Tribal College Libraries and the Federal Depository Library Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educating the Mind and Spirit 2006-2007

Educating the Mind and Spirit 2006-2007 ANNUAL REPORT ENVISIONING OUR POWERFUL FUTURE MISSION The American Indian College Fund’s mission is to raise scholarship funds for American Indian students at qualified tribal colleges and universities and to generate broad awareness of those institutions and the Fund itself. The organization also raises money and resources for other needs at the schools, including capital projects, operations, endowments or program initiatives, and it will conduct fundraising and related activities for any other Board- directed initiatives. CONTENTS President’s Message 2 Chairman’s Message 3 Tribal Colleges and Students by State 4 The Role of Tribal Colleges and Universities 5 Scholarship Statistics 6 Our Student Community 7 Scholarships 8 Individual Giving 9 Corporations, Foundations, and Tribes 10 Special Events and Tours 12 Student Blanket Contest 14 Public Education 15 Corporate, Foundation, and Tribal Contributors 16 Event Sponsors 17 Individual Contributors 18 Circle of Vision 19 Board of Trustees 20 American Indian College Fund Staff 21 Independent Auditor’s Report 22 Statement of Financial Position 23 Statement of Activities 24 Statement of Cash Flows 25 Notes to Financial Statement 26 Schedule of Functional Expenses 31 1 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The Circle of Life, the Circle of Hope Dear Friends and Relatives, ast year I wrote about the challenges that faced Gabriel plans to graduate with a general studies the nation and how hope helps us endure those degree from Stone Child College, then transfer to the L -

Student Competition Winner

STUDENT COMPETITION WINNER: KNOWLEDGE BOWL - 5 PARTICIPANTS 1st Place Team Aaniiih Nakoda College] 2nd Place Team Fort Peck Community College 3rd Place Team Institute of Am. Indian Arts BUSINESS BOWL 1st Place College of Menominee Nation 2nd Place Sinte Gleska University 3rd Place Oglala Lakota College WEB PAGE DESIGN 1st Place - Individual Steam Team Navajo Technical University 2nd Place - Individual Fort Peck Community College 3rd Place - Individual Navajo Technical University CRITICAL INQUIRY - TEAM # 1ST Place - Team (Traveling Trophy) Dine College 2nd Place - Team Northwest Indian College 3rd Place - Team Turtle Mountain Community College HANDGAMES - 12 participants 1st Place - Team Little Priest College 2nd Place - Team Oglala Lakota College 3rd Place - Team United Tribes Technical Best Hider Mariah Provincial Oglala Lakota College Best Guesser Jessica LaTray Little Priest College Best Group Singers Oglala Lakota College Most enthistic Haskell Indian Nations College Sponsorship Fond Lu Lac Tribal & Comm. College Best Dressed SIPI SCIENCE BOWL - 3 PARTICIPANTS 1st Place - Team Gabe Yellow Hawk, Joanne Thompson Oglala Lakota College Larissa Red Eagle 2nd Place - Team Lee Voight, Caley Fox Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College 3rd Place - Team Darrell Yazzie, LeTanyaThinn, Jordan Mescal Dine College SCIENCE POSTER 1st place - individual Ashley Hall Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College Comparsion of Yield of Various Cultivars of Amelanchier on Fort Berthold Reservation 2nd Place - individual Patrisse Vasek Oglala Lakota College "Bioavailable and Leachable -

Tribal College and University Funding

ISSUE BRIEF MINORITY-SERVING INSTITUTIONS Series May 2016 AUTHOR ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Tribal College and University We would like to thank the Amer- ican Indian Higher Education Consortium (AIHEC), the American Funding: Tribal Sovereignty Indian College Fund, and the tribal colleges and universities that con- at the Intersection of Federal, sulted on this project. AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS State, and Local Funding Christine A. Nelson (Diné and Laguna Pueblo) is a postdoctoral by Christine A. Nelson and Joanna R. Frye fellow at the University of New Mex- ico Division for Equity and Inclu- sion and the Center for Education Policy Research. Joanna R. Frye is a research fellow at the ADVANCE Program at the University of Michigan. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As a general consensus, postsecondary credentials Tribal colleges and universities (TCUs) continue to are key to ensuring that the United States produces provide a transformative postsecondary experience economically competitive and contributing members and education for the Indigenous population and to society. It should also be stated that postsecondary non-Native students from in and around Native opportunities stretch beyond traditionally recognized communities. The 37 TCUs enroll nearly 28,000 full- needs; they also contribute to the capacity building of and part-time students annually. TCUs, which primarily sovereign tribal nations. The Native population has serve rural communities without access to mainstream increased 39 percent from 2000 to 2010, but Native postsecondary institutions, have experienced student enrollment remains static, representing just 1 enrollment growth over the last decade, increasing percent of total postsecondary enrollment (Stetser and nearly 9 percent between academic year (AY) 2002–03 Stillwell 2014; Norris, Vines, and Hoeffel 2012). -

Tcus As Engaged Institutions

Building Strong Communities Tribal Colleges as Engaged Institutions Prepared by: American Indian Higher Education Consortium & The Institute for Higher Education Policy A product of the Tribal College Research and Database Initiative Building Strong Communities: Tribal Colleges as Engaged Institutions APRIL 2001 American Indian Higher Education Consortium The Institute for Higher Education Policy A product of the Tribal College Research and Database Initiative, a collaborative effort between the American Indian Higher Education Consortium and the American Indian College Fund ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is the fourth in a series of policy reports produced through the Tribal College Research and Database Initiative. The Initiative is supported in part by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Native Ameri- cans (ANA) and the Pew Charitable Trusts. A collaborative effort between the American Indian Higher Education Consor- tium (AIHEC) and the American Indian College Fund, the project is a multi-year effort to improve understanding of Tribal Colleges. AIHEC would also like to thank the W.K. Kellogg Foundation for its continued support. This report was prepared by Alisa Federico Cunningham, Senior Research Analyst, and Christina Redmond, Research Assis- tant, at The Institute for Higher Education Policy. Jamie Merisotis, President, Colleen O’Brien, Vice President, and Deanna High, Project Editor, at The Institute, as well as Veronica Gonzales, Jeff Hamley, and Sara Pena at AIHEC, provided writing and editorial assistance. We also would like to acknowledge the individuals and organizations who offered information, advice, and feedback for the report. In particular, we would like to thank the many Tribal College presidents who read earlier drafts of the report and offered essential feedback and information. -

ACCC Inventory of College Programs Offered

Colleges Serving Aboriginal Learners and Communities 2010 Environmental Scan Programs offered by Aboriginal Colleges and Institutes in Partnership with Mainstream Institutions BRITISH COLUMBIA Aboriginal Apprenticeship and Industry Training (AAIT) (Kamloops, BC) Program accredited through Thompson Rivers University: Introduction to Welding and Vocational Skills Upgrading Program Other programs: Residential Building Maintenance Worker Program Entry Level Carpentry Access to Trades Trades Math Project Management Building Inspector AAIT Workshops Chemainus Native College (Cowichan Valley, BC) Programs accredited through Vancouver Island University: * The College has an affiliation agreement in place with Vancouver Island University, meaning courses and programs are transferable to VIU: UCEP/University College Education Preparation Programs (Math, English, First Nation Studies, and CAP) Hul’qumi’num En’owkin Centre (Penticton, BC) Programs accredited through Nicola Valley Institute of Technology: College Readiness program Nsyilxcen Language program Programs accredited through University of British Columbia: Aboriginal Access Program Developmental Standard Term Certificate Baccalaureate Degree in Indigenous Studies Programs accredited through University of Victoria: Certificate in Aboriginal Language Revitalization Indigenous Fine Arts program Other program: National Aboriginal Professional Artist Training Program Gitksan Wet’suwet’en Education Society (Hazelton, B.C) Practical Nurse program First Nations High School/Adult Learning -

PART C—1994 INSTITUTIONS Sec

Q:\COMP\AGRES\Equity In Educational Land-grant Status Act Of 1994.xml EQUITY IN EDUCATIONAL LAND-GRANT STATUS ACT OF 1994 [[Part C of title V of the Improving America’s Schools Act of 1994 (Public Law 103–382; 108 Stat. 4048; 7 U.S.C. 301 note]] [As Amended Through P.L. 113–79, Enacted February 7, 2014] [Equity in Educational Land-Grant Status Act of 1994] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PART C—1994 INSTITUTIONS Sec. 531. Short title. Sec. 532. Definition. Sec. 533. Land-grant status for 1994 institutions. Sec. 534. Appropriations. Sec. 535. Institutional capacity building grants. Sec. 536. Research grants. PART C—1994 INSTITUTIONS SEC. 531. ø7 U.S.C. 301 note¿ SHORT TITLE. This part may be cited as the ‘‘Equity in Educational Land- Grant Status Act of 1994’’. SEC. 532. ø7 U.S.C. 301 note¿ DEFINITION. 2 As used in this part, the term ‘‘1994 Institutions’’ means any one of the following colleges: (1) Bay Mills Community College. (2) Blackfeet Community College. (3) Cankdeska Cikana Community College. (4) College of Menominee Nation. (5) Crownpoint Institute of Technology. (6) D-Q University. (7) Dine College. (8) Chief Dull Knife Memorial College. (9) Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College. (10) Fort Belknap College. (11) Fort Berthold Community College. (12) Fort Peck Community College. (13) Haskell Indian Nations University. (14) Institute of American Indian and Alaska Native Cul- ture and Arts Development. (15) Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College. (16) Leech Lake Tribal College. 1 This table of contents is not part of the Act but is included for user convenience. -

ARP A2 TCCU Allocation Table (PDF)

Allocations Under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, pursuant to Section 314(a)(2) of the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2021 Institutional names are listed in alphabetical order. Once you find your institution’s name, scan to the far right of the chart to find your institution’s TCCU allocation. Information for HBCU, MSI, and SIP allocations are not included in this table. For information on how these allocation amounts were determined, refer to the “Methodology for Calculating Allocations Under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 pursuant to Section 314(a)(2) of the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2021” document. Total Allocation OPEID School State 84.425K 02517500 Aaniiih Nakoda College MT $ 2,543,979.00 03066600 Bay Mills Community College MI $ 3,479,617.00 02510600 Blackfeet Community College MT $ 3,875,564.00 02236500 Cankdeska Cikana Community College ND $ 2,577,946.00 02545200 Chief Dull Knife College MT $ 2,767,713.00 03125100 College of Menominee Nation WI $ 2,586,141.00 04224900 College of the Muscogee Nation OK $ 3,263,744.00 00824600 Dine College AZ $ 10,176,741.00 03129100 Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College MN $ 2,678,425.00 02343000 Fort Peck Community College MT $ 3,502,183.00 02553700 Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College ND $ 2,729,945.00 01043800 Haskell Indian Nations University KS $ 7,745,009.00 03461300 Ilisagvik College AK $ 2,197,333.00 02146400 Institute of American Indian and Alaska Native Culture and Arts Developm NM $ 4,107,587.00 04164700 -

South Dakota Space Grant Consortium South Dakota School of Mines & Technology Edward F

South Dakota Space Grant Consortium South Dakota School of Mines & Technology Edward F. Duke, Ph.D. (605) 394-1975 http://sdspacegrant.sdsmt.edu Grant Number NNX10AL27H PROGRAM DESCRIPTION The National Space Grant College and Fellowship Program consists of 52 state-based, university-led Space Grant Consortia in each of the 50 states plus the District of Columbia and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Annually, each consortium receives funds to develop and implement student fellowships and scholarships programs; interdisciplinary space-related research infrastructure, education, and public service programs; and cooperative initiatives with industry, research laboratories, and state, local, and other governments. Space Grant operates at the intersection of NASA’s interest as implemented by alignment with the Mission Directorates and the state’s interests. Although it is primarily a higher education program, Space Grant programs encompass the entire length of the education pipeline, including elementary/secondary and informal education. The South Dakota Space Grant Consortium is a Capability Enhancement Consortium funded at a level of $660,000 for fiscal year 2010. PROGRAM GOALS Consortium Management: To ensure quality and fairness in all Consortium programs and alignment with the needs of NASA, the member and affiliate organizations, and the state of South Dakota. Fellowship/Scholarship: To administer a fellowship/scholarship program that offers educational and research opportunities to students from diverse backgrounds who are pursuing degrees in fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) that align with NASA’s mission and those of SDSGC members and affiliates. Research Infrastructure: To promote the improvement of research programs and capabilities of Consortium members with an emphasis on the fields of aerospace, earth science, and supporting STEM disciplines. -

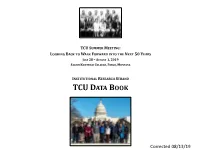

Tcu Data Book

TCU SUMMER MEETING: LOOKING BACK TO WALK FORWARD INTO THE NEXT 50 YEARS JULY 28 – AUGUST 1, 2019 SALISH KOOTENAI COLLEGE, PABLO, MONTANA INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH STRAND TCU DATA BOOK Corrected 08/13/19 Table of Contents Enrollment Aggregate Regional Major Group Enrollment Aggregate Regional First-Time Entering Students Aggregate Regional First Year Retention Aggregate Regional General Student Population Aggregate Regional Faculty Demographics Faculty Salaries Aggregate TCU Enrollment 20,000 19,694 19,326 19,000 18,770 18,000 18,149 17,596 17,000 16,512 16,000 15,827 15,426 15,512 15,482 15,367 15,000 14,883 14,000 Fall 2007 Fall 2008 Fall 2009 Fall 2010 Fall 2011 Fall 2012 Fall 2013 Fall 2014 Fall 2015 Fall 2016 Fall 2017 Fall 2018 Aggregate TCU Enrollment by Gender Ethnicity, and Status 35% 33% 32% 30% 25% 21% 22% 21% 21% 20% 15% 10% 10% 10% 5% 6% 5% 5% 3% 4% 3% 3% 2% 0.01% 0.02% 0.01% 0% 0% Male Female Other Male Female Other Male Female Other Male Female Other AI/AN Non-Native AI/AN Non-Native Full-Time Part-Time Fall 2008 Fall 2018 Institution Name Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall Fall 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Aaniiih Nakoda College 259 175 161 239 168 293 214 229 188 151 291 228 177 135 133 Bay Mills C.C. 547 519 559 422 432 563 596 577 536 526 493 461 409 448 477 Blackfeet C.C. -

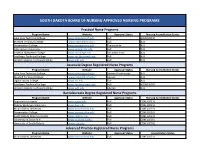

Practical Nurse Programs

SOUTH DAKOTA BOARD OF NURSING APPROVED NURSING PROGRAMS Practical Nurse Programs Program Name Website Approval Status Nursing Accreditation Status Lake Area Technical College www.lakeareatech.edu Full ACEN (2021) Mitchell Technical College www.mitchelltech.edu Full N/A Presentation College www.presentation.edu Prerequisite N/A Sinte Gleska University www.sintegleska.edu Full N/A Sisseton Wahpeton College www.swcollege.edu Voluntary Hold N/A Southeast Technical College www.southeasttech.edu Full N/A Western Dakota Technical College www.wdt.edu Full N/A Associate Degree Registered Nurse Programs Program Name Website Approval Status Nursing Accreditation Status Lake Area Technical College www.lakeareatech.edu Interim (Continuing) N/A Mitchell Technical College www.mitchelltech.edu Interim N/A Oglala Lakota College www.olc.edu Full N/A Southeast Technical College www.southeasttech.edu Full ACEN (2020) Western Dakota Technical College www.wdt.edu Interim N/A Baccalaureate Degree Registered Nurse Programs Program Name Website Approval Status Nursing Accreditation Status Augustana Univesity www.augie.edu Full CCNE (2021) Dakota Wesleyan University www.dwu.edu Full CCNE (2021) Mount Marty University www.mountmarty.edu Full CCNE (2022) Presentation College www.presentation.edu Full CCNE (2020) South Dakota State University www.sdstate.edu Full CCNE (2021) University of Sioux Falls www.usiouxfalls.edu Full CCNE (2026) University of South Dakota www.usd.edu Full CCNE (2028) Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Programs Program Name Website Approval -

FY 2012 Grantees for Title III Part a and Part F Under the American

FY 2012 Grantees for Discretionary Funding Title III, Part A, American Indian Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities Program Award Number State Institution Grant Award $ P031T100300 MI Bay Mills Community College 644,027 P031T100301 MT Blackfeet Community College 786,915 P031T100302 ND Cankdeska Cikana Community College 515,644 P031T100303 MT Chief Dull Knife College 545,364 P031T100304 WI College of Menominee Nation 228,721 P031T100305 AZ Dine College 2,162,164 P031T100306 MN Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College 500,000 P031T100307 MT Aaniiih Nakoda College (Fort Belknap College) 500,000 P031T100308 ND Fort Berthold Community College 500,000 P031T100309 MT Fort Peck Community College 665,016 P031T100310 KS Haskell Indian Nations University 1,192,493 P031T100311 AK Ilisagvik College 500,000 P031T100312 NM Institute of American Indian Arts 570,711 P031T110333 MI Keweenaw Bay Ojibwa Community College 500,000 P031T100313 WI Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College 537,132 P031T100332 MN Leech Lake Tribal College 500,000 P031T100315 MT Little Big Horn College 659,308 P031T100316 NE Little Priest Tribal College 25,002 P031T100317 NM Navajo Technical College 1,614,348 P031T100318 NE Nebraska Indian Community College 500,000 P031T100319 WA Northwest Indian College 1,102,933 P031T100320 SD Oglala Lakota College 1,651,227 P031T110334 MI Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College 500,000 P031T100321 MT Salish Kootenai College 1,175,771 P031T100322 SD Sinte Gleska University 956,783 P031T100323 SD Sisseton Wahpeton College 500,000 P031T100324 -

National Center for Education Statistics

Image description. Cover Image End of image description. NATIONAL CENTER FOR EDUCATION STATISTICS What Is IPEDS? The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) is a system of survey components that collects data from about 6,400 institutions that provide postsecondary education across the United States. These data are used at the federal and state level for policy analysis and development; at the institutional level for benchmarking and peer analysis; and by students and parents, through the College Navigator (https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/), an online tool to aid in the college search process. Additional information about IPEDS can be found on the website at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds. What Is the Purpose of This Report? The Data Feedback Report is intended to provide institutions a context for examining the data they submitted to IPEDS. The purpose of this report is to provide institutional executives a useful resource and to help improve the quality and comparability of IPEDS data. What Is in This Report? The figures in this report provide a selection of indicators for your institution to compare with a group of similar institutions. The figures draw from the data collected during the 2018-19 IPEDS collection cycle and are the most recent data available. The inside cover of this report lists the pre-selected comparison group of institutions and the criteria used for their selection. The Methodological Notes at the end of the report describe additional information about these indicators and the pre-selected comparison group. Where Can I Do More with IPEDS Data? Each institution can access previously released Data Feedback Reports from 2005 and customize this 2019 report by using a different comparison group and IPEDS variables of its choosing.