Digibooklet Paul Tortelier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

And Nineteenth-Century Viola Da Gamba and Violoncello Performance Practices Sarah Becker Trinity University, [email protected]

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Music Honors Theses Music Department 4-19-2013 Sexual Sonorities: Gender Implications in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Viola da Gamba and Violoncello Performance Practices Sarah Becker Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/music_honors Recommended Citation Becker, Sarah, "Sexual Sonorities: Gender Implications in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Viola da Gamba and Violoncello Performance Practices" (2013). Music Honors Theses. 6. http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/music_honors/6 This Thesis open access is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sexual Sonorities: Gender Implications in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Viola da Gamba and Violoncello Performance Practices Sarah Becker A DEPARTMENT HONORS THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF_________MUSIC______________AT TRINITY UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR GRADUATION WITH DEPARTMENTAL HONORS DATE 04/19/2013 ______ ____________________________ ________________________________ THESIS ADVISOR DEPARTMENT CHAIR __________________________________________________ ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT FOR ACADEMIC AFFAIRS, CURRICULUM AND STUDENT ISSUES Student Copyright Declaration: the author has selected the following copyright provision (select only one): [X] This thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which allows some noncommercial copying and distribution of the thesis, given proper attribution. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA. [ ] This thesis is protected under the provisions of U.S. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Critical Success Factors in Cello Training a Comparative Study

Critical success factors in cello training a comparative study by Anzél Gerber Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PhD Music (Performance Practice) in the Department of Music Goldsmiths College, University of London Supervisor Professor Alexander Ivashkin 2008 (ii) DECLARATION I, Anzél Gerber, the undersigned, hereby declare that this dissertation, submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree PhD Music (Performance Practice), is my own original work. Signed: _______________________ Anzél Gerber (iii) ABSTRACT The research focused on the identification and ranking of critical success factors that contribute most significantly towards the training of a cello student. The empirical study was based on a sample of cello teachers in four countries selected for the study, namely Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States of America. A literature study, identifying a broad category of factors that could contribute towards successful cello training, formed the basis of the questionnaire. These critical success factors included the quality of the teacher, acquired skills, the talent and giftedness of the student, support rendered to the student, and the curriculum. Each of these factors comprised five sub factors. The respondents were required to rank these factors in order of importance. In the final analysis, they were requested to rank the five main factors. A statistical process of ranking (forced ranking) and Kruskal-Wallis was applied to rank and analyse the responses of the cello teachers in the survey. The critical success factors that contribute the most significantly towards successful cello training were identified and compared. ________________________________ (iv) PREFACE This study is in partial fulfilment for the degree PhD Music Performance at Goldsmiths College, University of London. -

A Pedagogical Analysis of Dvorak's Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op

A Pedagogical Analysis of Dvorak’s Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 by Zhuojun Bian B.A., The Tianjin Normal University, 2006 M.Mus., University of Victoria, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Cello) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2017 © Zhuojun Bian, 2017 Abstract I first heard Antonin Dvorak’s Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 when I was 13 years old. It was a memorable experience for me, and I was struck by the melodies, the power, and the emotion in the work. As I became more familiar with the piece I came to understand that it holds a significant position in the cello repertory. It has been praised extensively by cellists, conductors, composers, and audiences, and is one of the most frequently performed cello concertos since it was premiered by the English cellist Leo Stern in London on March 19th, 1896, with Dvorak himself conducting the Philharmonic Society Orchestra. In this document I provide a pedagogical method as a practical guide for students and cello teachers who are planning on learning this concerto. Using a variety of historical sources, I provide a comprehensive understanding of some of the technical challenges presented by this work and I propose creative and effective methods for conquering these challenges. Most current studies of Dvorak’s concerto are devoted to the analysis of its structure, melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, instrumentation, and orchestration. Unlike those studies, this thesis investigates etudes and student concertos that were both precursors to – and contemporary with – Dvorak’s concerto. -

The Issue of Size: a Glimpse Into the History of the Violoncello Piccolo

Page 1 The Issue of Size: A Glimpse into the History of the Violoncello Piccolo by Johanna Randvere Early Music Department University of the Arts, Sibelius Academy April 2020 Page 2 Abstract The aim of this research is to find out whether, how and why the size, tuning and the number of strings of the cello in the 17th and 18th centuries varied. There are multiple reasons to believe that the instrument we now recognize as a cello has not always been as clearly defined as now. There are written theoretical sources, original survived instruments, iconographical sources and cello music that support the hypothesis that smaller-sized cellos – violoncelli piccoli – were commonly used among string players of Europe in the Baroque era. The musical examples in this paper are based on my own experience as a cellist and viol player. The research is historically informed (HIP) and theoretically based on treatises concerning instruments from the 17th and the 18th centuries as well as articles by colleagues around the world. In the first part of this paper I will concentrate on the history of the cello, possible reasons for its varying dimensions and how the size of the cello affects playing it. Because this article is quite cello-specific, I have included a chapter concerning technical vocabulary in order to make my text more understandable also for those who are not acquainted with string instruments. In applying these findings to the music written for the piccolo, the second part of the article focuses on the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, namely cantatas with obbligato piccolo part, Cello Suite No. -

The Search for Consistent Intonation: an Exploration and Guide for Violoncellists

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2017 THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS Daniel Hoppe University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.380 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hoppe, Daniel, "THE SEARCH FOR CONSISTENT INTONATION: AN EXPLORATION AND GUIDE FOR VIOLONCELLISTS" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 98. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/98 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Download Booklet

Charming Cello BEST LOVED GABRIEL SCHWABE © HNH International Ltd 8.578173 classical cello music Charming Cello the 20th century. His Sérénade espagnole decisive influence on Stravinsky, starting a Best loved classical cello music uses a harp and plucked strings in its substantial neo-Classical period in his writing. A timeless collection of cello music by some of the world’s greatest composers – orchestration, evoking Spain in what might including Beethoven, Haydn, Schubert, Vivaldi and others. have been a recollection of Glazunov’s visit 16 Goodall: And the Bridge is Love (excerpt) to that country in 1884. ‘And the Bridge is Love’ is a quotation from Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of 1 6 Johann Sebastian BACH (1685–1750) Franz Joseph HAYDN (1732–1809) 14 Ravel: Pièce en forme de habanera San Luis Rey which won the Pulitzer Prize Bach: Cello Suite No. 1 in G major, 2:29 Cello Concerto in C major, 9:03 (arr. P. Bazelaire) in 1928. It tells the story of the collapse BWV 1007 – I. Prelude Hob.VIIb:1 – I. Moderato Swiss by paternal ancestry and Basque in 1714 of ‘the finest bridge in all Peru’, Csaba Onczay (8.550677) Maria Kliegel • Cologne Chamber Orchestra through his mother, Maurice Ravel combined killing five people, and is a parable of the Helmut Müller-Brühl (8.555041) 2 Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835–1921) his two lineages in a synthesis that became struggle to find meaning in chance and in Le Carnaval des animaux – 3:07 7 Robert SCHUMANN (1810–1856) quintessentially French. His Habanera, inexplicable tragedy. -

A Guide for Playing the Viola Without a Shoulder Rest Chin Wei Chang University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 A Guide for Playing the Viola Without a Shoulder Rest Chin Wei Chang University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Chang, C.(2018). A Guide for Playing the Viola Without a Shoulder Rest. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5036 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Guide for Playing the Viola Without a Shoulder Rest by Chin Wei Chang Bachelor of Music National Sun Yat- sen University, 2010 Master of Music University of South Carolina, 2015 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: Daniel Sweaney, Major Professor Kunio Hara, Committee Member Craig Butterfield, Committee Member Ari Streisfeld, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Chin Wei Chang, 2018 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my dearest parents, San-Kuei Chang and Ching-Hua Lai. Thank you for all your support and love while I have pursued my degree over the past six years. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I truly appreciate the director of the dissertation, Dr. Daniel Sweaney, for his advice, inspiration, and continuous encouragement over the past four years. -

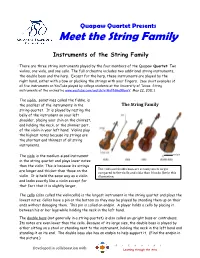

Meet the String Family

Quapaw Quartet Presents Meet the String Family Instruments of the String Family There are three string instruments played by the four members of the Quapaw Quartet: Two violins, one viola, and one cello. The full orchestra includes two additional string instruments, the double bass and the harp. Except for the harp, these instruments are played by the right hand, either with a bow or plucking the strings with your fingers. [See short examples of all five instruments on YouTube played by college students at the University of Texas: String instruments of the orchestra www.youtube.com/watch?v=RxFNHeXKmrY May 22, 2011.] The violin, sometimes called the fiddle, is the smallest of the instruments in the The String Family string quartet. It is played by resting the belly of the instrument on your left shoulder, placing your chin on the chinrest, and holding the neck, or the skinnier part, of the violin in your left hand. Violins play the highest notes because its strings are the shortest and thinnest of all string instruments. The viola is the medium-sized instrument endpin in the string quartet and plays lower notes than the violin. This is because its strings The cello and double bass are actually much larger are longer and thicker than those on the compared to the violin and viola than it looks like in this violin. It is held the same way as a violin illustration. and looks exactly like a violin except for that fact that it is slightly larger. The cello (also called the violincello) is the largest instrument in the string quartet and plays the lowest notes. -

Cello Solo Journey Albeniz · Brey · De Ziah · Diezig · Piazzolla · Prokofiev Rostropovich · Rozsa · Sollima · Taguell · Tcherepnine

95964 Cello Solo Journey Albeniz · Brey · De Ziah · Diezig · Piazzolla · Prokofiev Rostropovich · Rozsa · Sollima · Taguell · Tcherepnine Luciano Tarantino Cello Solo Journey The World is my cello A few years ago, the cellist Luciano Tarantino conceived ‘Cello Solo Journey’ as a Paul Tortelier 1914-1990 Giovanni Sollima b.1962 recital for concert performance. He gathered music from across Europe and America Suite Mon Cirque 15 Alone 4’33 with the aim of showing how the possibilities of writing for solo cello continue to 1 I. En Piste 0’41 develop and expand with the imagination of composers, as they find expressive 2 II. Poneys 3’07 Isaac Albéniz 1860-1909 regions of the instrument opened up, like new continents, through technical 3 III. L’Escamoteur 1’57 16 Asturia 7’07 innovation. 4 IV. Paillettes 2’44 In concert he opened his recital with the pioneers of solo cello music: not only 5 V. L’Hypnotiseur 1’55 Astor Piazzolla 1921-1992 the great Johann Sebastian but also cellist-composers of the 18th century such as 6 VI. Haute voltige 3’39 17 Tango Etude No.3 3’40 Evariste Felice dell’Abaco. With this album, however, Tarantino focused on the 7 VII. Dejà fini… 1’39 renaissance of the cello during the last century as an instrument sufficient unto itself, Rogerio y Taguell 1882-1956 not requiring support or accompaniment. Perhaps the signal event in this renaissance Sergei Prokofiev 1891-1953 18 Suite espagnole No.1 was the release in 1939 of the first-ever complete recording of Bach’s six cello suites 8 Sonata Op.134 7’48 – Flamenco 2’16 – the Old Testament of the repertoire, it could be said – by the Catalan cellist Pablo Casals.