The Poetical Works of Brunton Stephens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Brunton Stephens - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Brunton Stephens - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Brunton Stephens(17 June 1835 – 29 June 1902) James Brunton Stephens was a Scottish-born Australian poet, author of Convict Once. <B>Early life</B> Stephens was born at Borrowstounness, on the Firth of Forth, Scotland; the son of John Stephens, the parish schoolmaster, and his wife Jane, née Brunton. J. B. Stephens was educated at his father's school, then at a free boarding school and at the University of Edinburgh from 1849 to 1854 without obtaining a degree. For three years he was a travelling tutor on the continent, and from 1859 became a school teacher in Scotland. While teaching at Greenock Academy in Greenock, Stephens wrote some minor verse and two short novels ('Rutson Morley' and 'Virtue Le Moyne') which were published in Sharpe's London Magazine in 1861- 63. <B>Career in Australia</b> Stephens migrated to Queensland, Australia, in 1866 possibly for health reasons. He was a tutor with the Barker family of squatters at Tamrookum station for some time and in 1870 entered the Queensland education department. He had experience as a teacher at Stanthorpe and was afterwards in charge of the school at Ashgrove, near Brisbane. Representations were then made to the premier, Sir Thomas McIlwraith, that a man of Stephens's ability was being wasted in a small school, and in 1883 a position was found for him as a correspondence clerk in the colonial secretary's department. He afterwards rose to be undersecretary to the chief secretary's department. -

7 Stars to Morning

7 Stars to Morning By Francis Brabazon An Avatar Meher Baba Trust eBook Copyright © 1956 by Avatar’s Abode Trust Source: 7 Stars to Morning By Francis Brabazon Designed and Produced by Edwards & Shaw for Morgan’s Bookshop 8 Castlereagh Street, Sydney Wholly set up set and printed in Australia Registered at the G.P.O. Sydney for transmission through the post as a book 1956 eBooks at the Avatar Meher Baba Trust Web Site The Avatar Meher Baba Trust's eBooks aspire to be textually exact though non-facsimile reproductions of published books, journals and articles. With the consent of the copyright holders, these online editions are being made available through the Avatar Meher Baba Trust's web site, for the research needs of Meher Baba's lovers and the general public around the world. Again, the eBooks reproduce the text, though not the exact visual likeness, of the original publications. They have been created through a process of scanning the original pages, running these scans through optical character recognition (OCR) software, reflowing the new text, and proofreading it. Except in rare cases where we specify otherwise, the texts that you will find here correspond, page for page, with those of the original publications: in other words, page citations reliably correspond to those of the source books. But in other respects-such as lineation and font-the page designs differ. Our purpose is to provide digital texts that are more readily downloadable and searchable than photo facsimile images of the originals would have been. Moreover, they are often much more readable, especially in the case of older books, whose discoloration and deteriorated condition often makes them partly illegible. -

Edgar Albert Guest - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Edgar Albert Guest - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Edgar Albert Guest(20 August 1881 - 5 August 1959) Edgar Allen Guest also known as Eddie Guest was a prolific English-born American poet who was popular in the first half of the 20th century and became known as the People's Poet. Eddie Guest was born in Birmingham, England in 1881, moving to Michigan USA as a young child, it was here he was educated. In 1895, the year before Henry Ford took his first ride in a motor carriage, Eddie Guest signed on with the Free Press as a 13-year-old office boy. He stayed for 60 years. In those six decades, Detroit underwent half a dozen identity changes, but Eddie Guest became a steadfast character on the changing scene. Three years after he joined the Free Press, Guest became a cub reporter. He quickly worked his way through the labor beat -- a much less consequential beat than it is today -- the waterfront beat and the police beat, where he worked "the dog watch" -- 3 p.m. to 3 a.m. By the end of that year -- the year he should have been completing high school - - Guest had a reputation as a scrappy reporter in a competitive town. It did not occur to Guest to write in verse until late in 1898 when he was working as assistant exchange editor. It was his job to cull timeless items from the newspapers with which the Free Press exchanged papers for use as fillers. -

Vanguard Label Discography Was Compiled Using Our Record Collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1953 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963, and Various Other Sources

Discography Of The Vanguard Label Vanguard Records was established in New York City in 1947. It was owned by Maynard and Seymour Solomon. The label released classical, folk, international, jazz, pop, spoken word, rhythm and blues and blues. Vanguard had a subsidiary called Bach Guild that released classical music. The Solomon brothers started the company with a loan of $10,000 from their family and rented a small office on 80 East 11th Street. The label was started just as the 33 1/3 RPM LP was just gaining popularity and Vanguard concentrated on LP’s. Vanguard commissioned recordings of five Bach Cantatas and those were the first releases on the label. As the long play market expanded Vanguard moved into other fields of music besides classical. The famed producer John Hammond (Discoverer of Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin) came in to supervise a jazz series called Jazz Showcase. The Solomon brothers’ politics was left leaning and many of the artists on Vanguard were black-listed by the House Un-American Activities Committive. Vanguard ignored the black-list of performers and had success with Cisco Houston, Paul Robeson and the Weavers. The Weavers were so successful that Vanguard moved more and more into the popular field. Folk music became the main focus of the label and the home of Joan Baez, Ian and Sylvia, Rooftop Singers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Doc Watson, Country Joe and the Fish and many others. During the 1950’s and early 1960’s, a folk festival was held each year in Newport Rhode Island and Vanguard recorded and issued albums from the those events. -

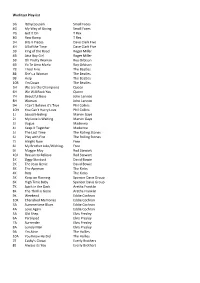

Wurlitzer Play-List 3G Itchycoo Park Small Faces 4G My Way of Giving Small Faces 7G Get It on T Rex 8G Raw Ramp T Rex 3H Bits N

Wurlitzer Play-list 3G Itchycoo park Small Faces 4G My Way of Giving Small Faces 7G Get It On T Rex 8G Raw Ramp T Rex 3H Bits n Pieces Dave Clark Five 4H All of the Time Dave Clark Five 3B King of the Road Roger Miller 4B Atta Boy Girl Roger Miller 5B Oh Pretty Woman Roy Orbison 6B Yo Te Amo Maria Roy Orbison 7B I Feel Fine The Beatles 8B She’s a Woman The Beatles 9B Help The Beatles 10B I’m Down The Beatles 5H We are the Champions Queen 6H We Will Rock You Queen 7H Beautiful Boys John Lennon 8H Woman John Lennon 9H I Can’t Believe it’s True Phil Collins 10H You Can’t Hurry Love Phil Collins 1J Sexual Healing Marvin Gaye 2J My Love is Waiting Marvin Gaye 3J Vogue Madonna 4J Keep it Together Madonna 5J The Last Time The Rolling Stones 6J Play with Fire The Rolling Stones 7J Alright Now Free 8J My Brother Jake/Wishing.. Free 9J Maggie May Rod Stewart 10J Reason to Believe Rod Stewart 1K Ziggy Stardust David Bowie 2K The Jean Genie David Bowie 3K The Apeman The Kinks 4K Rats The Kinks 5K Keep on Running Spencer Davis Group 6K High Time Baby Spencer Davis Group 7K Spirit in the Dark Aretha Franklin 8K The Thrill is Gone Aretha Franklin 9K Weekend Eddie Cochran 10K Cherished Memories Eddie Cochran 3A Summertime Blues Eddie Cochran 4A Love Again Eddie Cochran 5A Old Shep Elvis Presley 6A Paralysed Elvis Presley 7A Surrender Elvis Presley 8A Lonely Man Elvis Presley 9A I’m Alive The Hollies 10A You Know He Did The Hollies 7E Cathy’s Clown Everly Brothers 8E Always its You Everly Brothers . -

Diversity of K-Pop: a Focus on Race, Language, and Musical Genre

DIVERSITY OF K-POP: A FOCUS ON RACE, LANGUAGE, AND MUSICAL GENRE Wonseok Lee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Kristen Rudisill © 2018 Wonseok Lee All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Since the end of the 1990s, Korean popular culture, known as Hallyu, has spread to the world. As the most significant part of Hallyu, Korean popular music, K-pop, captivates global audiences. From a typical K-pop artist, Psy, to a recent sensation of global popular music, BTS, K-pop enthusiasts all around the world prove that K-pop is an ongoing global cultural flow. Despite the fact that the term K-pop explicitly indicates a certain ethnicity and language, as K- pop expanded and became influential to the world, it developed distinct features that did not exist in it before. This thesis examines these distinct features of K-pop focusing on race, language, and musical genre: it reveals how K-pop groups today consist of non-Korean musicians, what makes K-pop groups consisting of all Korean musicians sing in non-Korean languages, what kind of diverse musical genres exists in the K-pop field with two case studies, and what these features mean in terms of the discourse of K-pop today. By looking at the diversity of K-pop, I emphasize that K-pop is not merely a dance- oriented musical genre sung by Koreans in the Korean language. -

Page 1 of 163 Music

Music Psychedelic Navigator 1 Acid Mother Guru Guru 1.Stonerrock Socks (10:49) 2.Bayangobi (20:24) 3.For Bunka-San (2:18) 4.Psychedelic Navigator (19:49) 5.Bo Diddley (8:41) IAO Chant from the Cosmic Inferno 2 Acid Mothers Temple 1.IAO Chant From The Cosmic Inferno (51:24) Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo 3 Acid Mothers Temple 1.Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo (1:05:15) Absolutely Freak Out (Zap Your Mind!) 4 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.Star Child vs Third Bad Stone (3:49) 2.Supernal Infinite Space - Waikiki Easy Meat (19:09) 3.Grapefruit March - Virgin UFO – Let's Have A Ball - Pagan Nova (20:19) 4.Stone Stoner (16:32) 1.The Incipient Light Of The Echoes (12:15) 2.Magic Aum Rock - Mercurical Megatronic Meninx (7:39) 3.Children Of The Drab - Surfin' Paris Texas - Virgin UFO Feedback (24:35) 4.The Kiss That Took A Trip - Magic Aum Rock Again - Love Is Overborne - Fly High (19:25) Electric Heavyland 5 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.Atomic Rotary Grinding God (15:43) 2.Loved And Confused (17:02) 3.Phantom Of Galactic Magnum (18:58) In C 6 Acid Mothers Temple & The Melting Paraiso U.F.O. 1.In C (20:32) 2.In E (16:31) 3.In D (19:47) Page 1 of 163 Music Last Chance Disco 7 Acoustic Ladyland 1.Iggy (1:56) 9.Thing (2:39) 2.Om Konz (5:50) 10.Of You (4:39) 3.Deckchair (4:06) 11.Nico (4:42) 4.Remember (5:45) 5.Perfect Bitch (1:58) 6.Ludwig Van Ramone (4:38) 7.High Heel Blues (2:02) 8.Trial And Error (4:47) Last 8 Agitation Free 1.Soundpool (5:54) 2.Laila II (16:58) 3.Looping IV (22:43) Malesch 9 Agitation Free 1.You Play For -

Marvin Gaye Collected Mp3, Flac, Wma

Marvin Gaye Collected mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: Collected Country: UK Released: 2014 Style: Soul, Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1834 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1790 mb WMA version RAR size: 1648 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 360 Other Formats: MP3 WAV VQF DTS AHX DMF AU Tracklist 1-1 –Marvin Gaye (I'm Afraid) The Masquerade Is Over 1-2 –Marvin Gaye Let Your Conscience Be Your Guide 1-3 –Marvin Gaye Stubborn Kind Of Fellow 1-4 –Marvin Gaye Hitch Hike 1-5 –Marvin Gaye Pride And Joy 1-6 –Marvin Gaye Can I Get A Witness 1-7 –Marvin Gaye When I'm Alone I Cry 1-8 –Marvin Gaye You're A Wonderful One 1-9 –Marvin Gaye Try It Baby 1-10 –Marvin Gaye Baby Don't You Do It 1-11 –Marvin Gaye How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You) 1-12 –Marvin Gaye I'll Be Doggone 1-13 –Marvin Gaye Pretty Little Baby 1-14 –Marvin Gaye Ain't That Peculiar 1-15 –Marvin Gaye One More Heartache 1-16 –Marvin Gaye Little Darling (I Need You) 1-17 –Marvin Gaye Your Unchanging Love 1-18 –Marvin Gaye Chained 1-19 –Marvin Gaye I Heard It Through The Grapevine 1-20 –Marvin Gaye You 1-21 –Marvin Gaye Too Busy Thinking About My Baby 1-22 –Marvin Gaye The End Of Our Road 1-23 –Marvin Gaye That's The Way Love Is 2-1 –Marvin Gaye Abraham, Martin & John 2-2 –Marvin Gaye What's Going On 2-3 –Marvin Gaye Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology) 2-4 –Marvin Gaye Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler) 2-5 –Marvin Gaye Trouble Man 2-6 –Marvin Gaye Let's Get It On 2-7 –Marvin Gaye Come Get To This 2-8 –Marvin Gaye Distant Lover 2-9 –Marvin Gaye I Want You 2-10 –Marvin Gaye -

Free Marvin Gaye Songs

Free marvin gaye songs listen free to Marvin Gaye: Ain't No Mountain High Enough, What's Going On "I Heard It Through the Grapevine", "Let's Get It On" and "What's Going On". Listen to Marvin Gaye | SoundCloud is an audio platform that lets you listen to what you love and share Marvin Gaye - Let's Get It On (Ambassadeurs Remix). Here's the Marvin Gaye installment in the Free Soul series, released by Motown in Japan in While you'd have to make an effort to pick 21 tracks from. Listen to Marvin Gaye Radio, free! Stream songs by Marvin Gaye & similar artists plus get the latest info on Marvin Gaye! 5. Let's Get It On. View all on Spotify. One of the most gifted, visionary, and enduring talents ever launched into orbit by the Motown hit machine, Marvin. Many MARVIN GAYE song that you can listen to install the ''Ain't no Mountain High Enough'', Marvin Gaye - Sexual Healing, Marvin Gaye Marvin Gaye - What's Going On, Marvin Gaye - Inner City Blues, GOT TO. Marvin Gaye - Pandora. have things back to normal soon. Keep enjoying Pandora for free. Sign up for a free Pandora account now to keep the music playing. Would Marvin Gaye have maintained his status as one of the preeminent voices in soul music even amid the rising tide of hip-hop and harder. Many MARVIN GAYE song that you can listen to here. free install the application, select the song you like and play. This app only provides Mp3. Marvin Gaye All Music best application for android! Read more. -

Book 3 – Death and Other Possibilities – the Poetry of Allison

Death and other Possibilities Allison Grayhurst Edge Unlimited Publishing 2 Death and other Possibilities Copyright © 2000 by Allison Grayhurst First addition All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage, retrieval and transmission systems now known or to be invented without permission in writing from the author, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Cover Art (sculpture): “Possibilities” © 2012 by Allison Grayhurst Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Grayhurst, Allison, 1966- Death and other Possibilities “Edge Unlimited Publishing” Poems. ISBN-13: 978-1478208167 ISBN-10: 1478208163 Death and other Possibilities by Allison Grayhurst Title ID: 3931607 3 Table of Contents Sheaves of Time 7 Between Two Places 8 Change 9 In Time 10 Within This Hour 11 Falling 12 Replenished 13 The Voice That Calls To Me 14 You Were There 15 In The Tomb 16 Without Light 17 To Lie With Luck Again 18 Dark Wave 19 The Ghosts Around My Bed 20 Home 21 My Love is Waiting 22 Without Covers 23 The Gift 24 Through the thick middle 25 A Day For My Own 26 Whole 27 Morning 28 Things I Must Learn 29 New Commitment 30 Spiral 31 Dad (an eulogy) 32 In the Gully of Things 44 Open 45 Friendship 46 Like a harmonica 47 4 Pregnant After a Death 48 Imagination 49 Bright 50 Transfigured 51 In My Bones 52 My Place 53 I Found You Singing 54 Recovered 55 Silence 56 Like A Wave 57 In This Garden 58 before 59 The Gentle -

SONGS-SCOUT-SING.Pdf

Songs Scouts Sing (First E-Book Edition) Songs play an important part in Scouting. This book, with its hundreds of songs that Scouts love to sing, is a handy reference for all Scouts and Scout Leaders in the Philippines. This e-book edition of Songs Scouts Sing was created by Bong Saculles for the Boy Scouts of the Philippines. Cover design by Derek Bonifacio. Copyright © 2012 Boy Scouts of the Philippines All Rights Reserved. No part of this e-book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the Boy Scouts of the Philippines. Foreword Songs play an important part in Scouting. Through songs, the leader can set the mood and the emotional tone for any gathering, be it for solemn or joyous occasions or any other atmosphere in between. As a medium for emotional expression, the leader can use songs to fit the mood of a group or the other way around – influence the mood of a group through an appropriate song. Both, probably are true. And singing should be recognized by leaders as a force that can be used in the field of character-influencing, especially among Scouts. Scouts sing not only songs for fun, for there are many fun songs to sing songs in Scouting, but songs that fit and are appropriate for other Scouting occasions. We sing songs of fellowship because we enjoy each other’s company and friendship; we sing songs to commemorate events or express religious and patriotic fervor; we sing songs for greetings, farewell and inspiration, and through the singing, the wise leader can help his Scouts find a world of beauty and inspiration. -

Issues!!!) That Is Carried in Shops, As We Face Into 2012, Let Us Remember the Etc

December 2011 ::: Nollaig 2011 Artwork by Luana Stebulė Anthony Sullivan (Ireland) , L. Summerton Morgan (USA), Tomás Ó Cárthaigh (Ireland), Spiros Kitsinelis (Greece / France), Hal O Leary (USA), Matthew Walz (USA), Tatjana Debeljacki (Serbia), Lizzie Corsi (USA) Bernard Lorimer (Northern Ireland), Randall Aittaniemi (USA), Sabahudin Hadžialic (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Deepak Chaswal (India), Erica (USA). Kathy Coman (USA), Kim Wilson (USA), Gonzalo Salesky (Agentina), Rishan Singh (South Africa), Luiza Flynn-Goodlett (USA), Irena Jovanovic (Serbia),Dan Castle (USA), Greg Gunn (Canada), Lisa McCraw, (USA), Matthew Bell (Australia), Laura Cleary (Ireland), Niall O Conner (Ireland) Evin Okçuoglu (Turkey), Simon Rhee (USA), Elizabeth A. Fontaine (USA), Luana Stebule (Lithuania), Barbara Wühr (Germany / France), Frank C. Praeger (USA) Cartys Poetry Journal www.cartyspoetryjournal.com Activism and the Poet Foreword Activism is on the rise, look around, no As 2011 draws to a close, we have again mistake can be made about it. No more are another great year on which to look back, people standing on the sidelines, they are where we brought the best of poetry from getting out there to make their voices heard. Ireland and around the world to a readership What effect that they are having is totally in Ireland and around the world. another story, but they are getting out there anyway. We have seen and partaken in the 100,000 Poets for Change event, and look forward to From the Occupy! Movement – the Irish partaking in the 2012 event, we will be activism which is largely ignored here in the charting the participation in the 10 Years and local press – to the 100,000 Poets for Change Counting Project, we have seen the launch of event, started on Facebook by Michael the book locally by Ken Hume in Tullamore Rothenberg, to the 10 Years and Counting “Snowstorm of Doubt and Grace”, and event against the wars in the middle east and reported on the poetic events around Ireland.