Philippine Law Journal Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 Hours)

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 hours) Eat your way around Binondo, the Philippines’ Chinatown. Located across the Pasig River from the walled city of Intramuros, Binondo was formally established in 1594, and is believed to be the oldest Chinatown in the world. It is the center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino-Chinese merchants, and given the historic reach of Chinese trading in the Pacific, it has been a hub of Chinese commerce in the Philippines since before the first Spanish colonizers arrived in the Philippines in 1521. Before World War II, Binondo was the center of the banking and financial community in the Philippines, housing insurance companies, commercial banks and other financial institutions from Britain and the United States. These banks were located mostly along Escólta, which used to be called the "Wall Street of the Philippines". Binondo remains a center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino- Chinese merchants and is famous for its diverse offerings of Chinese cuisine. Enjoy walking around the streets of Binondo, taking in Tsinoy (Chinese-Filipino) history through various Chinese specialties from its small and cozy restaurants. Have a taste of fried Chinese Lumpia, Kuchay Empanada and Misua Guisado at Quick Snack located along Carvajal Street; Kiampong Rice and Peanut Balls at Café Mezzanine; Kuchay Dumplings at Dong Bei Dumplings and the growing famous Beef Kan Pan of Lan Zhou La Mien. References: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binondo,_Manila TIME ITINERARY 0800H Pick-up -

Landbank of the Philippines Post-Contract Award Disclosure As of March 15, 2021

Landbank of the Philippines Post-Contract Award Disclosure As of March 15, 2021 APPROVED AMOUNT OF NAME OF WINNING OFFICIAL BUSINESS ADDRESS CONTRACT DATE OF DATE OF IMPLEMENTING OFFICE/UNIT OF PROJECT NAME BUDGET FOR THE CONTRACT BIDDER OF THE WINNING BIDDER PERIOD AWARD ACCEPTANCE THE BANK CONTRACT AWARDED TWO (2) YEARS SUBSCRIPTION TO 816,000.00 816,000.00 CONVERGE INFORMATION Reliance Center Annex 1, 99 E. Rodriguez Jr. 10CD/NTP 05-Jan-21 05-Jan-21 NETWORK OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT (NOD) TWO (2) UNITS CONVERGE IBIZ AND COMMUNICATIONS Ave., Ugong, Pasig City (BROADBAND) INTERNET FOR TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS, T - 8667-0888 LANDBANK DIOSDADO MACAPAGAL INC. F - 8667-0895 HALL AND ADJACENT ROOMS E - [email protected] MS. PAMELA C. DEL ROSARIO AIRCONDITIONINIG UNITS 555,600.00 522,410.59 MARCO, INC. 12 Matatag Street, Diliman, Quezon City 30CD/NTP AND 05-Jan-21 05-Jan-21 C/O PROJECT MANAGEMENT & ENGINEERING T - 8929-3767 ADVICE FROM DEPARTMENT (PMED) F - 8920-4598 PMED - HIMAMAYLAN BR. E - [email protected] MR. OLIVERT Y. DUYA ONE (1) YEAR HARDWARE 47,000,000.00 47,000,000.00 IBM PHILIPPINES, INC. 28/F One World Place, 32nd Street, ONE (1) YEAR 05-Jan-21 05-Jan-21 DATA CENTER MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT MAINTENANCE SERVICES FOR IBM Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City BEGINNING ON (DCMD) MACHINES T - 8995-2426 THE RECEIPT OF CP - 0917-6344723 NTP E - [email protected] MR. RAMIL D. CABODIL VARIOUS VAULTS AND SAFES 627,710.00 341,500.00 MOSLER PHILIPPINES, INC. 8011 Elisco Road, Ibayo, Tipas, Taguiig City 30CD/NTP AND 06-Jan-21 06-Jan-21 C/O PROJECT MANAGEMENT & ENGINEERING T - 8641-4054 ADVICE FROM DEPARTMENT (PMED) E - [email protected] PMED - BALINGASAG BRANCH MR. -

20 October 2010 Philippine Stock Exchange Disclosures Department 3/F, Tower One and Exchange Plaza Ayala Triangle, Ayala Avenue

20 October 2010 Philippine Stock Exchange Disclosures Department 3/F, Tower One and Exchange Plaza Ayala Triangle, Ayala Avenue Makati City Attention : Ms. Janet Encarnacion Head – Disclosures Department Re : ROXAS AND COMPANY, INC. (Formerly CADP GROUP CORPORATION) ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ Gentlemen: We respectfully submit the Annual List of Stockholders of Roxas and Company, Inc. (formerly CADP Group Corporation and herein referred to as the “Company”) as of Record Date, 15 October 2010, prepared by Unionbank Stock Transfer Unit, the Company’s stock transfer agent. Very truly yours, FRITZIE P. TANGKIA‐FABRICANTE Asst. Corporate Secretary/Compliance Officer 7th Floor Cacho Gonzales Building 101 Aguirre Street, Legaspi Village 1229 Makati City Tel No.: (02) 810‐8901 www.roxascompany.com.ph ROXAS AND COMPANY, INC. List of Stockholders as of Record Date 15 October 2010 SN STOCKHOLDERS NAME ADDRESS SHARES 10082856 A. SORIANO CORPORATION SORIANO BUILDING, MAKATI CITY 2,710 10082014 ABAD AURORA C/O BANK OF ASIA, DASMARINAS MANILA 40 10071504 ABAQUIN GIL 3666-C GEN. A. LUNA ST. BANOKAL, MAKATI, MM 402 10071514 ABAQUIN LOURDES M. #6 RIZAL ST., AYALA HEIGHTS QUEZON CITY 742 10079516 ABAT NESTOR A. PASIG BOULEVARD,BARRIO PINEDA PASIG CITY 538 10082024 ABAYA AMELIA R. 153 LT., ARTIAGA, SAN JUAN, MM 3,340 10082034 ABAYA MELCHOR R. 153 LT., ARTIAGA, SAN JUAN, MM 1,560 10082044 ABAYA VICENTE R. 153 LT., ARTIAGA, SAN JUAN, MM 3,340 C/O CADP CG BUILDING, 101 AGUIRRE STREET 10079637 ABELEDA ANASTACIO 18 LEGASPI VILLAGE, MAKATI CITY C/O CADP CG BUILDING, 101 AGUIRRE STREET 10079647 ABELLERA ERNESTO 179 LEGASPI VILLAGE, MAKATI CITY C/O CADP CG BUILDING, 101 AGUIRRE STREET 10079657 ABELLERA SUSAN C. -

No. Company Star

Fair Trade Enforcement Bureau-DTI Business Licensing and Accreditation Division LIST OF ACCREDITED SERVICE AND REPAIR SHOPS As of November 30, 2019 No. Star- Expiry Company Classific Address City Contact Person Tel. No. E-mail Category Date ation 1 (FMEI) Fernando Medical Enterprises 1460-1462 E. Rodriguez Sr. Avenue, Quezon City Maria Victoria F. Gutierrez - Managing (02)727 1521; marivicgutierrez@f Medical/Dental 31-Dec-19 Inc. Immculate Concepcion, Quezon City Director (02)727 1532 ernandomedical.co m 2 08 Auto Services 1 Star 4 B. Serrano cor. William Shaw Street, Caloocan City Edson B. Cachuela - Proprietor (02)330 6907 Automotive (Excluding 31-Dec-19 Caloocan City Aircon Servicing) 3 1 Stop Battery Shop, Inc. 1 Star 214 Gen. Luis St., Novaliches, Quezon Quezon City Herminio DC. Castillo - President and (02)9360 2262 419 onestopbattery201 Automotive (Excluding 31-Dec-19 City General Manager 2859 [email protected] Aircon Servicing) 4 1-29 Car Aircon Service Center 1 Star B1 L1 Sheryll Mirra Street, Multinational Parañaque City Ma. Luz M. Reyes - Proprietress (02)821 1202 macuzreyes129@ Automotive (Including 31-Dec-19 Village, Parañaque City gmail.com Aircon Servicing) 5 1st Corinthean's Appliance Services 1 Star 515-B Quintas Street, CAA BF Int'l. Las Piñas City Felvicenso L. Arguelles - Owner (02)463 0229 vinzarguelles@yah Ref and Airconditioning 31-Dec-19 Village, Las Piñas City oo.com (Type A) 6 2539 Cycle Parts Enterprises 1 Star 2539 M-Roxas Street, Sta. Ana, Manila Manila Robert C. Quides - Owner (02)954 4704 iluvurobert@gmail. Automotive 31-Dec-19 com (Motorcycle/Small Engine Servicing) 7 3BMA Refrigeration & Airconditioning 1 Star 2 Don Pepe St., Sto. -

PHILIPPINE STATISTICAL ASSOCIATION Incorporated P. O. Box 3223, Manila

• PHILIPPINE STATISTICAL ASSOCIATION Incorporated P. O. Box 3223, Manila DIRECTORY OF INDIVIDUAL MEMBERS Recording Year of Admission September 30, 1957 -A- 1955 ACAYAN, Mrs. Dolores S.; NFSP-SPCMAI Joint Re search Dept., 404 Gonzaga Building, Rizal Avenue, Manila; 1989-C Pennsylvania, Manila. 1952 AGUIRRE, Tomas B.; Vice-President, Philippine Na tional Bank, Escolta, Manila. 1954 ALINO, Reinaldo; Assistant Director, Exchange Control Department, Central Bank of the Philippines, Manila, Tel. No. 3-23-31; 522 Bagumbayan St., Manila. 1954 ALONZO, Domingo Co; Chief Statistician, OSCS, Na tional Economic Council; Professorial Lecturer of Sta tistics, The Statistical Center, University of the Philip pines, Rizal Hall, Padre Faura, P. O. Box 479, Manila, Tel. 5-46-62; 1341-D Leroy, Paco, Manila. 1953 ALZATE, Loreto V.; Superintendent, Menzi & Co., Inc., Mati Project, 453 Claveria, Davao City; Menzi Mati Project, Mati, Davao. 1952 ANTIPORDA, Alfredo V.; Assistant Director, Foreign • Exchange Department, Central Bank of the Philip pines, Tel. 3-23-31; 567 Paltoc, Sta. Mesa, Manila. 1954 AROMIN, Policarpio Po; Administrative Officer, National Employment Service, 1003 Arlegui, Quiapo, Manila, Gov't. 2630 - Dial 3-90-96; 1240 Rosarito, Sampaloc, Manila. 1951 ':'AYCARDO, n-. Manuel Ma.; 178 Porvenir St., Pasay City, Tel. 8-24-84. -B- 1953 BACANI, Alberto Co; Head, Records Division, Regis hoar's Office. University of the East, Azcarraga, Tel. 3-36-81, Manila; No. 18 Illinois Street, Cubao, Quezon City, Tel. 7-44-48". * Founding Member • 187 • 1953 BALICKi\" .MissSophya M.; Statistical. Adviser, United States of America Operations Mission to the Philip pines (ICA), Dewey Boulevard, Manila, Tel. No. 5-57-51; 207 T.Alonzo, Parafiaque, Rizal, Tel. -

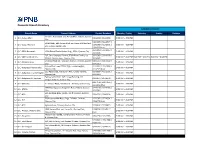

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE Branch Name Present Address Contact Numbers Monday - Friday Saturday Sunday Holidays cor Gen. Araneta St. and Aurora Blvd., Cubao, Quezon 1 Q.C.-Cubao Main 911-2916 / 912-1938 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 912-3070 / 912-2577 / SRMC Bldg., 901 Aurora Blvd. cor Harvard & Stanford 2 Q.C.-Cubao-Harvard 913-1068 / 912-2571 / 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Sts., Cubao, Quezon City 913-4503 (fax) 332-3014 / 332-3067 / 3 Q.C.-EDSA Roosevelt 1024 Global Trade Center Bldg., EDSA, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 332-4446 G/F, One Cyberpod Centris, EDSA Eton Centris, cor. 332-5368 / 332-6258 / 4 Q.C.-EDSA-Eton Centris 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM EDSA & Quezon Ave., Quezon City 332-6665 Elliptical Road cor. Kalayaan Avenue, Diliman, Quezon 920-3353 / 924-2660 / 5 Q.C.-Elliptical Road 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 924-2663 Aurora Blvd., near PSBA, Brgy. Loyola Heights, 421-2331 / 421-2330 / 6 Q.C.-Katipunan-Aurora Blvd. 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 421-2329 (fax) 335 Agcor Bldg., Katipunan Ave., Loyola Heights, 929-8814 / 433-2021 / 7 Q.C.-Katipunan-Loyola Heights 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 433-2022 February 07, 2014 : G/F, Linear Building, 142 8 Q.C.-Katipunan-St. Ignatius 912-8077 / 912-8078 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Katipunan Road, Quezon City 920-7158 / 920-7165 / 9 Q.C.-Matalino 21 Tempus Bldg., Matalino St., Diliman, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 924-8919 (fax) MWSS Compound, Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon 927-5443 / 922-3765 / 10 Q.C.-MWSS 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 922-3764 SRA Building, Brgy. -

Branch Name Address 168 Mall 168 Mall Shopping Center, Stall No

Branch Name Address 168 Mall 168 Mall Shopping Center, Stall No. 4H-01, Soler St., Binondo Manila A. MABINI 1353 A. Mabini St. Ermita Manila ACROPOLIS 191 Triquetra Bldg., E. Rodriguez Jr. ave., Libis. Q.C. ALABANG RCBC Building, Tierra Nueva Subd.,Alabang-Zapote Road, Alabang, Muntinlupa City ALABANG WEST SERVICE ROAD Alabang West Service Rd., cor Montillano St., and South Superhighway, Alabang, Muntinlupa City ANGELES - STO. CRISTO 243 Sto. Entierro St., Brgy. Sto. Cristo, Angeles City ANGELES CITY RCBC Bldg. Sto Rosario Street cor Teresa Ave, Angeles City ANTIQUE Solana cor. T.A. Fornier Sts., San Jose, Antique APARRI 108 J.P. Rizal St., Brgy. Centro 14, Aparri, Cagayan ARANETA CENTER G/F, Unit 111 Sampaguita Theatre Bldg., cor. Gen. Araneta and Gen. Rozas Sts., Cubao, Quezon City ARNAIZ 843 G/F Prudential Life Bldg., Arnaiz Ave., Legaspi Village, Makati City ARRANQUE 1001 Orient Star Bldg., Soler cor Masangkay Sts., Binondo, Manila ATENEO DE DAVAO EXTENSION OFFICE F-106 G/F Finster Building, Ateneo de Davao University Main Campus Cor., CM Recto Ave. & Roxas Ave., Davao City AYALA Unit 709, Tower One, Ayala Triangle, Ayala Ave. Makati City BACAO EXTENSION OFFICE Yokota Commercial Bldg. Bacao Road, Brgy Bacao 2, Gen. Trias, Cavite BACLARAN 21 Taft Ave. Baclaran Parañaque City BACOLOD LACSON Lourdes C. Centre II, 14th Lacson St., Bacolod City BACOLOD LIBERTAD Libertad Extension, Bacolod City BACOLOD MAIN cor. Rizal and Locsin Sts., Bacolod City BACOLOD SHOPPING Hilado St., Shopping, Bacolod City BACOOR Maraudi Bldg., Gen. E. Aguinaldo Highway, Brgy. Niog, Bacoor Cavite BAGUIO CITY RCBC Bldg., 20 Session Rd. -

PHILIPPINE STATISTICAL ASSOCIATION Incorporated P. 6. Box 3223, Manila DIRECTORY. of INDIVIDUAL MEMBERS MARCH 31, 1954 Aguirre

PHILIPPINE STATISTICAL ASSOCIATION Incorporated P. 6. Box 3223, Manila DIRECTORY. OF INDIVIDUAL MEMBERS MARCH 31, 1954 -A:- Aycardo, Dr. Manuel Ma. Chief, Division of Preventable Aguirre, Tomas B. Diseases Department of Economic Research Bureau of Health, Manila Central Bank of the Philippines :~,.. Man i I a -B- • Alip, Dr. Eufronio M. Bacani, Alberto C. 1312 Dos Castillas College of Commerce Sampaloc, Manila University of the East Man i I a Alino, Reinaldo Assistant Director Baldemor, Fabian Exchange Control Department National Rice & Corn Corporation Central Bank of the Philippines Manila Ma'nila Alonzo, Domingo Balicka, Miss Sophya Mathematics Department Statistical Adviser University of the Philippines U. S. Foreign Operations Diliman, Q.uezon City Administration Manila Alonzo, Dr. Agustin S. Dean, School of Arts & Sciences Bancod, Ricardo T. Manuel L. Quezon Educutional Philippine American Life Institution Insurance Co. Manila Wilson Building, Juan Luna 1\1 ani I a Alzate, Loreto V. Philippine Ra-Me Decorticating, Bantegui, Bernardino G. Inc. College of Liberal Arts J. M. Menzi Building University of the East 183 Soler Street 1\1 ani I a P. O. Box 394, Manila Bate, Celso S. Antiporda, Alfredo V. Exchange Control Department Exchange Control Department Central Bank ofthe Philippines Central Bank of the Philippines Man i I a Man i I a Benitez, Dean Cenrado Artiaga, Dr. Santiago c/o Philippine Women's University '1020 Taft Avenue, Manila Taft Avenue, Manila • 71 Blardony, M. -D- The Insular Life Assurance ce., Ltd. Dalisay, Dr. Amando Insular Life Bldg" Plaza Moraga Executive Officer Man i I a Philippine Council for United States Aid Braum, Dr. -

The City As Illusion and Promise

Ateneo de Manila University Archīum Ateneo Philosophy Department Faculty Publications Philosophy Department 10-2019 The City as Illusion and Promise Remmon E. Barbaza Follow this and additional works at: https://archium.ateneo.edu/philo-faculty-pubs Part of the Other Philosophy Commons Making Sense of the City Making Sense of the City REMMON E. BARBAZA Editor Ateneo de Manila University Press Ateneo de Manila University Press Bellarmine Hall, ADMU Campus Contents Loyola Heights, Katipunan Avenue Quezon City, Philippines Tel.: (632) 426-59-84 / Fax (632) 426-59-09 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ateneopress.org © 2019 by Ateneo de Manila University and Remmon E. Barbaza Copyright for each essay remains with the individual authors. Preface vii Cover design by Jan-Daniel S. Belmonte Remmon E. Barbaza Cover photograph by Remmon E. Barbaza Book design by Paolo Tiausas Great Transformations 1 The Political Economy of City-Building Megaprojects All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in the Manila Peri-urban Periphery stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or Jerik Cruz otherwise, without the written permission of the Publisher. Struggling for Public Spaces 41 The Political Significance of Manila’s The National Library of the Philippines CIP Data Segregated Urban Landscape Recommended entry: Lukas Kaelin Making sense of the city : public spaces in the Philippines / Sacral Spaces Between Skyscrapers 69 Remmon E. Barbaza, editor. -- Quezon City : Ateneo de Manila University Press, [2019], c2019. Fernando N. Zialcita pages ; cm Cleaning the Capital 95 ISBN 978-971-550-911-4 The Campaign against Cabarets and Cockpits in the Prewar Greater Manila Area 1. -

Tower One and Exchange Plaza Ayala Triangle, Ayala Avenue, Makati City

July 1, 2011 Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc. Tower One and Exchange Plaza Ayala Triangle, Ayala Avenue, Makati City Attention: Ms. Janet A. Encarnacion Head, Disclosure Department Gentlemen: We are submitting herewith the attached Annual Stockholders List as of June 29, 2011. Very truly yours, GEOFFREY L. UYMATIAO Treasurer Stock Transfer Service Inc. Page No. 1 LEISURE & RESORTS WORLD CORP. (FORMERLY ATLAS FERTILIZER) Stockholder MasterList As of 06/29/2011 Sth. No. Name Address Citizenship Holdings ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 0000041681 AB LEISURE EXPONENT, INC. 26TH FLOOR WEST TOWER, Filipino 16,472,500 PSE BUILDING, ORTIGAS CENTER, PASIG CITY 0000000008 JOSE ABAD C/O ATLAS FERTILIZER CORP. Filipino 487 0000000009 DIOSDADA C. ABANALO CABALLERO SUBD SAN CARLOS CITY LEYTE Filipino 487 0000000007 ISABELO N. ABATAYO TOLEDO CITY Filipino 487 0000000006 BENJAMIN ABAYA 9 STERLING AVE PAMPLONA LAS PINAS MM Filipino 1,296 0000000028 LEONILO J. ABCEDE AFC 38 M. M. CUENCO AVE CEBU CITY Filipino 3,207 0000000027 ALBERTO ABELLA C/O TESSIE RAMIREZ 5/F P & L BLDG LEGASPI ST Filipino 487 MAKATI CITY 0000000037 SATURNINO ABELLA C/O TESSIE RAMIREZ 5/F P & L BLDG LEGASPI ST Filipino 487 MAKATI 0000000005 BENIGNO ABELLANA A. BONIFACIO ST., BAYBAY, LEYTE Filipino 5,063 0000000055 MANUEL G. ABELLO 699 BUFFALO ST., MANDALUYONG, M.M. Filipino 369 0000000065 OCTAVIO ABERION 4 EVENING GLOW BLUE RIDGE QUEZON CITY Filipino 2,090 0000000090 JASMIN M. ABINALES ASD MARKETING CORP., 904 PBCOM BLDG. Filipino 6,802 6795 AYALA AVE MAKATI CITY 0000000170 DIANA M. ABOITIZ P. O. BOX 65, CEBU CITY Filipino 829 0000000205 ENRIQUE M. ABOITIZ P.O. BOX 65, CEBU CITY Filipino 32,508 0000000210 ENRIQUE M. -

9& Pl'ulipptne

9& Pl'ulipptnE. cEtatl~tlalan <?l!ptem&£'lJ 1959 VOL.VIIJ NO.3 , UN'VE~!':'TY OF THE PHrLTPP'NI. fIAn:::>TtC~!= .(.;_~TE.R LlflBA8~ _lSecond Class Mail Matter at the .Manila Post Office on August 25. 19liS THE PHILIPPINE STATISTICIAN Entered as Second Class Mail Matter at the Manila Post Office on August2ii.1953 Published Quarterly by the Philippine Statistical Association Incorporated EDITORIAL BOARD Editor Associate Editor Perfecto R. Franche Lagrimas V. Abalos Annual Subscription - Four Pesos - One Peso per issu Philippines and Foreign Countries The Editors welcome the submission of manuscripts theoretical and applied statistics for possible publication. ~~~~~i~~ds~~~~~n~~st;&~cl1t~eent:~~e~. tu~~s~c~~ p~, The Phlllppine Statistical AsSociation Is Dot respon ts~ :fell'J::d s:d;,:~:s O~e~ain:I:S e:~~~:. ~utte in The I'hiUpptne Statistician. The authors of addresses papers assume sole responsibiUty. Office of Publication 1046 Vergara, Quiapo, Manila P.O. Box 3223 PHILIPPINE STATISTICAL ASSOCIATION Incorporated P. O. Box 3223, Manila BOARD OF DIRECTORS For the Year 1959 OFFICERS President....... .. Manuel O. Hizon First Yice-Ptesident.... Bernardino G. Banteguj Second Vice-President... .. Leon Ma. Gonzales Secretary-Treasurer... Bernardino A. Perez DIRECTORS Paz B. Culabutan perfecto R. Franche Cesar M; Lorenzo ExequieI S. Sevilla Enrique T. Virata PAST PRESIDENTS 1. Cesar M. Lorenzo 1951-1955 2. Enrique T. Virata 1956 3. Exequiel S. Sevilla 1957 152 THE PHILIPPINE STATISTICIAN Official Journal of the Philippine Statistical Association, Incorporated CONTENTS September, 1959 population Increase and Geographical Distribution in the Philippines 154 John J. Carroll, S. J. The Problem of Underemployment in the Philippines 176 Perfecto R.Franche ;Problems of Developing Urban and Rural Definitions for Philippine Population Statistics 185 Bernardino A. -

Filipino Generations in a Changing Landscape ⎮ 281

⎮ 281 ⎮ i FILIPINO GENERATIONS IN A CHANGING LANDSCAPE ⎮ 281 ⎮ iii FILIPINO GENERATIONS IN A CHANGING LANDSCAPE edited by AMARYLLIS T. TORRES, LAURA L. SAMSON AND MANUEL P. DIAZ Philippine Social Science Council 2015 Copyright 2015 by the Philippine Social Science Council (PSSC) PSSCenter, Commonwealth Avenue Diliman, Quezon City Philippines All rights reserved. Inquiries on the reproduction of sections of this volume should be addressed to: Philippine Social Science Council (PSSC) PSSCenter, Commonwealth Avenue Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines email: [email protected] The National Library of the Philippines CIP Data Recommended entry: Filipino generations in a changing landscape / edited by Amaryllis T. Torres, Laura L. Samson and Manuel P. Diaz. -- Diliman, Quezon City : Philippine Social Science Council, [c2015]. p. ; cm ISBN 978-971-8514-36-8 1. Social change -- Philippines. 2. Philippines -- Social condition. I. Torres, Amaryllis T. II. Samson, Laura L. III. Diaz, Manuel P. 303.4 HM831 2015 P520150132 Editors: Amaryllis T. Torres, Laura L. Samson and Manuel P. Diaz Cover design: Mary Jo Candice B. Salumbides Book design and layout: Karen B. Barrios CONTENTS Introduction: Filipino Generations in a Changing Landscape vii Amaryllis T. Torres Generations: The Tyranny of Expectations 1 Randolf S. David Three Generations of Iraya Mangyans: Roles and Dilemmas in the Modern World 9 Aleli B. Bawagan Palaweños, Do We Know Where We’re Going To?: The Dynamics of Generations Y and Z 27 Lorizza Mae C. Posadas and Rowena G. Fernandez Tsinoy in Puerto Princesa: From the American Period to Contemporary Times, a Story of Two Generations 48 Michael Angelo A. Doblado and Oscar L.