Study of Major Aromatic Compounds in Port Wines from Carotenoid Degradation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synthesis of Allenic Ketones and the Role of Yeast in Their Conversion to Damascenone

SYNTHESIS OF ALLENIC KETONES AND THE ROLE OF YEAST IN THEIR CONVERSION TO DAMASCENONE Natoiya Dee Rayette Lloyd A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Adelaide School of Agriculture, Food and Wine Faculty of Science October 2013 Dedication This Thesis is dedicated to my dad, Robert Lloyd who passed away (03/10/1941 – 16/11/2009) and my wonderful mom, Maxine and brother, Ryan who are always there to support me. I am so grateful to have both of you in my life. i Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... i Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ iv Declaration ................................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... vii Publications .................................................................................................................................. ix Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................ x List of Figures, Schemes and Tables ............................................................................................. xi CHAPTER 1 Introduction .................................................................................................. -

Attenuated UV Radiation Alters Volatile Profile in Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes Under Field Conditions

Molecules 2015, 20, 16946-16969; doi:10.3390/molecules200916946 OPEN ACCESS molecules ISSN 1420-3049 www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules Article Attenuated UV Radiation Alters Volatile Profile in Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes under Field Conditions Di Liu 1, Yuan Gao 1, Xiao-Xi Li 1, Zheng Li 2 and Qiu-Hong Pan 1,* 1 Center for Viticulture & Enology, College of Food Science & Nutritional Engineering, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100083, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.L.); [email protected] (Y.G.); [email protected] (X.-X.L.) 2 Food Science and Human Nutrition Department, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-6273-6191; Fax: +86-6273-8658. Academic Editors: Susan E. Ebeler and Helene Hopfer Received: 30 July 2015 / Accepted: 9 September 2015 / Published: 17 September 2015 Abstract: This study aimed to explore the effect of attenuated UV radiation around grape clusters on the volatile profile of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes (Vitis vinifera L. cv.) under field conditions. Grape bunches were wrapped with two types of polyester films that cut off 89% (film A) and 99% (film B) invisible sunlight of less than 380 nm wavelength, respectively. Solar UV radiation reaching the grape berry surface was largely attenuated, and an increase in the concentrations of amino acid-derived benzenoid volatiles and fatty acid-derived esters was observed in the ripening grapes. Meanwhile, the attenuated UV radiation significantly reduced the concentrations of fatty acid-derived aldehydes and alcohols and isoprenoid-derived norisoprenoids. -

Developing 'Superyellow' Enhanced Pigment Sweet-Corn for Eye Health

Final Report Developing ‘superyellow’ enhanced pigment sweetcorn for eye-health. Dr Tim O'Hare The Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) Project Number: VG07081 VG07081 This project has been funded by Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited with co-investment from The Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF) and funds from the Australian Government. Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited (Hort Innovation) makes no representations and expressly disclaims all warranties (to the extent permitted by law) about the accuracy, completeness, or currency of information in Developing ‘superyellow’ enhanced pigment sweetcorn for eye-health.. Reliance on any information provided by Hort Innovation is entirely at your own risk. Hort Innovation is not responsible for, and will not be liable for, any loss, damage, claim, expense, cost (including legal costs) or other liability arising in any way (including from Hort Innovation or any other person’s negligence or otherwise) from your use or non-use of Developing ‘superyellow’ enhanced pigment sweetcorn for eye-health., or from reliance on information contained in the material or that Hort Innovation provides to you by any other means. ISBN 0 7341 3586 6 Published and distributed by: Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited Level 8, 1 Chifley Square Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: (02) 8295 2300 Fax: (02) 8295 2399 Developing 'Superyellow' enhanced pigment sweet-corn for eye health Project Leader: Dr Tim O’Hare (QAAFI, an alliance between DAF and the University of Queensland) Project Team: Dr -

Research Advances on Biosynthesis, Regulation, and Biological Activities of Apocarotenoid Aroma in Horticultural Plants

Hindawi Journal of Chemistry Volume 2020, Article ID 2526956, 11 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2526956 Review Article Research Advances on Biosynthesis, Regulation, and Biological Activities of Apocarotenoid Aroma in Horticultural Plants Jianan Shi,1 Chao Cao,1 Jiayu Xu,1 and Chunhua Zhou 1,2,3 1College of Horticulture and Plant Protection, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225009, China 2Institute of Agricultural Science and Technology Development, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225009, China 3Joint International Research Laboratory of Agriculture & Agri-Product Safety of Ministry of Education of China, Yangzhou University, Yangzhouv, China Correspondence should be addressed to Chunhua Zhou; [email protected] Received 1 March 2020; Accepted 3 April 2020; Published 4 May 2020 Guest Editor: Yunus Alparslan Copyright © 2020 Jianan Shi et al. 'is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Apocarotenoids, which play important roles in the growth and development of horticultural plants, are produced by the action of carotenoid cleavage oxygenase (CCO) family members or nonenzymatic cleavage actions. Apocarotenoids are commonly found in leaves, flowers, and fruits of many horticultural plants and participate in the formation of pigments, flavors, hormones, and signaling compounds. Some of them are recognized as important aroma components of fruit and flower with aromatic odor, such as βß-ionone, β-damascenone, and 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one in tomato fruit, and have low odor thresholds with β-ionone having odor threshold of only 0.007 ppb. In this review, the main apocarotenoid aroma components in horticultural plants were listed, and factors influencing their production were discussed at first. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

DEVELOPING HIGH FLAVOR QUALITY PROCESSED TOMATO PRODUCTS By YAOZHOU ZHU A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Yaozhou Zhu To my family and faculty advisors for their constant support and encouragement, especially my late grandfathers, who taught me how good fresh garden fruits and vegetables can taste ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my utmost gratitude to my committee chair, Dr. Paul J. Sarnoski for the tremendous amount of time he has given me throughout this research and his invaluable assistance with all the difficulties I have encountered along the way. I would like to thank Dr. Charles Sims, Dr. Lisa House, Dr. Maurice Marshall and Dr. Harry Klee for spending precious time to help me build my career and providing useful suggestions about my research whenever I needed it. Your guidance and advice will stay with me for many years to come. I also appreciate the support I received from Dr. Renee Goodrich-Schneider, Dr. Keith Schneider and Dr. George Baker, whose office doors were always open for me. The faculty members in the Food Science and Human Nutrition Department at UF have also played a crucial role in my academic career. I am particularly thankful to Dr. Asli Odabasi Kirli, Dr. Harry Sitren, Dr. Susan Percival, Dr. Jesse Gregory, Dr. Anita Wright, Dr. Liwei Gu and Dr. Michelle Danyluk. I would like to acknowledge Dr. Denise Tieman, Ms. Sara Marshall, Ms. Bridget Stokes, Dr. Yavuz Yagiz, and Ms. -

From Carotenoids to Norisoprenoids Summary

The chemistry and biogenesis of the C13-norisoprenoids in wine Marco LI CALZI, PhD ENOLFACTIVE, France Associate Professor of Enology Ecole d’Ingénieurs de PURPAN Toulouse, France [email protected] Summary • General presentation of C13-norisoprenoids: from carotenoids to norisoprenoids Summary • General presentation of C13-norisoprenoids: from carotenoids to norisoprenoids • Biosynthesis of the main C13-norisoprenoids Summary • General presentation of C13-norisoprenoids: from carotenoids to norisoprenoids • Biosynthesis of the main C13-norisoprenoids • Sensory impact of the main C13-norisoprenoids on wine General presentation of C13-norisoprenoids: from carotenoids to norisoprenoids Carotenoids Carotenoids are a family of 40-carbon yellow or orange photosynthetic pigments. Capable of absorbing light, they have a photoprotective role (Baumes et al., 2002). The plant is able to protect its photosynthetic sites from excessive light radiation (FÉRET, 2009) In Vitis vinifera species, carotenoids are present in the leaves and in the grape skins (Baumes et al., 2002), predominantly (85% of total carotenoids) present as β-carotene and lutein β-carotene General presentation of C13-norisoprenoids: from carotenoids to norisoprenoids Carotenoids Carotenoids are a family of 40-carbon yellow or orange photosynthetic pigments. Capable of absorbing light, they have a photoprotective role (Baumes et al., 2002). The plant is able to protect its photosynthetic sites from excessive light radiation (FÉRET, 2009) In Vitis vinifera species, carotenoids are present in the leaves and in the grape skins (Baumes et al., 2002), predominantly (85% of total carotenoids) present as β-carotene and lutein β-carotene Neoxanthin, violaxanthine, zeaxanthine, lutein-5,6-epoxide, neochrome (Baumes et al., 2002; Mendes Pinto, 2009). -

Β-Damascenone Precursors in Grapes and Wines

I .qt p-Damascenone Precursors in Grapes and Wines A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor Of Philosophy by George Kyriakos Skouroumounis (8. SC. Hons.) Department of Organic Chemistry The University of Adelaide 1 991 As no better man advances to take this matter in hand, I promise nothing complete; because any human thing supposed to be complete must for that very reason infallibly be faulty. (from Moby Dick, HeaMAN MELVTLLE) Contents Acknowledgements I Statement ii Publications iii Abstract iv Abbreviations vii Chapter 1: lntroduction 1 1.1 Norisoprenoids as Grape Components. 6 1.2 p-Damascenone (38). 13 1.3 Precursors of p-Damascenone (38) 15 Chapter 2: Preparation of Aglycones For Hydrolytic Studies. 24 2.1 Synthesis of (3S',5S',6R',9R' )' -7-megastigmyne- 3,6,9-triol (55a) 24 2.2 Synthesis of (3S', 9R)-5-Megastigmen-7-yne-3,9-diol (SBa) 46 2.3 Synthesis of Allenes, 6,7-Megastigmadiene-3,5,9-triol (43) 55 2.4 Synthesis of Model Enyne Alcohol (99) æ 2.5 Synthesis of Model Alcohol 3,5,5-Trimethyl-3-cyclohexen-1-ol (107). 60 2.6 Synthesis of 3-Hydroxy-p-damascone (39). 61 Chapter 3 3.1 lntroduction to p-Glycosidation Methods. 62 3.1.1 Heterogeneous Systems. 62 3.1.2 Homogeneous Systems 69 3.2 Synthesis of Geranyl-p-D-glucopyranoside (1a) 81 3.3 Synthesis of 4-Oxo-5-megastigmen-9-yl- tetra-O-acetyl-p-D-glucopyranoside (153). 84 3.4 Synthesis of 3,5,S-Trimethyl-3-cyclohexenyl-p-D- glucopyranoside (1 07a). -

The Application of Ozonated Water Rearranges the Vitis Vinifera L. Leaf and Berry Transcriptomes Eliciting Defence and Antioxida

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The application of ozonated water rearranges the Vitis vinifera L. leaf and berry transcriptomes eliciting defence and antioxidant responses Ana Campayo1,2,5, Stefania Savoi3,5, Charles Romieu3, Alberto José López‑Jiménez4, Kortes Serrano de la Hoz2, M. Rosario Salinas1, Laurent Torregrosa3* & Gonzalo L. Alonso1 Ozonated water has become an innovative, environmentally friendly tool for controlling the development of fungal diseases in the vineyard or during grape postharvest conservation. However, little information is currently available on the efects of ozonated water sprayings on the grapevine physiology and metabolism. Using the microvine model, we studied the transcriptomic response of leaf and fruit organs to this treatment. The response to ozone was observed to be organ and developmental stage‑dependent, with a decrease of the number of DEGs (diferentially expressed genes) in the fruit from the onset of ripening to later stages. The most highly up‑regulated gene families were heat‑shock proteins and chaperones. Other up‑regulated genes were involved in oxidative stress homeostasis such as those of the ascorbate–glutathione cycle and glutathione S‑transferases. In contrast, genes related to cell wall development and secondary metabolites (carotenoids, terpenoids, phenylpropanoids / favonoids) were generally down‑regulated after ozone treatment, mainly in the early stage of fruit ripening. This down‑regulation may indicate a possible carbon competition favouring the re‑establishment and maintenance of the redox homeostasis rather than the synthesis of secondary metabolites at the beginning of ripening, the most ozone responsive developmental stage. Vitis vinifera encompasses most grapevine cultivars used for table grape and wine production. -

Carotenoids As Flavor & Fragrance Precursors , Leffingwell Reports

Leffingwell Reports, Vol. 2 (No. 3), October, 2002 1 Carotenoids as Flavor & Fragrance Precursors A Review by John C. Leffingwell. Ph.D. This is the introduction to our series on aroma materials produced by carotenoid degradation. Carotenoids are the pigments responsible for the colors of many plants, fruits and flowers. They serve as Light Harvesting Complexes (with proteins) in photosynthesis. Carotenoids are important in human nutrition as a source of Vitamin A (e.g., from beta-carotene) and as a prevention agent for cancer and heart disease (e.g. lycopene). In addition, carotenoids add color to foods and beverages (e.g. orange juice). And in addition, carotenoids are the precursors of many important chemicals responsible for the flavor of foods and the fragrance of flowers. Carotenoids are a class of hydrocarbons (carotenes) and their oxygenated derivatives (xanthophylls). About 600 carotenoids have been isolated from natural sources. Where are Carotenoids Found in Nature For us, the most important source for carotenoids are plants, where often the brilliant colors of the carotenoids are masked by the green chlorophyllic pigments (i.e. in green vegetables and leaves). In a number of cases, as plants mature, the chlorophyll content decreases leaving the carotenoids responsible for the beautiful colors of most fruits (pineapple, oranges, lemons, grapefruit, strawberry, tomatoes, paprika, rose hips) and many flowers (Eschscholtzia, Narcissus). Carotenoids are also responsible for the colors of some birds (flamingo, canary), certain insects, and marine animals (shrimp, lobster and salmon). Health Aspects of Carotenoids Carotenoids are important factors in human health and essential for vision. The role of beta-carotene and other carotenoids as the main dietary source of vitamin A has been known for the better part of this century. -

Environmental and Seasonal Influences on Red Raspberry Flavour

Theor Appl Genet DOI 10.1007/s00122-012-1957-9 ORIGINAL PAPER Environmental and seasonal influences on red raspberry flavour volatiles and identification of quantitative trait loci (QTL) and candidate genes Alistair Paterson • Angzzas Kassim • Susan McCallum • Mary Woodhead • Kay Smith • Dzeti Zait • Julie Graham Received: 18 May 2012 / Accepted: 27 July 2012 Ó Springer-Verlag 2012 Abstract Raspberry volatiles are important for percep- Introduction tions of sensory quality, mould resistance and some have nutraceutical activities. Twelve raspberry character vola- Flavour character in fruit originates through interactions tiles were quantified, 11 of them in fruit from two seasons, between sugars, organic acids and a subset of approxi- from plants from the Glen Moy 9 Latham mapping pop- mately 200 volatile compounds (Klesk et al. 2004). Rasp- ulation growing in both open field and under cover (poly- berry fruit produce an array of volatile compounds tunnels). Effects of season and environment were examined (Robertson et al. 1995; Aprea et al. 2010) with content for their impact on the content of a-ionone, a-ionol, showing significant variations influenced by genotype, b-ionone, b-damascenone, linalool, geraniol, benzyl alco- environment and season which impacts on flavour (Moore hol, (Z)-3-hexenol, acetoin, acetic and hexanoic acids, and Burrows 2002; Du and Qian 2010). Of the 230 vola- whilst raspberry ketone was measured in one season. A tiles characterised in raspberry, only 12 have been identi- significant variation was observed in fruit volatiles in all fied as of character impact (Jiang 1991; Larsen et al. 1991): progeny between seasons and method of cultivation. -

Light-Controlled Fruit Pigmentation and Flavor Volatiles in Tomato and Bell Pepper

antioxidants Article Light-Controlled Fruit Pigmentation and Flavor Volatiles in Tomato and Bell Pepper Hee Ju Yoo 1, Jin-Hyun Kim 2, Kyoung-Sub Park 2,3, Jung Eek Son 4 and Je Min Lee 1,* 1 Department of Horticultural Science, Kyungpook National University, Daegu 41566, Korea; [email protected] or [email protected] 2 Protected Horticulture Research Institute, National Institute of Horticultural & Herbal Science, RDA, Haman 52054, Korea; [email protected] (J.-H.K.); [email protected] (K.-S.P.) 3 Department of Horticultural Science, Mokpo National University, Muan 58554, Korea 4 Department of Plant Science, Seoul National University Seoul, Seoul 08826, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 November 2019; Accepted: 19 December 2019; Published: 23 December 2019 Abstract: Light is a major environmental factor affecting the regulation of secondary metabolites, such as pigments and flavor. The Solanaceae plant family has diverse patterns of fruit metabolisms that serve as suitable models to understand the molecular basis of its regulation across species. To investigate light-dependent regulation for fruit pigmentation and volatile flavors, major fruit pigments, their biosynthetic gene expression, and volatiles were analyzed in covered fruits of tomato and bell pepper. Immature covered fruits were found to be ivory in color and no chlorophyll was detected in both plants. The total carotenoid content was found to be reduced in ripe tomato and bell pepper under cover. Naringenin chalcone decreased more than 7-fold in ripe tomato and total flavonoids decreased about 10-fold in immature and ripe pepper fruit under light deficiency. -

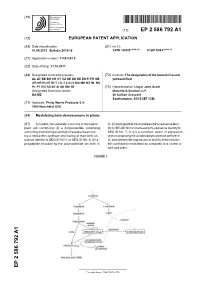

Modulating Beta-Damascenone in Plants

(19) TZZ 58679 _T (11) EP 2 586 792 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 01.05.2013 Bulletin 2013/18 C07K 14/415 (2006.01) C12N 15/82 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 11187332.9 (22) Date of filing: 31.10.2011 (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventor: The designation of the inventor has not AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB yet been filed GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR (74) Representative: Lloyd, John Scott Designated Extension States: Maschio & Soames LLP BA ME 20 Carlton Crescent Southampton, SO15 2ET (GB) (71) Applicant: Philip Morris Products S.A. 2000 Neuchâtel (CH) (54) Modulating beta-damascenone in plants (57) A mutant, non-naturally occurring or transgenic (i); (iii) a polypeptide having at least 66% sequence iden- plant cell comprising: (i) a polynucleotide comprising, tity to SEQ ID NO: 2 or at least 60% sequence identity to consisting or consisting essentially of a sequence encod- SEQ ID No. 7; or (iv) a construct, vector or expression ing a neoxanthin synthase and having at least 60% se- vector comprising the isolated polynucleotide set forth in quence identity to SEQ ID NO:1 or SEQ ID No. 6; (ii) a (i), and wherein the expression or activity of the neoxan- polypeptide encoded by the polynucleotide set forth in thin synthase is modulated as compared to a control or wild type plant. EP 2 586 792 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 2 586 792 A1 Description FIELD OF THE INVENTION 5 [0001] The present invention discloses the polynucleotide sequences of neoxanthin synthase, lycopene beta cyclase and 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase from Nicotiana tabacum and variants, homologues and fragments thereof.