Hosting Web Communities: Building Relationships, Increasing Customer Loyalty, and Maintaining a Competitive Edge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henning Schulzrinne Julian Clarence Levi Professor Work Phone: +1 212

Henning Schulzrinne Julian Clarence Levi Professor work phone: +1 212 939 7042 Dept. of Computer Science fax: +1 212 666 0140 Columbia University email: [email protected] New York, NY 10027 WWW: http://www.cs.columbia.edu/˜hgs USA SIP: sip:[email protected] INTERESTS Internet multimedia, policy, services, architecture, computer networks and performance evaluation. Telecommunication policy; Internet telephony, collaboration and media-on- demand; Internet of things; emergency services; signaling and session control; mobile ap- plications; ubiquitous and pervasive computing; network measurements; quality of service; Internet protocols and services; congestion control and adaptive multimedia services; im- plementations of multi-media and real-time networks; operating system support for high- bandwidth services with real-time constraints; performance analysis of computer networks and systems. WORK EXPERIENCE Technology Fellow, Senator Ron Wyden (U.S. Senate), September 2019–August 2020. Chief Technology Officer, Federal Communications Commission (FCC), January 2017– August 2017. Senior Advisor for Technology, Federal Communications Commission (FCC), September 2016–December 2016. Technology Advisor, Federal Communications Commission (FCC), September 2014–August 2016. Chief Technology Officer, Federal Communications Commission (FCC), January 2012– August 2014. Engineering Fellow, Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Sept. 2010–May 2011. Professor (tenured), Dept. of Computer Science and Dept. of Electrical Engineering (joint appointment), Columbia University. August 1996–. Department vice chair, 2002– 2003; Department chair, 2004–2009. Researcher, GMD Fokus1, Berlin, Germany. March 1994 - July 1996. Multimedia sys- tems, ATM performance issues. Deputy department head; project leader TOMQAT, Multicube, MMTng. Lecturer at Technical University Berlin. Consultant, 1994-1996: design and implementation of an Internet packet audio tool for a WWW-based “Virtual Places” shared environment (Ubique, Israel). -

A Perfectly Good Hour

A PERFECTLY GOOD HOUR 1. Social Capital 2. Social Intelligence 3. Listening 4. Identity 5. Language & Cursing 6. Nonverbal Communication 7. Satisfying Relationships 8. Consummate Love 9. Conflict Management 10. Styles of Parenting/Leading Modern Social Commentary Cartoons by David Hawker from PUNCH Magazine, 1981 A PERFECTLY GOOD HOUR Feel free to voice your opinion and to disagree. This is not a friction- free zone. AND, please do demonstrate social intelligence. Let’s Get Better Acquainted If you match this descriptor, keep your 1. You belong to an LLI Special Interest Group video on and unmute. 2. You are fluent in another language 3. You’ve received your flu shot If you don’t match this 4. You attended the LLI class on nanotechnology descriptor, temporarily 5. You have grandchildren stop your video. 6. You (have) participate(d) in Great Decisions 7. You have a pet 8. You play a musical instrument 9. You are/have been on the LLI Board 10. You think this is a fun poll How fortunate we are that during this global pandemic, we can stay home, attending LLI classes, reading, creating, baking, taking walks, and talking with our loved one. The last six months have exposed and magnified long standing inequities -- in our communities, in our hospitals, in our workplaces, and in schools. Too many of our school districts lack a fair share of resources to address the pandemic’s challenges; not every student can be taught remotely with attention to their need for social and emotional safe learning spaces. The current circumstances are poised to exacerbate existing disparities in academic opportunity and performance, particularly between white communities and communities of color. -

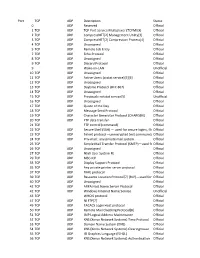

List of TCP and UDP Port Numbers from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

List of TCP and UDP port numbers From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This is a list of Internet socket port numbers used by protocols of the transport layer of the Internet Protocol Suite for the establishment of host-to-host connectivity. Originally, port numbers were used by the Network Control Program (NCP) in the ARPANET for which two ports were required for half- duplex transmission. Later, the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) needed only one port for full- duplex, bidirectional traffic. The even-numbered ports were not used, and this resulted in some even numbers in the well-known port number /etc/services, a service name range being unassigned. The Stream Control Transmission Protocol database file on Unix-like operating (SCTP) and the Datagram Congestion Control Protocol (DCCP) also systems.[1][2][3][4] use port numbers. They usually use port numbers that match the services of the corresponding TCP or UDP implementation, if they exist. The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) is responsible for maintaining the official assignments of port numbers for specific uses.[5] However, many unofficial uses of both well-known and registered port numbers occur in practice. Contents 1 Table legend 2 Well-known ports 3 Registered ports 4 Dynamic, private or ephemeral ports 5 See also 6 References 7 External links Table legend Official: Port is registered with IANA for the application.[5] Unofficial: Port is not registered with IANA for the application. Multiple use: Multiple applications are known to use this port. Well-known ports The port numbers in the range from 0 to 1023 are the well-known ports or system ports.[6] They are used by system processes that provide widely used types of network services. -

By CARLTON A. THOMPSON a DISSERTATION

A DESIGN AND PERFORMANCE STUDY OF A DISTRIBUTED IP-BASED TELECOMMUNICATION SYSTEM (D-IPTS) By CARLTON A. THOMPSON A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Carlton A. Thompson 2 To my mother Hyacinth Thompson and to the memory of my father Carlton Thompson, for always supporting me during my studies and work. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The path to PhD has been very challenging and I have achieved a milestone in my career. I learned a lot about the field of IP telecommunications, peformance analysis, and associated qualitative research methods. This dissertation would not have been written without the help of certain individuals. I would like to extend my gratitude towards my advisor Dr. Latchman and co-advisor Dr. McNair. They helped me with the selection of my topic and provided guidance during the writing of my dissertation. Their encouragement and insights have always been inspiring. In addition, none of this could have been possible without my family and loved ones providing their continuous support during my various course studies. Also, I would like to thank my friends and colleagues from the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department at the University of Florida. Finally, I would like to thank Texas Instruments ™ for providing financial support for this work. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..................................4 LIST OF TABLES......................................9 LIST OF FIGURES..................................... 10 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................ 14 ABSTRACT......................................... 17 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .................................... 19 Motivation........................................ 20 Voice Networks..................................... 21 Traditional Telecommunications Networks.................. -

How Do Tor Users Interact with Onion Services?

How Do Tor Users Interact With Onion Services? Philipp Winter Anne Edmundson Laura M. Roberts Princeton University Princeton University Princeton University Agnieszka Dutkowska-Zuk˙ Marshini Chetty Nick Feamster Independent Princeton University Princeton University Abstract messaging [4] and file sharing [15]. The Tor Project currently does not have data on the number of onion Onion services are anonymous network services that are service users, but Facebook reported in 2016 that more exposed over the Tor network. In contrast to conventional than one million users logged into its onion service in one Internet services, onion services are private, generally not month [20]. indexed by search engines, and use self-certifying domain Onion services differ from conventional web services names that are long and difficult for humans to read. In in four ways; First, they can only be accessed over the Tor this paper, we study how people perceive, understand, and network. Second, onion domains are hashes over their use onion services based on data from 17 semi-structured public key, which make them difficult to remember. Third, interviews and an online survey of 517 users. We find that the network path between client and the onion service is users have an incomplete mental model of onion services, typically longer, increasing latency and thus reducing the use these services for anonymity and have varying trust in performance of the service. Finally, onion services are onion services in general. Users also have difficulty dis- private by default, meaning that users must discover these covering and tracking onion sites and authenticating them. sites organically, rather than with a search engine. -

A Standard Path Towards Scalable Conferencing in the Internet Alessandro Amirante Ph.D

Facolt`adi Ingegneria Dottorato di Ricerca in Ingegneria Informatica ed Automatica XXIII Ciclo Dipartimento di Informatica e Sistemistica A standard path towards scalable conferencing in the Internet Alessandro Amirante Ph.D. Thesis Tutor Coordinator Prof. Simon Pietro Romano Prof. Francesco Garofalo Co-tutor Prof. Henning Schulzrinne November 2010 Abstract The work described in this Ph.D. thesis has been carried out within the con- text of computer networks and real-time multimedia applications over the Internet. Specifically, we focus on conferencing, a challenging service which experienced a wide growth during the last years. We examine the standard- ization efforts conducted in this field by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), which are mainly focused on centralized conferencing as defined by the XCON Working Group. We actively contributed to such efforts by de- signing and implementing the defined framework and protocols, while also writing best current practice documents which are on the path to become Re- quest For Comments (RFCs). The main outcome of such activities has been Meetecho, a standards-compliant multimedia conferencing and collaboration platform we developed. Meetecho has been conceived at the outset to be ex- tensible towards a distributed architecture, yet being fully compliant with the XCON specification, in order to better fulfill scalability requirements re- sulting from its large-scale deployment. The distributed architecture, which is the subject of the DCON (Distributed Conferencing) proposal we submit- ted to the IETF, is thoroughly described herein, where we also provide the reader with the results of a scalability analysis we conducted in order to as- sess the actual performance improvement attainable with distribution. -

Real-Time Communications Quick Start Guide

Real-Time Communications Quick Start Guide Daniel Pocock [http://danielpocock.com] Real-Time Communications Quick Start Guide Daniel Pocock [http://danielpocock.com] Copyright © 2013, 2014, 2015 Daniel Pocock Table of Contents Preface ........................................................................................................................ x 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Federation ............................................................................................................ 1 Independent and decentralized alternatives to federation ............................................... 1 Private networks ........................................................................................... 1 Decentralized networks .................................................................................. 1 Conclusion ................................................................................................... 2 Choosing between SIP and XMPP ........................................................................... 2 Choice of operating system ..................................................................................... 3 Using a ready-to-run or turn-key solution .......................................................... 3 Using a generic GNU/Linux distribution ........................................................... 3 Use latest software versions ................................................................................... -

Official 2 TCP UDP Compr

Port TCP UDP Description Status 0 UDP Reserved Official 1 TCP UDP TCP Port Service Multiplexer (TCPMUX) Official 2 TCP UDP CompressNET[2] Management Utility[3] Official 3 TCP UDP CompressNET[2] Compression Process[4] Official 4 TCP UDP Unassigned Official 5 TCP UDP Remote Job Entry Official 7 TCP UDP Echo Protocol Official 8 TCP UDP Unassigned Official 9 TCP UDP Discard Protocol Official 9 UDP Wake-on-LAN Unofficial 10 TCP UDP Unassigned Official 11 TCP UDP Active Users (systat service)[5][6] Official 12 TCP UDP Unassigned Official 13 TCP UDP Daytime Protocol (RFC 867) Official 14 TCP UDP Unassigned Official 15 TCP UDP Previously netstat service[5] Unofficial 16 TCP UDP Unassigned Official 17 TCP UDP Quote of the Day Official 18 TCP UDP Message Send Protocol Official 19 TCP UDP Character Generator Protocol (CHARGEN) Official 20 TCP UDP FTP data transfer Official 21 TCP FTP control (command) Official 22 TCP UDP Secure Shell (SSH) — used for secure logins, file Officialtransfers (scp, sftp) and port forwarding 23 TCP UDP Telnet protocol—unencrypted text communicationsOfficial 24 TCP UDP Priv-mail : any private mail system. Official 25 TCP Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP)—used forOfficial e-mail routing between mail servers 26 TCP UDP Unassigned Official 27 TCP UDP NSW User System FE Official 29 TCP UDP MSG ICP Official 33 TCP UDP Display Support Protocol Official 35 TCP UDP Any private printer server protocol Official 37 TCP UDP TIME protocol Official 39 TCP UDP Resource Location Protocol*7+ (RLP)—used for determiningOfficial the location -

9.3 Asynchronous Distributed Interfaces

6546_Shneiderman_CH09_p358-402.qxd 1/16/09 12:00 PM Page 358 2nd Proof 6546_Shneiderman_CH09_p358-402.qxd 1/16/09 12:00 PM Page 359 CHAPTER Collaboration and Social Media Participation Three helping one another will do as ‘‘ much as six working singly.’’ Spanish Proverb Written in collaboration with Maxine S. Cohen 2nd Proof 6546_Shneiderman_CH09_p358-402.qxd 1/16/09 12:00 PM Page 360 360CHAPTER OUTLINE 9.1 Introduction 9.2 Goals of Collaboration and Participation 9.3 Asynchronous Distributed Interfaces: Different Place, Different Time 9.4 Synchronous Distributed Interfaces: Different Place, Same Time 9.5 Face-to-Face Interfaces: Same Place, Same Time 9.1 Introduction The introversion and isolation of early computer users has given way to extremely lively online communities of busily interacting teams and bustling crowds of chatty diverse users that span the gamut in terms of age, computer expertise, and geographic locations. The pursuit of human connections has prompted millions of users to join listservers, visit chat rooms, and fill online communities with useful information and supportive responses, peppered with outrageous humor. But, as in most human communities, there is also contro- versy, anger, slander, and pornography. The World Wide Web has dramatically enriched textual communications with colorful graphics and sometimes too- dazzling Java or Flash animations. The Web is sometimes derided as a play- ground, but serious work and creative endeavors are enormously facilitated by the easy flow of information it provides. Cell phones and mobile devices have also expanded the possibilities for communication by voice, text messages, digi- tal photos, videos, and other forms of user-generated content. -

BRAND AVATAR This Page Intentionally Left Blank BRAND AVATAR TRANSLATING VIRTUAL WORLD BRANDING INTO REAL WORLD SUCCESS

BRAND AVATAR This page intentionally left blank BRAND AVATAR TRANSLATING VIRTUAL WORLD BRANDING INTO REAL WORLD SUCCESS Alycia de Mesa © Alycia de Mesa 2009 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2009 978-0-230-20179-8 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2009 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries ISBN 978-1-349-29999-7 ISBN 978-0-230-23371-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230233713 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

OSINT Handbook September 2020

OPEN SOURCE INTELLIGENCE TOOLS AND RESOURCES HANDBOOK 2020 OPEN SOURCE INTELLIGENCE TOOLS AND RESOURCES HANDBOOK 2020 Aleksandra Bielska Noa Rebecca Kurz, Yves Baumgartner, Vytenis Benetis 2 Foreword I am delighted to share with you the 2020 edition of the OSINT Tools and Resources Handbook. Once again, the Handbook has been revised and updated to reflect the evolution of this discipline, and the many strategic, operational and technical challenges OSINT practitioners have to grapple with. Given the speed of change on the web, some might question the wisdom of pulling together such a resource. What’s wrong with the Top 10 tools, or the Top 100? There are only so many resources one can bookmark after all. Such arguments are not without merit. My fear, however, is that they are also shortsighted. I offer four reasons why. To begin, a shortlist betrays the widening spectrum of OSINT practice. Whereas OSINT was once the preserve of analysts working in national security, it now embraces a growing class of professionals in fields as diverse as journalism, cybersecurity, investment research, crisis management and human rights. A limited toolkit can never satisfy all of these constituencies. Second, a good OSINT practitioner is someone who is comfortable working with different tools, sources and collection strategies. The temptation toward narrow specialisation in OSINT is one that has to be resisted. Why? Because no research task is ever as tidy as the customer’s requirements are likely to suggest. Third, is the inevitable realisation that good tool awareness is equivalent to good source awareness. Indeed, the right tool can determine whether you harvest the right information. -

IBM Connections Social Cloud Mobile Features Guide

Sametime & iNotes Integration Guide Declan Joyce Imran Khan IBM Collaboration Solutions, IBM Software Group, Mulhuddart, Ireland Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 iNotes Client Features ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Chat and Awareness ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Buddy List ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 Architecture ...................................................................................................................................................................... 7 How Sametime integrates with iNotes ................................................................................................................ 8 Server Components .............................................................................................................................................. 9 Important URLs ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Configuration Files and Databases ...................................................................................................................