An Unrighteous Piece of Business: a New Institutional Analysis of the Memphis Riot of 1866

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20Th Running UNOH "175" - NASCAR Camping World Truck Series - New Hampshire Motor Speedway - 9/23/2017 Last Update: 9/20/2017 11:26:00 AM

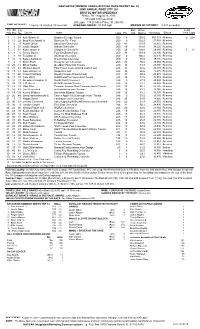

20th Running UNOH "175" - NASCAR Camping World Truck Series - New Hampshire Motor Speedway - 9/23/2017 Last Update: 9/20/2017 11:26:00 AM Entry Veh # Driver Owner Crew Chief Veh Mfg Sponsor 1 0 Ray Ciccarelli Jennifer Jo Cobb Daniel Sowers Jr 15 Chevrolet Star Sales Silverado 2 1 Jordan Anderson Tracy Lowe Ryan Fields 16 Chevrolet Lucas Oil/Bommarito.com 3 02 Austin Hill Randy Young Matt Petrea 16 Ford TBD 4 4 Christopher Bell Kyle Busch Ryan Fugle 17 Toyota TBD 5 006 Norm Benning Norm Benning Dan Sheffer 17 Chevrolet TBD 6 8 John Hunter Nemechek Joe Nemechek Gere Kennon Jr 17 Chevrolet Fire Alarm Services. 7 110 Jennifer Jo Cobb Jennifer Jo Cobb Timmy Sliva 15 Chevrolet TBD 8 13 Cody Coughlin Duke Thorson Michael Shelton 17 Toyota JEGS 9 15 Gray Gaulding(i) Jay Robinson Scott Eggleston 17 Chevrolet TBD 10 16 Ryan Truex Shigeaki Hattori Scott Zipadelli 17 Toyota Price Chopper 11 18 Noah Gragson Kyle Busch Marcus Richmond II 17 Toyota Switch 12 19 Austin Cindric Brad Keselowski Doug Randolph 17 Ford Draw-Tite / Reese Brands 13 21 Johnny Sauter Maurice Gallagher Jr Joe Shear Jr 17 Chevrolet TBD 14 124 Justin Haley Maurice Gallagher Jr Kevin Bellicourt 17 Chevrolet Fraternal Order of Eagles 15 27 Ben Rhodes Duke Thorson Eddie Troconis 17 Toyota Safelite Auto Glass 16 29 Chase Briscoe Brad Keselowski Mike Hillman Jr 17 Ford Cooper Standard 17 33 Kaz Grala Maurice Gallagher Jr Jerry Baxter 17 Chevrolet TBD 18 44 Austin Self Shane Lamb Kevin Eagle 17 Chevrolet AM Technical Solutions 19 145 T J Bell Al Niece Cody Efaw 17 Chevrolet Niece Equipment -

Official Race Results

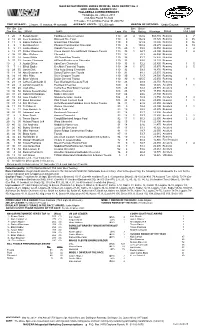

NASCAR NATIONWIDE SERIES OFFICIAL RACE REPORT No. 8 22ND ANNUAL AARON'S 312 TALLADEGA SUPERSPEEDWAY Talladega, AL - May 4, 2013 2.66-Mile Paved Tri-Oval 117 Laps - 311.22 Miles Purse: $1,200,772 TIME OF RACE: 2 hours, 11 minutes, 44 seconds AVERAGE SPEED: 133.269 mph MARGIN OF VICTORY: Under Caution Fin Str Car Bns Driver Lead Pos Pos No Driver Team Laps Pts Pts Rating Winnings Status Tms Laps 1 20 7 Regan Smith TaxSlayer.com Chevrolet 110 47 4 112.6 $53,445 Running 6 7 2 12 22 Joey Logano (i) Discount Tire Ford 110 0 132.9 39,725 Running 9 35 3 11 5 Kasey Kahne (i) Great Clips Chevrolet 110 0 121.9 30,500 Running 9 16 4 9 1 Kurt Busch (i) Phoenix Construction Chevrolet 110 0 103.2 29,275 Running 5 19 5 5 31 Justin Allgaier Brandt Chevrolet 110 40 1 99.5 34,550 Running 2 4 6 18 77 Parker Kligerman Camp Horsin' Around/Bandit Chippers Toyota 110 39 1 94.7 28,100 Running 3 4 7 38 01 Mike Wallace Chevrolet 110 37 70.3 26,500 Running 8 31 24 Jason White JW Demolition Toyota 110 36 61.7 25,850 Running 9 37 51 Jeremy Clements AllSouthElectric.com Chevrolet 110 35 69.0 25,225 Running 10 2 3 Austin Dillon AdvoCare Chevrolet 110 35 1 72.2 26,825 Running 1 5 11 7 11 Elliott Sadler OneMain Financial Toyota 110 34 1 97.5 25,975 Running 3 5 12 29 55 Jamie Dick Viva Auto Group Chevrolet 110 32 59.3 18,850 Running 13 14 99 Alex Bowman # SchoolTipline.com Toyota 110 31 88.1 25,675 Running 14 24 19 Mike Bliss Dixie Chopper Toyota 110 30 73.7 24,500 Running 15 21 20 Brian Vickers Dollar General Toyota 110 30 1 105.5 25,050 Running 1 1 16 27 79 Jeffrey Earnhardt -

Texas Motor Speedway - 6/10/2016 Last Update: 6/6/2016 4:15:00 PM

20th Annual Rattlesnake "400" - NASCAR Camping World Truck Series - Texas Motor Speedway - 6/10/2016 Last Update: 6/6/2016 4:15:00 PM Entry Veh # Driver Owner Crew Chief Veh Mfg Sponsor 1 00 Cole Custer Dale Earnhardt Jr David McCarty 16 Chevrolet Haas Automation 2 1 TBA Tracy Lowe Daniel Sowers Jr 16 Chevrolet TBA 3 02 Tyler Young Randy Young Andrew Abbott 16 Chevrolet Randco 4 4 Christopher Bell Kyle Busch Jerry Baxter 16 Toyota JBL 5 05 John Wes Townley Tony Townley James Villeneuve 16 Chevrolet Jive Communications / Zaxbys 6 6 Norm Benning Norm Benning Brian Poff 16 Chevrolet TBD 7 07 Ryan Lynch Bobby Dotter Ken Evans 16 Chevrolet BlankHood.com 8 8 John Hunter Nemechek Joe Nemechek Gere Kennon Jr 16 Chevrolet Fire Alarm Services, Inc 9 9 William Byron Kyle Busch Ryan Fugle 16 Toyota Liberty University 10 10 Jennifer Jo Cobb Jennifer Jo Cobb Steve Kuykendall 15 Chevrolet Grimes Irrigation & Construction 11 11 German Quiroga Tom Deloach Scott Zipadelli 16 Toyota TBA 12 13 Cameron Hayley Duke Thorson Eddie Troconis 16 Toyota Cabinets by Hayley 13 17 Timothy Peters Tom Deloach Shane Huffman 16 Toyota Red Horse Racing 14 19 Daniel Hemric Brad Keselowski Chad Kendrick 15 Ford DrawTite 15 20 Austin Hill Bryan Hill Doug Chouinard 13 Ford A + D Welding, Inc 16 21 Johnny Sauter Maurice Gallagher Jr Joe Shear Jr 16 Chevrolet Smokey Mountain Herbal Snuff 17 22 Austin Self Tim Self Marc Browning 16 Toyota AM Technical Solutions 18 23 Spencer Gallagher Maurice Gallagher Jr Jeff Hensley 16 Chevrolet Allegiant Travel 19 29 Tyler Reddick Brad Keselowski -

NASCAR K&N Pro Series East United Site Services 70 Saturday, July 21

NASCAR K&N Pro Series East United Site Services 70 Saturday, July 21, 2018 at 6:45 p.m. Entry List by Car Number Car # Driver Owner Car Crew Chief Sponsor 1 2 Ryan Vargas Max Siegel Toyota Matt Bucher NASCAR Technical Institute 2 04 Ronnie Bassett Jr. Ronnie Bassett Sr. Chevrolet Daniel Johnson Bassett Gutters and More Inc. 3 6 Ruben Garcia Jr. Max Siegel Toyota Steve Plattenberger Max Siegel Inc. 4 12 Harrison Burton Matthew Miller Toyota Shane Huffman Dex Imaging 5 14 Trey Hutchens Bobby Hutchens Jr. Chevrolet Bobby Hutchens Jr. Autozone 6 15 Chase Cabre Max Siegel Toyota Tyler Green E3 Spark Plug 7 16 Derek Kraus Mike Curb Toyota John Camilleri NAPA Auto Parts/Curb Records 8 17 Tyler Ankrum David Gilliland Toyota Seth Smith Modern Meat Company 9 18 Colin Garrett Sam Hunt Toyota Clinton Cram Propel GPS 10 19 Hailie Deegan Bill McAnally Toyota Ty Joiner Mobil 1/NAPA Power Premium Plus 11 27 Sam Mayer Jerry Pitts Ford Jerry Pitts Titan 12 30 Tristan Van Wieringen Mark Rette Ford Mark Rette DuroByte 13 40 Anthony Alfredo Mark McFarland Toyota Robert Huffman Ceco Building Systems 14 44 Dillon Bassett Ronnie Bassett Sr. Chevrolet Skip Eyler Bassett Gutters and More Inc. 15 54 Tyler Dippel David Gilliland Toyota Chris Lawson TyCar Trenchless Technologies/D&A Concrete 16 55 Abraham Calderon Carlos Crespo Chevrolet TBA EJP Racing 17 59 Reid Lanpher Carlos Crespo Chevrolet Jeff Jefferson EJP Racing 18 71 Bill Hoff JP Morgan Chevrolet TBA Mawson & Mawson 19 74 Brandon McReynolds Marie Benevento-Visconti Chevrolet Bruce Cook IGA/The Reichert Group 20 82 Spencer Davis Danny Watts Jr. -

12-08-HR Haldeman

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Contested Materials Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 12 8 7/21/1971Domestic Policy Memo From Deborah Sloan to Henry Cashen. RE: List of celebrities invited to the White House during the Nixon Administration. 14 pgs. 12 8 10/25/1971Domestic Policy Memo From Gordon Strachan to Haldeman. RE: Campaign strategy to utilize celebrities to help Nixon attain re-election on November 7, 1972. 1 pg. 12 8 10/20/1971Domestic Policy Memo From Haldeman to Fred Malek. RE: A scheduled meeting between the Attorney General and a group of entertainment industry leaders, in order to attain the names of celebrities who will be helpful in the campaign. 1 pg. 12 8 10/18/1971Domestic Policy Memo From Jeb Magruder to the Attorney General. RE: The use of celebrities as a means to maximize support for Nixon's campaign. 3 pgs. Monday, December 13, 2010 Page 1 of 7 Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 12 8 10/12/1971Economy Memo From Charles Colson to Haldeman. RE: The limitations faced by the Nixon Administration concerning the aid of celebrities, and the solution being "active recruiting by a leading celebrity." 1 pg. 12 8 10/11/1971Domestic Policy Memo From Henry Cashen II to Charles Colson. RE: Progress made in attaining celebrity endorsements such as athletes; however, a lack of White House functions has limited actors and entertainers from participating. 3 pgs. 12 8 8/12/1971Domestic Policy Memo From Henry Cashen II to Donald Rumsfeld. -

Martinsville Speedway - 4/1/2017 Last Update: 3/30/2017 2:55:00 PM

19th Annual Alpha Energy Solutions "250" - NASCAR Camping World Truck Series - Martinsville Speedway - 4/1/2017 Last Update: 3/30/2017 2:55:00 PM Entry Veh # Driver Owner Crew Chief Veh Mfg Sponsor 1 1 Bryce Napier Tracy Lowe Mike Harmon 16 Chevrolet ASAP Appliance Service 2 02 Austin Hill Randy Young Bruce Cook 16 Ford Victory Wear 3 4 Christopher Bell Kyle Busch Ryan Fugle 17 Toyota JBL 4 * 5 Korbin Forrister Richard Wauters Richard Wauters 17 Toyota TBD 5 6 Norm Benning Norm Benning Christopher Aunspaw 17 Chevrolet Houston Roll Pipe / Diamond G Inspection 6 7 Brett Moffitt Tom Deloach Butch Hylton 17 Toyota TBD 7 8 John Hunter Nemechek Joe Nemechek Gere Kennon Jr 17 Chevrolet D.A.B. Constructors, Inc. 8 10 Charles Buchanan Jr Jennifer Jo Cobb Craig Wood 15 Ford Spring Drug 9 12 Jordan Anderson Rick Ware Cody Ware 12 Chevrolet Lucas Oil 10 13 Cody Coughlin Duke Thorson Michael Shelton 17 Toyota JEGS 11 16 Ryan Truex Shigeaki Hattori Scott Zipadelli 17 Toyota Harris Teeter \ Bar Harbor 12 17 Timothy Peters Tom Deloach Chad Kendrick 17 Toyota TBD 13 18 Noah Gragson Kyle Busch Marcus Richmond II 17 Toyota Switch 14 19 Austin Cindric Brad Keselowski Doug Randolph 15 Ford LTi Printing 15 21 Johnny Sauter Maurice Gallagher Jr Joe Shear Jr 17 Chevrolet Allegiant Travel 16 22 Austin Self Tim Self Rick Ren II 17 Toyota Go Texan\AM Technical Solutions 17 23 Chase Elliott(i) Maurice Gallagher Jr Joey Cohen 17 Chevrolet Allegiant Airlines / NAPA 18 24 Justin Haley Maurice Gallagher Jr Kevin Bellicourt 17 Chevrolet AccuDoc Solutions 19 27 Ben Rhodes -

Lead Fin Pos Driver Team Laps Pts Bns Pts Winnings Status Tms Laps Str Pos Car No Driver Rating 1 1 54 Kyle Busch

NASCAR NATIONWIDE SERIES OFFICIAL RACE REPORT No. 23 32ND ANNUAL FOOD CITY 250 BRISTOL MOTOR SPEEDWAY Bristol, TN - August 23, 2013 .533-Mile Concrete Oval 250 Laps - 133.25 Miles Purse: $1,238,835 TIME OF RACE: 1 hours, 26 minutes, 55 seconds AVERAGE SPEED: 91.985 mph MARGIN OF VICTORY: 0.831 second(s) Fin Str Car Bns Driver Lead Pos Pos No Driver Team Laps Pts Pts Rating Winnings Status Tms Laps 1 1 54 Kyle Busch (i) Monster Energy Toyota 250 0 150.0 $53,315 Running 2 228 2 15 22 Brad Keselowski (i) Discount Tire Ford 250 0 122.2 37,650 Running 3 6 3 Austin Dillon AdvoCare Chevrolet 250 41 113.9 36,975 Running 4 4 31 Justin Allgaier Brandt Chevrolet 250 40 118.8 34,225 Running 5 5 32 Kyle Larson # Cottonelle Chevrolet 250 40 1 110.8 29,650 Running 1 22 6 8 6 Trevor Bayne Ford EcoBoost Ford 250 38 103.9 26,800 Running 7 3 33 Ty Dillon (i) WESCO Chevrolet 250 0 100.2 26,035 Running 8 16 5 Kasey Kahne (i) Great Clips Chevrolet 250 0 98.0 19,895 Running 9 2 2 Brian Scott Husky Liners Chevrolet 250 35 96.0 25,650 Running 10 25 11 Elliott Sadler OneMain Financial Toyota 249 34 81.7 27,400 Running 11 21 43 Michael Annett Pilot Travel Centers/Jack Link's Ford 248 33 82.6 25,375 Running 12 13 12 Sam Hornish Jr Snap-On Ford 248 32 86.6 25,075 Running 13 11 60 Travis Pastrana Roush Fenway Racing Ford 248 31 80.9 24,975 Running 14 17 10 Cole Whitt Gold Bond/Carnegie Hotel Toyota 248 30 73.5 18,910 Running 15 20 21 Brendan Gaughan (i) South Point Chevrolet 248 0 67.9 20,040 Running 16 29 14 Jeff Green Hefty/Reynolds Toyota 248 28 61.7 24,830 Running -

A Comparative Look at Antitrust Law and NASCAR's Charter System, 28 Marq

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 28 Article 8 Issue 1 Fall Not Everyone Qualifies: A ompC arative Look at Antitrust Law and NASCAR's Charter System Tyler M. Helsel Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Tyler M. Helsel, Not Everyone Qualifies: A Comparative Look at Antitrust Law and NASCAR's Charter System, 28 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 235 (2017) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol28/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HELSEL 28.1 FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 12/18/17 3:30 PM NOT EVERYONE QUALIFIES: A COMPARATIVE LOOK AT ANTITRUST LAW AND NASCAR’S CHARTER SYSTEM TYLER M. HELSEL* I. INTRODUCTION The National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) has become the largest and most influential motor sports league in the world. Multi-million-dollar contracts for drivers, sponsors, and equipment make an investment into a team a huge financial risk. As a result, many teams are not created or created fairly. Most recently, Michael Waltrip Racing (MWR), which had committed sponsors and employees, was forced to shut down due to the economic costs of running a team.1 In response to this, teams formed the Race Team Alliance (RTA), a non-union association of team owners with a goal of getting more equity in individual teams.2 The RTA, in conjunction with NASCAR, formed a chartering system. -

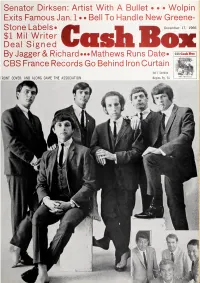

Deal Signed by Jagger& Richard •••Mathews Runs Date* CBS France Records Go Behind Iron Curtain

Senator Dirksen: Artist With A Bullet • • • Wolpin Exits Famous Jan. 1 • • Bell To Handle New Greene- Stone Labels* $1 Mil Writer Deal Signed By Jagger& Richard •••Mathews Runs Date* CBS France Records Go Behind Iron Curtain Int'l Section FRONT COVER: AND ALONG CAME THE ASSOCIATION Begins Pg. 55 p All the dimensions of a#l smash! *smm 1 4-439071 P&ul Revere am The THE single of '66 B THE SPIRIT OP *67 from this brand PAUL REVERE tiIe RAIDERS INCLUDING: HUNGRY THE GREAT AIRPLANE new album— STRIKE GOOD THING LOUISE 1001 ARABIAN NIGHTS CL2595/CS9395 (Stereo) Where the good things are. On COLUMBIA RECORDS ® "COLUMBIA ^MAPCAS REG PRINTED IN U SA GashBim Cash Bock Vol. XXVIII—Number 22 December 17, 1966 (Publication Office) 1780 Broadway New York, N. Y. 10019 (Phone: JUdson 6-2640) CABLE ADDRESS: CASHBOX, N. Y. JOE ORLECK Chairman of the Board GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher NORMAN ORLECK Executive Vice President MARTY OSTROW Vice President LEON SCHUSTER Disk Industry—1966 Treasurer IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL TOM McENTEE Associate Editor RICK BOLSOM ALLAN DALE EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI JERRY ORLECK BERNIE BLAKE The past few issues of Cash Box Speaking of deals, 1966 was marked Director Advertising of have told the major story of 1966. by a continuing merger of various in- ^CCOUNT EXECUTIVES While there were other developments dustry factors, not merely on a hori- STAN SO I PER BILL STUPER of considerable importance when the zontal level (label purchases of labels), Hollywood HARVEY GELLER, long-range view is taken into account, but vertical as well (ABC's purchase of ED ADLUM the record business is still a business a wholesaler, New Deal). -

NASCAR Sprint Cup Series - Atlanta Motor Speedway - 9/2/2012 Last Update: 8/27/2012 1:50:00 PM

53rd Annual ADVOCARE "500" - NASCAR Sprint Cup Series - Atlanta Motor Speedway - 9/2/2012 Last Update: 8/27/2012 1:50:00 PM Entry Veh # Driver Owner Crew Chief Veh Mfg Sponsor 1 1 Jamie McMurray Felix Sabates Kevin Manion 12 Chevrolet Bass Pro Shops 2 2 Brad Keselowski Roger Penske Paul Wolfe 12 Dodge Miller Lite 3 5 Kasey Kahne Linda Hendrick Kenny Francis 12 Chevrolet Hendrickcars.com 4 9 Marcos Ambrose Richard Petty Todd Parrott 12 Ford DeWALT 5 10 Danica Patrick(i) Tommy Baldwin Tommy Baldwin 12 Chevrolet GoDaddy Chevrolet 6 11 Denny Hamlin J D Gibbs Darian Grubb 12 Toyota Sport Clips 7 13 Casey Mears Bob Germain Bootie Barker III 12 Ford No. 13 GEICO Ford Fusion 8 14 Tony Stewart Margaret Haas Steve Addington 12 Chevrolet OFFICE DEPOT / MOBIL 1 9 15 Clint Bowyer Rob Kauffman Brian Pattie 12 Toyota 5-Hour Energy 10 16 Greg Biffle Jack Roush Matt Puccia 12 Ford 3M/Manheim Auctions 11 17 Matt Kenseth John Henry Jimmy Fennig 12 Ford Roush Fenway 25 Winning Years 12 18 Kyle Busch Joe Gibbs Dave Rogers 12 Toyota Wrigley 13 119 Mike Bliss(i) Randy Humphrey Skip Pope 11 Ford Plinker Tactical 14 20 Joey Logano Joe Gibbs Jason Ratcliff 12 Toyota The Home Depot 15 21 Trevor Bayne(i) Glen Wood Donnie Wingo 12 Ford Good Sam/Camping World 16 22 Sam Hornish Jr(i) Walter Czarnecki Todd Gordon 12 Dodge Shell Pennzoil 17 23 Scott Riggs Robert Richardson Sr Greg Conner 12 Chevrolet North Texas Pipe 18 24 Jeff Gordon Rick Hendrick Alan Gustafson 12 Chevrolet DuPont 19 26 Josh Wise Jerry Freeze Charles Dickey Jr 12 Ford MDS Transport 20 27 Paul Menard -

Declaration of Michael Curb

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE NASHVILLE DIVISION CURB RECORDS, INC. and MIKE CURB FOUNDATION, Plaintiffs, v. Civil Action No. 3:21-cv-0500 WILLIAM LEE, as Governor of the State of Tennessee, in his official capacity; CARTER LAWRENCE, as Commissioner of the Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance, in his official capacity; WILLIAM B. HERBERT IV, as Director of the Nashville Department of Codes and Building Safety, in his official capacity; and GLENN FUNK, as District Attorney General for the 20th Judicial District of Tennessee, in his official capacity, Defendants. DECLARATION OF MICHAEL CURB I, Michael Curb, do herby voluntarily make the following declaration under penalty of perjury: 1. I am over the age of 18 and fully competent to testify to the matters set forth in this declaration. I have personal knoWledge of the matters set forth herein. 2. I started my career in the record business almost six decades ago in California and Curb Records, Inc. (“Curb Records”) has operated for almost three decades in Nashville, Tennessee. I am fortunate that Curb Records has been very successful, launching the careers of numerous stars and my companies over the almost six decades have achieved more than 300 No. 1 records. Curb Records currently maintains its principal office in Nashville, Tennessee. Case 3:21-cv-00500 Document 12-1 Filed 07/01/21 Page 2 of 6 PageID #: 53 3. In addition to my Work as a record producer, I have personally written more than 400 songs and received BMI performance awards for compositions in the pop and country music genres. -

October 29, 1975 the White House Time Day Washington, D.C

Scanned from the President's Daily Diary Collection (Box 78) at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDENT GERALD R. FORD ;; PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo .• Day. Yr.) OCTOBER 29, 1975 THE WHITE HOUSE TIME DAY WASHINGTON, D.C. 7:50 a.m.WEDNESDA) '" -PHONE TIME 1l ;0 !:! ACTIVITY ;;: II<:" II II In Out "- II<: 7:50 The President,. had breakfast. 8:23 The President went to the Oval Office. 8:45 8:55 The President met with his Assistant, Donald H. Rumsfeld. 8:55 9:05 The President met with: '1...:\ Robert Gable, Republican candidate for Governor of Kentucky \-$~ '\ John T. Calkins, Executive Assistant to Counsellor Robert T. Hartmann F'~ Members of the press, in/out 9:10 P The President telephoned Congressman Charles A. Mosher (R Ohio). The call was not completed. The President met with: 9:10 9:40 Mr. Hartmann 9:10 9:40 Mr. Rumsfeld 9:20 9:40 L. William Seidman, Executive Director of the Economic Policy Board and Assistant for Economic Affairs 9:40 10:20 The President met with Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger. 10:30 10:40 The President met with: -.~'~' Philip W. Buchen, Counsel,' Edward C. Schmults, Deputy Counsel-designate Richard B. Cheney, Deputy Assistant 10:40 10:50 The President participated in the swearing-in ceremony for Mr. Schmults to be Deputy Counsel. For a list of attendees, see APPENDIX "A." 10:50 10:54 P The President talked with Congressman Mosher. 11:05 11:40 The President met with Associate Editor Robert Orben.