Teaching History Through Entertainment: the Pedagogy of Who Do You Think You Are?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siff Announces Full Lineup for 40Th Seattle

5/1/2014 ***FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE*** Full Lineup Announced for 40th Seattle International Film Festival FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact, SIFF Rachel Eggers, PR Manager [email protected] | 206.315.0683 Contact Info for Publication Seattle International Film Festival www.siff.net | 206.464.5830 SIFF ANNOUNCES FULL LINEUP FOR 40TH SEATTLE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Elisabeth Moss & Mark Duplass in "The One I Love" to Close Fest Quincy Jones to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award Director Richard Linklater to attend screening of "Boyhood" 44 World, 30 North American, and 14 US premieres Films in competition announced SEATTLE -- April 30, 2014 -- Seattle International Film Festival, the largest and most highly attended festival in the United States, announced today the complete lineup of films and events for the 40th annual Festival (May 15 - June 8, 2014). This year, SIFF will screen 440 films: 198 features (plus 4 secret films), 60 documentaries, 14 archival films, and 168 shorts, representing 83 countries. The films include 44 World premieres (20 features, 24 shorts), 30 North American premieres (22 features, 8 shorts), and 14 US premieres (8 features, 6 shorts). The Festival will open with the previously announced screening of JIMI: All Is By My Side, the Hendrix biopic starring Outkast's André Benjamin from John Ridley, Oscar®-winning screenwriter of 12 Years a Slave, and close with Charlie McDowell's twisted romantic comedy The One I Love, produced by Seattle's Mel Eslyn and starring Elisabeth Moss and Mark Duplass. In addition, legendary producer and Seattle native Quincy Jones will be presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the screening of doc Keep on Keepin' On. -

Star-Studded Line-Up Set for the 7Th AACTA Awards Presented by Foxtel

Media Release Strictly embargoed until 12:01am Wednesday 22 November 2017 Star-studded line-up set for the 7th AACTA Awards presented by Foxtel The Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) has today announced the star-studded line- up of presenters and attendees of the 7th AACTA Awards Ceremony presented by Foxtel. Held at The Star Event Centre in Sydney on Wednesday 6 December and telecast on Channel 7, tickets are still available to enjoy a night of glamour and entertainment with the country’s biggest stars. Tickets are open to the public and industry and are selling fast. To book, visit www.aacta.org. The Ceremony will see some of Australia’s top film and television talent take to the stage to present, including: Jessica Marais, Rachel Griffiths, Bryan Brown, Charlie Pickering, Noni Hazlehurst, Shane Jacobson, Sophie Monk, Rob Collins, Samara Weaving, Daniel MacPherson, Tom Gleeson, Erik Thomson, Melina Vidler, Ryan Corr, Dan Wyllie and celebrated Indian actor and member of the Best Asian Film Grand Jury Anupam Kher. Nominees announced as presenters today include: Celia Pacquola, Pamela Rabe, Marta Dusseldorp, Stephen Curry, Emma Booth, Osamah Sami, Ewen Leslie and Sean Keenan. A number of Australia’s rising stars will also present at the AACTA Awards Ceremony, including: Angourie Rice, Nicholas Hamilton, Madeline Madden, and stars of the upcoming remake of STORM BOY, Finn Little and Morgana Davies. Last year’s Longford Lyell recipient Paul Hogan will attend the Ceremony alongside a number of this year’s nominees, including: Anthony LaPaglia, Shaynna Blaze, Luke McGregor, Don Hany, Jack Thompson, Kate McLennan, Sara West, Matt Nable, Jacqueline McKenzie and Susie Porter. -

Legal Forum to Spotlight Fraud, Scam Activity by RICK NORTON Library in Conjunction with the Bradley Division of Consumer Affairs; Rachel Seating Is Still Available

W E D N E S D A Y 161st yEAR • No. 280 MARCH 23, 2016 ClEVElAND, tN 26 PAGES • 50¢ Legal forum to spotlight fraud, scam activity By RICK NORTON Library in conjunction with the Bradley Division of Consumer Affairs; Rachel seating is still available. Associate Editor County Bar Association and the Bradley Powers, director of Policy and Development Depending on subject matter, the size of County Law Library Commission, the latest for the Division of Consumer Affairs of the past legal forum crowds has been moderate Scammers and fraudsters looking to take in the legal forum series will kick off at 7 Tennessee Department of Commerce and to heavy. Because this one involves the a chunk out of the wallets of Bradley County p.m. Insurance; and Sgt. Daniel Morton, repre- worsening wave of scam and fraud artistry, residents may find a bite being taken out of Jack Tapper, former president of the local senting the Identity Crimes Unit of the Tapper projects public response will be their own schemes with today’s announce- Bar Association who has coordinated the Tennessee Highway Patrol. strong. ment of the next Community Legal Forum. popular civic seminars since their 2010 As is the tradition surrounding the inter- This is the second time in three years the Compliments of an ongoing, three- inception, will again moderate the 90- active sessions, the coming forum is open to legal forums have spotlighted fraud. The pronged partnership, the coming forum — minute gathering while also serving as a the public with free admission. subject has resurfaced because of the grow- scheduled for next Thursday, March 31 — panelist. -

Book Industry Collaborative Council

FINAL REPORT 2 The material contained in this report has been developed by the Book Industry Collaborative Council. The views and opinions expressed in the materials do not necessarily reflect the views of or have the endorsement of the Australian Government or of any Minister, or indicate the Australian Government’s commitment to a particular course of action. The Australian Government accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents and accepts no liability in respect of the material contained in the report. ISBN: 978-1-921916-97-7 (web edition) Except for any material protected by a trade mark, and where otherwise noted, this copyright work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/. 3 BOOK INDUSTRY COLLABORATIVE COUNCIL Contents Membership of the Book Industry Collaborative Council 8 Terms of Reference 10 Foreword 11 Executive summary 13 Introduction: Adapting to change 17 Priority issues: Areas where reform is needed 19 Copyright 20 Data 21 Distribution 22 Exports 24 Lending rights 24 Scholarly book publishing 25 Future skills strategy 26 Strategies to improve capability 28 Copyright 29 Data: Models for industry data collection 29 Distribution 30 Exports 32 Lending rights 33 Scholarly book publishing 35 Future skills strategy 36 Implementation 38 Copyright 39 Data 40 Distribution 41 Exports 43 Lending rights 44 Scholarly book publishing 44 Future skills strategy 45 The book industry and Australian -

Inaugural Samsung Aacta Awards

INAUGURAL SAMSUNG AACTA AWARDS SAMSUNG AACTA AWARDS CEREMONY Tuesday 31 January 2012 - Sydney Opera House, Sydney AACTA AWARD FOR BEST YOUNG ACTOR Olivia DeJonge. Good Pretender. Emma Jefferson. My Place, Series 2 ‐ Episode 17 '1848 ‐ Johanna'. ABC3 Lara Robinson. Cloudstreet ‐ Part 1. FOXTEL ‐ Showcase Lucas Yeeda. Mad Bastards. TELEVISION AACTA AWARD FOR BEST TELEVISION DRAMA SERIES East West 101, Season 3 ‐ The Heroes' Journey. Steve Knapman, Kris Wyld. SBS Offspring, Season 2. John Edwards, Imogen Banks. Network Ten Rake. Ian Collie, Peter Duncan, Richard Roxburgh. ABC1 Spirited, Season 2. Claudia Karvan, Jacquelin Perske. FOXTEL ‐ W AACTA AWARD FOR BEST TELEFEATURE, MINI SERIES OR SHORT RUN SERIES Cloudstreet. Greg Haddrick, Brenda Pam. FOXTEL ‐ Showcase Paper Giants: The Birth Of Cleo. John Edwards, Karen Radzyner. ABC1 Sisters Of War. Andrew Wiseman. ABC1 The Slap. Tony Ayres, Helen Bowden, Michael McMahon. ABC1 AACTA AWARD FOR BEST LIGHT ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION SERIES The Gruen Transfer, Series 4. Andrew Denton, Anita Jacoby, Jon Casimir. ABC1 Hungry Beast, Series 3. Andrew Denton, Anita Jacoby, Andy Nehl, Jon Casimir. ABC1 Judith Lucy's Spiritual Journey. Todd Abbott. ABC1 Junior MasterChef, Series 1. Tara McWilliams. Network Ten RocKwiz. Brian Nankervis, Ken Connor, Peter Bain‐Hogg, Joe Connor. SBS AACTA AWARD FOR BEST DIRECTION IN TELEVISION Paper Giants: The Birth Of Cleo ‐ Episode 1. Daina Reid. ABC1 The Slap ‐ Episode 1 ‘Hector’. Jessica Hobbs. ABC1 The Slap ‐ Episode 3 ‘Harry’. Matthew Saville. ABC1 Small Time Gangster ‐ Episode 1 'Jingle Bells'. Jeffrey Walker. FOXTEL ‐ Movie Network AACTA AWARD FOR BEST SCREENPLAY IN TELEVISION Cloudstreet ‐ Part 3. Tim Winton, Ellen Fontana. FOXTEL ‐ Showcase Laid ‐ Episode 3. -

Law & Disorder

LAW & DISORDER RAKE LAW & DISORDER RAKE SERIES FOUR / 8 X ONE HOUR TV SERIES THURSDAY MAY 19 8.30PM STARRING RICHARD ROXBURGH WRITTEN BY PETER DUNCAN & ANDREW KNIGHT PRODUCED BY IAN COLLIE, PETER DUNCAN & RICHARD ROXBURGH ESSENTIAL MEDIA & BLOW BY BLOW MEDIA CONTACT Kristine Way / ABC TV Publicity T 02 8333 3844 M 0419 969 282 E [email protected] SERIES SYNOPSIS Last seen dangling from a balloon road leading straight to our dark drifting across the Sydney skyline, corridors of power. Cleaver Greene (Richard Roxburgh) Twisting and weaving the stories of crashes back to earth - literally and the ensemble of characters we’ve metaphorically, when he’s propelled grown to love over three stellar through a harbourside window into the seasons, Season 4 of Rake continues unwelcoming embrace of chaos past. the misadventures of dissolute Cleaver Fleeing certain revenge, Cleaver Greene and casts the fool’s gaze on all hightails it to a quiet country town, the levels of politics, the legal system, and reluctant member of a congregation our wider fears and obsessions. led by a stern, decent reverend and ALSO STARS Russell Dykstra, Danielle his flirtatious daughter. Before long Cormack, Matt Day, Adrienne Cleaver’s being chased back to Sin City. Pickering, Caroline Brazier, Kate Box, But Sydney has become a dark Keegan Joyce and Damien Garvey. place: terrorist threats and a loss of GUEST APPEARANCES from Miriam faith in authority have seen it take a Margolyes, Justine Clarke, Tasma turn towards the dystopian. When Walton, John Waters, Simon Burke, Cleaver finally emerges, he will be Rachael Blake, Rhys Muldoon, Louise accompanied by a Mistress of the Siversen and Sonia Todd. -

Clickview ATOM Guides 1 Videos with ATOM Study Guides Title Exchange Video Link 88

ClickView ATOM Guides Videos with ATOM Study Guides Title Exchange Video Link 88 http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/8341/88 http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/21821/the-100- 100+ Club club 1606 and 1770 - A Tale Of Two Discoveries https://clickviewcurator.com/exchange/programs/5240960 http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/8527/8mmm- 8MMM Aboriginal Radio aboriginal-radio-episode-1 http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/21963/900- 900 Neighbours neighbours http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/series/11149/a-case-for- A Case for the Coroner the-coroner?sort=atoz http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/12998/a-fighting- A Fighting Chance chance https://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/33771/a-good- A Good Man man http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/13993/a-law- A Law Unto Himself unto-himself http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/33808/a-sense-of- A Sense Of Place place http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/3226024/a-sense- A Sense Of Self of-self A Thousand Encores - The Ballets http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/32209/a- Russes In Australia thousand-encores-the-ballets-russes-in-australia https://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/25815/accentuat Accentuate The Positive e-the-positive Acid Ocean http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/13983/acid-ocean http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/series/8583/addicted-to- Addicted To Money money/videos/53988/who-killed-the-economy- http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/201031/afghanist -

Best of the Sydney Film Fest Screens in Newcastle

MEDIA RELEASE EMBARGOED UNTIL 11.00am WEDNESDAY 10 MAY 2017 BEST OF THE SYDNEY FILM FEST SCREENS IN NEWCASTLE Sydney Film Festival’s 2017 touring program, the Travelling Film Festival, returns to Tower Cinemas, Newcastle 23-25 June, with a selection of nine local and international award winning and festival favourite films. “Seven features and two documentaries will premiere in Newcastle, opening with Australia’s first Muslim comedy Ali’s Wedding by award winning television director Jeffrey Walker,” said Travelling Film Festival Manager Karina Libbey. “Closing the Festival is new documentary We Don’t Need a Map, from acclaimed Australian First Nation filmmaker Warwick Thornton. The film will be fresh from opening the Sydney Film Festival and competing in the Official Competition for the $60,000 Sydney Film Prize,” she said. “The Festival is thrilled to be returning to Newcastle right off the back of a huge Sydney Film Festival June 7- 18. Of course, we’ll be bringing all the hot picks from the Festival with us, Newcastle being the first centre in regional Australia to see these films,” she said. The Program: . Ali’s Wedding is history in the making - Australia’s first Muslim rom-com. This Australian comedy won an AWGIE for Best Original Screenplay, and is based on the real-life experience of lead actor Osamah Sami, whose arranged marriage lasted less than two hours. The smart screenplay by Sami and Andrew Knight (Hacksaw Ridge, Rake, Jack Irish) tells a humorous, authentic and poignant tale about family life in multicultural Australia. Stylishly directed by Jeffrey Walker (Modern Family, Angry Boys), the film boasts a terrific cast including Don Hany as Ali’s father. -

YEAR in REVIEW Celebrating Australian Screen Success and a Record Year for AFI | AACTA YEAR in REVIEW CONTENTS

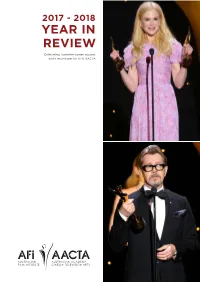

2017 - 2018 YEAR IN REVIEW Celebrating Australian screen success and a record year for AFI | AACTA YEAR IN REVIEW CONTENTS Welcomes 4 7th AACTA Awards presented by Foxtel 8 7th AACTA International Awards 12 Longford Lyell Award 16 Trailblazer Award 18 Byron Kennedy Award 20 Asia International Engagement Program 22 2017 Member Events Program Highlights 27 2018 Member Events Program 29 AACTA TV 32 #SocialShorts 34 Meet the Nominees presented by AFTRS 36 Social Media Highlights 38 In Memoriam 40 Winners and Nominees 42 7th AACTA Awards Jurors 46 Acknowledgements 47 Partners 48 Publisher Australian Film Institute | Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts Design and Layout Bradley Arden Print Partner Kwik Kopy Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication. The publisher does not accept liability for errors or omissions. Similarly, every effort has been made to obtain permission from the copyright holders for material that appears in this publication. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher. Comments and opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of AFI | AACTA, which accepts no responsibility for these comments and opinions. This collection © Copyright 2018 AFI | AACTA and individual contributors. Front Cover, top right: Nicole Kidman accepting the AACTA Awards for Best Supporting Actress (Lion) and Best Guest or Supporting Actress in a Television Drama (Top Of The Lake: China Girl). Bottom Celia Pacquola accepting the AACTA Award for Best right: Gary Oldman accepting the AACTA International Award for Performance in a Television Comedy (Rosehaven). Best Lead Actor (Darkest Hour). YEAR IN REVIEW WELCOMES 2017 was an incredibly strong year for the Australian Academy and for the Australian screen industry at large. -

The Pedagogy of Television

To educate and entertain: the pedagogy of television Ava Laure Parsemain A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of the Arts & Media Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences September 2015 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Parsemain First name: Laure Other name/s: Ava Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: The School of the Arts and Media Faculty: The Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Title: To educate and entertain: the pedagogy of television Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Many media scholars agree that television can be used as an informal site of teaching and learning. However, little is known about how television teaches. This thesis explores the pedagogy of television by investigating the processes by which television teaches and viewers learn. It addresses the following questions: how does television teach through production techniques and textual features? How do viewers learn from television? To investigate televisual pedagogy as a communicative process, this study links producers' discourses, audiovisual textuality and audience responses. By connecting production, text and reception, it shows how teaching and learning interact in the context of televisual communication. Taking into account the distinction between public service and commercial television and the traditional demarcation between programmes that are explicitly produced to educate and those that are produced primarily to entertain, it examines the production, textual features, and reception of two Australian programmes: Who Do You Think You Are?, a documentary seri es broadcast on the public service channel SBS, and Home and Away, a soap opera broadcast on the commercial Seven Network. -

19.12 Cv.Pages

ANDREW COMMIS ACS / DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY FEATURE FILMS : HIGH GROUND Director : Stephen Johnson / Producers : David Jowsey, Greer Simpkin & Maggie Miles / Bunya Productions & Savage Films Cast : Jacob Junior Nayingal, Simon Baker, Witiyana Marika, Callan Mulvey, Caren Pistorius, Aaron Pederson & Jack Thompson 2020 Berlin Film Festival - Official Selection BABYTEETH Director : Shannon Murphy / Producer : Alex White & Jan Chapman / Whitefalk Films & Jan Chapman Films Cast : Ben Mendelsohn, Essie Davis, Eliza Scanlan, Toby Wallace & Emily Barclay 2019 Venice Film Festival - Official Competition ANGEL OF MINE Director : Kim Farrant / Producer : Brian Etting, Josh Etting & Su Armstrong / Garlin Films & SixtyFourSixty Cast : Noomi Rapace, Yvonne Strahovski, Luke Evans, Richard Roxburgh, Finn Little & Annika Whitely 2019 Australian Cinematographers Society [ACS] Gold Award GIRL ASLEEP Director : Rosemary Myers / Producer : Jo Dyer / Soft Tread & Windmill Cast : Bethany Whitmore, Harrison Feldman, Matthew Whittet, Amber McMahon & Eamon Farren 2017 Australian Film Critics Association (AFCA) Award - Best Feature Film 2017 6x Film Critics Circle of Australia [FCCA] Award nominations incl. Best Feature Film & Best Cinematography 2016 7x Australian Academy of Cinema & Television Arts [AACTA] Award nominations incl. Best Feature Film & Best Cinematography 2016 Seattle Film Festival - Official Competition Grand Jury Prize & Youth Jury Prize 2016 Berlin Film Festival - Official Selection 2016 Melbourne Film Festival - The Age Critics Prize THE REHEARSAL -

Doctor Doctor S3 Med

SEASON 3 MEDIA KIT AMANDA POULOS CATHERINE LAVELLE NINE PUBLICIST UNIT PUBLICIST T: 02 9965 2489 T: 02 9405 2880 M: 0414 503 418 M: 0413 885 595 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Australia’s favourite bad boy doctor has returned for a third series of the hit drama series, Doctor Doctor. The clock has run out on Doctor Hugh Knight’s (Rodger Corser) probation, leaving him free to return to the big smoke. But when tragedy strikes the Knight family, he’s going to find it harder than ever to leave the family farm. An outstanding cast has returned for the new series, including Rodger Corser (Hugh), Nicole da Silva (Charlie), Steve Bisley (Jim), Ryan Johnson (Matt), Tina Bursill (Meryl), Hayley McElhinney (Penny), Matt Castley (Ajax), Chloe Bayliss (Hayley), Charles Wu (Ken), Belinda Bromilow (Betty), Brittany Clark (Mia) and Uli Latukefu (Darren). Joining the cast are Vince Colosimo, Miranda Tapsell, Andrea Demetriades, Don Hany, Matt Okine and many others. Doctor Doctor was filmed in Sydney and country NSW and was produced by Easy Tiger Productions for Nine with the assistance of Create NSW. © 2018 Easy Tiger Productions, Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd, Create NSW. 2 SYNOPSIS The clock has run out on Hugh’s (Rodger Corser) probation leaving him free to return to Sydney, but when tragedy strikes the Knight family, he’s going to find it harder to abandon Whyhope than ever. It’s three months on and the Knight family have been thrown a wild card – Jim (Steve Bisley) has had a heart attack and died.