Arxiv:2008.00328V3 [Math.DS] 28 Apr 2021 Uniformly Hyperbolic and Topologically Mixing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Math.GT] 9 Oct 2020 Symmetries of Hyperbolic 4-Manifolds](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4430/math-gt-9-oct-2020-symmetries-of-hyperbolic-4-manifolds-394430.webp)

[Math.GT] 9 Oct 2020 Symmetries of Hyperbolic 4-Manifolds

Symmetries of hyperbolic 4-manifolds Alexander Kolpakov & Leone Slavich R´esum´e Pour chaque groupe G fini, nous construisons des premiers exemples explicites de 4- vari´et´es non-compactes compl`etes arithm´etiques hyperboliques M, `avolume fini, telles M G + M G que Isom ∼= , ou Isom ∼= . Pour y parvenir, nous utilisons essentiellement la g´eom´etrie de poly`edres de Coxeter dans l’espace hyperbolique en dimension quatre, et aussi la combinatoire de complexes simpliciaux. C¸a nous permet d’obtenir une borne sup´erieure universelle pour le volume minimal d’une 4-vari´et´ehyperbolique ayant le groupe G comme son groupe d’isom´etries, par rap- port de l’ordre du groupe. Nous obtenons aussi des bornes asymptotiques pour le taux de croissance, par rapport du volume, du nombre de 4-vari´et´es hyperboliques ayant G comme le groupe d’isom´etries. Abstract In this paper, for each finite group G, we construct the first explicit examples of non- M M compact complete finite-volume arithmetic hyperbolic 4-manifolds such that Isom ∼= G + M G , or Isom ∼= . In order to do so, we use essentially the geometry of Coxeter polytopes in the hyperbolic 4-space, on one hand, and the combinatorics of simplicial complexes, on the other. This allows us to obtain a universal upper bound on the minimal volume of a hyperbolic 4-manifold realising a given finite group G as its isometry group in terms of the order of the group. We also obtain asymptotic bounds for the growth rate, with respect to volume, of the number of hyperbolic 4-manifolds having a finite group G as their isometry group. -

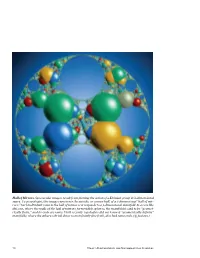

Apollonian Circle Packings: Dynamics and Number Theory

APOLLONIAN CIRCLE PACKINGS: DYNAMICS AND NUMBER THEORY HEE OH Abstract. We give an overview of various counting problems for Apol- lonian circle packings, which turn out to be related to problems in dy- namics and number theory for thin groups. This survey article is an expanded version of my lecture notes prepared for the 13th Takagi lec- tures given at RIMS, Kyoto in the fall of 2013. Contents 1. Counting problems for Apollonian circle packings 1 2. Hidden symmetries and Orbital counting problem 7 3. Counting, Mixing, and the Bowen-Margulis-Sullivan measure 9 4. Integral Apollonian circle packings 15 5. Expanders and Sieve 19 References 25 1. Counting problems for Apollonian circle packings An Apollonian circle packing is one of the most of beautiful circle packings whose construction can be described in a very simple manner based on an old theorem of Apollonius of Perga: Theorem 1.1 (Apollonius of Perga, 262-190 BC). Given 3 mutually tangent circles in the plane, there exist exactly two circles tangent to all three. Figure 1. Pictorial proof of the Apollonius theorem 1 2 HEE OH Figure 2. Possible configurations of four mutually tangent circles Proof. We give a modern proof, using the linear fractional transformations ^ of PSL2(C) on the extended complex plane C = C [ f1g, known as M¨obius transformations: a b az + b (z) = ; c d cz + d where a; b; c; d 2 C with ad − bc = 1 and z 2 C [ f1g. As is well known, a M¨obiustransformation maps circles in C^ to circles in C^, preserving angles between them. -

On Eigenvalues of Geometrically Finite Hyperbolic Manifolds With

On Eigenvalues of Geometrically Finite Hyperbolic Manifolds with Infinite Volume Xiaolong Hans Han April 6, 2020 Abstract Let M be an oriented geometrically finite hyperbolic manifold of dimension n ≥ 3 with infinite volume. Then for all k ≥ 0, we provide a lower bound on the k-th eigenvalue of the Laplacian operator acting on functions on M by a constant and the k-th eigenvalue of some neighborhood Mf of the thick part of the convex core. 1. Introduction As analytic data of a manifold, the spectrum of the Laplacian operator acting on func- tions contains rich information about the geometry and topology of a manifold. For example, by results of Cheeger and Buser, with a lower bound on Ricci curvature, the first eigenvalue is equivalent to the Cheeger constant of a manifold, which depends on the geometry of the manifold. The rigidity and richness of hyperbolic geometry make the connection even more intriguing: by Canary [4], for infinite volume, topologically tame hyperbolic 3-manifolds, the 2 bottom of the L -spectrum of −∆, denoted by λ0, is zero if and only if the manifold is not geometrically finite. If λ0 of a geometrically finite, infinite volume hyperbolic manifold is 1, by Canary and Burger [2], the manifold is either the topological interior of a handlebody or an R-bundle over a closed surface, which is a very strong topological restriction. Conversely, if we have data about the geometry of a manifold, we can convert it into data about its spectrum, like lower bounds on eigenvalues, dimensions of eigenspaces, existence of embedded eigenvalues, etc. -

ISOMETRY TRANSFORMATIONS of HYPERBOLIC 3-MANIFOLDS Sadayoshi KOJIMA 0. Introduction by a Hyperbolic Manifold, We Mean a Riemanni

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Topology and its Applications 29 (1988) 297-307 297 North-Holland ISOMETRY TRANSFORMATIONS OF HYPERBOLIC 3-MANIFOLDS Sadayoshi KOJIMA Department of Information Science, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Ohokayama, Meguro, Tokyo, Japan Received 1 December 1986 Revised 10 June 1987 The isometry group of a compact hyperbolic manifold is known to be finite. We show that every finite group is realized as the full isometry group of some compact hyperbolic 3-manifold. AMS (MOS) Subj. Class.: 57S17, 53C25, 57M99 3-manifold hyperbolic manifold isometry 0. Introduction By a hyperbolic manifold, we mean a Riemannian manifold with constant sectional curvature -1. It is known by several ways that the isometry group of a hyperbolic manifold of finite volume is finite. On the other hand, Greenberg has shown in [3] that every finite group is realized as the full conformal automorphism group of some Riemann surface of hyperbolic type. Since such a Riemann surface, which is a 2-manifold with a conformal structure, inherits a unique conformally equivalent hyperbolic structure through the uniformization theorem, there are no limitations on the group structure of the full isometry group of a hyperbolic manifold in dimension 2. In this paper, we first give a quick proof of the theorem of Greenberg quoted above, and then along the same line we show, raising the dimension by one. Theorem. Every jinite group is realized as the full isometry group of some closed hyperbolic 3 -manifold. An immediate corollary to this is the following. -

Hyperbolic Geometry

Flavors of Geometry MSRI Publications Volume 31,1997 Hyperbolic Geometry JAMES W. CANNON, WILLIAM J. FLOYD, RICHARD KENYON, AND WALTER R. PARRY Contents 1. Introduction 59 2. The Origins of Hyperbolic Geometry 60 3. Why Call it Hyperbolic Geometry? 63 4. Understanding the One-Dimensional Case 65 5. Generalizing to Higher Dimensions 67 6. Rudiments of Riemannian Geometry 68 7. Five Models of Hyperbolic Space 69 8. Stereographic Projection 72 9. Geodesics 77 10. Isometries and Distances in the Hyperboloid Model 80 11. The Space at Infinity 84 12. The Geometric Classification of Isometries 84 13. Curious Facts about Hyperbolic Space 86 14. The Sixth Model 95 15. Why Study Hyperbolic Geometry? 98 16. When Does a Manifold Have a Hyperbolic Structure? 103 17. How to Get Analytic Coordinates at Infinity? 106 References 108 Index 110 1. Introduction Hyperbolic geometry was created in the first half of the nineteenth century in the midst of attempts to understand Euclid’s axiomatic basis for geometry. It is one type of non-Euclidean geometry, that is, a geometry that discards one of Euclid’s axioms. Einstein and Minkowski found in non-Euclidean geometry a This work was supported in part by The Geometry Center, University of Minnesota, an STC funded by NSF, DOE, and Minnesota Technology, Inc., by the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, and by NSF research grants. 59 60 J. W. CANNON, W. J. FLOYD, R. KENYON, AND W. R. PARRY geometric basis for the understanding of physical time and space. In the early part of the twentieth century every serious student of mathematics and physics studied non-Euclidean geometry. -

Hyperbolic Geometry, Surfaces, and 3-Manifolds Bruno Martelli

Hyperbolic geometry, surfaces, and 3-manifolds Bruno Martelli Dipartimento di Matematica \Tonelli", Largo Pontecorvo 5, 56127 Pisa, Italy E-mail address: martelli at dm dot unipi dot it version: december 18, 2013 Contents Introduction 1 Copyright notices 1 Chapter 1. Preliminaries 3 1. Differential topology 3 1.1. Differentiable manifolds 3 1.2. Tangent space 4 1.3. Differentiable submanifolds 6 1.4. Fiber bundles 6 1.5. Tangent and normal bundle 6 1.6. Immersion and embedding 7 1.7. Homotopy and isotopy 7 1.8. Tubolar neighborhood 7 1.9. Manifolds with boundary 8 1.10. Cut and paste 8 1.11. Transversality 9 2. Riemannian geometry 9 2.1. Metric tensor 9 2.2. Distance, geodesics, volume. 10 2.3. Exponential map 11 2.4. Injectivity radius 12 2.5. Completeness 13 2.6. Curvature 13 2.7. Isometries 15 2.8. Isometry group 15 2.9. Riemannian manifolds with boundary 16 2.10. Local isometries 16 3. Measure theory 17 3.1. Borel measure 17 3.2. Topology on the measure space 18 3.3. Lie groups 19 3.4. Haar measures 19 4. Algebraic topology 19 4.1. Group actions 19 4.2. Coverings 20 4.3. Discrete groups of isometries 20 v vi CONTENTS 4.4. Cell complexes 21 4.5. Aspherical cell-complexes 22 Chapter 2. Hyperbolic space 25 1. The models of hyperbolic space 25 1.1. Hyperboloid 25 1.2. Isometries of the hyperboloid 26 1.3. Subspaces 27 1.4. The Poincar´edisc 29 1.5. The half-space model 31 1.6. -

Hyperbolic Deep Learning for Chinese Natural Language Understanding

Hyperbolic Deep Learning for Chinese Natural Language Understanding Marko Valentin Micic1 and Hugo Chu2 Kami Intelligence Ltd, HK SAR [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Recently hyperbolic geometry has proven to be effective in building embeddings that encode hierarchical and entailment information. This makes it particularly suited to modelling the complex asymmetrical relationships between Chinese characters and words. In this paper we first train a large scale hyperboloid skip-gram model on a Chinese corpus, then apply the character embeddings to a downstream hyperbolic Transformer model derived from the principles of gyrovector space for Poincare disk model. In our experiments the character-based Transformer outperformed its word-based Euclidean equivalent. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time in Chinese NLP that a character-based model outperformed its word- based counterpart, allowing the circumvention of the challenging and domain-dependent task of Chinese Word Segmentation (CWS). 1 Introduction Recent advances in deep learning have seen tremendous improvements in accuracy and scalability in all fields of application. Natural language processing (NLP), however, still faces many challenges, particularly in Chinese, where even word-segmentation proves to be a difficult and as-yet unscalable task. Traditional neural network architectures employed to tackle NLP tasks are generally cast in the standard Euclidean geometry. While this setting is adequate for most deep learning tasks, where it has often allowed for the achievement of superhuman performance in certain areas (e.g. AlphaGo [35], ImageNet [36]), its performance in NLP has yet to reach the same levels. Recent research arXiv:1812.10408v1 [cs.CL] 11 Dec 2018 indicates that some of the problems NLP faces may be much more fundamental and mathematical in nature. -

Hyperbolic Geometry

Flavors of Geometry MSRI Publications Volume 31, 1997 Hyperbolic Geometry JAMES W. CANNON, WILLIAM J. FLOYD, RICHARD KENYON, AND WALTER R. PARRY Contents 1. Introduction 59 2. The Origins of Hyperbolic Geometry 60 3. Why Call it Hyperbolic Geometry? 63 4. Understanding the One-Dimensional Case 65 5. Generalizing to Higher Dimensions 67 6. Rudiments of Riemannian Geometry 68 7. Five Models of Hyperbolic Space 69 8. Stereographic Projection 72 9. Geodesics 77 10. Isometries and Distances in the Hyperboloid Model 80 11. The Space at Infinity 84 12. The Geometric Classification of Isometries 84 13. Curious Facts about Hyperbolic Space 86 14. The Sixth Model 95 15. Why Study Hyperbolic Geometry? 98 16. When Does a Manifold Have a Hyperbolic Structure? 103 17. How to Get Analytic Coordinates at Infinity? 106 References 108 Index 110 1. Introduction Hyperbolic geometry was created in the first half of the nineteenth century in the midst of attempts to understand Euclid’s axiomatic basis for geometry. It is one type of non-Euclidean geometry, that is, a geometry that discards one of Euclid’s axioms. Einstein and Minkowski found in non-Euclidean geometry a ThisworkwassupportedinpartbyTheGeometryCenter,UniversityofMinnesota,anSTC funded by NSF, DOE, and Minnesota Technology, Inc., by the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, and by NSF research grants. 59 60 J. W. CANNON, W. J. FLOYD, R. KENYON, AND W. R. PARRY geometric basis for the understanding of physical time and space. In the early part of the twentieth century every serious student of mathematics and physics studied non-Euclidean geometry. This has not been true of the mathematicians and physicists of our generation. -

Quasi-Isometries of Graph Manifolds Do Not Preserve Non-Positive Curvature

QUASI-ISOMETRIES OF GRAPH MANIFOLDS DO NOT PRESERVE NON-POSITIVE CURVATURE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Andrew Nicol, MS Graduate Program in Mathematics The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jean-Fran¸coisLafont, Advisor Brian Ahmer Nathan Broaddus Michael Davis c Copyright by Andrew Nicol 2014 ABSTRACT Continuing the work of Frigerio, Lafont, and Sisto [8], we recall the definition of high dimensional graph manifolds. They are compact, smooth manifolds which decompose into finitely many pieces, each of which is a hyperbolic, non-compact, finite volume manifold of some dimension with toric cusps which has been truncated at the cusps and crossed with an appropriate dimensional torus. This class of manifolds is a generalization of two of the geometries described in Thurston's geometrization conjecture: H3 and H2 × R. In their monograph, Frigerio, Lafont, and Sisto describe various rigidity results and prove the existence of infinitely many graph manifolds not supporting a locally CAT(0) metric. Their proof relies on the existence of a cochain having infinite order. They leave open the question of whether or not there exists pairs of graph manifolds with quasi-isometric fundamental group but where one supports a locally CAT(0) metric while the other cannot. Using a number of facts about bounded cohomology and relative hyperbolicity, I extend their result, showing that there exists a cochain that is not only of infinite order but is also bounded. I also show that this is sufficient to construct two graph manifolds with the desired properties. -

Classifying Hyperbolic Manifolds— All’S Well That Ends Well Danamackenzie

Hall of Mirrors. Spectacular images result from plotting the action of a Kleinian group in 3-dimensional space. To a topologist, this image represents the outside, or convex hull, of a 3-dimensional “hall of mir- rors.” Each individual room in the hall of mirrors corresponds to a 3-dimensional manifold. In a case like this one, where the walls of the hall of mirrors form visible spheres, the manifold is said to be “geomet- rically finite,” and its ends are tame. Until recently topologists did not know if “geometrically infinite” manifolds, where the spheres shrink down to an infinitely fine froth, also had tame ends. (c JosLeys.) 14 What’s Happening in the Mathematical Sciences Classifying Hyperbolic Manifolds— All’s Well That Ends Well DanaMackenzie hile the status of one famous unsolved problem in topology remained uncertain, topologists conquered Wfour other major problems in 2004. The four theorems that went into this unique sundae—the Ending Laminations Conjecture, the Tame Ends Conjecture, the Ahlfors Measure Conjecture, and the Density Conjecture—were not household names, even among mathematicians. Yet to topologists who study three-dimensional spaces, they were as familiar (and went together as well) as chocolate, vanilla, hot fudge sauce and a maraschino cherry. The Poincaré Conjecture (see “First of Seven Millennium Danny Calegari. (Photo courtesy Problems Nears Completion,” p. 2) can be compared to the of Danny Calegari.) quest for the Loch Ness Monster: Whether you discover it or prove it doesn’t exist, fame and glory are sure to follow. On the other hand, if topologists spent all their time hunting Loch Ness monsters, the subject would never advance. -

A Short Proof of Unique Ergodicity of Horospherical Foliations on Infinite Volume Hyperbolic Manifolds Tome 8, No 1 (2016), P

CONFLUENTES MATHEMATICI Barbara SCHAPIRA A short proof of unique ergodicity of horospherical foliations on infinite volume hyperbolic manifolds Tome 8, no 1 (2016), p. 165-174. <http://cml.cedram.org/item?id=CML_2016__8_1_165_0> © Les auteurs et Confluentes Mathematici, 2016. Tous droits réservés. L’accès aux articles de la revue « Confluentes Mathematici » (http://cml.cedram.org/), implique l’accord avec les condi- tions générales d’utilisation (http://cml.cedram.org/legal/). Toute reproduction en tout ou partie de cet article sous quelque forme que ce soit pour tout usage autre que l’utilisation á fin strictement personnelle du copiste est constitutive d’une infrac- tion pénale. Toute copie ou impression de ce fichier doit contenir la présente mention de copyright. cedram Article mis en ligne dans le cadre du Centre de diffusion des revues académiques de mathématiques http://www.cedram.org/ Confluentes Math. 8, 1 (2016) 165-174 A SHORT PROOF OF UNIQUE ERGODICITY OF HOROSPHERICAL FOLIATIONS ON INFINITE VOLUME HYPERBOLIC MANIFOLDS BARBARA SCHAPIRA Abstract. We provide a new proof of the fact that the horospherical group N < G = SOo(d, 1) acting on the frame bundle Γ\G of a hyperbolic manifold admits a unique invariant ergodic measure (up to multiplicative constants) supported on the set of frames whose orbit under the geodesic flow comes back infinitely often in a compact set. This result is known, but our proof is more direct and much shorter. 1. Introduction The (unstable) horocycle flow on the unit tangent bundle of compact hyperbolic surfaces is uniquely ergodic. Furstenberg [6] proved that the Liouville measure is the unique invariant measure under this flow. -

Commensurability of Hyperbolic Manifolds with Geodesic Boundary

Commensurability of hyperbolic manifolds with geodesic boundary Roberto Frigerio∗ September 24, 2018 Abstract Suppose n > 3, let M1,M2 be n-dimensional connected complete finite- volume hyperbolic manifolds with non-empty geodesic boundary, and suppose that π1(M1) is quasi-isometric to π1(M2) (with respect to the word metric). Also suppose that if n = 3, then ∂M1 and ∂M2 are compact. We show that M1 is commensurable with M2. Moreover, we show that there exist homotopically equivalent hyperbolic 3-manifolds with non-compact geodesic boundary which are not commensurable with each other. We also prove that if M is as M1 above and G is a finitely generated group which is quasi-isometric to π1(M), then there exists a hyperbolic manifold with geodesic boundary M ′ with the following properties: M ′ is commensurable with ′ M, and G is a finite extension of a group which contains π1(M ) as a finite-index subgroup. MSC (2000): 20F65 (primary), 30C65, 57N16 (secondary). Keywords: Fundamental group, Cayley graph, Quasi-isometry, Quasi-conformal homeomorphism, Hyperbolic manifold. A quasi-isometry between metric spaces is a (not necessarily continuous) map which looks biLipschitz from afar (see Section 1 for a precise definition). Even if they do arXiv:math/0502209v1 [math.GT] 10 Feb 2005 not give information about the local structure of metric spaces, quasi-isometries usually capture the most important properties of their large-scale geometry. Let Γ be any group with a finite set S of generators. Then a locally finite graph is defined which depends on Γ and S (such a graph is called a Cayley graph of Γ, see Section 1).