And Others TITLE Community Human Resources Development in the Rehabilitation of the Handicapped

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Marriage of True Minds

THE MARRIAGE OF TRUE MINDS Of the Rise and Fall of the Idealized Conception of Friendship in the Renaissance Von der Gemeinsamen Fakultät für Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Hannover zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Dissertation von ROBIN HODGSON, M. A., geboren am 21.06.1969 in Neustadt in Holstein 2003 Referent: Prof. Dr. Gerd Birkner Korreferenten: Prof. Dr. Dirk Hoeges Prof. Dr. Beate Wagner-Hasel Tag der Promotion: 30.10.2003 ABSTRACT (DEUTSCH) Gegenstand der vorliegenden Untersuchung ist der Freundschaftsbegriff der Renaissance, der seinen Ursprung wesentlich in der antiken Philosophie hat, seine Darstellungsweisen in der europäischen (insbesondere der englischen und italienischen) Literatur des fünfzehnten und sechzehnten Jahrhunderts, und der Wandel, dem dieser beim Epochenwechsel zur Aufklärung im siebzehnten Jahrhundert unterworfen war. Meine Arbeit vertritt die Hypothese, dass sich die Konzeptionen der verschiedenen Formen zwischenmenschlicher Beziehung die sich spätestens seit dem achtzehnten Jahrhundert etablieren konnten, auf die konzeptionellen Veränderungen des Freund- schaftsbegriffs und insbesondere auf den Wandel des Begriffsverständnisses von Freundschaft und Liebe während der Renaissance und des sich anschließenden Epochenwechsels zurückführen lassen. Um diese Hypothese zu verifizieren, habe ich daher nach einer kurzen Übersicht über die konzeptionellen Ursprünge des frühneuzeitlichen Freundschaftsbegriffs zunächst das Wesen der primär auf den philosophischen -

Indianapolis Meeting of IU Board of Trustees

Tax form a ‘foreign language’ y y m m i caaraagreromllMlSsaup provide free m Mm c i If you have qusstiom concerning the It * n Great u> me. Waa thi Upon audit, the tonne* includes going with the client lo the federal return the local IRS hot n ammtance Rmt- m MM by Mi mobility to l^ reel Revenue Service exolauuna how the return w prepored and if the mu Lake u on the port of the preparer thr 1 OSSA or the ITto before April IS a hke trying to mtvk« include* paying internet end penalty charge* (hrected to Taxpayer Assistance UJ44U or to the totl free Both Block and Beneficial representatives suggest that they °r**4r U tH b U p ' con aave the average single person or mamed couple money Ado the federal government has published an assistance Fm a price tax service* ouch as H A R Bloek and B en***1 b*auoe of their knowledge regarding current deductions not guide entitled Tour Federal Income Tax For Use in Preparing m aw Tax Services will preparr thr return* far y » recognised by the average taxpayer 1979 Return for Individuals You can pick up the publication at on thr complexity of the return the amount « Fof tho»* <* you who are more ambitious and deodr to the local IRS office or call ShttOO and have them send it ' ask ition charge pr***xV y°Mr men return sUle and federal revenue agencies for it by name and number 17) Students to picket Indianapolis meeting of IU Board of Trustees bv ( artls M ria a irti justify their curreot investment line will be the first such action at policy IUPUI Student opponents of South Afnca s But despite the progressive force The picket line is to be peaceful ano apartheid system are organizing a argument s wide variety of groups legal according to ISAC and tht picket line outside the March 3 and individuals have voiced their protestor* w ill not try to prevent at maeting of the II Board of Trustees opposition ta corporate mvolvemeoi disrupt the Trustee s meeting scheduled to take place in the Union in South Afnca including I S Senator Following the picket liar there will ta Building nn the IlTUl campus Dick Clark. -

Name Artist Album Track Number Track Count Year Wasted Words

Name Artist Album Track Number Track Count Year Wasted Words Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 1 7 1973 Ramblin' Man Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 2 7 1973 Come and Go Blues Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 3 7 1973 Jelly Jelly Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 4 7 1973 Southbound Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 5 7 1973 Jessica Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 6 7 1973 Pony Boy Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 7 7 1973 Trouble No More Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 1 6 1972 Stand Back Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 2 6 1972 One Way Out Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 3 6 1972 Melissa Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 4 6 1972 Blue Sky Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 5 6 1972 Blue Sky Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 5 6 1972 Ain't Wastin' Time No More Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 6 6 1972 Oklahoma Hills Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 1 6 1969 Every Hand in the Land Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 2 6 1969 Coming in to Los Angeles Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 3 6 1969 Stealin' Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 4 6 1969 My Front Pages Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 5 6 1969 Running Down the Road Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 6 6 1969 I Believe When I Fall in Love Art Garfunkel Breakaway 1 8 1975 My Little Town Art Garfunkel Breakaway 1 8 1975 Ragdoll Art Garfunkel Breakaway 2 8 1975 Breakaway Art Garfunkel Breakaway 3 8 1975 Disney Girls Art Garfunkel Breakaway 4 8 1975 Waters of March Art Garfunkel Breakaway 5 8 1975 I Only Have Eyes for You Art Garfunkel Breakaway 7 8 1975 Lookin' for the Right One Art Garfunkel Breakaway 8 8 1975 My Maria B. -

RCA Consolidated Series, Continued

RCA Discography Part 18 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Consolidated Series, Continued 2500 RCA Red Seal ARL 1 2501 – The Romantic Flute Volume 2 – Jean-Pierre Rampal [1977] (Doppler) Concerto In D Minor For 2 Flutes And Orchestra (With Andraìs Adorjaìn, Flute)/(Romberg) Concerto For Flute And Orchestra, Op. 17 2502 CPL 1 2503 – Chet Atkins Volume 1, A Legendary Performer – Chet Atkins [1977] Ain’tcha Tired of Makin’ Me Blue/I’ve Been Working on the Guitar/Barber Shop Rag/Chinatown, My Chinatown/Oh! By Jingo! Oh! By Gee!/Tiger Rag//Jitterbug Waltz/A Little Bit of Blues/How’s the World Treating You/Medley: In the Pines, Wildwood Flower, On Top of Old Smokey/Michelle/Chet’s Tune APL 1 2504 – A Legendary Performer – Jimmie Rodgers [1977] Sleep Baby Sleep/Blue Yodel #1 ("T" For Texas)/In The Jailhouse Now #2/Ben Dewberry's Final Run/You And My Old Guitar/Whippin' That Old T.B./T.B. Blues/Mule Skinner Blues (Blue Yodel #8)/Old Love Letters (Bring Memories Of You)/Home Call 2505-2509 (no information) APL 1 2510 – No Place to Fall – Steve Young [1978] No Place To Fall/Montgomery In The Rain/Dreamer/Always Loving You/Drift Away/Seven Bridges Road/I Closed My Heart's Door/Don't Think Twice, It's All Right/I Can't Sleep/I've Got The Same Old Blues 2511-2514 (no information) Grunt DXL 1 2515 – Earth – Jefferson Starship [1978] Love Too Good/Count On Me/Take Your Time/Crazy Feelin'/Crazy Feeling/Skateboard/Fire/Show Yourself/Runaway/All Nite Long/All Night Long APL 1 2516 – East Bound and Down – Jerry -

Jefferson Starship Red Octopus Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jefferson Starship Red Octopus mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Red Octopus Country: US Released: 1975 Style: Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1747 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1921 mb WMA version RAR size: 1167 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 963 Other Formats: VOC MIDI WAV AHX VOX DMF WMA Tracklist Hide Credits Fast Buck Freddie A1 3:28 Bass – Pete*Lyrics By – Grace SlickMusic By – Craig ChaquicoPiano – David* Miracles A2 6:52 Bass, Electric Piano – Pete*Organ – David*Written-By – Marty Balin Git Fiddler A3 3:08 Bass – David*Keyboards – Pete*Written-By – John Parker*, Kevin Moore , John Creach* Ai Garimasu (There Is Love) A4 Bass – Pete*Music By – Grace SlickPiano – Grace*Synthesizer [Arp] – David*Written-By – 4:15 Grace Slick Sweeter Than Honey A5 Bass, Keyboards – Pete*Lyrics By – Craig Chaquico, Marty BalinMusic By – Craig Chaquico, 3:20 Pete Sears Play On Love B1 3:44 Bass – David*Lyrics By – Grace SlickMusic By – Pete SearsPiano, Organ, Clavinet – Pete* Tumblin B2 Bass – Pete*Keyboards – David*Lyrics By – Marty Balin, Robert HunterMusic By – David 3:27 Freiberg I Want To See Another World B3 Lyrics By – Grace Slick, Marty Balin, Paul KantnerMusic By – Paul KantnerOrgan – 4:34 David*Piano, Bass, Organ – Pete* Sandalphon B4 4:08 Bass – David*Music By – Pete SearsSynthesizer [Arp], Piano, Organ – Pete* There Will Be Love B5 Bass – Pete*Lyrics By – Marty Balin, Paul KantnerMusic By – Craig Chaquico, Paul 5:04 KantnerSynthesizer [Amp] – David* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Grunt Manufactured By – RCA Records Distributed By – RCA Records Recorded At – Wally Heider Studios Mixed At – Wally Heider Studios Mastered At – Kendun Recorders Published By – Ronin Music Published By – Lunatunes Published By – Diamondback Music Co. -

Success Story E-Mag June 2008 (About Talented Cameroonians At

About Talented Cameroonians at Home and Abroad N° 010 JUNE 2008 Les NUBIANS Sam Fan Thomas Ekambi Brillant Salle John Jacky Biho Majoie Ayi Prince Nico Mbarga BENGA Martin Directeur Général elcome, my Dear Readers to the 10th Issue of your favourite E-Magazine that brings talented Cameroonians every month to your Desktop. W In this colourful Issue, we take you into the world of Cameroonian Music to meet those talented ladies and gentlemen whose voices and rhythms have kept us dancing and singing for generations. Every Cameroonian has his/her own daily repertoire of Cameroonian hits that he/she hums all day at work, at home, at school and other places. Over the radio, on TV and the internet, we watch our talented musicians spill off traditional rhythms that have been modernized to keep us proud of more than 240 tribes from ten provinces that make up Cameroon. For a start, let’s take you to Tsinga Yaounde to watch Ekambi Brillant, Jacky Biho, Salle John and Sam Fan Thomas on stage at Chez Liza et Christopher. To get a touch of world music we go to France to watch Les Nubians. We return to Yaounde to join Ottou Marcelin, Ateh Bazor, Le- Doux Marcellin, Patou Bass, Atango de Manadjama, Majoie Ayi, LaRosy Akono and several others to celebrate the World Music Day in a live con- cert that was organised by CRTV FM94 on June 21 2008 at the May 20 Boulevard. How many music genres are there in Cameroon? We attempt to answer that question by taking you around, in a world of rhythms that you know so well: makossa, bikutsi, zingué, ambassbay, bendskin, bottledance, assiko, tchamassi, makassi, Zeke Zeke and hope to see you dancing while you go through our attempt to explain their origins and present their promoters. -

The Representation of Gender and the Construction of the Female Self in Shakespeare´S Crossdressing Comedies

The Representation of Gender and the Construction of the Female Self in Shakespeare´s Crossdressing Comedies Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Magistra der Philosophie vorgelegt von Christina Elisabeth Weichselbaumer 1311151 am Institut für: Anglistik Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. phil. Martin Löschnigg Graz, Dezember 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I want to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis advisor Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. phil. Martin Löschnigg, who has been supportive in so many ways since the moment I started writing the first page. He had a sympathetic ear for all my questions or concerns and his office door was always open for me to drop in and start discussing some aspects of my writing. – Thank you for your patience! I would also like to thank the team of the Globe Library and Archive in London for granting me access to archive material and assisting me in my research. The costume bibles in particular proved to be very helpful. I also would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Clare McManus who has initially fuelled my interest in gender studies and the conception of early modern femininity. In addition, I would like to thank my former teachers Mag. Werner Pleschberger and Mag. Liselotte Keller for having stirred my enthusiasm and love for reading and literature. Besides, I am deeply grateful for George Kiernan´s contribution of proof-reading my thesis so thoroughly and quickly. Many other friends have read the manuscript, given me feedback and supported my work in important ways. I am indebted to all of you. -

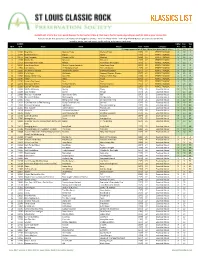

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

Vintage Voice

A Blast from Voices Past Dealing with Writer’s Block Possessed by Language October 27, 2017 Volume 25, Issue 42 1 The Voice’s interactive Table of Contents allows you to click a story title to jump to an article. Clicking the bottom right CONTENTS corner of any page returns you here. Some ads and graphics are also links. Features Blast from Voices Past ................................................ 4 Articles Editorial: Grand Opening Special .......................................................... 3 Fly on the Wall: Possessed by Language! ............................................ 6 Dealing with Writer’s Block Effectively(ish) ....................................... 21 Columns The Not-So-Starving Student: Spooky Cocktails ................................. 9 In Conversation: with Sierra Blanca .................................................... 11 The Fit Student: Double-Double Trouble ............................................ 15 The Study Dude: Word Lust ................................................................. 17 Dear Barb: Thanksgiving Unwelcome ................................................. 22 News and Events AU-Thentic Events ............................................................................... 7,8 Canadian Science News ...................................................................... 13 Scholarship of the Week ...................................................................... 16 Canadian Education News .................................................................. 18 Women of Interest ............................................................................... -

RCA Victor Consolidated Series

RCA Discography Part 17 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor Consolidated Series In 1972, RCA instituted a consolidated series, where all RCA releases were in the same series, including albums that were released on labels distributed by RCA. APL 1 0001/APD 1 0001 Quad/APT 1 0001 Quad tape — Love Theme From The Godfather — Hugo Montenegro [1972] Medley: Baby Elephant Walk, Moon River/Norwegian Wood/Air on the G String/Quadimondo/I Feel the Earth Move/The Godfather Waltz/Love Theme from the Godfather/Pavanne/Stutterolgy RCA Canada KPL 1 0002 — Trendsetter — George Hamilton IV [1975] Canadian LP. Bad News/The Ways Of A Country Girl/Let My Love Shine/Where Would I Be Now/The Good Side Of Tomorrow/My Canadian Maid/The Wrong Side Of Her Door/Time's Run Out On You/The Isle Of St. Jean/The Dutchman RCA Red Seal ARL 1 0002/ARD 1 0002 Quad – The Fantastic Philadelphians Volume 1 – Eugene Ormandy and Philadelphia Orchestra [1972] EspanÞa Rhapsody (Chabrier)/The Sorcerer's Apprentice (Dukas)//Danse Macabre (Saint-Sae8ns)/A Night On Bald Mountain (Moussorgsky) 0003-0007 (no information) RCA Special Products DPL 1 0008 – Toyota Jazz Parade – Various Artists [1973] Theme from Toyota – Al Hirt/Java – Al Hirt/Cotton Candy – Al Hirt/When the Saints Go Marching In – Al Hirt/At the Jazz Band Ball – Dukes of Dixieland/St. Louis Blues – Louis Armstrong/St. James Infirmary – King Oliver//Hi-Heel Sneakers – Jose Feliciano/Amos Moses – Jerry Reed/Theme from Shaft – Generation Gap/Laughing – Guess Who/Somebody to Love – Jefferson Airplane 0009-0012 (no information) APL 1 0013/APD 1 0013 Quad/APT 1 0013 Quad tape — Mancini Salutes Sousa — Henry Mancini [1972] Drum Corps/Semper Fidelis/Washington Post/Drum Corps/King Cotton/National Fencibles/The Thunderer/Drum Corps/El Capitan/The U. -

Foregrounding the Background: Images of Dutch and Flemish Household Servants

chapter 7 Foregrounding the Background: Images of Dutch and Flemish Household Servants Diane Wolfthal To a great extent, art historians who study early modern women have focused on what Patricia Skinner has termed “the great and the good”: aristocratic women, wives of wealthy merchants, and female artists, saints, and nuns.1 Not only do publications privilege these groups, but so do titles of paintings that were invented in the modern era. Such titles as Lady at her Toilette, Young Woman with a Pearl Necklace, or Man Visiting a Woman Washing her Hands disregard the presence of the working-class women in the compositions (Figs. 7.1–7.2).2 This essay instead explores a group that art historians have largely ignored: ordinary female household servants. Although several historians have focused on seventeenth-century Dutch servants, few art historians have discussed them, and, other than Bert Watteeuw’s recent essay on Rubens’ domestic staff, house- hold workers from the Southern Netherlands or from earlier centuries have been largely overlooked.3 The reasons for this are numerous. Few documents 1 Patricia Skinner’s phrase derives from her paper, “The medieval female life cycle as an organizing strategy,” presented at “Gender and Medieval Studies Annual Conference: Gender, Time and Memory,” Swansea University, 6 January 2011–8 January 2011. I would like to thank Amanda Pipkin and Sarah Moran for inviting me to speak at the conference Concerning Early Modern Women of the Low Countries and for their helpful bibliographical suggestions and thoughtful comments and on earlier drafts of this essay. 2 See, among others, Otto Nauman, “Frans van Mieris’s Personal Style,” in Frans van Mieris 1635– 1681, ed. -

Nters Sisters

SEI 13 $1.95 nters Sisters www.americanradiohistory.com TAKE A .H T' Contains Ten Classic Soes From America's Premier Rock'n'roll G "Ride The Tiger" "Caroline" "Play On Love" "Miracles" "Fast Buck Freddie" "With Your Love" "St. Charles" "Count On Me" "Love Too Good" "Runaway" Also Includes Free Bonus Single: "Light The Sky On Fire" b/w "Hyperdrive" Produced by Larry Cox and Jefferson Sfarship (Not Available On Any Album) Manager Bill Thompson Marrulaclurert ana n, RCA Rer nrn www.americanradiohistory.com VOLUME XL - NUMBER 37 - January 27, 1979 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC RECORD WEEKLY COSH BOX GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher The Age Of The Superpowers MEL ALBERT EDITORIAL Vice President and General Manager CHUCK MEYER The era of the superpowers in the record industry the '50s when Columbia, Mercury, Decca and RCA Director of Marketing is upon us. With the move by A&M to RCA for dis- monopolized the charts. Then, rock 'n' roll appeared DAVE FULTON tribution, amid indications still more indie labels are and the structure went through a transition, only to Editor In Chief about to opt for branch set ups, it appears that a end up in a similar position today. J.B. CARMICLE handful of multinational corporations are the en- There will always be an opportunity for the General Manager, East Coast tities to watch in the business. aggressive individualist in the industry, because it is JIM SHARP CBS, WEA, RCA, Polygram, EMI and MCA. These a creative business dependent upon creative peo- Director, Nashville are the firms that have divided up the pie and will ple.