Dl-RWKN T WATE R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jennings Ale 2Alt

jennings 4 day ambleside ale trail Day 3 - langdale hotel, elterwater - wordsworth hotel, grasmere This is the peak bagging day of the trip. After leaving the Langdale Hotel the route heads out along the old tracks down Langdale to the hotel at the foot of Stickle Gill. From here a fairly stiff climb gives access to the dramatic crag ringed corrie occupied by Stickle Tarn. Unlikely as it might seem standing amongst all the towering crags there is a sneaky route to the surrounding summits from the tarn. It leads in zig-zags to the dip between Harrison Stickle and Pavey Ark from where both peaks can easily be gained. The obvious diagonal line that cuts across the crags of Pavey Ark is Jack’s Rake which is a popular scramble. The rest of the crag provides top quality rock climbs. Having summited these two a big loop takes in Thunacar Knott and Sergeant Man, and then heads down, via Blea Rigg and Easedale Tarn, to the pastoral beauty of Grasmere and the welcome sight of the Wordsworth Hotel where a lovely, refreshing pint of Cumberland Ale awaits you! Before setting off please make sure you plot the suggested route on OS maps and pack a compass. They are essential for a safe, enjoyable day in the hills! Grade: Time/effort 3, Navigation 3, Technicality 3 stunning unrestricted views to the south out over Langdale and Start: Langdale Hotel, Elterwater GR NY326051 towards the giants of the Coniston Fells. The next of the ‘Pikes’ Finish: Wordsworth Hotel, Grasmere GR NY337074 is Thunacar Knott. -

Mountain Accidents 2009

LAKE DISTRICT SEARCH & MOUNTAIN RESCUE ASSOCIATION MOUNTAIN ACCIDENTS 2009 Belles Knotts from ‘Wainwright’s Central Fells’ and reproduced By courtesy of the Westmorland Gazette The Lake District Search and Mountain Rescue Association would like to acknowledge the contributions given to this association by all members of the public, public bodies and trusts. In particular, this association gratefully acknowledges the assistance given by Cumbria Constabulary. and Cumbria Police Authority This Report is issued by The Lake District Search and Mountain Rescue Association in the interests of all mountain users. Lake District Search and Mountain Rescue Association President: Mike Nixon MBE Chairman: Richard Warren 8 Foxhouses Road, Whitehaven, Cumbria, CA28 8AF Tel: 01946 62176 Email: [email protected] Secretary: Simeon Leech Rowan Cottage, The Gill, Ulverston, Cumbria, LA12 7BN Tel: 01229 480768 Email: [email protected] Treasurer: Richard Longman The Croft, Nethertown Road, St Bees, Cumbria, CA27 0AY Tel: 01946 823785 Email: [email protected] Ass. Sec.: Incident Officer: Ged Feeney 57 Castlesteads Drive, Carlisle, Cumbria CA2 7XD Tel: 01228 525709 Email [email protected] This is an umbrella organisation covering the Lake District teams, police representatives and other organisations interested in mountain rescue, such as RAF and National Park Rangers. The purpose of the Lake District Search and Mountain Rescue Association is to act as a link between the national Mountain Rescue Council and all other interested bodies. The association speaks out and acts on behalf of the teams on matters relating to Lake District mountain rescue as a whole. It also fosters publicity aimed at the prevention of mountain accidents. -

Jennings Ale Alt

jennings 4 day helvellyn ale trail Grade: Time/effort 5, Navigation 3, Technicality 3 Start: Inn on the Lake, Glenridding GR NY386170 Finish: Inn on the Lake, Glenridding GR NY386170 Distance: 31.2 miles (50.2km) Time: 4 days Height gain: 3016m Maps: OS Landranger 90 (1:50 000), OS Explorer OL 4 ,5,6 & 7 (1:25 000), Harveys' Superwalker (1:25 000) Lakeland Central and Lakeland North, British Mountain Maps Lake District (1:40 000) Over four days this mini expedition will take you from the sublime pastoral delights of some of the Lake District’s most beautiful villages and hamlets and to the top of its best loved summits. On the way round you will be rewarded with stunning views of lakes, tarns, crags and ridges that can only be witnessed by those prepared to put the effort in and tread the fell top paths. The journey begins with a stay at the Inn on the Lake, on the pristine shores of Ullswater and heads for Grasmere and the Travellers Rest via an ancient packhorse route. Then it’s onto the Scafell Hotel in Borrowdale via one of the best viewpoint summits in the Lake District. After that comes an intimate tour of Watendlath and the Armboth Fells. Finally, as a fitting finish, the route tops out with a visit to the lofty summit of Helvellyn and heads back to the Inn on the Lake for a well earned pint of Jennings Cocker Hoop or Cumberland Ale. Greenside building, Helvellyn. jennings 4 day helvellyn ale trail Day 1 - inn on the lake, glenridding - the travellers’rest, grasmere After a night at the Inn on the Lake on the shores of Ullswater the day starts with a brief climb past the beautifully situated Lanty’s Tarn, which was created by the Marshall Family of Patterdale Hall in pre-refrigerator days to supply ice for an underground ‘Cold House’ ready for use in the summer months! It then settles into its rhythm by following the ancient packhorse route around the southern edge of the Helvellyn Range via the high pass at Grisedale Hause. -

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

4-Night Southern Lake District Guided Walking Holiday

4-Night Southern Lake District Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: CNBOB-4 2, 3 & 5 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Relax and admire magnificent mountain views from our Country House on the shores of Conistonwater. Walk in the footsteps of Wordsworth, Ruskin and Beatrix Potter, as you discover the places that stirred their imaginations. Enjoy the stunning mountain scenes with lakeside strolls, taking a cruise across the lake on the steam yacht Gondola, or enjoy getting nose-to-nose with the high peaks as you explore their heights. Whatever your passion, you’ll be struck with awe as you explore this much-loved area of the Lake District. HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of the South Lakes on foot • Choose a valley bottom stroll or reach for the summits on fell walks and horseshoe hikes • Let our experienced leaders bring classic routes and hidden gems to life • Visit charming Lakeland villages • A relaxed pace of discovery in a sociable group keen to get some fresh air in one of England’s most beautiful walking areas www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • Evenings in our country house where you can share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 2, 3 and 5. Our best-selling Guided Walking holidays run throughout the year - with their daily choice of up to 3 walks, these breaks are ideal for anyone who enjoys exploring the countryside on foot. -

Wainwright's Central Fells

Achille Ratti Long Walk - 22nd April 2017 – Wainwright’s Central Fells in a day by Natasha Fellowes and Chris Lloyd I know a lot of fell runners who are happy to get up at silly o'clock to go for a day out. I love a day out but I don't love the early get ups, so when Dave Makin told me it would be a 4am start this time for the annual Achille Ratti Long Walk, the idea took a bit of getting used to. The route he had planned was the Wainwright's Central Fells. There are 27 of them and he had estimated the distance at 40 ish miles, which also took some getting used to. A medium Long Walk and a short Long Walk had also been planned but I was keen to get the miles into my legs. So after an early night, a short sleep and a quick breakfast we set off prompt at 4am in cool dry conditions from Bishop’s Scale, our club hut in Langdale. Our first top, Loughrigg, involved a bit of a walk along the road but it passed quickly enough and we were on the top in just under an hour. The familiar tops of Silver Howe and Blea Rigg then came and went as the sun rose on the ridge that is our club's back garden. I wondered whether anyone else at the hut had got up yet. The morning then started to be more fun as we turned right and into new territory for me. -

SPRINGFIELD FELLWALKING CLUB 6Th JULY 2019 – 7Th DEC 2019

SPRINGFIELD FELLWALKING CLUB 6th JULY 2019 – 7th DEC 2019 WALK NO WALK DATE VENUE 1242 06/07/19 GLENRIDDING 1243 20/07/19 MALHAM 1244 03/08/19 BASSENTHWAITE 1245 17/08/19 HEBDEN BRIDGE - HAWORTH 1246 31/08/19 N.D.G. HOTEL - GRASMERE 1247 14/09/19 LOGGERHEADS ( no pub stop ) 1248 28/09/19 BROUGHTON - IN - FURNESS 1249 12/10/19 GRASMERE 1250 26/10/19 HOLLINGWORTH LAKE 1251 09/11/19 TROUTBECK 1252 23/11/19 HAWKSHEAD 1253 07/12/19 CLAPHAM www.springfieldfellwalking.co.uk PICK UP POINTS A CHANGE OF CLOTHING MUST BE LEFT ON THE COACH. ONE MEAL AND DRINKS TO BE CARRIED. EMERGENCIES ; DIAL 999 ASK FOR MOUNTAIN RESCUE PICK UP POINT TIME BISPHAM RD. ROUNDABOUT 7-30 PLYMOUTH RD. ROUNDABOUT 7-36 NEWTON DRIVE ROUNDABOUT 7-40 PRESTON NEW RD. 7-49 ( Macdonalds ) PADDOCK DRIVE 7-50 KIRKHAM SQUARE 7-57 CARR HILL RD. 7-59 BELL & BOTTLE 8-02 CLIFTON VILLAGE ( 1st bus stop on entering village ) 8-05 LEA POST OFFICE/LEA CLUB 8-13 CLIFTON AVE. 8-15 LANE ENDS ( Bus shelter ) 8-19 BLACK BULL FULWOOD 8-23 ROUTE Start – Bispham Roundabout – A587 – Preston New Road – Kirkham – Clifton Village – Lea – Ashton – Black Bull Fulwood WALK NO WALK DATE VENUE 1242 06/07/19 GLENRIDDING MAP ; EXPLORER OL 5 ENGLISH LAKES N E AREA ‘A’ – COW BRIDGE – GALE CRAG – HARTSOP ABOVE HOW – HART CRAG – FAIRFIELD – COFFA PIKE – DEEPDALE HAUSE – ST SUNDAY CRAG – THORN HOW - LANTY’S TARN – GLENRIDDING LEADER 9.1/2 MLS ; 3600’ TL. ASC. ‘B’ – PATTERDALE – BOREDALE HAUSE – PLACE FELL – MORTAR CRAG – LOW MOSS – SCALEHOW WOOD – SILVER BAY – SIDE FARM – GRISEDALE BRIDGE – GLENRIDDING LEADER 8.1/2 MLS ; 2400’ TL. -

7-Night Southern Lake District Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Southern Lake District Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: CNBOB-7 2, 3 & 5 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Relax and admire magnificent mountain views from our Country House on the shores of Conistonwater. Walk in the footsteps of Wordsworth, Ruskin and Beatrix Potter, as you discover the places that stirred their imaginations. Enjoy the stunning mountain scenes with lakeside strolls, taking a cruise across the lake on the steam yacht Gondola, or enjoy getting nose-to-nose with the high peaks as you explore their heights. Whatever your passion, you’ll be struck with awe as you explore this much-loved area of the Lake District. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking and 1 free day • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of the South Lakes on foot • Choose a valley bottom stroll or reach for the summits on fell walks and horseshoe hikes • Let our experienced leaders bring classic routes and hidden gems to life • Visit charming Lakeland villages • A relaxed pace of discovery in a sociable group keen to get some fresh air in one of England’s most beautiful walking areas • Evenings in our country house where you can share a drink and re-live the day’s adventures TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 2, 3 and 5. -

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - the Check List Thirty-Six Circular Walks Covering All the Peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - The Check List Thirty-six circular walks covering all the peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells. This list is provided for those of you wishing to complete the Wainwright's in 36 walks. Simply tick off each mountain as completed when the task of climbing it has been accomplished. Mountain Book Walk Completed Arnison Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birkhouse Moor The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birks The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Catstye Cam The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Clough Head The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Dollywaggon Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Dove Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Fairfield The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Glenridding Dodd The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Gowbarrow Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Dodd The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Great Mell Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Rigg The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Side The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Hartsop Above How The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit Helvellyn The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Heron Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Mountain Book Walk Completed High Hartsop Dodd The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit High Pike (Scandale) The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Little Hart Crag -

JOURNAL 1979 • CONTENTS C4 CO Diary for 1979 3

THE ASSOCIATION • OF BRITISH MEMBERS OF THE SWISS ALPINE CLUB IS JOURNAL 1979 • CONTENTS c4 CO Diary for 1979 3 Editorial 5 The Scottish Garwhal Expedition 1977 by Frank Schweitzer 11 • • Prelude Français by Frank Solari 17 A short walk in the Black Cuillin! by Gordon Gadsby 21 Descent from the Matterhorn by Hamish M. Brown 26 Association Activities The Annual General Meeting 27 Association Accounts 29 The Annual Dinner 32 The Outdoor Meets 33 The Library 1 • 39 t- Members' Climbs and Excursions 40 Obituaries, Robin Fedden, John and Freda Kemsley 62 List of Past and Present Officers 63 Complete List of Members 66 DIARY FOR 1979 The outdoor events for the second half of 1979 were not settled at the time of going to press. The editor apologises for the omission, which will be made good In the Circulars. The list of indoor events is complete except for the venue for the Annual Dinner and details of the A.G.M. January 9th Lecture, Tony Husbands, 'Mountain Reminiscences'. February 7th Fondue evening. February 10th Northern Dinner Meet at Patterdale. Douglas Milner to llth will speak on 'Mountains for Pleasure'. March 3rd to 4th Joint Meet with A.C., Brackenclose, Wasdale Head. VIKING& Book directly through Peter Fleming. March 7th Lecture, Don Hodge, 'Bernese Oberland'. March 9th to 10th Maintenance meet Patterdale. Book through John OBIRE01IAN61-urteiT Cohen. April 4th Lecture, Alan Hankinson, 'Early Climbing in the Lake 01141177 GEAR AT AY7RACTIVE PRICE& District'. STOCKED BY LEADING WSW SPECIALISTS April 13th to 16th Informal Easter Meet at Patterdale. Hut reserved for members. -

The Forty-Seventh 6

The Forty-Seventh 6 - 16 August 2018 At Rydal Hall The Trustees of the Wordsworth Conference Foundation gratefully acknowledge a generous endowment towards bursaries from the late Ena Wordsworth. Other bursaries are funded by anonymous donors or by the Charity itself. The Trustees also wish to thank the staff at both The Wordsworth Trust and Rydal Hall for their hospitality to conference participants throughout the event. Regular Events Early Morning walks: 07.15 (07.00 on sedentary days) Breakfast: 08.15 (earlier on changeover day) Coffee: 10.30 – 11.00 Tea: 16.15 – 17.00 (when applicable) Dinner: 19.00 (later on changeover day) The Wordsworth Conference Foundation Summer Conference Director Nicholas Roe Foundation Chairman Richard Gravil ‘A’ Walks Leader Elsa Hammond Postgraduate Representative Sharon Tai Conference Administrator Carrie Taylor Treasurer Oliver Clarkson Trustees Simon Bainbridge, David Chandler, Oliver Clarkson, Stephen Gill, Richard Gravil, Elsa Hammond, Felicity James, Stacey McDowell, Michael O’Neill, Thomas Owens, Daniel Robinson, Nicholas Roe The Wordsworth Conference Foundation is a Company Limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Company No. 6556368 Registered Charity No. 1124319 1 Conference Programme Notices Keynote Lectures Special Events Leisure Events Tea/Meals Foundation Events (Names in bold red are bursary holders) Leisure events, timings and destinations are subjected to change Part One: 6-11 August ****Please see the notes on Lecture and Paper Presentations on page 10**** Monday 6 August Travel: Euston to Oxenholme 11.30-14.08 [direct] All trains Manchester Airport to Oxenholme 12.10 – 13.32 [direct] require a Glasgow Central to Oxenholme 12.40 – 14.22 [direct] change at Glasgow Airport to Oxenholme 11.35 – 14.22 [2 changes] Oxenholme Oxenholme to Windermere 14.00-14.21; 14.51-1509; 15.37-15.58 [all direct] for Windermere Bus 555 to Rydal Church leaves Windermere station at 9 and 39 minutes connection. -

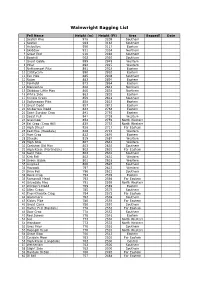

Wainwright Bagging List

Wainwright Bagging List Fell Name Height (m) Height (Ft) Area Bagged? Date 1 Scafell Pike 978 3209 Southern 2 Scafell 964 3163 Southern 3 Helvellyn 950 3117 Eastern 4 Skiddaw 931 3054 Northern 5 Great End 910 2986 Southern 6 Bowfell 902 2959 Southern 7 Great Gable 899 2949 Western 8 Pillar 892 2927 Western 9 Nethermost Pike 891 2923 Eastern 10 Catstycam 890 2920 Eastern 11 Esk Pike 885 2904 Southern 12 Raise 883 2897 Eastern 13 Fairfield 873 2864 Eastern 14 Blencathra 868 2848 Northern 15 Skiddaw Little Man 865 2838 Northern 16 White Side 863 2832 Eastern 17 Crinkle Crags 859 2818 Southern 18 Dollywagon Pike 858 2815 Eastern 19 Great Dodd 857 2812 Eastern 20 Stybarrow Dodd 843 2766 Eastern 21 Saint Sunday Crag 841 2759 Eastern 22 Scoat Fell 841 2759 Western 23 Grasmoor 852 2759 North Western 24 Eel Crag (Crag Hill) 839 2753 North Western 25 High Street 828 2717 Far Eastern 26 Red Pike (Wasdale) 826 2710 Western 27 Hart Crag 822 2697 Eastern 28 Steeple 819 2687 Western 29 High Stile 807 2648 Western 30 Coniston Old Man 803 2635 Southern 31 High Raise (Martindale) 802 2631 Far Eastern 32 Swirl How 802 2631 Southern 33 Kirk Fell 802 2631 Western 34 Green Gable 801 2628 Western 35 Lingmell 800 2625 Southern 36 Haycock 797 2615 Western 37 Brim Fell 796 2612 Southern 38 Dove Crag 792 2598 Eastern 39 Rampsgill Head 792 2598 Far Eastern 40 Grisedale Pike 791 2595 North Western 41 Watson's Dodd 789 2589 Eastern 42 Allen Crags 785 2575 Southern 43 Thornthwaite Crag 784 2572 Far Eastern 44 Glaramara 783 2569 Southern 45 Kidsty Pike 780 2559 Far