Gaming the School Choice Mechanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Labsi Working Papers

UNIVERSITY OF SIENA S.N. O’ H iggins Arturo Palomba Patrizia Sbriglia Second Mover Advantage and Bertrand Dynamic Competition: An Experiment May 2010 LABSI WORKING PAPERS N. 28/2010 SECOND MOVER ADVANTAGE AND BERTRAND DYNAMIC COMPETITION: AN EXPERIMENT § S.N. O’Higgins University of Salerno [email protected] Arturo Palomba University of Naples II [email protected] Patrizia Sbriglia §§ University of Naples II [email protected] Abstract In this paper we provide an experimental test of a dynamic Bertrand duopolistic model, where firms move sequentially and their informational setting varies across different designs. Our experiment is composed of three treatments. In the first treatment, subjects receive information only on the costs and demand parameters and on the price’ choices of their opponent in the market in which they are positioned (matching is fixed); in the second and third treatments, subjects are also informed on the behaviour of players who are not directly operating in their market. Our aim is to study whether the individual behaviour and the process of equilibrium convergence are affected by the specific informational setting adopted. In all treatments we selected students who had previously studied market games and industrial organization, conjecturing that the specific participants’ expertise decreased the chances of imitation in treatment II and III. However, our results prove the opposite: the extra information provided in treatment II and III strongly affects the long run convergence to the market equilibrium. In fact, whilst in the first session, a high proportion of markets converge to the Nash-Bertrand symmetric solution, we observe that a high proportion of markets converge to more collusive outcomes in treatment II and more competitive outcomes in treatment III. -

1 Sequential Games

1 Sequential Games We call games where players take turns moving “sequential games”. Sequential games consist of the same elements as normal form games –there are players, rules, outcomes, and payo¤s. However, sequential games have the added element that history of play is now important as players can make decisions conditional on what other players have done. Thus, if two people are playing a game of Chess the second mover is able to observe the …rst mover’s initial move prior to making his initial move. While it is possible to represent sequential games using the strategic (or matrix) form representation of the game it is more instructive at …rst to represent sequential games using a game tree. In addition to the players, actions, outcomes, and payo¤s, the game tree will provide a history of play or a path of play. A very basic example of a sequential game is the Entrant-Incumbent game. The game is described as follows: Consider a game where there is an entrant and an incumbent. The entrant moves …rst and the incumbent observes the entrant’sdecision. The entrant can choose to either enter the market or remain out of the market. If the entrant remains out of the market then the game ends and the entrant receives a payo¤ of 0 while the incumbent receives a payo¤ of 2. If the entrant chooses to enter the market then the incumbent gets to make a choice. The incumbent chooses between …ghting entry or accommodating entry. If the incumbent …ghts the entrant receives a payo¤ of 3 while the incumbent receives a payo¤ of 1. -

Finitely Repeated Games

Repeated games 1: Finite repetition Universidad Carlos III de Madrid 1 Finitely repeated games • A finitely repeated game is a dynamic game in which a simultaneous game (the stage game) is played finitely many times, and the result of each stage is observed before the next one is played. • Example: Play the prisoners’ dilemma several times. The stage game is the simultaneous prisoners’ dilemma game. 2 Results • If the stage game (the simultaneous game) has only one NE the repeated game has only one SPNE: In the SPNE players’ play the strategies in the NE in each stage. • If the stage game has 2 or more NE, one can find a SPNE where, at some stage, players play a strategy that is not part of a NE of the stage game. 3 The prisoners’ dilemma repeated twice • Two players play the same simultaneous game twice, at ! = 1 and at ! = 2. • After the first time the game is played (after ! = 1) the result is observed before playing the second time. • The payoff in the repeated game is the sum of the payoffs in each stage (! = 1, ! = 2) • Which is the SPNE? Player 2 D C D 1 , 1 5 , 0 Player 1 C 0 , 5 4 , 4 4 The prisoners’ dilemma repeated twice Information sets? Strategies? 1 .1 5 for each player 2" for each player D C E.g.: (C, D, D, C, C) Subgames? 2.1 5 D C D C .2 1.3 1.5 1 1.4 D C D C D C D C 2.2 2.3 2 .4 2.5 D C D C D C D C D C D C D C D C 1+1 1+5 1+0 1+4 5+1 5+5 5+0 5+4 0+1 0+5 0+0 0+4 4+1 4+5 4+0 4+4 1+1 1+0 1+5 1+4 0+1 0+0 0+5 0+4 5+1 5+0 5+5 5+4 4+1 4+0 4+5 4+4 The prisoners’ dilemma repeated twice Let’s find the NE in the subgames. -

Chapter 16 Oligopoly and Game Theory Oligopoly Oligopoly

Chapter 16 “Game theory is the study of how people Oligopoly behave in strategic situations. By ‘strategic’ we mean a situation in which each person, when deciding what actions to take, must and consider how others might respond to that action.” Game Theory Oligopoly Oligopoly • “Oligopoly is a market structure in which only a few • “Figuring out the environment” when there are sellers offer similar or identical products.” rival firms in your market, means guessing (or • As we saw last time, oligopoly differs from the two ‘ideal’ inferring) what the rivals are doing and then cases, perfect competition and monopoly. choosing a “best response” • In the ‘ideal’ cases, the firm just has to figure out the environment (prices for the perfectly competitive firm, • This means that firms in oligopoly markets are demand curve for the monopolist) and select output to playing a ‘game’ against each other. maximize profits • To understand how they might act, we need to • An oligopolist, on the other hand, also has to figure out the understand how players play games. environment before computing the best output. • This is the role of Game Theory. Some Concepts We Will Use Strategies • Strategies • Strategies are the choices that a player is allowed • Payoffs to make. • Sequential Games •Examples: • Simultaneous Games – In game trees (sequential games), the players choose paths or branches from roots or nodes. • Best Responses – In matrix games players choose rows or columns • Equilibrium – In market games, players choose prices, or quantities, • Dominated strategies or R and D levels. • Dominant Strategies. – In Blackjack, players choose whether to stay or draw. -

Cooperation Spillovers in Coordination Games*

Cooperation Spillovers in Coordination Games* Timothy N. Casona, Anya Savikhina, and Roman M. Sheremetab aDepartment of Economics, Krannert School of Management, Purdue University, 403 W. State St., West Lafayette, IN 47906-2056, U.S.A. bArgyros School of Business and Economics, Chapman University, One University Drive, Orange, CA 92866, U.S.A. November 2009 Abstract Motivated by problems of coordination failure observed in weak-link games, we experimentally investigate behavioral spillovers for order-statistic coordination games. Subjects play the minimum- and median-effort coordination games simultaneously and sequentially. The results show the precedent for cooperative behavior spills over from the median game to the minimum game when the games are played sequentially. Moreover, spillover occurs even when group composition changes, although the effect is not as strong. We also find that the precedent for uncooperative behavior does not spill over from the minimum game to the median game. These findings suggest guidelines for increasing cooperative behavior within organizations. JEL Classifications: C72, C91 Keywords: coordination, order-statistic games, experiments, cooperation, minimum game, behavioral spillover Corresponding author: Timothy Cason, [email protected] * We thank Yan Chen, David Cooper, John Duffy, Vai-Lam Mui, seminar participants at Purdue University, and participants at Economic Science Association conferences for helpful comments. Any remaining errors are ours. 1. Introduction Coordination failure is often the reason for the inefficient performance of many groups, ranging from small firms to entire economies. When agents’ actions have strategic interdependence, even when they succeed in coordinating they may be “trapped” in an equilibrium that is objectively inferior to other equilibria. Coordination failure and inefficient coordination has been an important theme across a variety of fields in economics, ranging from development and macroeconomics to mechanism design for overcoming moral hazard in teams. -

570: Minimax Sample Complexity for Turn-Based Stochastic Game

Minimax Sample Complexity for Turn-based Stochastic Game Qiwen Cui1 Lin F. Yang2 1School of Mathematical Sciences, Peking University 2Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, University of California, Los Angeles Abstract guarantees are rather rare due to complex interaction be- tween agents that makes the problem considerably harder than single agent reinforcement learning. This is also known The empirical success of multi-agent reinforce- as non-stationarity in MARL, which means when multi- ment learning is encouraging, while few theoret- ple agents alter their strategies based on samples collected ical guarantees have been revealed. In this work, from previous strategy, the system becomes non-stationary we prove that the plug-in solver approach, proba- for each agent and the improvement can not be guaranteed. bly the most natural reinforcement learning algo- One fundamental question in MBRL is that how to design rithm, achieves minimax sample complexity for efficient algorithms to overcome non-stationarity. turn-based stochastic game (TBSG). Specifically, we perform planning in an empirical TBSG by Two-players turn-based stochastic game (TBSG) is a two- utilizing a ‘simulator’ that allows sampling from agents generalization of Markov decision process (MDP), arbitrary state-action pair. We show that the em- where two agents choose actions in turn and one agent wants pirical Nash equilibrium strategy is an approxi- to maximize the total reward while the other wants to min- mate Nash equilibrium strategy in the true TBSG imize it. As a zero-sum game, TBSG is known to have and give both problem-dependent and problem- Nash equilibrium strategy [Shapley, 1953], which means independent bound. -

Formation of Coalition Structures As a Non-Cooperative Game

Formation of coalition structures as a non-cooperative game Dmitry Levando, ∗ Abstract We study coalition structure formation with intra and inter-coalition externalities in the introduced family of nested non-cooperative si- multaneous finite games. A non-cooperative game embeds a coalition structure formation mechanism, and has two outcomes: an alloca- tion of players over coalitions and a payoff for every player. Coalition structures of a game are described by Young diagrams. They serve to enumerate coalition structures and allocations of players over them. For every coalition structure a player has a set of finite strategies. A player chooses a coalition structure and a strategy. A (social) mechanism eliminates conflicts in individual choices and produces final coalition structures. Every final coalition structure is a non-cooperative game. Mixed equilibrium always exists and consists arXiv:2107.00711v1 [cs.GT] 1 Jul 2021 of a mixed strategy profile, payoffs and equilibrium coalition struc- tures. We use a maximum coalition size to parametrize the family ∗Moscow, Russian Federation, independent. No funds, grants, or other support was received. Acknowledge: Nick Baigent, Phillip Bich, Giulio Codognato, Ludovic Julien, Izhak Gilboa, Olga Gorelkina, Mark Kelbert, Anton Komarov, Roger Myerson, Ariel Rubinstein, Shmuel Zamir. Many thanks for advices and for discussion to participants of SIGE-2015, 2016 (an earlier version of the title was “A generalized Nash equilibrium”), CORE 50 Conference, Workshop of the Central European Program in Economic Theory, Udine (2016), Games 2016 Congress, Games and Applications, (2016) Lisbon, Games and Optimization at St Etienne (2016). All possible mistakes are only mine. E-mail for correspondence: dlevando (at) hotmail.ru. -

Finding Strategic Game Equivalent of an Extensive Form Game

Finding Strategic Game Equivalent of an Extensive Form Game • In an extensive form game, a strategy for a player should specify what action the player will choose at each information set. That is, a strategy is a complete plan for playing a game for a particular player. • Therefore to find the strategic game equivalent of an extensive form game we should follow these steps: 1. First we need to find all strategies for every player. To do that first we find all information sets for every player (including the singleton information sets). If there are many of them we may label them (such as Player 1’s 1st info. set, Player 1’s 2nd info. set, etc.) 2. A strategy should specify what action the player will take in every information set which belongs to him/her. We find all combinations of actions the player can take at these information sets. For example if a player has 3 information sets where • the first one has 2 actions, • the second one has 2 actions, and • the third one has 3 actions then there will be a total of 2 × 2 × 3 = 12 strategies for this player. 3. Once the strategies are obtained for every player the next step is finding the payoffs. For every strategy profile we find the payoff vector that would be obtained in case these strategies are played in the extensive form game. Example: Let’s find the strategic game equivalent of the following 3-level centipede game. (3,1)r (2,3)r (6,2)r (4,6)r (12,4)r (8,12)r S S S S S S r 1 2 1 2 1 2 (24,8) C C C C C C 1. -

How to Solve Strategic Games? Dominant Strategies

How to Solve Strategic Games? There are three main concepts to solve strategic games: 1. Dominant Strategies & Dominant Strategy Equilibrium 2. Dominated Strategies & Iterative Elimination of Dominated Strategies 3. Nash Equilibrium Dominant Strategies • Astrategyisadominant strategy for a player if it yields the best payoff (for that player) no matter what strategies the other players choose. • If all players have a dominant strategy, then it is natural for them to choose the dominant strategies and we reach a dominant strategy equilibrium. Example (Prisoner’s Dilemma): Prisoner 2 Confess Deny Prisoner 1 Confess -10, -10 -1, -25 Deny -25, -1 -3, -3 Confess is a dominant strategy for both players and therefore (Confess,Confess) is a dominant strategy equilibrium yielding the payoff vector (-10,-10). Example (Time vs. Newsweek): Newsweek AIDS BUDGET Time AIDS 35,35 70,30 BUDGET 30,70 15,15 The AIDS story is a dominant strategy for both Time and Newsweek. Therefore (AIDS,AIDS) is a dominant strategy equilibrium yielding both magazines a market share of 35 percent. Example: Player 2 XY A 5,2 4,2 Player 1 B 3,1 3,2 C 2,1 4,1 D 4,3 5,4 • Here Player 1 does not have a single strategy that “beats” every other strategy. Therefore she does not have a dominant strategy. • On the other hand Y is a dominant strategy for Player 2. Example (with 3 players): P3 A B P2 P2 LR LR U 3,2,1 2,1,1 U 1,1,2 2,0,1 P1 M 2,2,0 1,2,1 M 1,2,0 1,0,2 D 3,1,2 1,0,2 D 0,2,3 1,2,2 Here • U is a dominant strategy for Player 1, L is a dominant strategy for Player 2, B is a dominant strategy for Player 3, • and therefore (U;L;B) is a dominant strategy equilibrium yielding a payoff of (1,1,2). -

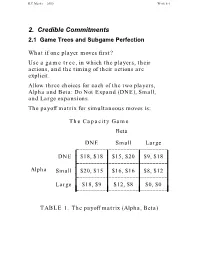

Credible Commitments 2.1 Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-1 2. Credible Commitments 2.1 Game Trees and Subgame Perfection What if one player moves first? Use a game tree, in which the players, their actions, and the timing of their actions are explicit. Allow three choices for each of the two players, Alpha and Beta: Do Not Expand (DNE), Small, and Large expansions. The payoff matrix for simultaneous moves is: The Capacity Game Beta ________________________________DNE Small Large L L L L DNE $18, $18 $15, $20 $9, $18 _L_______________________________L L L L L L L Alpha SmallL $20, $15L $16, $16L $8, $12 L L________________________________L L L L L L L Large_L_______________________________ $18, $9L $12, $8L $0, $0 L TABLE 1. The payoff matrix (Alpha, Beta) R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-2 The game tree. If Alpha preempts Beta, by making its capacity decision before Beta does, then use the game tree: Alpha L S DNE Beta Beta Beta L S DNE L S DNE L S DNE 0 12 18 8 16 20 9 15 18 0 8 9 12 16 15 18 20 18 Figure 1. Game Tree, Payoffs: Alpha’s, Beta’s Use subgame perfect Nash equilibrium, in which each player chooses the best action for itself at each node it might reach, and assumes similar behaviour on the part of the other. R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-3 2.1.1 Backward Induction With complete information (all know what each has done), we can solve this by backward induction: 1. From the end (final payoffs), go up the tree to the first parent decision nodes. -

Section Note 3

Section Note 3 Ariella Kahn-Lang and Guthrie Gray-Lobe∗ February 13th 2013 Agenda 1. Game Trees 2. Writing out Strategies and the Strategy Space 3. Backwards Induction 1 Game Trees Let's review the basic elements of game trees (extensive form games). Remember, we can write any game in either its normal (matrix) form or its extensive (tree) form - which representation we use is mainly a question of which solution concept we want to implement. Game trees are particularly useful for representing dynamic (sequential) games, primarily be- cause they easily allow us to implement the simple solution concept of backwards induction (see later). 1.1 Dynamic Games vs. Simultaneous Games Many important economic applications in game theory cannot be described by a simultaneous move game. Recall that a simultaneous game is one where all players were choosing their actions without any information about actions chosen by other players. A dynamic game, in contrast, is one where at least one player at some point of the game is choosing his action with some information about actions chosen previously. While dynamic games are often sequential over time, what matters is not the timing, but the information a player holds about previous moves in the game, because this is what enables them to condition their strategy on previous moves. For this reason, the `order' in which we draw a game tree matters only in getting the flow of information correctly. In simultaneous games, we can draw the game tree either way round and it represents the same game. ∗Thanks to previous years' TF's for making their section materials available for adaptation. -

1.5 Nash Equilibrium

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Department of Management and Production Engineering Master Degree in Engineering and Management Thesis Neuroeconomics: how neuroscience can impact game theory Supervisor: Candidate: prof. Luigi Buzzacchi Francesca Vallomy Academic Year 2019/2020 1 Index INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER I - TRADITIONAL GAME THEORY 6 1.1 AREAS OF APPLICATION OF GAME THEORY 7 1.2 GAME DEFINITION 9 1.2.1 INFORMATION 11 1.2.2 TIME 12 1.2.3 REPRESENTATION 13 1.2.4 CONSTANT AND VARIABLE SUM 14 1.2.5 COOPERATION 15 1.2.6 EQUILIBRIUM 16 1.2.7 DOMINANCE CRITERIA 17 1.3 PRECURSORS OF GAME THEORY 19 1.4 THEORY OF GAMES AND ECONOMIC BEHAVIOR 22 1.4.1 MINIMAX THEOREM 22 1.5 NASH EQUILIBRIUM 26 1.5.1 DEFINITION OF BEST RESPONSE 27 1.5.2 DEFINITION OF NASH EQUILIBRIUM 27 1.5.3 PRISONER’S DILEMMA 28 1.5.4 REPEATED GAME 31 1.5.4.1 Strategies in a repeated game 33 1.5.4.1.1 Tit-for-tat strategy 33 1.5.4.1.2 Grim strategy 33 1.5.4.2 Repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma 34 1.5.4.3 Reputation in Repeated Games 35 1.5.5 PARETO OPTIMALITY 36 1.5.6 LIMITATIONS OF NASH EQUILIBRIUM 38 1.6 THEORY OF RATIONAL CHOICE 39 1.7 GAMES ACCORDING TO RATIONAL THEORY 44 1.7.1 ULTIMATUM GAME 44 1.7.2 TRUST GAME 46 CHAPTER II - LIMITATIONS OF TRADITIONAL GAME THEORY AND BEHAVIOURAL GAME THEORY 47 2.1 DRAWBACKS OF TRADITIONAL GAME THEORY 48 2.1.1 NASH EQUILIBRIUM INEFFICIENCY 48 2.1.2 GAMES WITH MULTIPLE NASH EQUILIBRIA 53 2.2 DRAWBACKS OF THE THEORY OF RATIONAL CHOICE 55 2.2.1 INTERNAL LIMITATIONS OF THE THEORY OF RATIONAL CHOICE 58 2.2.2 GENERAL LIMITATIONS OF THE THEORY OF RATIONAL CHOICE