A Brief Discussion of Principles of Candy Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Candy Making Made Easy (Because It Is)

05_597345 ch01.qxd 7/29/05 7:08 PM Page 9 Chapter 1 Candy Making Made Easy (Because It Is) Recipes in In This Chapter This Chapter ᮣ Gearing up to make candy ᮣ Dream Dates ᮣ Identifying some great confections ᮣ Checking out special uses for your candy-making skills ne point I stress throughout this book is that candy making is pretty Oeasy. After you learn a few basics and prepare yourself and your envi- ronment according to my simple guidelines, all you have to do is follow a few procedures. I hate to say this, but if I can make candy, you can make candy. When I train new staff members in my candy shop, I observe that, at first, they’re hesitant and overly careful about handling the product, as if it were very fragile. I assure them that they will not hurt the candy by being aggres- sive. I don’t want them to be afraid of the candy, and you shouldn’t be afraid, either. Most products you make are quite tolerant, and you can stir them hard, slap them, or just generally be rough with them. Don’t be afraid to get your hands a little messy, and don’t worry about making a bit of a mess. Have fun, because you’re in charge. To make a point, when someone observes that I have a spot of chocolate on my face, I dab even more on and ask, “Where, here?” Then I touch another spot withCOPYRIGHTED a big dab and ask, “Or was it here?” MATERIAL Before I finish, I have chocolate all over my face, but the new person is relaxed, confident that I am crazy and not worried about making a mess. -

Candy Making Secrets

C a n dy M a ki n g S e cr e t s by MARTIN A . PEASE In which y ou ar e taught to d uplicate AT H OME n ca the fi est ndies m ad e b y any one . C ontaining r ecipes never published r in this fo m b efore. Published by PEASE AND DENISON N ILLI O I ELGl , N S EM RY Of CO NGH QS S Um Games:ti ecesvaci MAY 23 1 908 Gawa i n ; u m : 2 3 f ee 3 CO PY RIGH T , 1908 . PEASE AND DENISON Th e News - Ad vocate n I in i Elgi , ll o s To My WIFE AND BABIES whose fondness of candy led m e to m ake such a success of Hom e Ca ndy M ak n th b k is i g , is oo RESPE CTFULL Y DEDI CA TED By the A uthor INTRODUCTION I I ns N G V N G you the recipes and i tructions contained herein , I have done wh at ~ n o other candym aker ever did to my w a kno ledge , as they always refuse to teach nyone to make candy at home . e m e Aft r teaching a few ladies , the incessant demands on for lessons led me to the writing of this book . It is diff erent from mo st oth er books on H ome Candy M — aking , as I teach you the same method as used by the finest s confectioners , with use of a thermometer , which enable you to always make your candy the same . -

![IS 1008 (2004): Sugar Boiled Confectionery [FAD 16: Foodgrains, Starches and Ready to Eat Foods]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6226/is-1008-2004-sugar-boiled-confectionery-fad-16-foodgrains-starches-and-ready-to-eat-foods-226226.webp)

IS 1008 (2004): Sugar Boiled Confectionery [FAD 16: Foodgrains, Starches and Ready to Eat Foods]

इंटरनेट मानक Disclosure to Promote the Right To Information Whereas the Parliament of India has set out to provide a practical regime of right to information for citizens to secure access to information under the control of public authorities, in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority, and whereas the attached publication of the Bureau of Indian Standards is of particular interest to the public, particularly disadvantaged communities and those engaged in the pursuit of education and knowledge, the attached public safety standard is made available to promote the timely dissemination of this information in an accurate manner to the public. “जान का अधकार, जी का अधकार” “परा को छोड न 5 तरफ” Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan Jawaharlal Nehru “The Right to Information, The Right to Live” “Step Out From the Old to the New” IS 1008 (2004): Sugar Boiled Confectionery [FAD 16: Foodgrains, Starches and Ready to Eat Foods] “ान $ एक न भारत का नमण” Satyanarayan Gangaram Pitroda “Invent a New India Using Knowledge” “ान एक ऐसा खजाना > जो कभी चराया नह जा सकताह ै”ै Bhartṛhari—Nītiśatakam “Knowledge is such a treasure which cannot be stolen” IS 1008: 2004 Reaffirmed 2009 ~1fR(1i TIS 1008: 2004 \3~J) st ~ Ch't ch't'"icflCf~r;ffi - ~ (~Fftwr ) Indian Standard SUGAR BOILED CONFECTIONERY SPECIFICATION ( Second Revision) ICS 67.060 ©BIS 2004 BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS MANAK BHA VAN, 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI 110002 October 2004 Price Group 2 AMENDMENT NO. 1 FEBRUARY 2006 TO IS 1008: 2004 SUGAR BOILED CONFECTIONERY SPECIFICATION ( Second Revision) ( First cover, second cover and page 1 ) - Substitute 'Thud Revision' for 'Second Revision' and wherever it appears. -

5Lb. Assortment

Also available in Red 5LB. ASSORTMENT Pecan or Almond Törtél Caramel Pilgrim Hat Our slightly chewy caramel Creamy, extra soft caramel covering roasted pecans or in dark chocolate. almonds. Milk or dark chocolate. English Toffee Irish Toffee Chewy, ”melt-in-your-mouth” Baton-shaped, buttery toffee. toffee, dipped in milk chocolate. The Irish is brittle and crunchy. Dipped in milk or dark chocolate. Hazelnut Toffee Buttery brittle toffee with roasted Good News Mint Caramel chopped hazelnuts. Dipped in Creamy mint caramel dipped milk or dark and sprinkled with in milk chocolate only. caramelized hazelnuts. ASSORTMENT 5 LB. (108 PC.) - ASSORTMENT In response to our customers request, we have created an extra large assortment! This includes: Soft a’ Silk Caramel, Hazelnut Toffee, Solid Belgian Chocolate, Peanut Butter Smooth and Crunch, Pecan and Almond Törtéls, Caramel Pilgrim Hats, Good News Mint Caramel, Irish and English Toffees, Hazelnut Praline, as well as, Salty Brits, Coconut Igloos, Marzipan and Cherry Hearts. Packaged in one of our largest hinged box and includes our wired gift bow. $196.75 (108 pc.) Toll Free: 800-888-8742 | Local: 203-775-2286 1 Fax: 203-775-9369 | [email protected] Almond Toffee Peanut Butter Pattie Brittle and crunchy with roasted Our own smooth peanut butter almonds. Milk or dark chocolate. shaped into round patties. Dipped in milk chocolate. Hazelnut Praline Hazelnut praline (Gianduja) is Solid Belgian Chocolate ASSORTMENT THE BRIDGEWATER made from finely crushed filberts Our blend of either dark or milk mixed with milk chocolate. Dipped chocolate. in milk or dark. Peanut Butter Crunch Our own creamy peanut butter Soft a’ Silk Caramel with the addition of chopped Soft and creamy caramel dipped caramelized nuts. -

Candy Making Secrets

C a n dy M a ki n g S e cr e t s by MARTIN A . PEASE In which y ou ar e taught to d uplicate AT H OME n ca the fi est ndies m ad e b y any one . C ontaining r ecipes never published r in this fo m b efore. Published by PEASE AND DENISON N ILLI O I ELGl , N S EM RY Of CO NGH QS S Um Games:ti ecesvaci MAY 23 1 908 Gawa i n ; u m : 2 3 f ee 3 CO PY RIGH T , 1908 . PEASE AND DENISON Th e News - Ad vocate n I in i Elgi , ll o s To My WIFE AND BABIES whose fondness of candy led m e to m ake such a success of Hom e Ca ndy M ak n th b k is i g , is oo RESPE CTFULL Y DEDI CA TED By the A uthor INTRODUCTION I I ns N G V N G you the recipes and i tructions contained herein , I have done wh at ~ n o other candym aker ever did to my w a kno ledge , as they always refuse to teach nyone to make candy at home . e m e Aft r teaching a few ladies , the incessant demands on for lessons led me to the writing of this book . It is diff erent from mo st oth er books on H ome Candy M — aking , as I teach you the same method as used by the finest s confectioners , with use of a thermometer , which enable you to always make your candy the same . -

LOLLIPOPS 2014, 1997 by David A

LOLLIPOPS 2014, 1997 by David A. Katz. All rights reserved. Reproduction permitted for education use provided original copyright is included. Materials Needed ½ cup light Karo syrup (corn syrup) 1 cup sugar ½ cup water citric acid (only a “pinch” is needed) flavoring (concentrated candy flavoring preferred – 1/8 teaspoon is needed) food color (concentrated candy food colors preferred – add dropwise) lollipop sticks (available in craft stores) lollipop molds (for hard candies) or baking sheets non-stick cooking spray (Pam or equivalent) stirrer (wood spoon or high temperature candy spoon) 600-mL beaker burner and ring stand or hot plate beaker tongs thermometer (250C or candy thermometer) measuring cups and spoons Safety Safety glasses or goggles must be worn in the laboratory at all times. If this experiment is performed in a chemistry laboratory, all work surfaces must be cleaned and free from laboratory chemicals. After cleaning work surfaces, it is advised to cover all work areas with aluminum foil or a food-grade paper covering. All glassware and apparatus must be clean and free from laboratory chemicals. Use only special glassware and equipment, stored away from all sources of laboratory chemical contamination, and reserved only for food experiments is recommended. There are no safety hazards associated with the materials used in this experiment. Disposal Generally, all waste materials in this experiment can be disposed in the trash or poured down the drain with running water. All disposal must conform to local regulations. Procedure Measure 1 cup sugar into a 600-mL beaker. Add 1/2 cup light Karo syrup. Add 1/2 cup water. -

Toffee-Tastic™ Cookie Cake Pops

Toffee-tastic™ Cookie Cake Pops Toffee-tastic™ Cookie Cake Pops INGREDIENTS: 1 box of Toffee-tastic™ Girl Scout Cookies® Cake Pops (made with frosting) • ½ cup+ frosting (Canned or cream cheese frosting) DIRECTIONS: • 1 pkg Toffee-tastic Girl Scout Cookies®, finely chopped 1. Blend together the cookie crumbs and the cream cheese (or frosting) until it can form a ball, adding a little extra cream cheese • ¼ cup toffee bits (or frosting), if needed. A food processor works well for this. • 1 cup coating, melted (chocolate chips, butterscotch 2. Form dough into balls (1-1 ½" size). Refrigerate for 30-60 chips, white chocolate chips minutes. or candy melts) 3. Melt coating in a narrow, tall microwave safe mug. (Start with 30 • Toppings, to decorate tops (toffee bits, chopped pecans, seconds in the microwave, stir, and then continue to microwave colored sprinkles or candies) in additional 10 second intervals until smooth). Do not overheat. • Lollipop sticks 4. Dip the end of your lollipop stick in the melted coating. Insert stick into ball (or if making cookie balls, without sticks, use two Cream Cheese Frosting knifes to lower balls into coating). • 1½ oz cream cheese 5. Dip each ball into the coating until covered, allowing excess to • 2 Tbsp butter drip off into mug. • 1 cup powdered sugar 6. Sprinkle top with toffee, nuts or sprinkles, and allow to cool. • ½ tsp vanilla Beat all ingredients together until smooth. (Yields approximately 3/4 cup) Cookie Balls (made with cream cheese) • 3-4 oz cream cheese By using gluten-free ingredients for these recipes, cookie lovers • 1 pkg Toffee-tastic Girl Scout Cookies®, avoiding gluten can enjoy them, too! finely chopped Either version can be finished out in a candy format, or can • ¼ cup toffee bits be served on a stick, like a cake pop. -

Science Experiment at Home Mezzo 3

Science experiment at home Mezzo 3 How to Make Rock Candy Learn to make rock candy for an edible activity! Making rock candy is also part science experiment, allowing your kid hands-on learning with a few simple ingredients and kitchen tools. This easy rock candy recipe lets your kid observe the crystallization process firsthand while making some pretty delicious treats. Sugar, water, and few more items found at home are all you need. Step 1 How to Make Rock Candy Gather your ingredients and tools. All you need is water, sugar, a clothespin, a pot for boiling, and a few wooden sticks to grow rock candy crystals in your kitchen! You might pick out a food color dye, too. For the "sticks," you can pick up a few bamboo skewers from the grocery store. A few simple ingredients allow you to make rock candy at home. Step 2 Bring two cups of water to a boil in a large pot on the stove. Next, stir in four cups of sugar. Boil and continue stirring until sugar appears dissolved. This creates a supersaturated sugar solution. This is also the time to add in any flavor enhancements, such as vanilla or peppermint and so on. Allow the solution to cool for 15-20 minutes. Create your sugar solution. Step 3 While waiting for the solution to cool, prepare your wooden sticks for growing the rock crystals. Wet the wooden sticks and roll them around in granulated sugar. Make sure you allow the sugared sticks to completely dry before continuing to Step 4. -

Have You Ever Tasted Rock Candy?

ROCK CANDY MADE FROM SUGAR, NOT ROCKS! Have you ever tasted rock candy? What did it taste like? How did it feel? It’s definitely a candy that offers some interesting sensations, both rough in texture and very sweet as it dissolves on your tongue. You can make rock candy at home and learn a bit of science at the same time, though it does require patience. You’ll start to see changes within the first few hours, but it might take up to a week for the rock candy to form. It’s important to have an adult help you with this project because you will be working with a hot liquid. Please be careful! Here is what you will need: • sugar (about 1 cup for each stick of candy, plus extra for dipping - the exact amount depends on the size of jars you're using and how many rock candy sticks you want to make) • water • tall, narrow glass jars (canning jars or something similar) • powdered, flavored drink mix(es) or food colorings and food flavorings • wooden candy sticks, wooden skewers or wooden chopsticks • parchment paper, waxed paper or paper towels • clothespins (for as many jars as you are using) or masking tape to hold sticks in place Clean the glass jars and wooden sticks and set them aside. Have your adult boil some water in a heavy saucepan, calculating about ½ cup of water to every cup of sugar for each candy stick you want to make. For example, if you want to make 4 sticks, then boil 2 cups of water and have 4 cups of sugar handy. -

West Virginia Maple Syrup Producers Association Newsletter

West Virginia Maple Syrup Producers Association Newsletter A Message From Our President July 2017 Dear Members, I would like to begin by thanking Ed Inside This Issue Howell, Mark Bowers and Cathy Hervey for their A Message from Our President..1 service on the executive committee over the past WVMSPA Logo … 2 year and the many people who volunteered their See You at The Fair … 2 time for committee service. I appreciate your 2017 – A Maple Season we will efforts to promote and strengthen our growing association. Never Forget … 2 The 2017 syrup season was another trying season for most of our Dr. Abby’s Workshop … 3 members as we dealt with yet another unusually warm winter and spring. Some Backyard Boling … 3-7 of you may even be thinking “what are we doing, why are we doing this?” As an To Inspect or Not to Inspect? old friend of mine often says… “That’s farming!” We can’t control the weather, That is the Question … 7 but we can control our preparation, quality control, and the many small details Sugar Camp Feature – Blue that go into producing a high quality product like West Virginia Maple Syrup. Even with the 2017 weather we were able to produce over 9,000 gallons of Rock Farm … 8-9 NASS Survey 2017 ….9 finished syrup, 33% more than producers reported for the 2016 season. Turning Your Yellow Leaf The United States, as a whole, added 6% more taps in 2017 versus 2016. Red...10 Our great state of West Virginia added 16% more taps this year, which is the Maple Confections 101 & highest percentage of any state that participated in the USDA National Maple 201...11 Survey. -

22. Role of Ingredients Used in Confectionery Industry 1

Paper No.: 09 Paper Title: BAKERY AND CONFECTIONERY TECHNOLOGY Module – 22: Role of Ingredients used in Confectionery Industry Paper Coordinator: Dr. P. Narender Raju, Scientist, ICAR-NDRI, Karnal Content Writer: Mr. Borad Sanket, Research Scholar, ICAR-NDRI, Karnal 22. Role of Ingredients used in Confectionery industry 1. Sugar • Principal ingredient for all the confection – Sucrose • Non reducing disaccharide, consists of dextrose & fructose • Solubility of 66% at room temperature and 83% under boiling condition • Prepared either from cane sugar or beet sugar commercially • Available in numbers of forms depending on its particle size. • Granulated, milled/icing, coarse, powdered, ultra fine, caster, non-pareil, fine sugar, etc. • Sugar syrups - can be used but stability against microbial spoilage and economy in transportation - hinder their uses Sugar confectionery → Boiled Toffee/ Gums/ Chewing Liquorice sweets Fudge Pastilles Gum Type of Sugar ↓ White granulated Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Specially white granulated Yes Yes Yes No Yes Screened specialities Yes Yes Yes No No Milled specialities Yes Yes No Yes No Brown sugar No Yes No No Yes Liquid sugar Yes Yes Yes No No Syrups and treacles No Yes No No Yes 2. Invert sugar • Invert sugar - available as syrup only • Can be prepared at concentrations as high as 80% at ambient condition • Sufficiently low water activity capable of restricting microbial proliferation • Can be mixed easily with sucrose • Can be concentrated sufficiently to yield products with sufficiently low water activity without -

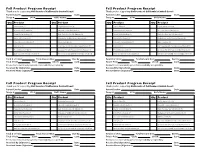

Fall Product Program Receipt Fall Product Program Receipt Fall

Fall Product Program Receipt Fall Product Program Receipt Thank you for supporting Girl Scouts of California’s Central Coast! Thank you for supporting Girl Scouts of California’s Central Coast! Parent/Leader: Date: Parent/Leader: Date: Troop #: SU #: Girl’s Name: Troop #: SU #: Girl’s Name: Qty Product Qty Product Qty Product Qty Product Care to Share $6 English Butter Toffee $8 Care to Share $6 English Butter Toffee $8 Honey Roasted Peanuts $6 Chocolate Covered Almonds $9 Honey Roasted Peanuts $6 Chocolate Covered Almonds $9 Peanut Butter Monkeys $6 Dark Chocolate Sea Salt Almonds $9 Peanut Butter Monkeys $6 Dark Chocolate Sea Salt Almonds $9 Butter Toffee Peanuts $7 Madagascar Vanilla & Honey Almonds $10 Butter Toffee Peanuts $7 Madagascar Vanilla & Honey Almonds $10 Chocolate Covered Raisins $7 Whole Cashews $10 Chocolate Covered Raisins $7 Whole Cashews $10 Fruit Slices $7 City Scape Tin with Chocolate Covered Pretzels $11 Fruit Slices $7 City Scape Tin with Chocolate Covered Pretzels $11 Honey BBQ Snack Mix $7 Snowman Tin with Peppermint Bark Rounds $11 Honey BBQ Snack Mix $7 Snowman Tin with Peppermint Bark Rounds $11 Dark Chocolate Sea Salt Caramels $8 Girl Scout Tin with Milk Chocolate Mint Trefoils $11 Dark Chocolate Sea Salt Caramels $8 Girl Scout Tin with Milk Chocolate Mint Trefoils $11 Total # of Units: Total Amount Due: Due By: Total # of Units: Total Amount Due: Due By: Total $ Paid: Cash: Check: Card: Total $ Paid: Cash: Check: Card: Products received and payment responsibility accepted by: Products received and payment