Environmental Policies and Practice in China’S Banking Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEACHERS' RETIREMENT SYSTEM of the STATE of ILLINOIS 2815 West Washington Street I P.O

Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois Compliance Examination For the Year Ended June 30, 2020 Performed as Special Assistant Auditors for the Auditor General, State of Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois Compliance Examination For the Year Ended June 30, 2020 Table of Contents Schedule Page(s) System Officials 1 Management Assertion Letter 2 Compliance Report Summary 3 Independent Accountant’s Report on State Compliance, on Internal Control over Compliance, and on Supplementary Information for State Compliance Purposes 4 Independent Auditors’ Report on Internal Control over Financial Reporting and on Compliance and Other Matters Based on an Audit of Financial Statements Performed in Accordance with Government Auditing Standards 8 Schedule of Findings Current Findings – State Compliance 10 Supplementary Information for State Compliance Purposes Fiscal Schedules and Analysis Schedule of Appropriations, Expenditures and Lapsed Balances 1 13 Comparative Schedules of Net Appropriations, Expenditures and Lapsed Balances 2 15 Comparative Schedule of Revenues and Expenses 3 17 Schedule of Administrative Expenses 4 18 Schedule of Changes in Property and Equipment 5 19 Schedule of Investment Portfolio 6 20 Schedule of Investment Manager and Custodian Fees 7 21 Analysis of Operations (Unaudited) Analysis of Operations (Functions and Planning) 30 Progress in Funding the System 34 Analysis of Significant Variations in Revenues and Expenses 36 Analysis of Significant Variations in Administrative Expenses 37 Analysis -

OSB Representative Participant List by Industry

OSB Representative Participant List by Industry Aerospace • KAWASAKI • VOLVO • CATERPILLAR • ADVANCED COATING • KEDDEG COMPANY • XI'AN AIRCRAFT INDUSTRY • CHINA FAW GROUP TECHNOLOGIES GROUP • KOREAN AIRLINES • CHINA INTERNATIONAL Agriculture • AIRBUS MARINE CONTAINERS • L3 COMMUNICATIONS • AIRCELLE • AGRICOLA FORNACE • CHRYSLER • LOCKHEED MARTIN • ALLIANT TECHSYSTEMS • CARGILL • COMMERCIAL VEHICLE • M7 AEROSPACE GROUP • AVICHINA • E. RITTER & COMPANY • • MESSIER-BUGATTI- CONTINENTAL AIRLINES • BAE SYSTEMS • EXOPLAST DOWTY • CONTINENTAL • BE AEROSPACE • MITSUBISHI HEAVY • JOHN DEERE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRIES • • BELL HELICOPTER • MAUI PINEAPPLE CONTINENTAL • NASA COMPANY AUTOMOTIVE SYSTEMS • BOMBARDIER • • NGC INTEGRATED • USDA COOPER-STANDARD • CAE SYSTEMS AUTOMOTIVE Automotive • • CORNING • CESSNA AIRCRAFT NORTHROP GRUMMAN • AGCO • COMPANY • PRECISION CASTPARTS COSMA INDUSTRIAL DO • COBHAM CORP. • ALLIED SPECIALTY BRASIL • VEHICLES • CRP INDUSTRIES • COMAC RAYTHEON • AMSTED INDUSTRIES • • CUMMINS • DANAHER RAYTHEON E-SYSTEMS • ANHUI JIANGHUAI • • DAF TRUCKS • DASSAULT AVIATION RAYTHEON MISSLE AUTOMOBILE SYSTEMS COMPANY • • ARVINMERITOR DAIHATSU MOTOR • EATON • RAYTHEON NCS • • ASHOK LEYLAND DAIMLER • EMBRAER • RAYTHEON RMS • • ATC LOGISTICS & DALPHI METAL ESPANA • EUROPEAN AERONAUTIC • ROLLS-ROYCE DEFENCE AND SPACE ELECTRONICS • DANA HOLDING COMPANY • ROTORCRAFT • AUDI CORPORATION • FINMECCANICA ENTERPRISES • • AUTOZONE DANA INDÚSTRIAS • SAAB • FLIR SYSTEMS • • BAE SYSTEMS DELPHI • SMITH'S DETECTION • FUJI • • BECK/ARNLEY DENSO CORPORATION -

Integration of International Financial Regulatory Standards for the Chinese Economic Area: the Challenge for China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan Lawrence L.C

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 20 Issue 1 Fall Fall 1999 Integration of International Financial Regulatory Standards for the Chinese Economic Area: The Challenge for China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan Lawrence L.C. Lee Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the International Law Commons, International Trade Commons, Law and Economics Commons, and the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence L.C. Lee, Integration of International Financial Regulatory Standards for the Chinese Economic Area: The hC allenge for China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, 20 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 1 (1999-2000) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. ARTICLES Integration of International Financial Regulatory Standards for the Chinese Economic Area: The Challenge for China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan Lawrence L. C. Lee* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 2 II. ORIGINS OF THE CURRENT FINANCIAL AND BANKING SYSTEMS IN THE CHINESE ECONOMIC AREA ............................................................ 11 * Lawrence L. C. Lee is Assistant Professor at Ming Chung University School of Law (Taiwan) and Research Fellow at Columbia University School of Law. S.J.D. 1998, Univer- sity of Wisconsin-Madison Law School; LL.M. 1996, American University Washington College of Law; LL.M. 1993, Boston University School of Law; and LL.B. 1991, Soochow University School of Law (Taiwan). Portions of this article were presented at the 1999 Con- ference of American Association of Chinese Studies and the 1997 University of Wisconsin Law School Symposium in Legal Regulation of Cross-Straits Commercial Activities among Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China. -

Non-Governmental Organizations in China

Report Non-Governmental Organizations in China May, 2005 Andreas Edele Geneva, Switzerland Programme on NGOs & Civil Society Centre for Applied Studies in International Negotiations Centre d'études pratiques de la négociation internationale Centre for Applied Studies in Andreas Edele, Research Associate, prepared this report for the Programme International Negotiations on NGOs and Civil Society of the Centre for Applied Studies in International C.P. 1340 Negotiation. Av. de la Paix 7 bis 1207 Genève The Programme on NGOs and Civil Society Switzerland Worldwide, the role of civil society has been increasing at rapid speed. Non- governmental organizations (NGOs) have become significant and influential T +41 22 730 8675/76 players and generate much interest. Created in 1986, the Programme on F +41 22 730 8690 Non-Governmental Organizations and Civil Society aims at contributing [email protected] towards a better understanding of NGOs and the solutions of complex and www.casin.ch conflictive societal problems involving NGOs. The opinions expressed in this paper reflect only those of the author and not of the institutions to which he/she is or was affiliated. Copyright CASIN © May 2005 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................... 2 2. USE OF THE TERM NGO IN CHINA..................................................................................................... 2 3. SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND LEGAL ENVIRONMENT FOR NGOS IN CHINA........................................... -

中國中車股份有限公司 Crrc Corporation Limited

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. 中 國 中 車 股 份 有 限 公 司 CRRC CORPORATION LIMITED (a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1766) US$600,000,000 Zero Coupon Convertible Bonds due 2021 Stock code: 5613 2018 INTERIM RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors of CRRC Corporation Limited (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the unaudited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the six months ended 30 June 2018. This announcement, containing the main text of the 2018 interim report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Stock Exchange”) in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcements of interim results. The 2018 interim report of the Company and its printed version will be published and delivered to the H shareholders of the Company and available for view on the websites of the Stock Exchange at http://www.hkex.com.hk and of the Company at http://www.crrcgc.cc on or before 30 September 2018. By order of the Board CRRC Corporation Limited Liu Hualong Chairman Beijing, the PRC 24 August 2018 As at the date of this announcement, the executive directors of the Company are Mr. -

Industrial Bank Co., Ltd. Amount Issued Usd600m; Eur300m (Usd343m)

Green Bond Fact Sheet Industrial Bank Co., Ltd Date: 19 November 2018 Issue date: 20-Nov-2018 Maturity date: 20-Nov-2021 Tenor: 3 years Issuer Name Industrial Bank Co., Ltd. Amount Issued USD600m; EUR300m (USD343m) Country of risk China CBI Database Included Issuer Type1 Financial Corporate Bond Type Senior secured Green Bond Framework Link to Green Bond Second party opinion CICERO Framework Certification Standard Wind, Solar, Low Carbon Assurance report N/A Transport Certification Verifier Sustainalytics Green bond rating N/A Use of Proceeds ☒ Energy ☒ Solar ☐ Biofuels ☐ Energy storage ☒ Onshore wind ☐ Bioenergy ☐ Energy performance ☐ Offshore wind ☐ Waste to energy ☐ Infrastructure ☐ Geothermal ☐ District heating ☐ Industry: components ☐ Hydro ☐ Electricity grid ☐ Adaptation & resilience ☐ Tidal ☐ Buildings ☐ Certified Buildings ☐ Water performance ☐ Industry: components ☐ HVAC systems ☐ Energy storage/meters ☐ Adaptation & resilience ☐ Energy performance ☐ Other energy related ☒ Transport ☐ Electric vehicles ☐ Freight rolling stock ☐ Transport logistics ☐ Low emission vehicles ☐ Coach / public bus ☐ Infrastructure ☐ Bus rapid transit ☐ Bicycle infrastructure ☐ Industry: components ☒ Passenger trains ☐ Energy performance ☐ Adaptation & resilience ☒ Urban rail ☐ Water & wastewater ☐ Water distribution ☐ Storm water mgmt ☐ Infrastructure ☐ Water treatment ☐ Desalinisation plants ☐ Industry: components ☐ Wastewater treatment ☐ Erosion control ☐ Adaptation & resilience ☐ Water storage ☐ Energy performance ☐ Waste management ☐ Recycling ☐ -

Annual Report 2019 Mobility

(a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) Stock Code: 1766 Annual Report Annual Report 2019 Mobility 2019 for Future Connection Important 1 The Board and the Supervisory Committee of the Company and its Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management warrant that there are no false representations, misleading statements contained in or material omissions from this annual report and they will assume joint and several legal liabilities for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the contents disclosed herein. 2 This report has been considered and approved at the seventeenth meeting of the second session of the Board of the Company. All Directors attended the Board meeting. 3 Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu CPA LLP has issued standard unqualified audit report for the Company’s financial statements prepared under the China Accounting Standards for Business Enterprises in accordance with PRC Auditing Standards. 4 Liu Hualong, the Chairman of the Company, Li Zheng, the Chief Financial Officer and Wang Jian, the head of the Accounting Department (person in charge of accounting affairs) warrant the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the financial statements in this annual report. 5 Statement for the risks involved in the forward-looking statements: this report contains forward-looking statements that involve future plans and development strategies which do not constitute a substantive commitment by the Company to investors. Investors should be aware of the investment risks. 6 The Company has proposed to distribute a cash dividend of RMB0.15 (tax inclusive) per share to all Shareholders based on the total share capital of the Company of 28,698,864,088 shares as at 31 December 2019. -

Industrial Bank Co.,Ltd

INDUSTRIAL BANK CO.,LTD. INDUSTRIAL THE FIRST EPFI IN CHINA GREAT BANK LEADS TO A GREAT LIFE ANNUAL Add: No. 154 Hudong Road, Fuzhou, Fujian, P.R.C T e l : (86)591-87839338 R E F a x : (86)591-87842633 P P. C : 350003 O R www.cib.com.cn T ANNUAL REPORT THE FIRST EQUATOR PRINCIPLES FINANCIAL INSTITUTION (EPFI) IN CHINA 02 INDUSTRIAL BANK Important Notice The Company’s Board of Directors, Board of Supervisors, directors, supervisors and senior management members hereby warrant that the information contained in this report is free from false representation, misleading statement or material omission, and assume joint and several liabilities. The Company’s 2017 annual report and its abstract were reviewed and approved at the 8th meeting of the 9th session of the Board of Directors on April 24, 2018. The financial data and indicators contained in this annual report were prepared in compliance with the PRC Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. Unless otherwise specified, they represented the consolidated data, and the monetary sums expressed in RMB in this annual report. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Certified Public Accountants LLP has audited the Company’s 2017 financial statements in accordance with the Chinese Auditing Standards (“CAS”) and has issued a standard auditors’ report with unqualified opinions. The Company’s chairman Gao Jianping, president Tao Yiping and general manager of the financial department Li Jian hereby warrant that the financial statements in the 2017 annual report are true, accurate and complete. The plan of dividends distribution for ordinary shares for the reporting period considered by the Board of Directors: based on the total capital of 20,774,190,751 shares, cash dividend of RMB6.50 (inclusive of tax) should be distributed for every 10 ordinary shares. -

Pacer CSOP FTSE China A50 ETF Schedule of Investments July 31, 2020 (Unaudited) Shares Value COMMON STOCKS - 98.0% Agriculture - 1.6% Muyuan Foodstuff Co Ltd

Page 1 of 4 Pacer CSOP FTSE China A50 ETF Schedule of Investments July 31, 2020 (Unaudited) Shares Value COMMON STOCKS - 98.0% Agriculture - 1.6% Muyuan Foodstuff Co Ltd. - Class A 9,230 $ 120,977 Wens Foodstuffs Group Co Ltd. - Class A 4,660 15,857 136,834 Auto Manufacturers - 0.7% SAIC Motor Corp Ltd. - Class A 24,600 64,077 Banks - 23.7% Agricultural Bank of China Ltd. - Class H 352,300 163,039 Bank of China Ltd. - Class H 193,900 92,512 Bank of Communications Co Ltd. - Class A 184,100 125,556 China CITIC Bank Corp Ltd. - Class H 24,700 18,261 China Construction Bank Corp. - Class H 81,500 71,464 China Everbright Bank Co Ltd. - Class H 126,400 68,456 China Merchants Bank Co Ltd. - Class A 108,200 539,489 China Minsheng Banking Corp Ltd. - Class A 254,300 201,851 Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd. - Class A 198,400 140,993 Industrial Bank Co Ltd. - Class A 127,400 285,849 Ping An Bank Co Ltd. - Class A 75,000 143,348 Shanghai Pudong Development Bank Co Ltd. - Class A 132,300 196,379 2,047,197 Beverages - 17.9% Jiangsu Yanghe Brewery Joint-Stock Co Ltd. - Class A 4,000 77,398 Kweichow Moutai Co Ltd. - Class A 4,000 961,777 Wuliangye Yibin Co Ltd. - Class A 16,200 504,835 1,544,010 Building Materials - 1.6% Anhui Conch Cement Co Ltd. - Class H 15,900 139,921 Coal - 0.5% China Shenhua Energy Co Ltd. -

Made in China, Financed in Hong Kong

China Perspectives 2007/2 | 2007 Hong Kong. Ten Years Later Made in China, financed in Hong Kong Anne-Laure Delatte et Maud Savary-Mornet Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1703 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1703 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 avril 2007 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Anne-Laure Delatte et Maud Savary-Mornet, « Made in China, financed in Hong Kong », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2007/2 | 2007, mis en ligne le 08 avril 2008, consulté le 28 octobre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/1703 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.1703 © All rights reserved Special feature s e v Made In China, Financed i a t c n i e In Hong Kong h p s c r e ANNE-LAURE DELATTE p AND MAUD SAVARY-MORNET Later, I saw the outside world, and I began to wonder how economic zones and then progressively the Pearl River it could be that the English, who were foreigners, were Delta area. In 1990, total Hong Kong investments repre - able to achieve what they had achieved over 70 or 80 sented 80% of all foreign investment in the Chinese years with the sterile rock of Hong Kong, while China had province. The Hong Kong economy experienced an accel - produced nothing to equal it in 4,000 years… We must erated transformation—instead of an Asian dragon specialis - draw inspiration from the English and transpose their ex - ing in electronics, it became a service economy (90% of ample of good government into every region of China. -

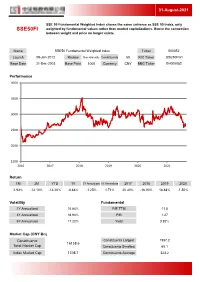

SSE50FI Weighted by Fundamental Values Rather Than Market Capitalizations

31-August-2021 SSE 50 Fundamental Weighted Index shares the same universe as SSE 50 Index, only SSE50FI weighted by fundamental values rather than market capitalizations. Hence the connection between weight and price no longer exists. Name SSE50 Fundamental Weighted Index Ticker 000052 Launch 09-Jan-2012 Review Semiannually Constituents 50 RIC Ticker .SSE50FWI Base Date 31-Dec-2003 Base Point 1000 Currency CNY BBG Ticker SH000052 Performance 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Return 1M 3M YTD 1Y 3Y Annualized 5Y Annualized 2017 2018 2019 2020 2.93% -13.10% -13.20% -8.88% -1.25% 1.71% 20.30% -16.00% 18.84% -1.50% Volatility Fundamental 1Y Annualized 15.84% P/E TTM 11.5 3Y Annualized 18.94% P/B 1.27 5Y Annualized 17.22% Yield 3.92% Market Cap (CNY Bn) Constituents Constituents Largest 1957.2 16158.6 Total Market Cap Constituents Smallest 65.1 Index Market Cap 1308.7 Constituents Average 323.2 31-August-2021 Exchange Breakdown Sector Breakdown 0.9% 4.8% Energy 4.5% 8.7% Materials Industrials 11.0% Consumer Disc. Shanghai Consumer Staples 5.7% Health Care 58.5% 4.9% Financials 1.0% 100.0% Information Tech. Telecom. Services Top 10 Constituents Ticker Name Sector Exchange Weight 601318 Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China Ltd Financials Shanghai 11.53% 601668 China State Construction Engineering Co Ltd Industrials Shanghai 7.69% 600036 China Merchants Bank Co Ltd Financials Shanghai 7.29% 601166 Industrial Bank Financials Shanghai 7.00% 601398 Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Ltd Financials Shanghai 5.73% 600016 China Minsheng Banking Corp Ltd Financials Shanghai 4.23% 600028 China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation Energy Shanghai 4.10% 600104 SAIC Motor Co Ltd Consumer Disc. -

China Environment Series 8 ISSUE 8, 2006

China EnvironmEnt SEries 8 iSSUE 8, 2006 Legal Advocacy in Environmental Public Participation Evolving Civil Society: From Environment to Health Reducing China’s Thirst for Foreign Oil Spurring Innovations for Clean Energy and Water Protection Water Conflict Resolution Energy: China and the North American Response Plus: Notes From the Field, Spotlight on NGOs EDITOR Jennifer L. Turner MANAGING EDITOR Juli S. Kim SPECIAL REPORT CO-EDITOR Timothy Hildebrandt PRODUCTION EDITORS Lianne Hepler and Jeremy Swanston RESEARCH ASSISTANTS Xixi Chen, Baohua Yan, and Louise Yeung ECSP STAFF Karin R. Bencala, Gib Clarke, Geoffrey D. Dabelko, Juli S. Kim, Meaghan Parker, Sean Peoples, Jennifer L. Turner, Alison Williams COVER PHOTO A view of the Nu River in Yunnan Province. © Ma Jun China EnvironmEnt SEries iSSUE 8, 2006 The China Environment Forum For nine years, the China Environment Forum—a sub-project within the Environmental Change and Security Program—has been active in creating programming, exchanges, and publications to encour- age dialogue among U.S., Chinese, and other Asian scholars, policymakers, businesses, and nongov- ernmental organizations on environmental and energy challenges in China. The China Environment Forum regularly brings together experts with diverse backgrounds and affiliations from the fields of environmental protection, China studies, energy, U.S. foreign policy, economics, and rural develop- ment. Through monthly meetings and the annual China Environment Series, the China Environment Forum aims to identify the most important environmental and sustainable development issues in China and explore creative ideas and opportunities for governmental and nongovernmental cooperation. The Wilson Center’s Asia Program periodically cosponsors meetings with the China Environment Forum.