Analysis of Richard Brautigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Non Blondes What's up Abba Medley Mama

4 Non Blondes What's Up Abba Medley Mama Mia, Waterloo Abba Does Your Mother Know Adam Lambert Soaked Adam Lambert What Do You Want From Me Adele Million Years Ago Adele Someone Like You Adele Skyfall Adele Turning Tables Adele Love Song Adele Make You Feel My Love Aladdin A Whole New World Alan Silvestri Forrest Gump Alanis Morissette Ironic Alex Clare I won't Let You Down Alice Cooper Poison Amy MacDonald This Is The Life Amy Winehouse Valerie Andreas Bourani Auf Uns Andreas Gabalier Amoi seng ma uns wieder AnnenMayKantenreit Barfuß am Klavier AnnenMayKantenreit Oft Gefragt Audrey Hepburn Moonriver Avicii Addicted To You Avicii The Nights Axwell Ingrosso More Than You Know Barry Manilow When Will I Hold You Again Bastille Pompeii Bastille Weight Of Living Pt2 BeeGees How Deep Is Your Love Beatles Lady Madonna Beatles Something Beatles Michelle Beatles Blackbird Beatles All My Loving Beatles Can't Buy Me Love Beatles Hey Jude Beatles Yesterday Beatles And I Love Her Beatles Help Beatles Let It Be Beatles You've Got To Hide Your Love Away Ben E King Stand By Me Bill Withers Just The Two Of Us Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Billy Joel Piano Man Billy Joel Honesty Billy Joel Souvenier Billy Joel She's Always A Woman Billy Joel She's Got a Way Billy Joel Captain Jack Billy Joel Vienna Billy Joel My Life Billy Joel Only The Good Die Young Billy Joel Just The Way You Are Billy Joel New York State Of Mind Birdy Skinny Love Birdy People Help The People Birdy Words as a Weapon Bob Marley Redemption Song Bob Dylan Knocking On Heaven's Door Bodo -

The Democratic Fiction of Richard Brautigan

tile, like an Italian restaurant’s, and the main room doubles as a gallery for MAN UNDERWATER the Clark County Historical Museum, which, on the day of my visit, featured The democratic !ction of Richard Brautigan an exhibit of Vancouver’s newspapers. The shop sells such dreary volumes as By Wes Enzinna For the Love of Farming and Weather of the Paci!c Northwest. The library is situated in a corner of Discussed in this essay: the museum and looks like a living room, with two stuffed chairs and an Jubilee Hitchhiker: The Life and Times of Richard Brautigan, by William end table facing a set of bookshelves. Hjortsberg. Counterpoint. 880 pages. $42.50. counterpointpress.com. A whitewashed sign announces that this is #$% &'()#*+(, -*&'('.: ( /%'. 0)&-*1 -*&'('., though there’s no one around except a tall man standing behind one of the chairs, who turns out to be a life-size card- board cutout of the late author Rich- ard Brautigan. Patrons from across the United States have paid twenty-!ve dollars apiece to house their unpub- lished novels here, books with titles like “Autobiography About a Nobody” and “Sterling Silver Cockroaches.” The shelves hold 291 of these cheap vinyl-bound volumes, which are orga- nized into categories according to a schema called the Mayonnaise System: Adventure, Natural World, Street Life, Family, Future, Humor, Love, War and Peace, Meaning of Life, Poetry, Spiri- tuality, Social/Political/Cultural, and All the Rest. Bylines and titles don’t appear on the covers. “The only way to browse the stacks is to choose a category and pick at random,” Barber explains. -

Big Sur for Other Uses, See Big Sur (Disambiguation)

www.caseylucius.com [email protected] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Big Sur For other uses, see Big Sur (disambiguation). Big Sur is a lightly populated region of the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries, many definitions of the area include the 90 miles (140 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County,[1][2] and extend about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. Other sources limit the eastern border to the coastal flanks of these mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland. Another practical definition of the region is the segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel south to San Simeon. The northern end of Big Sur is about 120 miles (190 km) south of San Francisco, and the southern end is approximately 245 miles (394 km) northwest of Los Angeles. The name "Big Sur" is derived from the original Spanish-language "el sur grande", meaning "the big south", or from "el país grande del sur", "the big country of the south". This name refers to its location south of the city of Monterey.[3] The terrain offers stunning views, making Big Sur a popular tourist destination. Big Sur's Cone Peak is the highest coastal mountain in the contiguous 48 states, ascending nearly a mile (5,155 feet/1571 m) above sea level, only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[4] The name Big Sur can also specifically refer to any of the small settlements in the region, including Posts, Lucia and Gorda; mail sent to most areas within the region must be addressed "Big Sur".[5] It also holds thousands of marathons each year. -

A History of the Communication Company, 1966-1967

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Summer 2012 Outrageous Pamphleteers: A History Of The Communication Company, 1966-1967 Evan Edwin Carlson San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Carlson, Evan Edwin, "Outrageous Pamphleteers: A History Of The Communication Company, 1966-1967" (2012). Master's Theses. 4188. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.cg2e-dkv9 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4188 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OUTRAGEOUS PAMPHLETEERS: A HISTORY OF THE COMMUNICATION COMPANY, 1966-1967 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Library and Information Science San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Library and Information Science by Evan E. Carlson August 2012 © 2012 Evan E. Carlson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled OUTRAGEOUS PAMPHLETEERS: A HISTORY OF THE COMMUNICATION COMPANY, 1966-1967 by Evan E. Carlson APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY August 2012 Dr. Debra Hansen School of Library and Information Science Dr. Judith Weedman School of Library and Information Science Beth Wrenn-Estes School of Library and Information Science ABSTRACT OUTRAGEOUS PAMPHLETEERS: A HISTORY OF THE COMMUNICATION COMPANY, 1966-1967 by Evan E. -

Song List 10'S 00'S 90'S 80'S 70'S 50'S & 60'S Jazz

Song List 10’s 00’s 80’s 70’s Song Artist Song Artist Song Artist Song Artist 24K Magic Bruno Mars American Boy Estelle 9 to 5 Dolly Parton April Sun In Cuba Dragon All About That Bass Meghan Trainor Big Jet Plane Angus & Julia Stone All Night Long Lionel Richie Best of My Love Emotions Bad Guy Billie Eilish Buttons The Pussycat Dolls Better Be Home Soon Crowded House Blame It on The Boogie The Jacksons Be The One Dua Lipa Crazy In Love Beyonce Bette Davis Eyes Kim Carnes Dancing Queen ABBA Blinding Lights The Weeknd Crazy Gnarls Barkley Blister In The Sun Violent Femmes Dreams Fleetwood Mac Break Free Ariana Grande Don’t Know Why Norah Jones Call Me Blondie Eagle Rock Daddy Cool Break My Heart Dua Lipa Don’t Stop The Music Rihanna Crazy Little Thing Called Love Queen Go Your Own Way Fleetwood Mac Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen Forget You Cee Lo Green Do You See What I See Hunters & Collectors Highway To Hell ACDC Can’t Feel My Face The Weeknd Hot & Cold Katy Perry Don’t Stop Believin’ Journey I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor Can’t Hold Us Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Jai Ho Pussycat Dolls Easy Lionel Richie Let's Stay Together Al Green Cake By The Ocean DNCE Love Story Taylor Swift Feeling Hot Hot Hot The Merrymen Mamma Mia ABBA Can’t Stop The Feeling! Justin Timberlake Mr Brightside Killers Flame Trees Cold Chisel Moondance Van Morrison Cheap Thrills Sia Murder On The Dance Floor Sophie Ellis-Bextor Footloose Kenny Loggins Proud Mary Tina Turner Closer The Chainsmokers Party In The U.S.A Miley Cyrus Free Fallin’ Tom Petty Rock With You Michael -

Wind Bell

PUBLICATION OF ZEN CENTER Volume Yll Nos. 3-4 Fall 1968 Last summer Zen Center was at a critical stage in its evolution. The numerous changes resulting from the advent of Zen Mountain Center needed to be consolidated into a satisfactory and stable teaching situation for Suzuki Roshi and the stu· dents. Zen Center found that a number of do0nors were willing to contribute for the specific purpose of freeing the studenrs from the pressures of fund-raising so that they could concentrate on continuing the development of Zen Center and Zen Mountain Center. Nearly S65,000 was donai;. ed. This amount was turned over to Bob and Anna Beck, the previous owners of Tassajara, to cover the next three payments. In return they reduced the final purchase price. Zen Center will now be able to diminish the expe!llse and energy drain of two fund-raising drives a year and direct its funding activities in a more: balanced way. It is hoped that enough will be donated in an annual drive early each fa!ll to secure the following December and March pay ments in advance. However, if you had plamned to make a contribution towards this December's payment, please do. S12,000 in personal loans is already overdue and Sl04,000 is still owed on the Zen Mountain Center land. Why one should help cannot be easily exp[ain· ed. There may not be any personal benefit derived from doing so. In the Diamond Sutra Buddha asks: "What do you think, Subhuti, if a son or daughter of good family had filled this world system of a 1,000 million worlds with the seven precious things, and then gave it as a gift to the Tathagatas, the Arl1ats, t.he Fully Enlightened Ones, would they on the strength of that beget a great heap of merit?" Subhuti replied: "They would, 0 Lord, they would, 0 Well Gone! But if, ot1 the other hand, there were such a thing as a heap of merit, the Tathagata would not have spoken of a heap of merit." The lllmperor of China asked a similar ~ uestion of Bodhidharma: "Since 1 ascended the throne," began the Emperor, "I have erected numeroi<s temples. -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

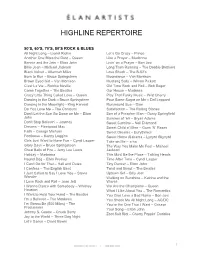

Highline Repertoire

HIGHLINE REPERTOIRE 50’S, 60’S, 70’S, 80’S ROCK & BLUES All Night Long – Lionel Richie Let’s Go Crazy – Prince Another One Bites the Dust – Queen Like a Prayer – Madonna Bennie and the Jets – Elton John Livin’ on a Prayer – Bon Jovi Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Long Train Running – The Doobie Brothers Black Velvet – Allannah Miles Love Shack – The B-52’s Born to Run – Bruce Springsteen Moondance – Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Mustang Sally – Wilson Pickett C’est La Vie – Robbie Neville Old Time Rock and Roll – Bob Seger Come Together – The Beatles Our House – Madness Crazy Little Thing Called Love – Queen Play That Funky Music – Wild Cherry Dancing in the Dark – Bruce Springsteen Pour Some Sugar on Me – Def Leppard Dancing in the Moonlight – King Harvest Runaround Sue – Dion Do You Love Me – The Contours Satisfaction – The Rolling Stones Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me – Elton Son of a Preacher Man – Dusty Springfield John Summer of ’69 – Bryan Adams Don’t Stop Believin’ – Journey Sweet Caroline – Neil Diamond Dreams – Fleetwood Mac Sweet Child o’ Mine – Guns ‘N’ Roses Faith – George Michael Sweet Dreams – Eurythmics Footloose – Kenny Loggins Sweet Home Alabama – Lynyrd Skynyrd Girls Just Want to Have Fun – Cyndi Lauper Take on Me – a-ha Glory Days – Bruce Springsteen The Way You Make Me Feel – Michael Great Balls of Fire – Jerry Lee Lewis Jackson Holiday – Madonna This Must Be the Place – Talking Heads Hound Dog – Elvis Presley Time After Time – Cyndi Lauper I Can’t Go for That – Hall and Oates Tiny Dancer – Elton John -

The Connection Song List

THE CONNECTION SONG LIST Thank you for downloading our song list! Which specific songs we perform at any given event is based on 3 factors: 1) Popular music that will create an unforgettable party. We “read” your crowd and all the age groups in attendance, calling songs accordingly. 2) General musical styles that fit into your personal preferences. 3) What we perform best; songs that help to make us who we are. We don’t work with pre-determined set lists, but we will try to include many of your preferences & favorites. This in addition to you choosing all the material for any formal dances. We’ll also learn two new songs for you that are not a regular part of our repertoire! (formal dances take precedence). Top 40 Song Title Artist Silk Sonic Leave The Door Open The Weeknd Blinding Lights Lady Gaga, Ariana Grande Rain On Me Kygo & Whitney Houston Higher Love Harry Styles Watermelon Sugar Dua Lipa Don't Start Now Lizzo Juice Lizzo Truth Hurts Lil NasX ft. Billy Ray Cyrus Old Town Road Jonas Brothers Sucker The Blackout Allstars / Cardi B I Like It Like That Lady Gaga & Bradley Cooper Shallow Zedd, Maren Morris, Grey The Middle Luis Fonsi Despacito Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars That's What I Like Bruno Mars Ft. Cardi B Finesse Camila Cabello Havana Dua Lipa, Calvin Harris One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Ed Sheeran Shape Of You Shawn Mendes There's Nothing Holding Me Back Clean Bandit Rockabye Niall Horan Slow Hands Sia Cheap Thrills Ariana Grande Thank U, Next Drake One Dance The Chainsmokers Closer -

August 7, 2015 Opening Reception: Thursday, June 25, 6 – 8 PM

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE All Watched Over curated by Tina Kukielski June 25 – August 7, 2015 Opening Reception: Thursday, June 25, 6 – 8 PM BRENNA MURPHY sunriseSequence~inlet, 2015 archival pigment print Courtesy of American Medium, Brooklyn, NY James Cohan Gallery is pleased to present a group exhibition curated by Tina Kukielski entitled All Watched Over, opening on June 25th, 2015 and running through August 7th, 2015. Richard Brautigan’s poem All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, written in 1967 while he was poet-in-residence at the California Institute of Technology, anticipates an ecosystem where animal, human, and machine live in harmony with nature. Freed from the constraints of labor and balanced by cybernetic feedback mechanisms that regulate and sustain life, the humans in Brautigan’s short poem flourish in a naturalistic techno-utopia. Years later, acclaimed documentary journalist Adam Curtis appropriated Brautigan’s title when he aired a BBC television series under the same name in 2011. From the standpoint of the recent past, Curtis’s wide-reaching documentary analyses the vicissitudes of the postmodern techno-utopia Brautigan alludes to in his poem. In his signature style, Curtis argues that computers have failed to be the great liberators they were once purported to be. With the promise of a cybernetic techno-utopia as its backdrop, this exhibition brings together a group of artists who apply systems to and in their work. Across a diversity of practices and cultures, the dominant theme in All Watched Over is art in the form of information processing and its diagramming. Set against today’s data-processed landscape, the artworks in All Watched Over transform data into hidden messages, ciphers, unifying theories, complex diagrams, and personal or cultural cosmologies. -

Schedule Quickprint TKRN-FM

Schedule QuickPrint TKRN-FM 5/31/2021 7PM through 5/31/2021 11P s: AirTime s: Runtime Schedule: Description 07:00:00p 00:00 Monday, May 31, 2021 7PM 07:00:00p 02:58 DON'T START NOW / DUA LIPA 07:02:58p 03:32 WE BELONG / PAT BENATAR 07:06:30p 03:28 BEFORE YOU GO / LEWIS CAPALDI 07:09:58p 03:58 S.O.S. (RESCUE ME) / RIHANNA 07:13:56p 03:24 ADORE YOU / HARRY STYLES 07:17:20p 04:39 IRIS / GOO GOO DOLLS 07:21:59p 03:35 LEAVE THE DOOR OPEN / BRUNO MARS/ANDERSON PAAK/SILK SONIC 07:25:34p 02:38 FEEL IT STILL / PORTUGAL THE MAN 07:28:16p 03:30 STOP-SET 07:35:03p 02:58 SUCKER / JONAS BROTHERS 07:38:01p 03:58 SOMETHING JUST LIKE THIS / CHAINSMOKERS & COLDPLAY 07:41:59p 04:21 PAPA DON'T PREACH / MADONNA 07:46:20p 02:43 YOU BROKE ME FIRST / TATE MC RAE 07:49:03p 03:20 MOVES LIKE JAGGER / MAROON 5 FETURING CHRISTINA AGUILERA 07:52:23p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:00:00p 00:00 Monday, May 31, 2021 8PM 08:00:00p 03:28 CIRCLES / POST MALONE 08:03:28p 04:00 HEAVEN IS A PLACE ON EARTH / BELINDA CARLISLE 08:07:28p 03:09 MOOD (MIXSHOW EDIT CLEAN) / 24KGOLDN 08:10:37p 03:52 IT'S TIME / IMAGINE DRAGONS 08:14:29p 03:31 SOMEONE TO YOU / BANNERS 08:18:00p 03:43 IT MUST HAVE BEEN LOVE / ROXETTE 08:21:43p 03:38 BREAK MY HEART / DUA LIPA 08:25:21p 03:24 ATTENTION / CHARLIE PUTH 08:28:49p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:35:36p 03:00 SAVAGE LOVE / JAWSH 365 X JASON DERULO X BTS 08:38:36p 03:21 USE SOMEBODY / KINGS OF LEON 08:41:57p 03:42 THE TIDE IS HIGH / BLONDIE 08:45:39p 02:47 THEREFORE I AM / BILLIE EILESH 08:48:26p 04:00 WAKE ME UP / AVICII 08:52:26p 03:30 STOP-SET 09:00:00p 00:00 Monday, -

Richard Brautigan During the Week of April 9-13 Poet-Author Richard Brautigan Will Bring His Deeds to the MSU Campus and the Bozeman Community

Harrisburg incident sparks anti-nuke protests (UPI) Anti-nuclear protestors grave radiation leak accident in crisp, 50-degree weather for a Consumer advocate Ralph Georgians Against Nuc lear around the nation and in Japan the United States. Immediately peaceful protest, listening to anti Nader addressed the group, Energy rally. Meanwhile, aoout Sunday demanded a moratoriwn suspend all nuclear power nuclear speeches and songs. calling the American nuclear 75 University of Georgia students on nuclear power and the shut generation for the survival of all However, President Carter was power plant program " this marched in the rain from the down of the crippled Three Mile life on earth," a streamer read. at Camp David Sunday. technological Vietnam. Again Athens Georgia power office to Island, Pa., plant or similar The sit-in ended in silent In California, about 7 ,000 and again this form of pernicious the steps of city hall, protesting facilities in their areas. prayers in memory of the persons marched in front of the energy has proved far too the rails shipments of nuclear More than 150 Hiroshima estimated 80,000 persons killed in San Franciso city hall to catastrophic, far too expensive •.....•.............••.....waste through Athens. atomic bomb victims and their August 1945 when American denounce a Pacific Gas and and far too unreliable to have a . supporters staged a sit-in at the planes dropped the world's first Electric Co., nuclear power plant place in the future of this coun : Brautigan at MSU Hiroshima Peace Park in Tokyo atomic bomb. scheduled to start operation this try," Nader said.