Open PDF 279KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index Uploaded March 2019 (Download As PDF)

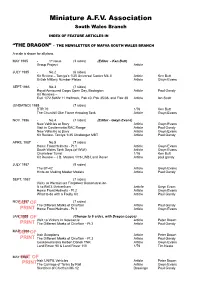

Miniature A.F.V. Association South Wales Branch INDEX OF FEATURE ARTICLES IN “THE DRAGON” - THE NEWSLETTER OF MAFVA SOUTH WALES BRANCH A scale is shown for all plans. MAY 1985 - 1st issue (3 sides) (Editor - Ken Butt) Group Project Article JULY 1985 - No.2 (6 sides) Kit Review – Tamiya’s 1/35 Universal Carrier Mk. II Article Ken Butt British Military Number Plates Article Gwyn Evans SEPT.1985 - No.3 (7 sides) Royal Armoured Corps Open Day, Bovington Article Paul Gandy Kit Reviews – Esci 1/72 SdKfz 11 Halftrack, Pak 40, Pak 35/36, and Flak 38 Article Ian Scott (UNDATED) 1985 (7 sides) BTR 70 1/76 Ken Butt The Churchill Oke Flame throwing Tank Article Gwyn Evans NOV. 1986 - No.4 (7 sides) (Editor - Gwyn Evans) New Vehicles at Bovy Article Gwyn Evans Visit to Castlemartin RAC Range Article Paul Gandy New Vehicles at Bovy Article Gwyn Evans Kit Review- Tamiya 1/35 Challenger MBT Article Paul Gandy APRIL 1987 - No.5 (7 sides) Home Front Helmets - Pt.1 Article Gwyn Evans South Wales Tank Days (of WWI) Article Gwyn Evans Charioteer Turret 1/76 Ken Butt Kit Review – J.B. Models 1/76 LWB Land Rover Article paul gandy JULY 1987 (8 sides) The BT-42 Article Gwyn Evans Hints on Making Master Models Article Paul Gandy SEPT. 1987 (7 sides) Visits to Warminster Firepower Demonstration & to RMCS Shrivenham Article Gwyn Evans Home Front Helmets - Pt.2 Article Gwyn Evans What to do with a Faulty Kit Article Paul Gandy NOV.OUT 1987 OF (7 sides) The Different Marks of Chieftain Article Paul Gandy PRINT Home Front Helmets - Pt.3 Article Gwyn Evans JAN.OUT -

Obsolescent and Outgunned: the British Army's Armoured Vehicle

House of Commons Defence Committee Obsolescent and outgunned: the British Army’s armoured vehicle capability Fifth Report of Session 2019–21 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 9 March 2021 HC 659 Published on 14 March 2021 by authority of the House of Commons The Defence Committee The Defence Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Ministry of Defence and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Tobias Ellwood MP (Conservative, Bournemouth East) (Chair) Stuart Anderson MP (Conservative, Wolverhampton South West) Sarah Atherton MP (Conservative, Wrexham) Martin Docherty-Hughes MP (Scottish National Party, West Dunbartonshire) Richard Drax MP (Conservative, South Dorset) Rt Hon Mr Mark Francois MP (Conservative, Rayleigh and Wickford) Rt Hon Kevan Jones MP (Labour, North Durham) Mrs Emma Lewell-Buck MP (Labour, South Shields) Gavin Robinson MP (Democratic Unionist Party, Belfast East) Rt Hon John Spellar MP (Labour, Warley) Derek Twigg MP (Labour, Halton) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright-parliament. Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at committees.parliament.uk/committee/24/defence-committee/ and in print by Order of the House. -

At Short Notice: UK AFV and PPV Procurement Using Uors 1

At Short Notice: UK AFV and PPV Procurement using UORs 1 Peter D. Antill, Jeremy C. D. Smith and David M. Moore Introduction During the recent conflicts in both Iraq and Afghanistan, the problems of providing protected mobility to troops on the ground, especially in view of the limited availability of Chinook helicopters, has received attention from the Media, from Coroners and in Parliament. The equipment in service at the time provided certain capabilities but were either fast and agile but lacked protection against mines and Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) or were much better protected, but slow and had relatively high operating costs. These included: • 'Snatch' Land Rovers – an up-armoured version of the Land Rover Defender 110, they were widely used in Northern Ireland and on peacekeeping missions where the threat environment was considered low. 2 Their use in Iraq and Afghanistan has been criticised because despite being armoured against small arms fire, the vehicles have proven susceptible to IEDs and over thirty-seven casualties have been attributed to the vehicle's lack of protection. 3 Such was the disillusionment, that armed forces personnel started calling it the 'mobile coffin'. 4 • Warrior – an infantry fighting vehicle (IFV) which grew out of the 1970s MCV-80 project. Some 789 vehicles were produced by GKN Defence, the Warrior entering service in 1987 with the 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards. Comparatively well armed and armoured (having a 30mm Rarden cannon and 7.62mm chain gun), these vehicles are now over twenty years old, with increasing maintenance costs and in need of upgrading. 5 • FV432 – replaced by the Warrior IFV, the FV432 was built by GKN Sankey up until 1971 when over 3,000 had been produced. -

Blast Analysis of Composite V-Shaped Hulls: an Experimental And

CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY DEFENCE COLLEGE OF MANAGEMENT AND TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE EngD THESIS Academic Year 2010-2011 STEPHANIE FOLLETT BLAST ANALYSIS OF COMPOSITE V-SHAPED HULLS: AN EXPERIMENTAL AND NUMERICAL APPROACH SUPERVISOR: DR AMER HAMEED July 2011 © Cranfield University 2011. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright owner. “THE LENGTH OF THIS DOCUMENT DEFENDS IT WELL AGAINST THE RISK OF ITS BEING READ” WINSTON CHURCHILL (30 NOVEMBER 1874 – 24 JANUARY 1965) [i] ABSTRACT During armed conflicts many casualties can be attributed to incidents involving vehicles and landmines. As a result mine protective features are now a pre-requisite on all armoured vehicles. Recent and current conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have shown that there is a requirement for vehicles that not only provide suitable protection against explosive devices but are also lightweight so that they may travel off-road and avoid the major routes where these devices are usually planted. This project aims to address the following two topics in relation to mine protected vehicles. 1. Could composite materials be used to replace conventional steels for the blast deflector plates located on the belly of the vehicle, and 2. How effective and realistic is numerical analysis in predicting the material response of these blast deflectors. It also looks into the acquisition and support of new equipment into the armed services, where the equipment itself is but one small element of the system involved. The first topic has been addressed by conducting a number of experimental tests using third scale V-shaped hulls manufactured from steel and two types of composite, S2 glass and E glass.