Global Green New Deal Policy Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Research on Sustainable Business Models: Implications for Management Scholars

Journal of Environmental Sustainability Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 3 2019 The Evolution of Research on Sustainable Business Models: Implications for Management Scholars Sandra Rothenberg Rochester Institute of Technology, [email protected] Erinn G. Ryen Wells College, [email protected] Anne G. Sherman Rochester Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jes Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, and the Environmental Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rothenberg, Sandra; Ryen, Erinn G.; and Sherman, Anne G. (2019) "The Evolution of Research on Sustainable Business Models: Implications for Management Scholars," Journal of Environmental Sustainability: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jes/vol7/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Environmental Sustainability by an authorized editor of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Environmental Sustainability RESEARCH ARTICLE The Evolution of Research on Sustainable Business Models: Implications for Management Scholars Sandra Rothenberg Erinn G. Ryen Anne Sherman Rochester Institute of Technology Wells College Think Impact [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT: Business models that lead to reduced consumption of resources and energy and sup- port a Circular Economy can help businesses address the world’s pressing environmental problems. At the same time, they are concepts that have taken decades to garner serious attention in manage- ment literature. -

Sustainable Jet Fuel for Aviation

Sustainable jet fuel for aviation Nordic perpectives on the use of advanced sustainable jet fuel for aviation Sustainable jet fuel for aviation Nordic perpectives on the use of advanced sustainable jet fuel for aviation Erik C. Wormslev, Jakob Louis Pedersen, Christian Eriksen, Rasmus Bugge, Nicolaj Skou, Camilla Tang, Toke Liengaard, Ras- mus Schnoor Hansen, Johannes Momme Eberhardt, Marie Katrine Rasch, Jonas Höglund, Ronja Beijer Englund, Judit Sandquist, Berta Matas Güell, Jens Jacob Kielland Haug, Päivi Luoma, Tiina Pursula and Marika Bröckl TemaNord 2016:538 Sustainable jet fuel for aviation Nordic perpectives on the use of advanced sustainable jet fuel for aviation Erik C. Wormslev, Jakob Louis Pedersen, Christian Eriksen, Rasmus Bugge, Nicolaj Skou, Camilla Tang, Toke Liengaard, Rasmus Schnoor Hansen, Johannes Momme Eberhardt, Marie Katrine Rasch, Jonas Höglund, Ronja Beijer Englund, Judit Sandquist, Berta Matas Güell, Jens Jacob Kielland Haug, Päivi Luoma, Tiina Pursula and Marika Bröckl ISBN 978-92-893-4661-0 (PRINT) ISBN 978-92-893-4662-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-92-893-4663-4 (EPUB) http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/TN2016-538 TemaNord 2016:538 ISSN 0908-6692 © Nordic Council of Ministers 2016 Layout: Hanne Lebech Cover photo: Scanpix Print: Rosendahls-Schultz Grafisk Copies: 100 Printed in Denmark This publication has been published with financial support by the Nordic Council of Ministers. However, the contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views, policies or recom- mendations of the Nordic Council of Ministers. www.norden.org/nordpub Nordic co-operation Nordic co-operation is one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involv- ing Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. -

Unilever Time to Lead Us out of the Plastics Crisis © Greenpeace© © Justin© Hofman Greenpeace

Unilever Time to lead us out of the plastics crisis © Greenpeace© © JustinHofman Greenpeace/ 2 Greenpeace Nederland Unilever Time to lead us out of the plastics crisis The problem with plastics Unilever’s plastic footprint and impact Every year, millions of tonnes of plastic waste is polluting our oceans, A 2019 audit of plastic waste (brand audit) by NGO GAIA reveals waterways and communities and impacting our health. Plastic Unilever as the second worst polluter in terms of collected plastic packaging, designed to be used once and thrown away, is one of pollution in the Philippines,7 and it has featured among the top the biggest contributors to the global plastics waste stream.1 The polluters in several other brand audits recently: Unilever was the vast majority of the 8.3 billion tonnes of plastic that has ever been number 2 polluter in a Manila brand audit in 2017, and number produced has been dumped into landfills or has ended up polluting 7 in a global brand audit in 2018, which represented 239 clean- our rivers, oceans, waterways and communities and impacting our ups spanning 42 countries. Therefore Unilever has both a huge health.2 Every year, between 4.8 to 12.7 million tonnes of plastic responsibility for the plastic pollution crisis, and an opportunity to enter our oceans,3 with only nine percent of plastic waste recycled tackle the problem at the source by reducing its use of single-use globally.4 We don’t know exactly how long oil-based plastic will take plastic packaging units. to break down, but once it’s in the environment, it is impossible to clean up; and so the plastic waste crisis continues. -

The Key Drivers of Born-Sustainable Businesses: Evidence from the Italian Fashion Industry

sustainability Article The Key Drivers of Born-Sustainable Businesses: Evidence from the Italian Fashion Industry Grazia Dicuonzo 1,* , Graziana Galeone 1 , Simona Ranaldo 1 and Mario Turco 2 1 Department of Economics, Management and Business Law, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Largo Abbazia Santa Scolastica, 53, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (G.G.); [email protected] (S.R.) 2 Department of Economic Sciences, University of Salento, Centro Ecotekne Pal. C—S.P. 6 Lecce—Monteroni, 73100 Lecce, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 26 October 2020; Accepted: 3 December 2020; Published: 8 December 2020 Abstract: Environmental pollution has become one of the most pressing preoccupations for governments, policymakers, and consumers. For this reason, many companies make constant efforts to comply with international laws and standards on ethics, social responsibility, and environmental protection. Fashion companies are among the main producers of pollution because their manufacturing processes result in highly negative outcomes for the environment. In recent years, numerous fashion industries have been transforming their production policies to be sustainable, while others are already born as sustainable businesses. Based on Resource-Based View (RBV) theory and Natural Resource-Based View theory (NRBV), this paper aims at understanding how internal and external factors stimulate born-sustainable businesses operating in the fashion sector, adopting a multiple case study methodology. Our analysis shows that culture, entrepreneurial orientation of the founders, and the proximity of the suppliers among the internal factors, combined with the increase of green consumers as an external factor, foster the creation of green businesses. -

The Sustainability Imperative: Business and Investor Outlook

The Sustainability Imperative: Business and Investor Outlook 2018 Bloomberg Sustainable Business & Finance Survey The Sustainability Imperative: Business and Investor Outlook 2018 Bloomberg Sustainable Business & Finance Survey Corporations and the financial institutions that invest in, The challenges and initiatives provide context behind lend to, and insure them, are at a critical juncture for corporate and financial sustainability practices between engagement on sustainability issues. While the the two regions, and a deeper understanding of how sustainability of a company and its financial the relationship between investors and corporations stakeholders have always been interdependent, this might look in the future. bond has reached an inflection point. Survey Criteria and Objectives From the first socially-responsible investment funds in the 1970s to 2000 when the Global Reporting Initiative The survey, completed in July 2018, included 600 launched its first sustainability reporting framework, the respondents, broken down by 400 respondents from interest of financial firms in corporate environmental, the U.S. and 200 from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and social and Governance (ESG) factors continues to rise. the U.K. Each group was split in half, with 200 U.S. corporations, 200 U.S. investors, 100 European The growth of investor networks like the United Nations corporations, and 100 European investors.² Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), which brings together investors with shared beliefs to promote The information gleaned from these survey groups sustainable investment practices, has only deepened provides a better understanding of how corporate adoption of sustainable business and finance. leaders and investors define sustainability, and how it is implemented in business and financial strategies. -

Clarifying the Meaning of Sustainable Business

OAEXXX10.1177/1086026615575176Organization & EnvironmentDyllick and Muff 575176research-article2015 Article Organization & Environment 1 –19 Clarifying the Meaning of © 2015 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: Sustainable Business: Introducing a sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1086026615575176 Typology From Business-as-Usual oae.sagepub.com to True Business Sustainability Thomas Dyllick1 and Katrin Muff2 Abstract While sustainability management is becoming more widespread among major companies, the impact of their activities does not reflect in studies monitoring the state of the planet. What results from this is a “big disconnect.” With this article, we address two main questions: “How can business make an effective contribution to addressing the sustainability challenges we are facing?” and “When is business truly sustainable?” In a time when more and more corporations claim to manage sustainably, we need to distinguish between those companies that contribute effectively to sustainability and those that do not. We provide an answer by clarifying the meaning of business sustainability. We review established approaches and develop a typology of business sustainability with a focus on effective contributions for sustainable development. This typology ranges from Business Sustainability 1.0 (Refined Shareholder Value Management) to Business Sustainability 2.0 (Managing for the Triple Bottom Line) and to Business Sustainability 3.0 (True Sustainability). Keywords business sustainability, corporate sustainability, triple bottom line, planetary challenges, corporate social responsibility, responsible leadership, purpose of the firm, sustainable development, sustainable business Introduction While sustainability management is becoming more widespread among major companies, the impact of their activities is not reflected in studies that monitor the state of the planet. The con- sequence is a “big disconnect” between micro-level progress and macro-level deterioration. -

Key Messages on “How to Design, Implement and Replicate

________________________________________________________________________________ Key messages on “How to design, implement and replicate sustainable small-scale livelihood-oriented bioenergy initiatives, based on the Technical Consultation held in FAO, Rome, 28-29 October 2009 1. Some facts and figures on rural energy situation in developing countries are daunting and show that something has to be done about it. Three billion people rely on unsustainable biomass-based energy resources (UNDP/WHO 2009 1) and 1.6 billion people), mostly rural poor lack access to electricity (IEA 2002 2). This situation entrenches mass scale poverty and perpetuates the unsustainable use of traditional solid biomass (wood, charcoal, agricultural residues and animal waste), in particular for essential cooking and heating energy services. Two million people die every year due to indoor burning of solid fuels in unventilated kitchens . Some 44 percent of these deaths are children; and among adult deaths, 60 percent are women (UNDP/WHO 2009 3) .This makes indoor air pollution the fourth leading cause of premature death in developing countries. National policies and programs aimed at providing broader access to energy services for the rural poor will significantly contribute to sustainable development and achievement of the Millennium Development Goals . This can be significantly supported and partially achieved through the design and implementation of livelihood-oriented, gender sensitive small-scale bioenergy schemes, adapted to local conditions. 1 UNDP/WHO 2009 report, The Energy Access Situation in Developing Countries, A Review Focusing on the Least Developed Countries and Sub-Saharan Africa, http://www.undp.org/energy. 2 IEA 2002. World Energy Outlook. Chapter 13. Energy and Poverty. -

Sustainable Business Models: Time for Innovation

Sustainable Business Models: Time for Innovation By Diane Osgood, Ph.D., Vice President, CSR Strategy, BSR Originally published in the BSR Insight: November 3, 2009 About BSR Imagine that when you buy a pair of jeans you’re offered an agreement to sign A leader in corporate before you pay: “I hereby promise to cold-wash, line-dry this clothing item, and responsibility since 1992, own it for at least three years or ensure it is given away for someone else to BSR works with its global enjoy.” When you sign, you are rewarded instantly with a coupon for cash back. network of more than 250 The rebate is the estimated financial value of the carbon-dioxide emissions you member companies to save by avoiding hot-water washing, and by machine drying your jeans over the develop sustainable business lifespan of the item. The clothing company is able to provide this discount by strategies and solutions aggregating its consumers’ carbon credits and selling them on the open market. through consulting, research, This model provides financial incentives for both the clothing company and the and cross-sector collab- consumer to alter behavior. oration. With six offices in Asia, Europe, and North Far from fail-proof, this scenario is not yet being played out in any store near you. America, BSR uses its But some version is not far off, as pioneering companies pilot innovative expertise in the environment, approaches to survive and thrive in a more sustainable economy. human rights, economic development, and govern- Today, business leaders face not only the economic fallout of the financial crisis, ance and accountability to they face the substantial challenge of transitioning to a low-carbon economy that guide global companies is constrained by dwindling natural resources. -

Corporate Environmentalism: How Green Is It Actually? Emma Rotner Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Environmental Studies Honors Papers Environmental Studies Program 2016 Corporate Environmentalism: How Green is it Actually? Emma Rotner Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/envirohp Part of the Environmental Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rotner, Emma, "Corporate Environmentalism: How Green is it Actually?" (2016). Environmental Studies Honors Papers. 14. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/envirohp/14 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Studies Program at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Studies Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Corporate Environmentalism: How Green is it Actually? Presented By: Emma L. Rotner To the Department of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Environmental Studies Advisor, Jane Dawson Second Reader, Maria Cruz-Saco Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 5th, 2016 Acknowledgments A special thanks to my advisor, Jane Dawson, for her constant support and guidance throughout this process, and for fueling my passion of environmental justice, beginning when I was a freshman in her introductory environmental studies class. Thank you to Maria-Cruz Saco for taking the time to be my second reader. I would also like to thank the Goodwin-Niering Center for the Environment for making my research possible, for bringing me together with a group of like-minded and passionate individuals, and for encouraging me to take risks in order to make a difference in the world. -

An Introduction to Sustainable Business

An Introduction to Sustainable Business v. 1.0 This is the book An Introduction to Sustainable Business (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This book was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. ii Table of Contents Dedication............................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgments................................................................................................................. 2 -

Environmental Sustainability in Business

Environmental Sustainability in Business A guide to help you make responsible decisions that will reduce your business' negative impact on the environment Environmental sustainability involves making decisions and taking action that are in the interests of protecting the natural world. In this guide, you will find information about using environmentally sustainable business practices to gain a competitive advantage in the market. © State of New South Wales through NSW Trade & Investment Environmental Sustainability in Business This guide looks at ways to reduce your business' negative impact on the environment. and covers the following content: 1. What is Environmental Sustainability? ................................................................. 3 2. Business Case for Environmental Sustainability ................................................ 4 3. Consumer Conscience and Public Image .............................................................. 6 4. Business Differentiation ............................................................................................ 7 5. Environmental Marketing .......................................................................................... 9 2 1. What is Environmental Sustainability? Environmental sustainability involves making decisions and taking action that are in the interests of protecting the natural world, with particular emphasis on preserving “There is a the capability of the environment to support human life. It is an important topic at the present time, as people are realising -

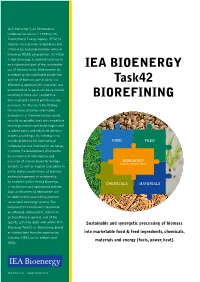

IEA Bioenergy Task42 Biorefining Deals with Knowledge Building and Exchange Within the Area of Biorefining, I.E

IEA Bioenergy is an international collaboration set-up in 1978 by the International Energy Agency (IEA) to improve international co-operation and information exchange between national bioenergy RD&D programmes. Its Vision is that bioenergy is, and will continue to be a substantial part of the sustainable IEA BIOENERGY use of biomass in the BioEconomy. By accelerating the sustainable production and use of biomass, particularly in a Task42 Biorefining approach, the economic and environmental impacts will be optimised, resulting in more cost-competitive BIOREFINING bioenergy and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Its Mission is facilitating the commercialisation and market deployment of environmentally sound, socially acceptable, and cost-competitive bioenergy systems and technologies, and to advise policy and industrial decision makers accordingly. Its Strategy is to provide platforms for international FOOD FEED collaboration and information exchange, including the development of networks, dissemination of information, and provision of science-based technology BIOENERGY (FUELS, POWER, HEAT) analysis, as well as support and advice to policy makers, involvement of industry, and encouragement of membership by countries with a strong bioenergy CHEMICALS MATERIALS infrastructure and appropriate policies. Gaps and barriers to deployment will be addressed to successfully promote sustainable bioenergy systems. The purpose of this brochure is to provide an unbiased, authoritative statement on biorefining in general, and of the specific activities