University of Kwazulu-Natal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

Compromised Sexual Territoriality Under Reflexive Cosmopolitanism: from Coffee Bean to Gay Bean in South Korea

한국지역지리학회지 제23권 제1호(2017) 23-46 Compromised Sexual Territoriality Under Reflexive Cosmopolitanism: From Coffee Bean to Gay Bean in South Korea Robert Hamilton* 이성애 중심 공간에서 조화로운 게잉과 게이의 성적 수행 공간으로: 종로구 ‘게이빈’ 사례를 중심으로 로버트 해밀튼* Abstract:This article examines the sexualization of place under conditions of the compressed modernization and reflexive cosmopolitanism. In particular, I adopt Michel de Certeau’s spatial didactic model of strategy and tactic to investigate the dynamics at play in the gay labelling of a Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf (Coffee Bean) in South Korea, and explore the ‘gaying’ that takes place within preconceived heteronormative space. Using interview data, I additionally explore the negotiation tactics and coping mechanisms at work when gays compete with heterosexuals for non-gay place. The results illustrate how gays gay in heteronormative space and how heteronormative space harmoniously embodies gay men. The findings suggest that spatial location and tactic play important roles in stimulating compromise of sexual territory. Gay Bean benefits from being nestled between locations with histories of tolerance, while it also prospers from reflexive cosmopolitan ideals of diversity and acceptance of others. Gay identity and gaying is interpreted as foreign in Korea, which buttresses gay performativity in spaces welcoming of foreigners and so-called “deviance.” However, how gaying functions within place relies not only on spatial histories of tolerance outside, but also on the tactics of identity negotiation within. The findings suggest that spatial and tactical conditions induce gay individuals to police other gay- identified individuals when gays gay in so-called heteronormative places. Key Words:Gay Bean, Gaying, Sexual Space, Territoriality, Reflexive Cosmopolitanism, Jong-no 요약:본 연구는 종로구에 위치한 커피빈이 어떻게 ‘게이빈’으로 불리며 게이들의 모임 장소라는 성적인 이미지가 생겼는지를 분석하는 것이다. -

Food, Tradition, Festivals and Culture

MODULE 4 – FOOD, TRADITION, FESTIVALS AND CULTURE South Korea is a country rich in culture and tradition. The lineage of the Korean tradition helped to shape up the modern South Korea. The country is a vivacious platform to showcase the rich heritage through festivals, dressing, food, lifestyle, arts and crafts etc. Various temples, fortresses, monuments etc. exhibit the tangible cultural heritage of South Korea and the festivals, performing arts, customs, lifestyle etc. exhibit the intangible cultural heritage of South Korea. Content Partner: DELICACIES 2 While on a vacation, every Indian Traveller wishes for a comprehensive experience involving sightseeing, stay, relaxation and most importantly food. South Korea is a gastronomical delight for Indian Travellers as the country’s delicacies are full of flavours and spices to tickle the taste buds of your guests. The recommended dishes that your guests can savour while on a vacation in South Korea are – Bibimbap, literally meaning mixed rice, is a combination Kimchi, a staple South Korean cuisine, is a traditional side of rice, meat and vegetables infused with spices and dish made from salted, fermented vegetables, most herbs giving it rich colours and aroma. For your commonly napa cabbage and South Korean radishes with a vegetarian guests, the dish can be customized to replace variety of seasonings including chilli meat with exotic vegetables. powder, scallions, garlic, ginger and salted seafood. There are hundreds of varieties of kimchi made with different vegetables as the main ingredients. Samgyetang or Ginseng Chicken Soup is a warm rich Bingsu, a South Korean dessert prepared with Red Bean flavoured soup where Ginseng herb is used paste as the base, adding crushed ice, ice cream and predominantly. -

Aubergine Written by JULIA CHO Directed by Flordelino Lagundino Study Guide

HISTORICAL CONTEXT ON STAGE AT PARK SQUARE THEATRE Oct 8-15, 2019 Cover Art: Richard Fleischman Aubergine Written by JULIA CHO Directed by Flordelino Lagundino Study Guide www.parksquaretheatre.org | page 1 HISTORICAL CONTEXT Aubergine Contributors Park Square Theatre Park Square Theatre Study Guide Staff Teacher Advisory Board EDITOR Marcia Aubineau Tanya Sponholz*, Prescott High School University of St. Thomas, retired COPY EDITOR Ben Carpenter Marcia Aubineau* MPLS Substitute Teacher Liz Erickson CONTRIBUTORS Rosemount High School, retired Tanya Sponholz*, Maggie Quam*, Theodore Fabel Alexandra Howes*, Ben Carpenter* South High School Amy Hewett-Olatunde COVER DESIGN AND LAYOUT Humboldt High School Connor M McEvoy (Education Sales and Cheryl Hornstein Services Manager) Freelance Theatre and Music Educator Alexandra Howes * Past or Present Member of the Park Square Theatre Teacher Advisory Board Twin Cities Academy Heather Klug Park Center High School Kristin Nelson Brooklyn Center High School Jennifer Parker Falcon Ridge Middle School Maggie Quam Contact Us Hmong College Prep Academy Kate Schilling PARK SQUARE THEATRE Mound Westonka High School 408 Saint Peter Street, Suite 110 Jack Schlukebier Saint Paul, MN 55102 Central High School, retired Education Sales: Connor M McEvoy EDUCATION: 651.291.9196 Sara Stein [email protected] Eden Prairie High School Tanya Sponholz Prescott High School If you have any questions or comments about Jill Tammen this guide or Park Square Theatre’s Education Hudson High School, retired Program, please contact Craig Zimanske Mary Finnerty, Director of Education Forest Lake Area High School PHONE 651.767.8494 EMAIL [email protected] www.parksquaretheatre.org | page 2 StudyHISTORICAL CONTEXTGuide Aubergine Study Guide Contents The Play Meet the Characters ........................................................................................................ -

P28-31 Layout 1

30 Established 1961 Wednesday, November 8, 2017 Lifestyle Features This undated handout photo provided by South Korea’s presidential Blue House in Seoul shows the meal to be served at the state dinner for US President Donald Trump and First Lady Melania Trump. — AFP photos burgers, accompanied by tomato ketchup, and the cen- terpiece of the state banquet there was a steak. The Seoul meal also features a prawn that Moon’s office said Sauce older than US on was caught near a disputed island claimed both by the South and Japan. The Seoul-controlled island off the east coast-called Dokdo in Korea and Takeshima in Japan-is at the heart of a decades-long territorial dispute between the two coun- Trump’s South Korea menu tries, both of them US allies who are confronted by the threat of nuclear-armed North Korea. And in another diplomatic jab at Tokyo, Moon’s office invited Lee Yong- special sauce more than a century older than the tens of thousands of dollars per liter. In one food show in Soo, a former wartime sex slave for Japanese soldiers, to United States will be on the menu for Donald 2012, a group of artisans displayed soy sauce they the state dinner. Trump at his state banquet in Seoul on Tuesday- claimed had been made 450 years ago, with a price tag A The plight of so-called “comfort women” is a hugely along with a diplomatically tricky prawn. The dinner, at of 100 million won ($90,000). Tuesday’s menu also emotional issue that has also marred ties between the presidential Blue House compound next to a former includes a grilled sole, known to be Trump’s favourite Seoul and Tokyo for decades. -

Epicure Academy Overview

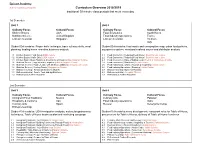

Epicure Academy a new culinary program Curriculum Overview 2018/2019 traditional 50 minute class periods that meet every day 1st Semester Unit 1 Unit 2 Culinary Focus Cultural Focus Culinary Focus Cultural Focus Kitchen Basics USA Food Economics South Korea Nutrition Science United Kingdom Food Industry Operations France Entrepreneurship Singapore Entrepreneurship Vietnam Italy Student Deliverables: Proper knife technique, basic culinary skills, meal Student Deliverables: food waste and consumption map, urban food policies, planning, healing home remedies,business analysis aquaponics system, meat and seafood source and distributor analysis 1.1 Kitchen Basics | Food Safety | USA cuisine 2.1 Food Economics | Reducing Food Waste | South Korean cuisine 1.2 Kitchen Basics | Knife Skills | USA cuisine 2.2 Food Economics | Reducing Food Waste | South Korean cuisine 1.3 Kitchen Basic | Meal Planning & Cooking for a Crowd | United Kingdom Cuisine 2.3 Food Economics | Value of Eating Local | French & Vietnamese Cuisine 1.4 Nutrition Science | Ingredient Investigation | United Kingdom Cuisine 2.4 Food Economics | Slow Food | French Cuisine 1.5 Nutrition Science | Food Lifestyle with Medical Conditions | Singaporean Cuisine 2.5 Food Industry Operations | Tourism & Hospitality | Italian Cuisine 1.6 Nutrition Science | Healing Foods | Singaporean Cuisine 2.6 Food Industry Operations | Sourcing | Italian Cuisine 1.7 Entrepreneurship | Restaurant Business Models 2.7 Entrepreneurship | Business Planning 1.8 Entrepreneurship -

National Dish

National dish From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_dish A national dish is a culinary dish that is strongly associated with a particular country.[1] A dish can be considered a national dish for a variety of reasons: • It is a staple food, made from a selection of locally available foodstuffs that can be prepared in a distinctive way, such as fruits de mer, served along the west coast of France.[1] • It contains a particular 'exotic' ingredient that is produced locally, such as the South American paprika grown in the European Pyrenees.[1] • It is served as a festive culinary tradition that forms part of a cultural heritage—for example, barbecues at summer camp or fondue at dinner parties—or as part of a religious practice, such as Korban Pesach or Iftar celebrations.[1] • It has been promoted as a national dish, by the country itself, such as the promotion of fondue as a national dish of Switzerland by the Swiss Cheese Union (Schweizerische Käseunion) in the 1930s. Pilaf (O'sh), a national dish in the cuisines of Central Asia National dishes are part of a nation's identity and self-image.[2] During the age of European empire-building, nations would develop a national cuisine to distinguish themselves from their rivals.[3] According to Zilkia Janer, a lecturer on Latin American culture at Hofstra University, it is impossible to choose a single national dish, even unofficially, for countries such as Mexico, China or India because of their diverse ethnic populations and cultures.[2] The cuisine of such countries simply cannot be represented by any single national dish. -

A Celebration

[email protected] TUESDAY 19 MAY 2015 • www.thepeninsulaqatar.com • 4455 7741 The inaugural Katara Arabic Novel Festival which opened yesterday promises to be an effective platform to promote Arabic novels globally and encourage cultural interaction among Arab novelists. RAMADA ENCORE LAUNCHES THE BIG FISHERMAN’S HOOK UP P | 4 FASHION SASHAYS FOR FIGHT AGAINST AIDS P | 8 A CELEBRATION MY MUSIC IS OF ARABIC NOVEL DEDICATED TO THE HEART: MITHOON P | 2-3 P | 11 | TUESDAY 19 MAY 2015 | 02 CULTURE The four-day festival hosts a number of cultural, literary, media and art figures from Qatar and other Arab countries and includes symposia, exhibitions and events celebrating the Arabic novel. Katara pushes Arabic novel forward RAYNALD C RIVERA wider cultural interaction among promi- nent figures and intellectuals. he inaugural Katara Arabic “I hope that the Katara Prize for Novel Festival which Arabic Novel will usher in a new era for opened yesterday prom- Arabic novel,” added Dr Al sulaiti. ises to act as an effec- The opening day also saw the tive platform in promoting inauguration of the Katara Centre for TArabic novels globally and encourag- Arabic Novel, one of the vital projects ing cultural interaction among Arab in Katara which is the first of its kind in novelists. the region as it specifically focuses on The four-day festival hosts a number Arabic novels and provides services for of cultural, literary, media and art figures Arab novelists. The centre is equipped from Qatar and other Arab countries with a library which houses modern and includes symposia, exhibitions and and old Arabic novels as well as films events celebrating the Arabic novel. -

Business Plan for a U.S. Based Healthy and Organic Ethnic Korean Quick-Service Restaurant

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones Fall 2012 Business Plan for a U.S. Based Healthy and Organic Ethnic Korean Quick-Service Restaurant Daniel W. Kim University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Food and Beverage Management Commons Repository Citation Kim, Daniel W., "Business Plan for a U.S. Based Healthy and Organic Ethnic Korean Quick-Service Restaurant" (2012). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1471. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/3553708 This Professional Paper is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Professional Paper in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Professional Paper has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Business Plan for a U.S. Based Healthy and Organic Ethnic Korean Quick-Service Restaurant by Daniel W. Kim Bachelor of Science Hotel Administration University of Nevada, Las Vegas August, 2004 A professional paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Hotel Administration William F. Harrah College of Hotel Administration Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December, 2012 Chair: Dr. -

The School Meal System and School-Based Nutrition Education in Korea

J Nutr Sci Vitaminol, 61, S23–S24, 2015 The School Meal System and School-Based Nutrition Education in Korea Taejung WOO Changwon National University, 20 Changwondaehak-ro, Uichang-gu, Chanwon-si, Gyeongnam, Korea Summary Since the school meal was first served in Korea in 1953, there have been many changes, particularly during the last decade. Recently, the representative features of the school meal system became free school meals for all pupils in elementary school and a nutri- tion teacher system in schools. These policies were suggested to implement more and more the educational role of the school meal. The rate of schools serving school meals reached 100% as of 2013, and 99.6% students eat a school meal each school day. Nutrition teachers were assigned to schools from 2007, and 4,704 (47.9%) nutrition teachers of all nutrition employees were employed in schools as of 2013. At present, various nutrition education materials are being development by local education offices and government agencies, and various education activities are being implemented spiritedly. The ultimate goal of school meals and school-based nutrition education are as follows: 1) improvement of the health of students; 2) promotion of the traditional Korean diet; and 3) extension of opportunities for a healthier dietary life. Key Words school meal, nutrition education, Korea The Latest Policies in School Meal System in schools has been established, but various education The purpose of this article is to give an overview of activities are being implemented spiritedly. Nutrition the latest school meal system and School-based nutri- education is being implemented mainly using discre- tion education in Korea. -

Potato - Wikipedia

8/16/2018 Potato - Wikipedia Potato The potato is a starchy, tuberous crop from the perennial nightshade Solanum tuberosum. Potato may be applied to Potato both the plant and the edible tuber.[2] Common or slang terms for the potato include tater and spud. Potatoes have become a staple food in many parts of the world and an integral part of much of the world's food supply. Potatoes are the world's fourth-largest food crop, following maize (corn), wheat, and rice.[3] Tubers produce glycoalkaloids in small amounts. If green sections (sprouts and skins) of the plant are exposed to light the tuber can produce a high enough concentration of glycoalkaloids to affect human health.[4][5] In the Andes region of South America, where the species is indigenous, some other closely related species are cultivated. Potatoes were introduced to Europe in the second half of the 16th century by the Spanish. Wild potato species can be found throughout the Americas from the United States to southern Chile.[6] The potato was originally believed to have been Potato cultivars appear in a variety of domesticated independently in multiple locations,[7] but later genetic testing of the wide variety of cultivars and wild colors, shapes, and sizes. species proved a single origin for potatoes in the area of present-day southern Peru and extreme northwestern Bolivia (from a species in the Solanum brevicaule complex), where they were domesticated approximately 7,000–10,000 years Scientific classification [8][9][10] [9] ago. Following millennia of selective breeding, there are now over a thousand different types of potatoes. -

DISCOVER City Limitless® FIRST AUTISM CERTIFIED CITY in the U.S

2020 DISCOVER city limitless® FIRST AUTISM CERTIFIED CITY IN THE U.S. NEW FINDS ON THE FRESH FOODIE TRAIL® BUCKLE UP FOR ADVENTURE LODGING, GOLF, EVENTS, DINING, MAPS AND MORE MESA • QUEEN CREEK • APACHE TRAIL • TONTO NATIONAL FOREST 2020 Visitors Guide | | II A LETTER FROM OUR MAYOR MESA BY THE WELCOME TO MESA NUMBERS 511,344 Population (Estimated, 2019) 3rd Largest City in Arizona 35th Largest City in the U.S. 325+ Sunny Days per Year (on average) 40+ As the Mayor of this great city, I am business community have undergone Golf Courses honored to welcome you to Mesa, training to recognize those on the (200+ in Greater Arizona! From a rising arts and spectrum and be able to provide an Phoenix) innovation district in Downtown Mesa excellent experience for all. to the most beautiful desert in the West, Mesa has not just something Changes are taking place in our for everyone, it has everything. For downtown district. Several Main 55 Parks example, the third largest city in Street buildings have new facades, Arizona is home to the Mesa Marathon restoring their historic brick fronts where you can qualify for the Boston with modern touches. This year, you Marathon and then wind down at one will also see new structures taking of our fine hotels or celebrate at one shape with housing and retail projects 900+ of our local restaurants or breweries. in various stages of development. Restaurants The new decade rings in an exciting Mesa also shares an undeniably era for Mesa as Arizona State authentic Arizona experience out on University breaks ground on ASU@ 5,579 our trails and parks where you can MesaCityCenter, the innovative home Hotel Rooms mountain bike, hike or horseback of their film school and augmented in Mesa ride.