: In the span of two hundred years, two different conceptions of the brain emerged: the neuroanatomical brain, which arose from the development of functional, neurological and neurosurgical localization, and the neurophysiological brain, which relied on the neuron doctrine and enabled pre-modern electrophysiology. While the neuroanatomical brain stems from studying brain function, the neurophysiological brain emphasizes brain functioning and aims at understanding mechanisms underlying neurological processes. Conclusion: In the 19th and 20th century, the brain became an organ with an intelligible and coherent physiology. However, the various discoveries were tributaries of two different conceptions of the brain, which continue to influence sciences to this day. Relevance: With modern cognitive neuroscience, functional neuroanatomy, cellular and molecular neurophysiology and neural networks, there are different analytical units for each type of neurological science. Such a divide is a vestige of the 19th and 20th century development of the neuroanatomical and neurophysiological brains. history of medicine, history of neurology, cortical localization, neurophysiology, neuroanatomy, 19th century 1Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montréal, Canada. 3Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Sciences, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. Corresponding Author: Kamiar Mireskandari, email [email protected]. -

Redalyc.An International Curriculum for Neuropsychiatry And

Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría ISSN: 0034-7450 [email protected] Asociación Colombiana de Psiquiatría Colombia Sachdev, Perminder; Mohan, Adith An International Curriculum for Neuropsychiatry and Behavioural Neurology Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, vol. 46, núm. 1, 2017, pp. 18-27 Asociación Colombiana de Psiquiatría Bogotá, D.C., Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=80654036004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative rev colomb psiquiat. 2017;46(S1):18–27 www.elsevier.es/rcp Review Article An International Curriculum for Neuropsychiatry and Behavioural Neurology Perminder Sachdev ∗, Adith Mohan Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing, School of Psychiatry University of New South Wales Neuropsychiatric Institute Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney, Australia article info abstract Article history: With major advances in neuroscience in the last three decades, there is an emphasis on Received 13 April 2017 understanding disturbances in thought, behaviour and emotion in terms of their neuro- Accepted 6 May 2017 scientific underpinnings. While psychiatry and neurology, both of which deal with brain Available online 16 June 2017 diseases, have a historical standing as distinct disciplines, there has been an increasing need to have a combined neuropsychiatric approach to deal with many conditions and dis- Keywords: orders. Additionally, there is a body of disorders and conditions that warrants the skills sets Neuropsychiatry and knowledge bases of both disciplines. This is the territory covered by the subspecialty Behavioural neurology of Neuropsychiatry from a ‘mental’ health perspective and Behavioural Neurology from a Curriculum ‘brain’ health perspective. -

Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady Rachel Morris College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Morris, Rachel, "Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 289. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in American Studies from the College of William and Mary in Virginia. Rachel Diane Morris Accepted for ________________________________ _________________________________________ Timothy Barnard, Director _________________________________________ Chandos Brown _________________________________________ Susan Kern _________________________________________ Charles McGovern 2 Table of -

Ranking America's First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary Moves from 2 to 5 ; Jackie

For Immediate Release: Monday, September 29, 2003 Ranking America’s First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 nd Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary moves from 2 nd to 5 th ; Jackie Kennedy from 7 th th to 4 Mary Todd Lincoln Up From Usual Last Place Loudonville, NY - After the scrutiny of three expert opinion surveys over twenty years, Eleanor Roosevelt is still ranked first among all other women who have served as America’s First Ladies, according to a recent expert opinion poll conducted by the Siena (College) Research Institute (SRI). In other news, Mary Todd Lincoln (36 th ) has been bumped up from last place by Jane Pierce (38 th ) and Florence Harding (37 th ). The Siena Research Institute survey, conducted at approximate ten year intervals, asks history professors at America’s colleges and universities to rank each woman who has been a First Lady, on a scale of 1-5, five being excellent, in ten separate categories: *Background *Integrity *Intelligence *Courage *Value to the *Leadership *Being her own *Public image country woman *Accomplishments *Value to the President “It’s a tracking study,” explains Dr. Douglas Lonnstrom, Siena College professor of statistics and co-director of the First Ladies study with Thomas Kelly, Siena professor-emeritus of American studies. “This is our third run, and we can chart change over time.” Siena Research Institute is well known for its Survey of American Presidents, begun in 1982 during the Reagan Administration and continued during the terms of presidents George H. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush (http://www.siena.edu/sri/results/02AugPresidentsSurvey.htm ). -

Harriet Lane Johnston May 9, 1830 - July 3, 1903

Harriet Lane Johnston May 9, 1830 - July 3, 1903 John Henry Brown, Harriet Lane Johnston 1878 Smithsonian American Art Museum Bequest of May S. Kennedy Printed on the occasion of The Harriet Lane Johnston Symposium June 10, 2015 Edwards Room in Keil Hall at Mercersburg Academy Presented by the Mercersburg Historical Society Harriet Lane Johnston Joan C. McCulloh Harriet Lane’s education, both formal and seven hundred residents was busy. In addition to informal, prepared her well for the responsibilities her father, who had a dry goods store but seems to that lay ahead of her. have left that business about the time of her birth, Harriet Rebecca Lane, later Harriet Lane John- several other merchants had stores.The town was ston, niece of President James Buchanan, was busy with cabinetmakers, shoemakers, wagon hostess in the White House during her uncle’s makers, carpenters, chair makers, saddlers, coo- Presidency from 1857 to 1861.The daughter of pers, blacksmiths, a potter, weavers, silversmiths, Elliott Tole Lane, whose family was from the area and others, a little self-reliant community. of Charles Town, Virginia, now West Virginia, and Her father, Elliott Lane, was important in Jane Buchanan Lane, she was born in Mercersburg the affairs of the town. When the German Re- on May 9, 1830, in a large brick house across the formed Church placed an advertisement in area street from what had been her Grandfather Bu- newspapers in search of a place to move its high chanan’s store and home. school and seminary then located in York, Elliott She was baptized on June 10, 1830, in the local Lane was one of the local men who signed a letter Presbyterian Church of the Upper West Conoco- indicating that men in Mercersburg would offer cheague by the Reverend David Elliott who had $10,000 to the church if it moved its school here. -

The Pennsylvania Presidency the Efforts and Effects of the Buchanan Administration Contents

The Pennsylvania Presidency The Efforts and Effects of the Buchanan Administration Contents • “James Buchanan as a Lawyer” • James Buchanan’s Inaugural Address • W.U. Hensel’s address at the University • The Constitution in Hand and at of Pennsylvania Mind • Ceremonial Japanese porcelain bowl • McMaster’s painting of Buchanan • Gift of State under President Buchanan from Japanese delegation • James Buchanan, the Conservatives’ Choice 1856: A Political Portrait • Wheatland • Philip G. Auchampaugh, University of • James Buchanan’s Lancaster mansion Nevada • From the first First Lady • His Lasting Legacy • Harriet Lane Johnston’s dress • Buchanan’s Statue • Campaign Ribbon • James Buchanan Film • The 1856 Campaign • A Documentary by LancasterHistory Questions to Consider Questions to Consider • How did Buchanan’s early career prepare him for public office? • What were some of the central points of Buchanan’s policy? • How is Buchanan remembered? Is this accurate? Contents James Buchanan as a Lawyer W.U. Hensel’s address at the University of Pennsylvania “When he became a legislator, having been elected to Congress in 1820, he had opportunity to reveal the character and to exercise the qualities of a constitutional lawyer.” Contents Questions to Consider James Buchanan as a Lawyer W.U. Hensel’s address at the University of Pennsylvania Questions to Consider • Do you notice any bias in the author’s writing? If so, how do you think Hensel personally feels about Buchanan? • How did Buchanan’s law career prepare him for public office? • How can you try to filter out bias from sources? Why is it important to acknowledge? Contents Questions to Consider Ceremonial Japanese porcelain bowl Gift of State under President Buchanan from Japanese delegation Contents Questions to Consider Ceremonial Japanese porcelain bowl Gift of State under President Buchanan from Japanese delegation Physical Description Extremely large Japanese porcelain bowl. -

Classes Without Quizzes-Edited

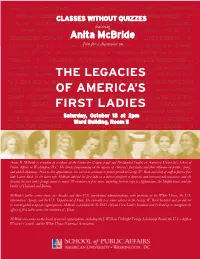

MARTHA WAS H INGTON A BIGA IL A DA M S MARTHA JEFFERSON DOLLEY MADISON S S ELISZ WABETHO MONROE LSO UISA A D A M S RACHEL JAC KS O N H ANNA H VA N B UREN A N NA H A RRIS O N featuring L ETITI A T YLER JULIA T YLE R S A R AH P OLK MARG A RET TAY L OR AnBIitGaAIL FcILBL MrOREide J A N E PIER C E 11 12 H A RRIET L ANE MAR YJoin T ODDfor a discussion L INC OonL N E LIZ A J OHN S O N JULIA GRANT L U C Y H AY E S LUC RETIA GARFIELD ELLEN ARTHUR FRANCES CLEVELAND CAROLINE HARRISON 10 IDA MCKINLEY EDITH ROOSEVELT HELEN TAFT ELLEN WILSON photographers, presidential advisers, and social secretaries to tell the stories through “Legacies of America’s E DITH WILSON F LORENCE H ARDING GRACE COOLIDGE First Ladies conferences LOU HOOVER ELEANOR ROOSEVELT ELIZABETH “BESS”TRUMAN in American politics and MAMIE EISENHOWER JACQUELINE KENNEDY CLAUDIA “LADY for their support of this fascinating series.” history. No place else has the crucial role of presidential BIRD” JOHNSON PAT RICIA “PAT” N IXON E LIZABET H “ BETTY wives been so thoroughly and FORD ROSALYN C ARTER NANCY REAGAN BARBAR A BUSH entertainingly presented.” —Cokie Roberts, political H ILLARY R O DHAM C L INTON L AURA BUSH MICHELLE OBAMA “I cannot imagine a better way to promote understanding and interest in the experiences of commentator and author of Saturday, October 18 at 2pm MARTHA WASHINGTON ABIGAIL ADAMS MARTHA JEFFERSON Founding Mothers: The Women Ward Building, Room 5 Who Raised Our Nation and —Doris Kearns Goodwin, presidential historian DOLLEY MADISON E LIZABETH MONROE LOUISA ADAMS Ladies of Liberty: The Women Who Shaped Our Nation About Anita McBride Anita B.